Chapter 19 Synthetic Mesh Choices for Surgical Repair

1 Introduction to Synthetic Mesh Materials

Modern herniorrhaphy relies on the use of prosthetic implants to allow for tension-free repairs of hernia defects. Such widespread use of mesh implants has greatly reduced the incidence of hernia recurrence. Surgeons continuously seek the ideal mesh—pliable and durable with chemical inertness and limited immunogenicity. Synthetic meshes have been used for over half a century, since Dr. Francis Usher popularized the use of polypropylene in the late 1950s. However, only recently have there been any changes in their original design. Current manufacturing techniques involve modifications of mesh polymers, reduction in fiber density, increase in pore size, and combinations of the above in attempts to create an “ideal mesh” to replace native fascia during hernia repair.

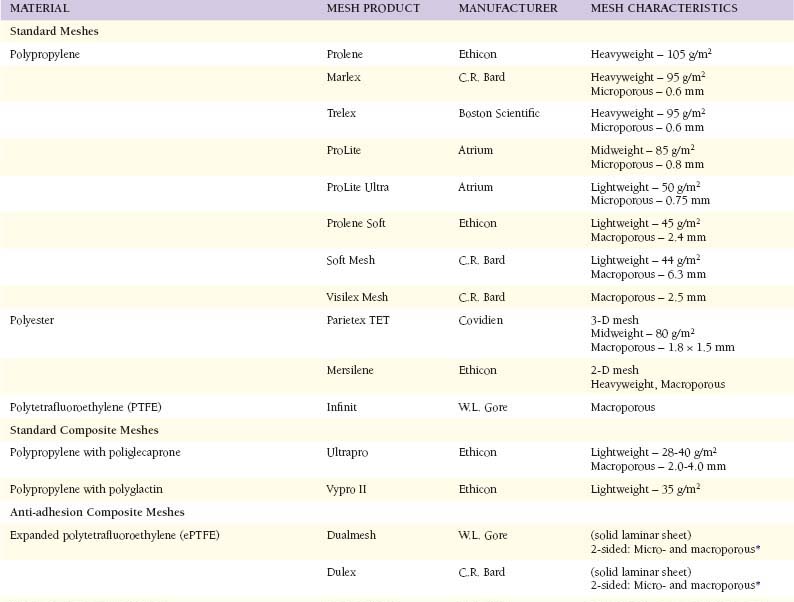

Modern herniorrhaphy relies on the use of prosthetic implants to allow for tension-free repairs of hernia defects. Such widespread use of mesh implants has greatly reduced the incidence of hernia recurrence. Surgeons continuously seek the ideal mesh—pliable and durable with chemical inertness and limited immunogenicity. Synthetic meshes have been used for over half a century, since Dr. Francis Usher popularized the use of polypropylene in the late 1950s. However, only recently have there been any changes in their original design. Current manufacturing techniques involve modifications of mesh polymers, reduction in fiber density, increase in pore size, and combinations of the above in attempts to create an “ideal mesh” to replace native fascia during hernia repair.2 Mesh Characteristics (Table 19-1)

1 Material

Polypropylene constitutes the most common polymer used in surgical meshes. It is highly durable and has been proved successful in hernia repairs for over 50 years. Because of unraveling at the edges when cut, current meshes are typically knitted instead of woven. While still popular because of its strength, durability, and pliability, polypropylene meshes are not without their drawbacks. Traditional polypropylene induces a strong inflammatory reaction upon implantation. Such inflammation can lead to excessive fibrosis, loss of pliability, and chronic pain. Additionally, when exposed to bowel, uncoated polypropylene may lead to extensive adhesions and/or fistulas.

Polypropylene constitutes the most common polymer used in surgical meshes. It is highly durable and has been proved successful in hernia repairs for over 50 years. Because of unraveling at the edges when cut, current meshes are typically knitted instead of woven. While still popular because of its strength, durability, and pliability, polypropylene meshes are not without their drawbacks. Traditional polypropylene induces a strong inflammatory reaction upon implantation. Such inflammation can lead to excessive fibrosis, loss of pliability, and chronic pain. Additionally, when exposed to bowel, uncoated polypropylene may lead to extensive adhesions and/or fistulas. Polyester is a hydrophilic polymer incorporated into meshes. It has been manufactured as a 2-dimensional (flat) sheet or a 3-dimensional sheet to allow for greater incorporation of host tissues. One of the advantages of polyester is its pliability, which allows the surgeon to easily manipulate and fixate the mesh to the conformations of the abdominopelvic walls. Polyester is unique in its hydrophilic nature; however, the clinical relevance of this feature remains unknown. Like polypropylene, unprotected polyester can lead to significant inflammatory reactions with ensuing fibrosis, adhesions, and fistulas.

Polyester is a hydrophilic polymer incorporated into meshes. It has been manufactured as a 2-dimensional (flat) sheet or a 3-dimensional sheet to allow for greater incorporation of host tissues. One of the advantages of polyester is its pliability, which allows the surgeon to easily manipulate and fixate the mesh to the conformations of the abdominopelvic walls. Polyester is unique in its hydrophilic nature; however, the clinical relevance of this feature remains unknown. Like polypropylene, unprotected polyester can lead to significant inflammatory reactions with ensuing fibrosis, adhesions, and fistulas. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is a carbon and fluorine-based synthetic hydrophobic polymer most commonly recognized in nonstick cookware (Teflon). Laminar or “expanded” polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) biomaterials for use in hernia repair (Dualmesh, W.L. Gore) were introduced in 1983. PTFE is a strong and relatively inert biomaterial; it is flexible and soft with resultant ease of handling of the mesh. Until recently, PTFE-based mesh has been manufactured as solid sheets of expanded PTFE with both microporous and macroporous (corrugated) surfaces to allow anti-adhesion and tissue ingrowth properties, respectively. Dualmesh also can be coated with a silver chlorhexadine layer (Dualmesh Plus, W.L. Gore) to impede mesh infectability.

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is a carbon and fluorine-based synthetic hydrophobic polymer most commonly recognized in nonstick cookware (Teflon). Laminar or “expanded” polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) biomaterials for use in hernia repair (Dualmesh, W.L. Gore) were introduced in 1983. PTFE is a strong and relatively inert biomaterial; it is flexible and soft with resultant ease of handling of the mesh. Until recently, PTFE-based mesh has been manufactured as solid sheets of expanded PTFE with both microporous and macroporous (corrugated) surfaces to allow anti-adhesion and tissue ingrowth properties, respectively. Dualmesh also can be coated with a silver chlorhexadine layer (Dualmesh Plus, W.L. Gore) to impede mesh infectability.2 Weight and Density

Studies have shown that traditional “heavyweight” meshes demonstrate four times the tensile and burst strength of the native abdominal wall. As a result, traditional meshes may be overengineered for use in most hernia repairs. The latest generation of meshes has been designed to reduce the amount of implanted prosthetic material. These so-called lightweight meshes are manufactured with thinner filaments and/or larger pore sizes resulting in markedly reduced mesh “weights,” measured in grams per m2. Such reduction (>50%) in prosthetic weight potentially allows for a reduced inflammatory reaction, more flexibility, and improved compliance, especially in the long-term.

Studies have shown that traditional “heavyweight” meshes demonstrate four times the tensile and burst strength of the native abdominal wall. As a result, traditional meshes may be overengineered for use in most hernia repairs. The latest generation of meshes has been designed to reduce the amount of implanted prosthetic material. These so-called lightweight meshes are manufactured with thinner filaments and/or larger pore sizes resulting in markedly reduced mesh “weights,” measured in grams per m2. Such reduction (>50%) in prosthetic weight potentially allows for a reduced inflammatory reaction, more flexibility, and improved compliance, especially in the long-term.3 Porosity

In addition to reducing fiber caliber and density, increasing the distance between the mesh fibers also contributes to overall foreign body reduction. Following implantation, each mesh fiber is surrounded by some degree of inflammation and fibrosis. Microporous mesh induces significant perifilamentous fibrosis that tends to blend together, creating a scar plate. As pore size is increased between fibers, less bridging fibrosis may be observed, with subsequent reduced scar plate formation. This results in improved fluid transport across the mesh, theoretically lessening seroma formation. Marlex is considered a microporous mesh, with a pore size of 0.6 mm. Ultrapro, one of the most macroporous meshes, contains pore sizes ranging from 2 to 4 mm (diagonal-shaped pores).

In addition to reducing fiber caliber and density, increasing the distance between the mesh fibers also contributes to overall foreign body reduction. Following implantation, each mesh fiber is surrounded by some degree of inflammation and fibrosis. Microporous mesh induces significant perifilamentous fibrosis that tends to blend together, creating a scar plate. As pore size is increased between fibers, less bridging fibrosis may be observed, with subsequent reduced scar plate formation. This results in improved fluid transport across the mesh, theoretically lessening seroma formation. Marlex is considered a microporous mesh, with a pore size of 0.6 mm. Ultrapro, one of the most macroporous meshes, contains pore sizes ranging from 2 to 4 mm (diagonal-shaped pores).4 Anti-adhesion Barrier

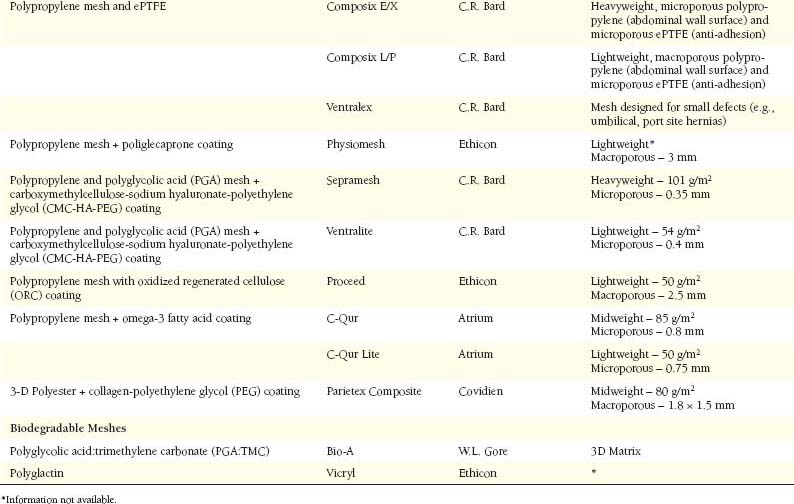

The advent of laparoscopic surgery necessitated development of so-called composite meshes. The principal benefit of these meshes is the ability to strategically place them intraperitoneally to impede adhesion formation on one side while promoting tissue ingrowth on the other side. While most intraperitoneal meshes incorporate two layers of materials, Dualmesh (W.L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) is manufactured by the fusion of two layers of ePTFE. A macroporous layer is corrugated and roughened to promote tissue ingrowth. This is paired with a microporous layer, which is best suited for the visceral surface by allowing for minimal and filmy adhesions. Accordingly, the smooth microporous layer is designed to face the peritoneal cavity and the rough macroporous side is to be placed against the abdominal wall to allow for tissue incorporation.

The advent of laparoscopic surgery necessitated development of so-called composite meshes. The principal benefit of these meshes is the ability to strategically place them intraperitoneally to impede adhesion formation on one side while promoting tissue ingrowth on the other side. While most intraperitoneal meshes incorporate two layers of materials, Dualmesh (W.L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) is manufactured by the fusion of two layers of ePTFE. A macroporous layer is corrugated and roughened to promote tissue ingrowth. This is paired with a microporous layer, which is best suited for the visceral surface by allowing for minimal and filmy adhesions. Accordingly, the smooth microporous layer is designed to face the peritoneal cavity and the rough macroporous side is to be placed against the abdominal wall to allow for tissue incorporation. The ability of ePTFE to resist adhesion formation is also used in Composix EX (C.R. Bard, Cranston, NJ, USA). This mesh type includes a smooth microporous layer of ePTFE under a layer of standard polypropylene. The smooth ePTFE surface is positioned toward the abdominal contents and serves as a protective interface against the bowel. The polypropylene side faces the abdominal wall to be incorporated into the native peritoneum and fascial tissue. Although it still remains popular, many surgeons have recently been reluctant to use this product because of fear of potential exposure of polypropylene to the abdominal viscera, stemming from technical errors at implantation or excessive shrinkage of the ePTFE layer, with resultant increase in adhesion formation and other serious intestinal complications.

The ability of ePTFE to resist adhesion formation is also used in Composix EX (C.R. Bard, Cranston, NJ, USA). This mesh type includes a smooth microporous layer of ePTFE under a layer of standard polypropylene. The smooth ePTFE surface is positioned toward the abdominal contents and serves as a protective interface against the bowel. The polypropylene side faces the abdominal wall to be incorporated into the native peritoneum and fascial tissue. Although it still remains popular, many surgeons have recently been reluctant to use this product because of fear of potential exposure of polypropylene to the abdominal viscera, stemming from technical errors at implantation or excessive shrinkage of the ePTFE layer, with resultant increase in adhesion formation and other serious intestinal complications. The layers of most other composite meshes consist of a synthetic material and an anti-adhesion polymer. The peritoneal layer (tissue ingrowth side) is composed of a typical polypropylene or polyester sheet. Visceral (nonadhesive) surfaces consist of various chemical polymer-based coatings. Today, such coatings include omega-3 fatty acids (C-Qur), poliglecaprone (Physiomesh), hyaluronic acid (Sepramesh), polyethylene glycol (Parietex), and oxidized regenerated cellulose (Proceed), among others. These coatings are intended to persist until neoperitoneum has covered the mesh, typically within 10 to 14 days after implantation. However, such absorbable adhesion barriers may be damaged by handling of the mesh during implantation, thus reducing its anti-adhesive properties.

The layers of most other composite meshes consist of a synthetic material and an anti-adhesion polymer. The peritoneal layer (tissue ingrowth side) is composed of a typical polypropylene or polyester sheet. Visceral (nonadhesive) surfaces consist of various chemical polymer-based coatings. Today, such coatings include omega-3 fatty acids (C-Qur), poliglecaprone (Physiomesh), hyaluronic acid (Sepramesh), polyethylene glycol (Parietex), and oxidized regenerated cellulose (Proceed), among others. These coatings are intended to persist until neoperitoneum has covered the mesh, typically within 10 to 14 days after implantation. However, such absorbable adhesion barriers may be damaged by handling of the mesh during implantation, thus reducing its anti-adhesive properties.5 Absorbable, Partially Absorbable, and Biodegradable Meshes

The aforementioned meshes are composed of permanent polymers; however, varieties of permanent meshes contain absorbable materials. The addition of absorbable fibers such as polyglactin (Vicryl, Ethicon, Inc) in Vypro composite meshes (Ethicon, Inc) or poliglecaprone (Monocryl, Ethicon, Inc) in Ultrapro adds stiffness to the composite mesh. This feature is particularly important for the lighter weight meshes to improve mesh handling during implantation, while reducing the overall foreign material within the patient after complete resorption of the extra fibers occurs.

The aforementioned meshes are composed of permanent polymers; however, varieties of permanent meshes contain absorbable materials. The addition of absorbable fibers such as polyglactin (Vicryl, Ethicon, Inc) in Vypro composite meshes (Ethicon, Inc) or poliglecaprone (Monocryl, Ethicon, Inc) in Ultrapro adds stiffness to the composite mesh. This feature is particularly important for the lighter weight meshes to improve mesh handling during implantation, while reducing the overall foreign material within the patient after complete resorption of the extra fibers occurs. Bio-A (W.L. Gore and Associates) represents the first biodegradable synthetic mesh sheet. Its intended function is more akin to a biologic mesh prosthetic than a typical knit synthetic mesh, as its biodegradable scaffold is gradually replaced by native collagen. Composed of polyglycolic acid and trimethylene carbonate (similar to a PDS suture material), it resorbs in approximately 3-6 months. Although this material has a proven record in staple/suture line reinforcement and hiatal repairs, its efficacy in reinforcement of tensile forces during abdominal wall reconstructions remains unclear.

Bio-A (W.L. Gore and Associates) represents the first biodegradable synthetic mesh sheet. Its intended function is more akin to a biologic mesh prosthetic than a typical knit synthetic mesh, as its biodegradable scaffold is gradually replaced by native collagen. Composed of polyglycolic acid and trimethylene carbonate (similar to a PDS suture material), it resorbs in approximately 3-6 months. Although this material has a proven record in staple/suture line reinforcement and hiatal repairs, its efficacy in reinforcement of tensile forces during abdominal wall reconstructions remains unclear.3 Clinical Implications of Biomaterials

1 Material Type:

Polyester, polypropylene, and PTFE remain the three most common synthetic substrates used for mesh. Although tissue reactions of biomaterials vary greatly in the literature, our recent experience in rodent experiments demonstrated that the polyester-based mesh was the greatest inducer of inflammation and appeared to impose a severe chronic foreign body reaction. While the polypropylene meshes displayed significant inflammation and some foreign body reaction, the severity was strikingly less when compared to polyester. Compared to the knit meshes in our study, integration of the laminar ePTFE mesh within tissues was met more with heavy fibrosis and encapsulation instead of integration. This has been seen in other in vivo studies and clinically, with excised samples of previously implanted ePTFE demonstrating significant fibrosis. In addition, decreased neovascularization seen in our study may have further predisposed ePTFE mesh to a diminished biocompatibility. Heavy fibrosis and encapsulation may lead to mesh shrinkage. Overall, we found polypropylene to exhibit the highest degree of tissue biocompatibility followed by ePTFE and, finally, polyester. The clinical implications of these findings are not entirely clear, and no randomized controlled trials have evaluated these materials in a comparative fashion.

Polyester, polypropylene, and PTFE remain the three most common synthetic substrates used for mesh. Although tissue reactions of biomaterials vary greatly in the literature, our recent experience in rodent experiments demonstrated that the polyester-based mesh was the greatest inducer of inflammation and appeared to impose a severe chronic foreign body reaction. While the polypropylene meshes displayed significant inflammation and some foreign body reaction, the severity was strikingly less when compared to polyester. Compared to the knit meshes in our study, integration of the laminar ePTFE mesh within tissues was met more with heavy fibrosis and encapsulation instead of integration. This has been seen in other in vivo studies and clinically, with excised samples of previously implanted ePTFE demonstrating significant fibrosis. In addition, decreased neovascularization seen in our study may have further predisposed ePTFE mesh to a diminished biocompatibility. Heavy fibrosis and encapsulation may lead to mesh shrinkage. Overall, we found polypropylene to exhibit the highest degree of tissue biocompatibility followed by ePTFE and, finally, polyester. The clinical implications of these findings are not entirely clear, and no randomized controlled trials have evaluated these materials in a comparative fashion.2 Material Weight

Most prosthetics, although chemically inert, generate an intense host inflammatory reaction. The host response to implanted prosthetic biomaterials follows a cascading sequence of events (coagulation, inflammation, angiogenesis, epithelialization, fibroplasia, matrix deposition, and contraction) with a resultant formation of dense connective tissue at the site of implantation. Although this may have an important positive role in mesh incorporation, the increased amount of connective tissue does not necessarily translate to strength and durability of the hernia repair. A rigid scar plate resulting from pronounced perifilamentous fibrosis and deposition of collagen fibers contributes to the loss of prosthetic pliability. In the long-term, such acquired stiffness of mesh products contributes to the changes in compliance of both the hernia site and the whole abdominal wall. Clinically, this decrease in compliance can lead to a sensation of stiffness and result in both physical discomfort and significant limitations in the activities of daily living in many patients. The deleterious foreign body effects of synthetic meshes have been linked to the amount of foreign body implanted. As a result, a goal of modern mesh manufacturers has been the development of prosthetic implants that are able to meet the tensile demands of the abdominal wall while limiting the foreign body burden at the site of the repair. Similar to our previous experience, as well as that of other investigators, our laboratory recently confirmed that lightweight and midweight polypropylene mesh displayed a marked reduction in fibrosis and foreign body reaction when compared to the heavyweight polypropylene. Beyond doubt, reduction of the overall “weight” of the mesh implant is associated with a significant increase in biocompatibility of the prosthetic.

Most prosthetics, although chemically inert, generate an intense host inflammatory reaction. The host response to implanted prosthetic biomaterials follows a cascading sequence of events (coagulation, inflammation, angiogenesis, epithelialization, fibroplasia, matrix deposition, and contraction) with a resultant formation of dense connective tissue at the site of implantation. Although this may have an important positive role in mesh incorporation, the increased amount of connective tissue does not necessarily translate to strength and durability of the hernia repair. A rigid scar plate resulting from pronounced perifilamentous fibrosis and deposition of collagen fibers contributes to the loss of prosthetic pliability. In the long-term, such acquired stiffness of mesh products contributes to the changes in compliance of both the hernia site and the whole abdominal wall. Clinically, this decrease in compliance can lead to a sensation of stiffness and result in both physical discomfort and significant limitations in the activities of daily living in many patients. The deleterious foreign body effects of synthetic meshes have been linked to the amount of foreign body implanted. As a result, a goal of modern mesh manufacturers has been the development of prosthetic implants that are able to meet the tensile demands of the abdominal wall while limiting the foreign body burden at the site of the repair. Similar to our previous experience, as well as that of other investigators, our laboratory recently confirmed that lightweight and midweight polypropylene mesh displayed a marked reduction in fibrosis and foreign body reaction when compared to the heavyweight polypropylene. Beyond doubt, reduction of the overall “weight” of the mesh implant is associated with a significant increase in biocompatibility of the prosthetic. The clinical evidence for the benefits of this theoretical improvement is evolving. In a recent randomized trial of inguinal herniorrhaphies, the use of lightweight mesh reduced the foreign body sensation to less than half of that reported with standard densely woven polypropylene mesh. In addition, physically active patients reported significantly less pain on exercise. In another series of hernia patients, a reduction of paresthesia from 58% in the heavyweight group to 4% in the lightweight group was noted. More recently, the most compelling evidence for the benefits of lightweight mesh to date was published. In a double-blinded, prospective series of hernia patients with bilateral inguinal defects, both traditional and lightweight meshes were implanted with each patient being their own control. One hundred percent of patients were able to point out correctly the side with a lightweight mesh. The patients reported overall significant decrease in mesh sensation and pain at the site of implantation. Overall, it appears that the implantation of lightweight polypropylene mesh results in decreased chronic discomfort and reduced restriction of physical activities while providing more than adequate strength for the reinforcement of hernia repairs. It is important to point out, however, that the use of lightweight meshes as a “bridge” should probably be avoided as it may lead to excessive bulging and, rarely, central mesh failures. Therefore, we have adopted a policy of highly selective use of lightweight products. For laparoscopic ventral hernia repairs without defect closure, for rare cases of “bridging” of defects during open ventral herniorrhaphies, and during laparoscopic repairs of moderate to large direct inguinal hernias, we advocate the use of midweight or traditional meshes to ensure a durable repair.

The clinical evidence for the benefits of this theoretical improvement is evolving. In a recent randomized trial of inguinal herniorrhaphies, the use of lightweight mesh reduced the foreign body sensation to less than half of that reported with standard densely woven polypropylene mesh. In addition, physically active patients reported significantly less pain on exercise. In another series of hernia patients, a reduction of paresthesia from 58% in the heavyweight group to 4% in the lightweight group was noted. More recently, the most compelling evidence for the benefits of lightweight mesh to date was published. In a double-blinded, prospective series of hernia patients with bilateral inguinal defects, both traditional and lightweight meshes were implanted with each patient being their own control. One hundred percent of patients were able to point out correctly the side with a lightweight mesh. The patients reported overall significant decrease in mesh sensation and pain at the site of implantation. Overall, it appears that the implantation of lightweight polypropylene mesh results in decreased chronic discomfort and reduced restriction of physical activities while providing more than adequate strength for the reinforcement of hernia repairs. It is important to point out, however, that the use of lightweight meshes as a “bridge” should probably be avoided as it may lead to excessive bulging and, rarely, central mesh failures. Therefore, we have adopted a policy of highly selective use of lightweight products. For laparoscopic ventral hernia repairs without defect closure, for rare cases of “bridging” of defects during open ventral herniorrhaphies, and during laparoscopic repairs of moderate to large direct inguinal hernias, we advocate the use of midweight or traditional meshes to ensure a durable repair.3 Microporous vs. Macroporous mesh:

Although the significance of mesh porosity has been suggested, until recently we found limited objective evidence linking pore size to biocompatibility. It does appear, however, that a great deal of importance lies with the fibrotic reactions that take place between the mesh fibers or fiber bundles. With smaller mesh pores, the fibrosis that surrounds each mesh fiber bridges with the fibrosis of adjacent mesh fibers. We found that macroporous meshes contain a “neutral zone” between mesh fibers free of any foreign body and resultant decrease in host inflammatory response and fibrosis. In fact, when comparing three different polypropylene meshes, we found that biocompatibility was clearly proportional to the pore size of the mesh. Additionally, the large pore “neutral zones” allow for local tissue ingrowth while reducing chronic inflammation across the entire mesh.

Although the significance of mesh porosity has been suggested, until recently we found limited objective evidence linking pore size to biocompatibility. It does appear, however, that a great deal of importance lies with the fibrotic reactions that take place between the mesh fibers or fiber bundles. With smaller mesh pores, the fibrosis that surrounds each mesh fiber bridges with the fibrosis of adjacent mesh fibers. We found that macroporous meshes contain a “neutral zone” between mesh fibers free of any foreign body and resultant decrease in host inflammatory response and fibrosis. In fact, when comparing three different polypropylene meshes, we found that biocompatibility was clearly proportional to the pore size of the mesh. Additionally, the large pore “neutral zones” allow for local tissue ingrowth while reducing chronic inflammation across the entire mesh. Macroporous meshes appear to also demonstrate increased ability to resist infection. Recent European studies demonstrated safe use of macroporous meshes in clean-contaminated and even contaminated fields. Rapid mesh incorporation is likely a key contributor to these observations of decreased mesh infection. Additionally, larger pores may improve fluid transport across the mesh due to a decrease in flow resistance. This, in turn, leads to more efficient fluid removal, as well as nutrient and oxygen transport, possibly leading to a reduction in postoperative seromas and faster healing. Overall, there are markedly improved tissue reactions, decreased fibrosis, and likely decreased infectability in meshes with larger pore sizes.

Macroporous meshes appear to also demonstrate increased ability to resist infection. Recent European studies demonstrated safe use of macroporous meshes in clean-contaminated and even contaminated fields. Rapid mesh incorporation is likely a key contributor to these observations of decreased mesh infection. Additionally, larger pores may improve fluid transport across the mesh due to a decrease in flow resistance. This, in turn, leads to more efficient fluid removal, as well as nutrient and oxygen transport, possibly leading to a reduction in postoperative seromas and faster healing. Overall, there are markedly improved tissue reactions, decreased fibrosis, and likely decreased infectability in meshes with larger pore sizes.4 Other Considerations

1 Anisotropy

The material properties of meshes contribute to the overall mechanical behavior of the repair of hernia defects. While the differing elasticity of meshes when pulled in different directions (i.e. anisotropy) has not been well defined to date, ongoing studies show that many commonly used meshes have up to 20-fold differences in their stretchability when pulled in perpendicular directions. This may factor into the success of abdominal wall repairs, as the native abdominal wall is roughly twice as elastic in the vertical (craniocaudal) axis versus the horizontal axis. As a result, mesh implantation may need to be strategic in order to address the differences in both the textile properties of the prosthetic and the physiologic properties of the abdominal wall. However, proper mesh marking to guide surgeons in properly orienting mesh during implantation is lacking (nor is it required) in nearly all products on the market today.

The material properties of meshes contribute to the overall mechanical behavior of the repair of hernia defects. While the differing elasticity of meshes when pulled in different directions (i.e. anisotropy) has not been well defined to date, ongoing studies show that many commonly used meshes have up to 20-fold differences in their stretchability when pulled in perpendicular directions. This may factor into the success of abdominal wall repairs, as the native abdominal wall is roughly twice as elastic in the vertical (craniocaudal) axis versus the horizontal axis. As a result, mesh implantation may need to be strategic in order to address the differences in both the textile properties of the prosthetic and the physiologic properties of the abdominal wall. However, proper mesh marking to guide surgeons in properly orienting mesh during implantation is lacking (nor is it required) in nearly all products on the market today.2 Pre-shaped mesh

In an effort to accommodate abdominopelvic contours during repair, preformed meshes are available. These meshes are typically used in inguinal repairs and assist surgeons to laparoscopically place a mesh over the myopectineal orifice without the buckling effect that may occur when using a flat piece of mesh. In addition, preformed plugs may be used to “occlude” an indirect inguinal defect. Clear-cut clinical benefits of preshaped meshes have not been established to date.

In an effort to accommodate abdominopelvic contours during repair, preformed meshes are available. These meshes are typically used in inguinal repairs and assist surgeons to laparoscopically place a mesh over the myopectineal orifice without the buckling effect that may occur when using a flat piece of mesh. In addition, preformed plugs may be used to “occlude” an indirect inguinal defect. Clear-cut clinical benefits of preshaped meshes have not been established to date.Cobb W.S., Kercher K.W., Heniford B.T. The argument for lightweight polypropylene mesh in hernia repair. Surg Innov. 2005;12:63-69.

Junge K., Klinge U., Rosch R., Klosterhalfen B., Schumpelick V. Functional and morphologic properties of a modified mesh for inguinal hernia repair. World J Surg. 2002;26:1472-1480.

Lichtenstein I.L., Shulman A.G., Amid P.K., Montllor M.M. The tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg. 1989;157:188-193.

Nilsson E., Haapaniemi S., Gruber G., Sandblom G. Methods of repair and risk for reoperation in Swedish hernia surgery from 1992 to 1996. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1686-1691.

Novitsky Y.W., Harrell A.G., Hope W.W., Kercher K.W., Heniford B.T. Meshes in hernia repair. Surg Technol Int. 2007;16:123-127.

Saberski E.R., Orenstein S.B., Novitsky Y.W. Anisotropic evaluation of synthetic surgical meshes. Hernia. 2011;15(1):47-52.

Usher F.C., Ochsner J., Tuttle L.L.Jr. Use of marlex mesh in the repair of incisional hernias. Am Surg. 1958;24:969-974.