CHAPTER 95

Arachnoiditis

Michael D. Osborne, MD; Adam Wallace, MD

Definition

The meninges are a system of three protective membranes that surround the central nervous system and consist of the pia mater, arachnoid mater, and dura mater layers. Arachnoiditis is the development of chronic inflammation and progressive fibrosis of the arachnoid and pia layers of the meninges. It can occur subsequent to a variety of conditions, although it is most commonly a sequela of spinal surgery or the result of intrathecal injection of radiographic dyes and chemicals with neurotoxic preservatives [1]. Some of the etiologic factors linked to the development of arachnoiditis are listed in Table 95.1. Because arachnoiditis is rare, specific incidence and prevalence are uncertain.

When microtrauma to the vasculature of the arachnoid membrane and pia mater occurs, it can impair the normal mechanisms for control of excessive meningeal fibrosis [1]. This may result in the deposition of fibrous collagen bands in the arachnoid-pia membranes and cause the nerve roots to adhere to each other as well as to the dural sac. The pathophysiologic mechanism of arachnoiditis involves a progression from root inflammation (radiculitis) to root adherence (fibrosis). In severe cases, the arachnoid fibrosis can cause compressive root ischemia, and progressive neurologic deficits may ensue [2]. When this condition occurs in the meninges of the cervical and thoracic regions, the spinal cord can become enmeshed and constricted as well. Pain is the result of dural adherence with nerve root traction and nerve ischemia. Typically, arachnoiditis develops slowly during the period of months after the initial insult, although it may continue to develop for years, resulting in worsening pain and paresthesias or progressive neurologic injury [1].

Symptoms

The symptoms associated with arachnoiditis are heterogeneous and often difficult to distinguish from other disease processes, such as radiculopathy, spinal stenosis, cauda equina syndrome, and neuropathies. Also, because arachnoiditis is often acquired iatrogenically during the course of evaluation and treatment of spinal disorders, patients often have concomitant symptoms of mechanical back pain or myofascial pain in addition to the arachnoiditis symptom complex.

Patients with arachnoiditis principally report burning pain or paresthesias. However, these symptoms often do not follow typical radicular patterns. Pain is usually constant but exacerbated by movement. Some patients experience secondary muscle spasms. Weakness and muscle atrophy may also occur, and bowel or bladder sphincter dysfunction is not uncommon. Onset is insidious, and symptoms may first be manifested years after the inciting event [3]. Symptoms can range from mild (such as slight tingling of the extremities) to severe (such as excruciating pain with progressive neurologic deterioration). The condition may also be asymptomatic and discovered only incidentally on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Physical Examination

Neurologic examination typically reveals a patchy distribution of lower motor neuron deficits. Examination findings may include loss of reflexes, muscle weakness, muscle atrophy, anesthesia, gait instability, and reduced rectal tone [2]. Less commonly, arachnoiditis may involve the spinal cord; in these instances, upper motor neuron findings (hyperreflexia, spasticity, presence of Babinski response) can be found on examination.

A complete neurologic examination should be performed at the time of initial diagnosis. In the event that symptoms worsen, this examination may then be used as a benchmark to ascertain whether neurologic deterioration is occurring. In the setting of progressive neurologic decline, it is incumbent on the treating physician to rule out other pathologic processes (such as a new disc herniation) before neurologic deterioration is attributed solely to progressive arachnoid fibrosis.

Functional Limitations

Patients with arachnoiditis may exhibit a variety of functional limitations, the degree of which corresponds to the extent of the neurologic impairments and the severity of the pain. Gait instability, reduced ambulatory capacity, and impairment in activities of daily living are not uncommon. As time goes by, patients tend to suffer secondary effects of immobilization and deconditioning, causing further functional impairment. The severe pain and impaired mobility tend to isolate patients socially and to limit their ability to work. Because the pain associated with arachnoiditis is usually present even at rest, sedentary work or light duty does not always improve a patient’s symptoms enough to facilitate employment despite activity restrictions.

Diagnostic Studies

Presently, the diagnosis of arachnoiditis is most often made through the use of MRI. Historically, myelography was used routinely for diagnosis of arachnoiditis; characteristic findings included the observance of prominent nerve roots as well as various patterns of filling defects. The advent of computed tomography and MRI has made diagnosis easier.

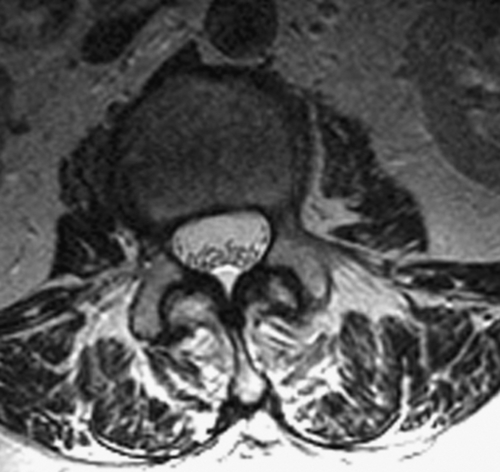

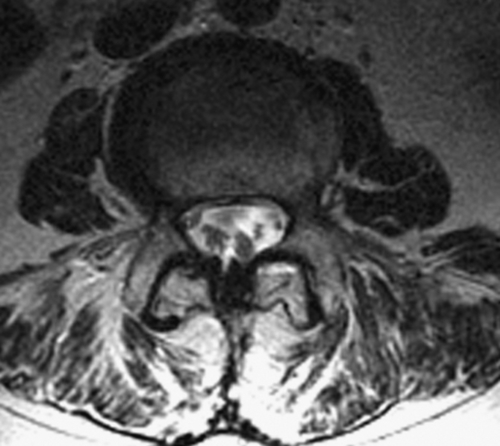

MRI is preferred to computed tomographic myelography because of its noninvasive nature. Typical findings include adherent roots located centrally in the thecal sac (considered mild arachnoiditis), an “empty sac” (where roots are adherent to the wall of the thecal sac), and a mass of soft tissue replacing the subarachnoid space (severe disease) [4]. These findings are well seen on T2-weighted axial images (Figs. 95.1 and 95.2). Although the administration of contrast material with MRI may help rule out other diseases in the differential diagnosis, such as tumors and infection, contrast enhancement is not necessary to visualize the characteristic appearance of arachnoiditis [5].

The diagnosis can also be made by computed tomographic myelography; even myelography with conventional radiography may be used if spinal instrumentation from prior fusion surgery creates too much artifact on MRI and computed tomography. The water-soluble myelographic contrast media used today (such as iohexol) are much safer than the prior oil-based media (Pantopaque), and serious adverse reactions involving the central nervous system are extremely rare (< 0.1%) [6]. There have not been any documented cases of adhesive arachnoiditis with the use of iohexol myelography [6].

Treatment

Initial

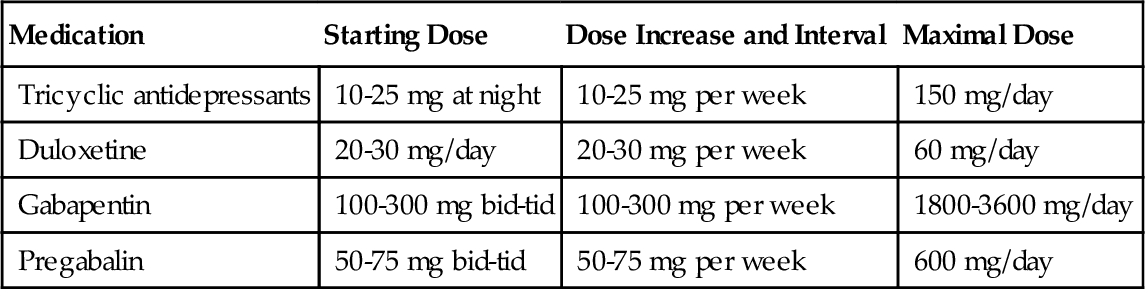

The treatment of arachnoiditis is palliative, and medications are often used for this purpose. Antidepressant or anticonvulsant analgesics are considered the mainstay of medical management, although other classes of medications may provide benefit as well. Many antidepressants and anticonvulsants have been used for years off-label for the treatment of neuropathic pain with reasonable efficacy. The tricyclic antidepressants (such as amitriptyline) are the most common. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has more recently approved several newer medications for use in specific neuropathic pain syndromes: duloxetine and pregabalin for diabetic neuropathy, and gabapentin and pregabalin for postherpetic neuralgia. These medications are often tried in patients with arachnoiditis with varying efficacy. Antidepressant and anticonvulsant analgesics are typically started at relatively low doses and titrated upward as tolerated. The precise starting dose and eventual maximal dose usually depend on how well the medication’s side effects are tolerated. Some examples of dosing regimens are listed in Table 95.2. For most of these medications, it often takes a few weeks at any given dose for optimal analgesic effect to be reached.

Anti-inflammatory medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) are commonly used as well with modest efficacy. This is probably because of the frequent occurrence of back pain in these patients. Often, patients with arachnoiditis have concomitant lumbar disc degeneration or osteoarthritis of the facet joints that may respond in part to anti-inflammatory medications. Likewise, patients with back pain may benefit from trials of muscle relaxants or more potent inhibitors of muscle contractions (antispasticity agents), such as baclofen and tizanidine. Baclofen has also been used off-label for treatment of neuropathic pain.

Opiates are often prescribed with varying degrees of success. In general, neuropathic pain seems to be less responsive to opiates. Some advocate the use of methadone because of its N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist activity, which may make it more effective for neuropathic pain syndromes. One of the chief limitations of opiates is the tendency for development of tolerance, requiring dose escalation.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation interventions can be divided into modalities for pain management and therapeutic exercise to improve pain as well as to aid function. Modalities such as heat application (superficial and deep) and ice application are most effective for treatment of the associated mechanical back pain and myofascial pain that often accompany arachnoiditis. Contrast baths can be used for distal extremity pain and can be helpful when the patient exhibits signs of peripheral sympathetic dysfunction. Electrical stimulation is primarily used to treat neuropathic pain, but it may also improve associated musculoskeletal and myofascial pain. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation can be applied at the paraspinal level or along the course of a peripheral nerve to help attenuate neuropathic pain.

Unfortunately, exercise typically offers the patient very little as a direct means of symptom improvement for severe neuropathic pain; yet exercise is still an important part of treatment. As previously mentioned, patients with arachnoiditis may suffer from other musculoskeletal pain, and therapeutic exercise (such as stretching, strength training, and aerobic exercise) often improves these associated disorders in this subset of patients as well as in those with chronic pain [7,8]. Patients with intractable pain often avoid activity because of increased pain or fear of pain provocation. As such, they often become deconditioned and benefit from gentle progressive exercise regimens. Aquatic therapy is generally well tolerated and can be used as a method to improve many of the manifestations of deconditioning and prolonged immobility, such as to improve joint motion, flexibility, aerobic capacity, and muscle strength.

Procedures

There are few data to support the role of neuraxial corticosteroid injections, such as epidural steroids and nerve root blocks, in arachnoiditis treatment. Anecdotally, short-duration improvement may be observed, and any such procedures are usually performed as a “do and see” proposition.

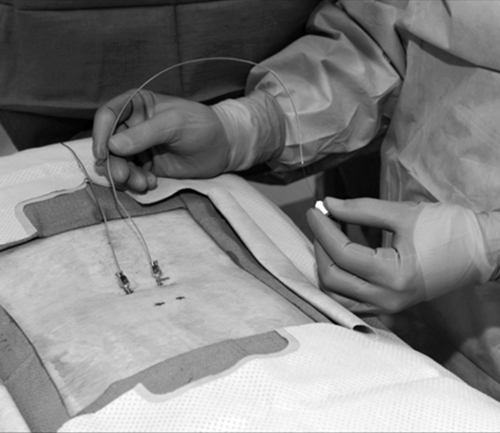

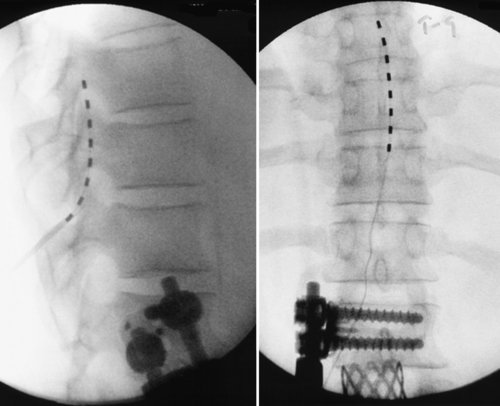

The most promising intervention for the intractable pain associated with arachnoiditis is spinal cord stimulation. Spinal cord stimulation, also known as dorsal column stimulation, involves the placement of a stimulating electrode (either percutaneously or through a laminotomy) over the dorsal aspect of the spinal cord (Figs. 95.3 and 95.4). Exact level and location of electrode placement depend on the location of the patient’s pain. Typically, patients undergo a percutaneous trial to test the stimulator’s efficacy before permanent implantation. The goal is to stimulate the spinal cord with low levels of electrical impulses that produce a nonpainful paresthesia that modulates (masks) the patient’s pain.

The largest studies investigating spinal cord stimulation have included patients with varied diagnoses, the most abundant of which is failed back surgery syndrome. It has been estimated that 11% of patients with failed back surgery syndrome have arachnoiditis. Approximately 50% to 60% of patients with failed back surgery syndrome treated with spinal cord stimulation receive more than 50% relief of their symptoms [9,10]. Studies investigating spinal cord stimulation efficacy in patients with a more specific diagnosis of epidural fibrosis or intradural fibrosis (arachnoiditis) have also found improvement in pain (60%), reduction of pain medication requirements (40%), and increased work capacity (25%) [11,12]. Spinal cord stimulation seems to be more effective for pain of neuropathic character than for pain of mechanical or musculoskeletal character. In addition, extremity pain is generally more easily treated compared with back pain–predominant symptoms [12].

Another option that could be considered is an intrathecal drug delivery system, which has been shown to be beneficial for those with chronic pain, whether it is neuropathic, nociceptive, or visceral in nature [13]. Medications such as opioids, local anesthetics, α-adrenergic receptor agonists, and NMDA receptor antagonists have all been successfully used. Recent use of intrathecal ziconotide has gained popularity for chronic neuropathic pain conditions. With all these interventions, one must consider the safety of the proposed treatment, taking special consideration of the risk of placing any intrathecal medication into an already pathologic spinal canal [13].

Surgery

There is very little role for surgical intervention in the treatment of arachnoiditis. There is no method of successfully surgically untangling the adherent nerve roots, although attempts have been made [14]. Indications for surgery include rapidly progressive neurologic deterioration, such as myelopathy due to progressive syringomyelia or cauda equina syndrome from arachnoiditis ossificans. In these instances, surgical intervention (shunt placement or removal of the calcific mass) could be contemplated. The emphasis on such interventions is to halt or to retard further neurologic deterioration. The prospect that such procedures will improve pain remains speculative at best. There has been some documentation of subarachnoidal endoscopy (thecaloscopy) to perform adhesiolysis, but long-term benefit has not been established [15].

Potential Disease Complications

In severe cases of arachnoiditis, the fibrous bands that cause adherence of the nerve roots may become so prolific that progressive nerve root injury (radiculopathy, polyradiculopathy) or spinal cord injury (cauda equina syndrome, myelopathy) can ensue. Constriction of the spinal cord vasculature causes ischemia and focal areas of spinal cord demyelination. This vascular ischemia and associated alterations of normal cerebrospinal fluid flow have been observed to result in the formation of arachnoid cysts, syringomyelia, and even communicating hydrocephalus [16,17]. Calcification of the fibrotic milieu results in a condition termed arachnoiditis ossificans, which may result in progressive nerve root or spinal cord compression [18].

Potential Treatment Complications

Medication side effects are common. Anticonvulsant and antidepressant analgesics often produce sedation or alteration of mental status. Opiates, too, can produce sedation as well as severe constipation. Opiate dependence is generally anticipated as a ramification of use of this class of medication long term. Although true psychological addiction to opiates can occur, it is much less common than one might expect. The propensity for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to cause gastrointestinal side effects is well known, as is their potential to adversely affect the kidneys and liver as well as to exacerbate hypertension and asthma.

Rehabilitation interventions are generally safe, although patients can suffer thermal injury from inappropriate application of superficial modalities. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation are generally considered contraindicated in patients with pacemakers. Therapeutic exercise may potentially exacerbate pain symptoms.

Spinal cord stimulation poses some risk; however, complications are usually minor, and the incidence of new neurologic injury from something such as bleeding, infection, or neural trauma is quite small [10]. The most frequent complication usually entails electromechanical failure, such as percutaneous lead migration, when the stimulation no longer covers the symptomatic body region. The majority of electromechanical complications can be remedied with revision of the system.