Cervical Tongs or Halo Ring: Application for Use in Cervical Traction (Assist)

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge of neuroanatomy and physiology is necessary.

• The nurse needs to be knowledgeable about the anatomy and physiology of the spinal column, the special anatomy of the cervical vertebrae, the spinal cord, the cervical spinal nerves, and their areas of peripheral innervation. In addition, it is important that the nurse understands the pathophysiology and manifestations of spinal cord trauma, including ascending edema, spinal shock and related impairment of respiratory function, vasomotor tone, and autonomic nervous system function.

• It is essential that the nurse understands the pathophysiology of spinal cord injury, including the concepts of primary versus secondary spinal cord injury and spinal shock.

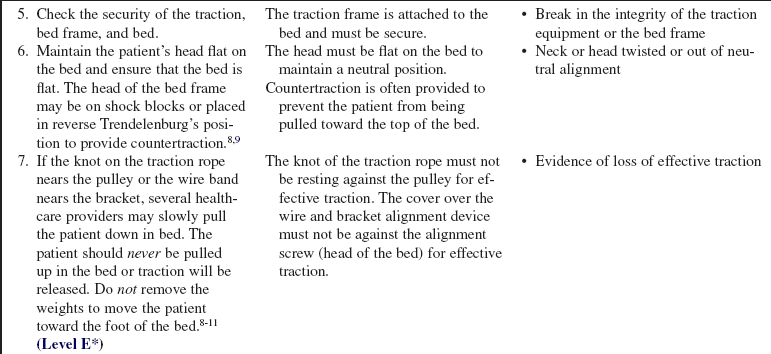

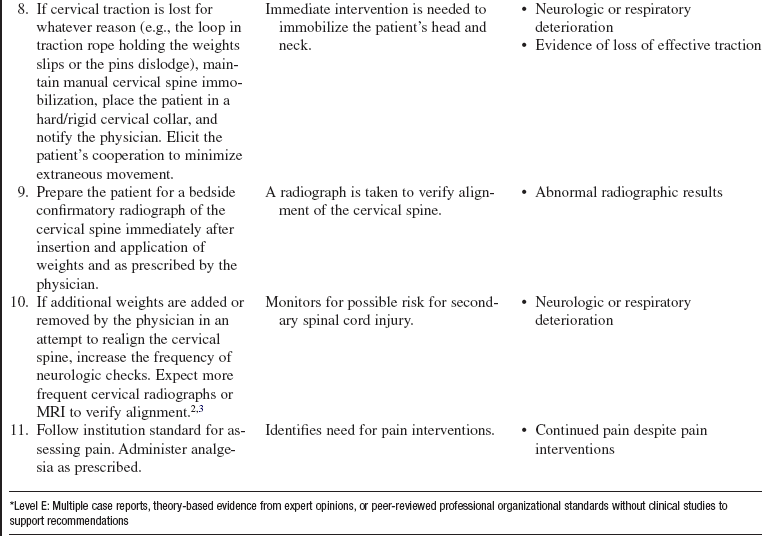

• The nurse needs to be knowledgeable about the signs and symptoms of new spinal cord injury or extension of injury, for example, impairment or increased impairment of motor function and sensation, respiratory function, and autonomic nervous system function resulting in loss of vasomotor tone.

• The nurse should be able to state appropriate interventions that may be necessary if new or increased spinal cord injury occurs.

• A number of treatment options are available to manage cervical injuries. The specific treatment for a particular patient depends on the type of injury, the level of injury (e.g., C2 as compared with C6), the specific classification of the injury, and patient characteristics.

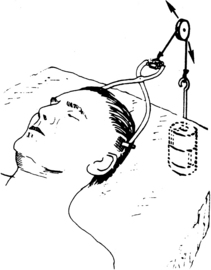

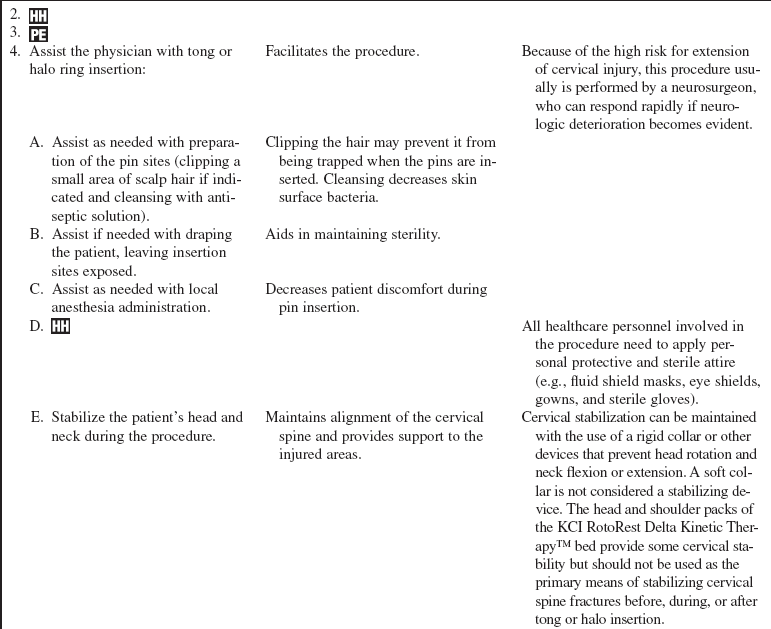

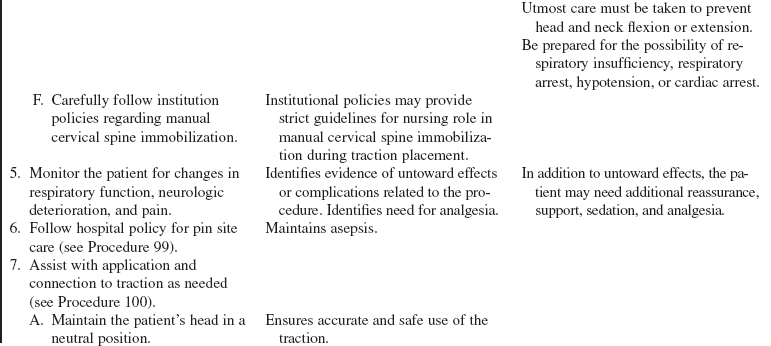

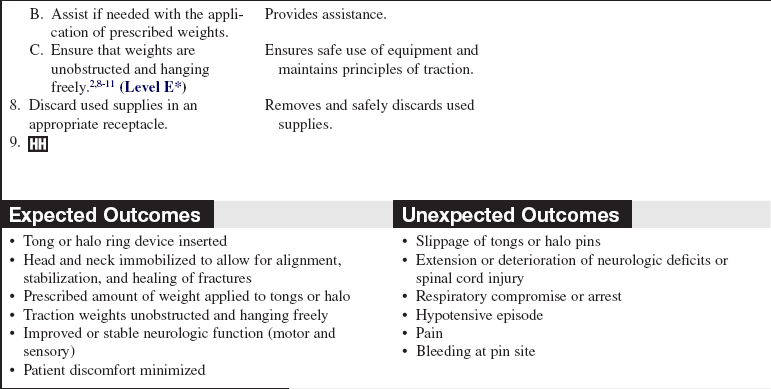

• Cervical spine traction is provided to realign, immobilize, and stabilize the cervical spine when it has become unstable as a result of a cervical spine fracture or dislocation caused by trauma or disease, degenerative processes of the cervical vertebrae, or spinal surgery (Fig. 97-1).3,4 After initial medical stabilization of the patient and assessment and documentation of neurologic function, cervical skeletal traction with the tongs or halo ring can be applied to realign the cervical spine. Tongs or a halo ring may be used with cervical traction to reduce dislocation before the patient undergoes surgery. Occasionally, an unstable cervical spinal injury may necessitate long-term cervical traction for a period of weeks to attain realignment and immobilization to stabilize the spine. The definitive method used to treat cervical fractures depends on the injury classification and physician or institution preference.

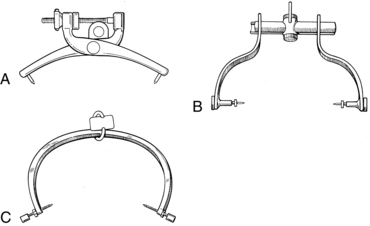

• Tongs consist of a body with one pin attached at each end (Fig. 97-2). Tong pins are applied to the outer table of the skull on both sides of the skull. Cervical tongs are available in a variety of types, such as Crutchfield, Gardner-Wells, and Vinke tongs.

• The shape, features, insertion site, and placement vary slightly, but the purpose, principles, and care are the same. Physician preference is an important deciding factor in choosing the specific device to be used.2,11

• The insertion of Crutchfield and Vinke tongs necessitates an incision to expose the skull. Two holes are made in the outer table of the skull with a twist drill, and the pins are inserted and tightened until there is a firm fit.2,11

• Gardner-Wells tongs are inserted by placing the razor-sharp pin edges to the prepared areas of the scalp and tightening the screws until the spring-loaded mechanism indicates that the correct pressure has been achieved. To decrease the possibility of tong displacement, all types of pins are well seated into the outer table of the skull and angled inward.2,6,11

• Tongs are made of stainless steel or a graphite body with titanium pins. The graphite body with titanium pins is compatible with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

• Traction can be applied with the use of a rope and pulley system or a cable and alignment bracket. Weights are added gradually and followed with radiographic imaging. The physician uses serial radiographs of the cervical spine to assist in determining the optimal amount of traction (measured in pounds) needed to reduce a fracture and provide optimal alignment. Excessive traction may result in stretching of the spinal cord and subsequent damage.2–4 The addition of traction is managed by the physician.

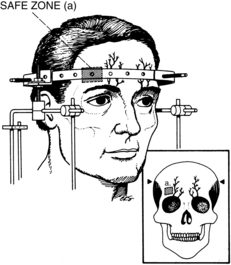

• Cervical traction also may be applied with a halo ring device. This is a stainless steel or graphite ring that is attached to the skull by four stabilizing pins (two anterior and two posterolateral; Fig. 97-3). Skull pins can be made of stainless steel, titanium, or ceramic material.1,2,5,7 Pins are threaded through holes in the ring, screwed into the outer table of the skull, and locked into place. Traction can be applied to the ring device with the use of a rope and pulley system or a cable and bracket alignment system. Weights are added gradually. After alignment of the cervical spine is achieved, the spine can be immobilized by attaching the ring to a body vest or a custom molded body jacket. The patient then is able to move while the head and neck remain immobile.

EQUIPMENT

• Insertion tray, including either the specific type of tongs to be used or the halo ring with insertion pins

• Local anesthetic: lidocaine, 1% to 2% (with or without epinephrine, depending on physician preference)

• Sterile and nonsterile gloves

• Gowns, masks, and eye shields

• Antiseptic solution (e.g., 2% chlorhexidine-based preparation)

• Sterile drill and bits (for insertion of Crutchfield and Vinke tongs)

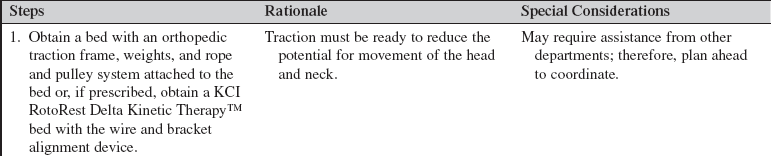

• Rope and traction assembly for the bed (If a KCI RotoRest Delta Kinetic Therapy™ bed is used, a cable and bracket alignment system is needed; see Procedure 100.)

• S and C hooks (to attach to the distal end of the rope for weight application)

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure and the reason for cervical traction. Clarify or reinforce information as needed by the patient or family. Discuss use of any special equipment, such as a special bed, that may be needed.  Rationale: Patient and family anxiety is decreased.

Rationale: Patient and family anxiety is decreased.

• Explain the patient’s role in assisting with insertion of the tongs.  Rationale: Explanation elicits patient cooperation and facilitates insertion.

Rationale: Explanation elicits patient cooperation and facilitates insertion.

• Explain that the procedure can be uncomfortable when the incisions are made but that an anesthetic will be administered by the physician.  Rationale: This information prepares the patient for what to expect.

Rationale: This information prepares the patient for what to expect.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

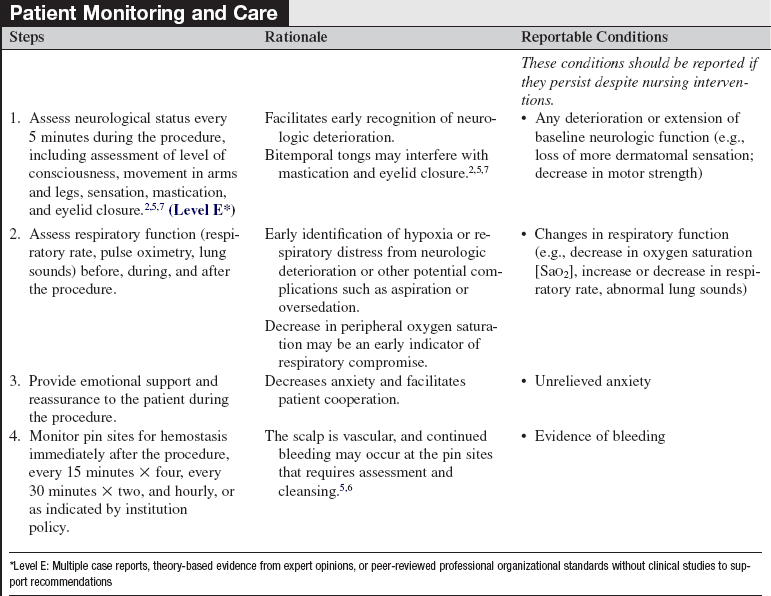

• Conduct a complete neurologic assessment that includes evaluation of cranial nerve function, motor strength of major muscles, sensation (assessment of light touch, pain, and proprioception, noting highest dermatome level), and deep tendon reflexes (biceps, triceps, patella, and Achilles) and superficial reflexes (abdominal and anal wink).  Rationale: Baseline data are provided for comparison of postinsertion assessments to determine the presence of neurologic compromise or extension of spinal cord injury.

Rationale: Baseline data are provided for comparison of postinsertion assessments to determine the presence of neurologic compromise or extension of spinal cord injury.

• Assess the patient’s vital signs.  Rationale: Baseline data are provided for comparison with assessments after insertion.

Rationale: Baseline data are provided for comparison with assessments after insertion.

• Assess the patient’s respiratory pattern and auscultate lung sounds. Note the use of accessory respiratory muscles and any signs or symptoms of dyspnea.  Rationale: Baseline data are established to determine any compromise to respiratory function as a result of the procedure.

Rationale: Baseline data are established to determine any compromise to respiratory function as a result of the procedure.

• Inspect the scalp for abrasions, lacerations, or sites of infection.  Rationale: Any potential sites of infection that may contraindicate the insertion of a cervical fixation device into the infected area are identified.

Rationale: Any potential sites of infection that may contraindicate the insertion of a cervical fixation device into the infected area are identified.

• Assess the level of pain or discomfort and anxiety.  Rationale: Assessment establishes data for decision making regarding the need for analgesia or anxiolytics for comfort and cooperation during the insertion procedure.

Rationale: Assessment establishes data for decision making regarding the need for analgesia or anxiolytics for comfort and cooperation during the insertion procedure.

• Assess for any allergies to an antiseptic agent, local anesthetic or analgesia and anxiolytics.  Rationale: Review of medication allergies before administration of a new medication decreases the chances of an allergic reaction.

Rationale: Review of medication allergies before administration of a new medication decreases the chances of an allergic reaction.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that informed consent has been obtained.  Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Ensure that the head of the bed is flat and that the patient’s head is in a neutral position by whatever approved means (e.g., hard/rigid collar) have been instituted.  Rationale: This measure prevents mobilization of neck, which may increase the risk of injury or extension of spinal cord injury.

Rationale: This measure prevents mobilization of neck, which may increase the risk of injury or extension of spinal cord injury.

References

1. Bono, CM. The halo fixator. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007; 15:728–737.

2. Canale, ST, Beaty, JH. Cervical spine injuries. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. ed 11. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2008:1776–1777. [[electronic resource]].

![]() 3. Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Initial closed reduction of cervical spine fracture-dislocation injuries. Neurosurgery. 2002; 50(Suppl 3):S44–S50.

3. Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Initial closed reduction of cervical spine fracture-dislocation injuries. Neurosurgery. 2002; 50(Suppl 3):S44–S50.

![]() 4. Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Treatment of -subaxial cervical spine injuries. Neurosurgery. 2002; 50(Suppl 3):S156–S165.

4. Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Treatment of -subaxial cervical spine injuries. Neurosurgery. 2002; 50(Suppl 3):S156–S165.

![]() 5. Hayes, VM, Silber, JS, Siddiqu, FN, et al. Complications -of halo fixation of the cervical spine. Am J Orthop. 2005; 34:271–276.

5. Hayes, VM, Silber, JS, Siddiqu, FN, et al. Complications -of halo fixation of the cervical spine. Am J Orthop. 2005; 34:271–276.

6. Hickey, JV. Vertebral and spinal cord injuries. In: Hickey JV, ed. The clinical practice of neurological and neurosurgical nursing. ed 6. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:410–453.

![]() 7. Kang, M, Vives, MJ, Vaccaro, AR, The halo vest. principles of application and management of complications. J Spinal Cord Med 2003; 26:186–192.

7. Kang, M, Vives, MJ, Vaccaro, AR, The halo vest. principles of application and management of complications. J Spinal Cord Med 2003; 26:186–192.

![]() 8. Osmond, T. Principles of traction. Aust Nurs J. 1999; 6:1–4. [(Suppl)].

8. Osmond, T. Principles of traction. Aust Nurs J. 1999; 6:1–4. [(Suppl)].

![]() 9. Styrcula, L, Traction basics. part I. Orthop Nurs. 1994; 13(2):71–74.

9. Styrcula, L, Traction basics. part I. Orthop Nurs. 1994; 13(2):71–74.

![]() 10. Styrcula, L, Traction basics. part II. Orthop Nurs. 1994; 13(3):55–59.

10. Styrcula, L, Traction basics. part II. Orthop Nurs. 1994; 13(3):55–59.

![]() 11. Styrcula, L, Traction basics. part III. Orthop Nurs. 1994; 13(4):34–44.

11. Styrcula, L, Traction basics. part III. Orthop Nurs. 1994; 13(4):34–44.

![]() Davis, A. Sensory and motor disorders. In: Kinney MR, et al, eds. AACN clinical reference for critical care nursing. ed 4. St Louis: Mosby; 1998:711.

Davis, A. Sensory and motor disorders. In: Kinney MR, et al, eds. AACN clinical reference for critical care nursing. ed 4. St Louis: Mosby; 1998:711.

![]() Jerome Cervical Spine System. Application instructions for Jerome Halo Traction Systems. Morristown, NJ: Jerome Cervical Spine System; 2003.

Jerome Cervical Spine System. Application instructions for Jerome Halo Traction Systems. Morristown, NJ: Jerome Cervical Spine System; 2003.

![]() Lee, TT, Green, BA. Advances in the management of acute spinal cord injury. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002; 33:311–315.

Lee, TT, Green, BA. Advances in the management of acute spinal cord injury. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002; 33:311–315.

![]() Maher, AB, Salmond, SW, Pellino, TA, Orthopedic nursing. ed 3. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2002:296.

Maher, AB, Salmond, SW, Pellino, TA, Orthopedic nursing. ed 3. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2002:296.

![]() McCloskey JC, Bulechek GM, eds.. Iowa Intervention Project. nursing interventions classification (NIC). ed 3. Mosby, St Louis, 2000.

McCloskey JC, Bulechek GM, eds.. Iowa Intervention Project. nursing interventions classification (NIC). ed 3. Mosby, St Louis, 2000.

![]() Mollabashy, A, Immobilization techniques in cervical spine injury. cervical orthoses, skeletal traction, and halo devices. Top Emerg Med 1997; 19:3.

Mollabashy, A, Immobilization techniques in cervical spine injury. cervical orthoses, skeletal traction, and halo devices. Top Emerg Med 1997; 19:3.