CHAPTER 98

Coccydynia

Ariana Vora, MD; Amy X. Yin, MD

Definition

Coccydynia is pain in the vicinity of the coccygeal bone at the base of the spine. It may be localized to the lower sacrum, the coccyx, or the adjacent muscles or soft tissues. Pain can be insidious or sudden in onset. Symptoms are usually triggered by sitting or rising from a sitting position.

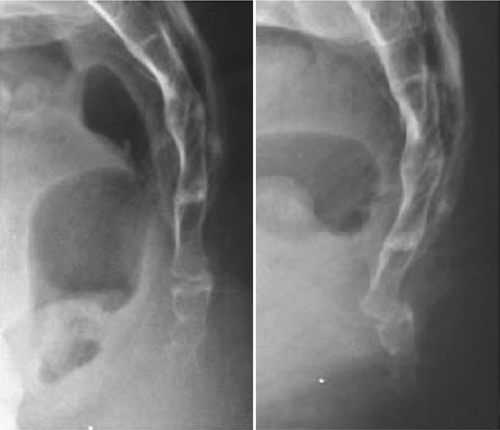

The mean age at onset of coccydynia is 40 years, but it can occur over a wide range of ages [1]. The most common inciting factor is trauma to the coccyx or surrounding soft tissue from a vertical axial blow or cumulative trauma from a difficult vaginal delivery. Pathologic features may range from dislocated sacrococcygeal fracture to ligamentous damage of the caudal coccygeal segments. In most cases, the tip of the coccyx is subluxated or hypermobile [1] (Figs. 98.1 and 98.2).

The coccyx consists of three to five rudimentary vertebrae. The first coccygeal segment has transverse processes that articulate and occasionally fuse with the sacrum. This vertebra is usually separate from the remaining coccygeal vertebrae, which may partially or completely fuse, leading to anatomic variation of one to four total bony coccygeal segments [2].

The fibrous sacrococcygeal symphysis connects the sacrum to these segments of the coccyx. This joint is reinforced by sacrococcygeal ligaments, which enclose the final intervertebral foramen through which the S5 roots exit. The S4, S5, and coccygeal roots contribute to the coccygeal plexus, which provides rich somatic and autonomic innervation to the anus, perineum, and genitals [3]. The levator ani (innervated by S3-S5 nerve root branches through perineal and inferior rectal nerve branches of the pudendal nerve [4]) and coccygeal muscles (innervated by S3-S5 nerve root branches [5]) attach to and support the coccyx during defecation and childbirth. The gluteus maximus also attaches to the lateral coccyx and can contribute to a sensation of pressure while sitting.

Morphology of the coccyx may have a role in coccydynia. The coccyx that is markedly curved or angled forward, is anteriorly subluxed [2], or contains a bone spicule [6] is more prone to pain. Degeneration of disc structures [7] and referred pain from lumbar disc disease [2] have been implicated. There are also reported cases of rare coccydynia pathologic processes, including tuberculosis, tumors, and calcification of the joints or tendons. Prevalence of coccydynia is four to five times higher in women than in men [8,9]. In addition to obstetric trauma [10], the increased susceptibility to injury in women is attributed to anatomy as the female coccyx is more posterior in location and larger than the male coccyx [11]. Coccydynia is three times more frequent in obese women than in nonobese women [6], and this may be related to decreased pelvic rotation while sitting.

Symptoms

Coccygeal pain is located at the tip or sides of the coccyx. The quality of pain is usually dull and achy at baseline and intermittently sharp during activities that aggravate the symptoms. A sensation of pressure or an urge to defecate is also commonly described. Coccydynia has been associated with dyspareunia, dyschezia, dysmenorrhea, and piriformis syndrome. Symptoms are usually exacerbated by sitting on hard surfaces, prolonged sitting, and moving from the sitting to the standing position. Symptoms are generally relieved by taking weight off the coccyx.

Levator ani syndrome and proctalgia fugax are variants of coccydynia.

Levator ani syndrome is a dull ache or pressure sensation in the rectum, with pain episodes lasting more than 20 minutes at a time. Symptoms tend to be more severe during the day than at night. Symptoms may result from a hypertonic levator ani or puborectalis muscle or from inflammation of the arcus tendon of the levator ani [12,13]. This syndrome is associated with posterior traction of the puborectalis muscle and levator ani muscle tenderness on rectal examination.

Proctalgia fugax is the sudden onset of excruciating anal pain lasting a few seconds or minutes, then disappearing completely. Proctalgia fugax is characterized by spastic muscle contractions of the pelvic floor [14]. Episodes usually occur fewer than five times a year [15]. Symptoms are not typically related to defecation but are associated with sexual intercourse. Symptoms are usually nocturnal and awaken the patient from sleep. Unlike coccydynia, which is more common in women, proctalgia fugax occurs equally in men and women.

Physical Examination

• Palpate the pelvic area for evidence of lymphadenopathy or pelvic masses to rule out neoplastic or infectious disease (see the section on differential diagnosis).

• Assess for point tenderness or palpable abnormalities along the pelvic girdle, including the tip of the coccyx where a spicule would be located. It is also important to palpate surrounding joints. Classic findings in coccydynia are exquisite tenderness to direct palpation of the coccyx, sacrococcygeal ligaments, and pubococcygeal ligaments.

• Evaluate leg lengths, pelvic obliquity, sacroiliac motion, and sacroiliac joint tenderness because correction of these problems may be part of the treatment.

Lower extremity strength, reflexes, and sensation should be assessed for focal neurologic deficits and should be normal in coccydynia.

Digital rectal examination should include testing for occult blood, palpation for internal masses, and palpation of the levator ani muscles for tenderness. Manipulation of the coccygeal tip, the pubococcygeal ligament, and the sacrococcygeal joint should be performed to assess for tenderness and hypermobility [16].

Functional Limitations

Because coccydynia is often worsened by sitting, driving can become very painful. Sedentary work involving prolonged sitting may exacerbate symptoms; frequent breaks may be required. It is common to avoid social situations because of pain when sitting. Because of pressure to the coccyx and muscle contractions in the perineum during orgasm, sexual intimacy can worsen symptoms and is often avoided. Equestrian activities, cycling, and contact sports can also be particularly painful.

Diagnostic Studies

Coccydynia is often associated with subluxation or hypermobility of the tip of the coccyx (Fig. 98.3), which is usually seen on dynamic radiographs [1,17]. Single-position radiographs are seldom helpful in differentiating morphologic differences. Dynamic lateral radiographs are obtained in lateral and oblique views while the patient is sitting and standing. These demonstrate pelvis rotation and coccygeal mobility and may show fusion of the sacrococcygeal joint and superior intercoccygeal joints [1,17].

Bone scans and magnetic resonance imaging may show inflammation, fracture, or bone fragments. Because they are static tests, they are no more useful than dynamic radiographs in the diagnosis of hypermobility or subluxation [1]. However, advanced imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging may be useful as second-line imaging to detect pericoccygeal inflammatory reactions, bone signal changes and edema, disc changes, or coccygeal tumors [18]. This may be clinically informative and guide treatment when dynamic radiographs are unremarkable.

Anal manometry testing has been described in the literature, with conflicting reports on its utility. The basis for manometry testing is the theory that prolonged sphincter contraction or dystonia may contribute to coccygeal pain. Abnormal anal manometric pressures support a diagnosis of proctalgia fugax, but the test is unlikely to diagnose proctalgia fugax because episodes are so infrequent. Anal manometry is not routinely recommended in the evaluation of coccydynia.

Treatment

Initial

Conservative treatment is the “gold standard” for coccydynia as the natural history does not usually lead to deterioration. Medication management includes topical perianal lidocaine cream or gel, a bowel regimen or laxatives, acetaminophen, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Although they are relatively safe interventions, the efficacy of sitz baths, muscle relaxants, anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressants, acupuncture, iontophoresis, biofeedback, and electrogalvanic stimulation has not been established in the literature.

Rehabilitation

Ergonomic adaptation is commonly recommended. A trial of a doughnut-shaped pillow is always worthwhile to offload weight on the coccyx while sitting. Lifestyle recommendations, such as refraining from cycling, equestrian sports, or contact sports, may be beneficial.

Physical therapy should include pelvic massage and manipulation, pelvic relaxation techniques, pelvic floor strengthening exercises, pelvic joint mobilization, and postural correction. In patients with proctalgia fugax and levator ani symptoms, emphasis is placed on pelvic floor relaxation techniques. Correction of leg length discrepancy can help with referred sacroiliac pain. Psychological support is also crucial.

Procedures

Injection of the sacrococcygeal ligament and coccyx tip with 1% lidocaine can be diagnostic. A mixture of steroid (40 mg methylprednisone) and a long-acting anesthetic (0.25% bupivacaine) may be used for therapeutic purposes [19]. This procedure can be done with use of physical landmarks. Ultrasound-guided injection can be considered but has not been well documented. Fluoroscopic guidance has been used, but utility may be limited as visualization of ligaments is not possible.

If there is dislocation of the coccyx, manipulation under anesthesia may be helpful, but there are no conclusive data on the efficacy of this approach.

Botulinum toxin injection of the puborectalis and pubococcygeus muscles may relieve pain associated with muscle hypertonicity [20,21].

Prolotherapy is an injection of proliferant solution that may relieve the pain of enthesopathy and facilitate regeneration of torn or painful sacrococcygeal and pubococcygeal ligaments. Its safety is well established. Although there are no randomized studies, a prospective observational study using dextrose prolotherapy for recalcitrant coccydynia indicated relief in 30 of 37 patients [22].

More recently, there has been some reported success with interventional procedures, such as ganglion impar nerve block or radiofrequency ablation. The ganglion impar (also known as ganglion of Walther) is a solitary structure in the precoccygeal space at the caudal end of the sympathetic chain implicated in nociceptive and sympathetic supply to the perineum. Various techniques including transcoccygeal and extracoccygeal approaches under fluoroscopy, ultrasonography, or computed tomography guidance have demonstrated pain relief in small prospective studies of patients with chronic perineal pain or coccydynia [23,24].

Pulsed radiofrequency has also been investigated for coccydynia. A prospective trial of 21 patients with coccydynia refractory to conservative management showed excellent to good results in 81% of patients [25].

These procedures may be considered possible alternatives to surgery.

Surgery

Most people recover with conservative treatment alone within weeks to months. A number of uncontrolled studies of patients with refractory coccydynia report pain relief with partial and total coccygectomy [1,26–30]. Successful treatment is usually associated with abnormal coccygeal motion.

Potential Disease Complications

Coccydynia is a symptom and not a disease. The primary complication is functional decline secondary to local pain, generally limiting sitting tolerance, sexual intercourse, and exercise tolerance.

Potential Treatment Complications

Gastrointestinal, hepatic, and renal complications may arise from prolonged use of acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Steroid injections may also be complicated by skin depigmentation and transient elevation in blood glucose level. Repeated steroid injections may result in ligamentous breakdown and altered mobility in the sacrococcygeal ligament. All procedures, including injections, nerve blocks, pulsed radiofrequency, and surgery, may result in infections. Coccygectomy complications also include bleeding or hematoma, delayed wound healing, and wound dehiscence [9].