CASE 95

History: A 60-year-old woman presents with 6 hours of abdominal pain. History includes bowel resection for angiodysplasia and more recent laparotomy for division of adhesions.

1. Which of the following should be included in the differential diagnosis of the imaging finding shown in Figure A? (Choose all that apply.)

2. What is the origin of the gas in dilated bowel in a patient with obstruction?

C. Outgassing of dissolved gases

D. By-product of digestion of food

3. Strangulation is closed-loop obstruction with intestinal ischemia. Which finding on CT is most diagnostic of this complication?

4. What is the optimal modality for investigating acute small bowel dilatation?

ANSWERS

CASE 95

Dilated Small Bowel

1. A, B, and C

2. A

3. D

4. D

References

Maglinte DD, Kelvin FM, Rowe MG, et al: Small bowel obstruction: optimizing radiologic investigation and nonsurgical management. Radiology. 2001;218:39–46.

Cross-Reference

Gastrointestinal Imaging: THE REQUISITES, 3rd ed, p 106.

Comment

One of the problems most commonly evaluated by the radiologist (and surgeon) is dilated loops of small bowel. This evaluation is particularly difficult in the patient who develops distention after a surgical procedure. The main differential diagnostic concern is whether a true mechanical obstruction has developed or whether the bowel dilation is secondary to an adynamic ileus.

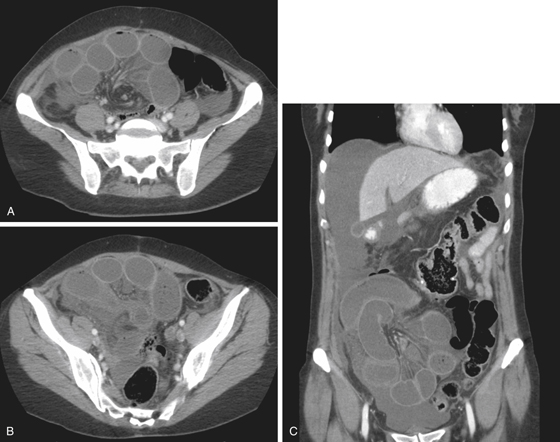

Most mechanical obstructions occur as the result of fibrous adhesions, which develop within days after surgery. However, mechanical obstruction within the first few days after abdominal surgery is quite rare. Usually it takes months or years before obstructions from adhesions become symptomatic (if they become symptomatic). When they are symptomatic, most are treated successfully with nasogastric decompression. The CT images in this case show high-grade small bowel obstruction (see figures). At surgery, a closed-loop obstruction of the distal and terminal ileum was found, including a 20-cm segment of ischemic nonviable bowel.

In the postoperative patient, the radiologist should be wary of diagnosing a mechanical obstruction when the colon is dilated up to the level of the anatomic splenic flexure (the point where the descending colon passes behind the phrenicocolic ligament and becomes retroperitoneal). Spasm at that site is relatively common in patients immediately following abdominal surgery, and the radiologist should consider this before deciding it is a mechanical obstruction.

Other causes of grossly dilated small bowel include hernias, either in the abdominal wall or internally. Fibrous bands also can lead to volvulus or closed-loop obstructions. For decades, contrast examination of the small bowel, along with plain film radiography, had been the standard for evaluation of the patient with suspected obstruction. Enteroclysis has been shown to be of somewhat greater benefit but is impractical for the postoperative patient. Today the use of CT has become standard. This modality can assess the site of obstruction and possible underlying causes of the problem. It is as sensitive as the other modalities and can be quite specific for determining the cause of the problem and identifying complications, which is most helpful for clinicians.