CHAPTER 94

Tibial Neuropathy (Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome)

Definition

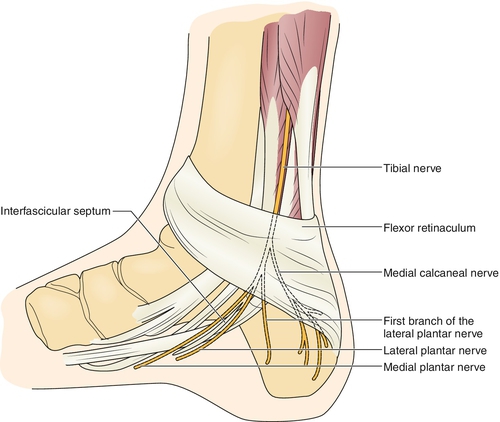

Tarsal tunnel syndrome can be described as a constellation of signs and symptoms caused by entrapment or compression of the tibial nerve or any of its branches within the tarsal tunnel, the region beneath the flexor retinaculum on the medial aspect of the ankle (Fig. 94.1). The tibial nerve branches that may be involved deep to the tarsal tunnel include the medial plantar nerve, lateral plantar nerve, Baxter nerve (also known as the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve or inferior calcaneal nerve), and medial calcaneal nerve [1]. Anatomically, the tarsal tunnel is a fibro-osseous structure that begins just posterior to the medial malleolus; the roof is the flexor retinaculum (also called the laciniate ligament), and the floor is formed by the tendons of the posterior tibialis, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus muscles. The tibial nerve usually divides into three branches at the level of the ankle: the medial plantar nerve, the lateral plantar nerve, and the medial calcaneal nerve. However, Baxter nerve (i.e., first branch of the lateral plantar nerve) usually branches from the lateral plantar nerve (but can branch off the tibial nerve) just distal to the origin of the medial calcaneal nerve at the level of the tarsal tunnel [2,3]. Baxter nerve then traverses laterally across the anterior aspect of the heel and terminates with motor branches to the abductor digiti quinti (or minimi) pedis muscle [2]. It is likely that tarsal tunnel syndrome occurs infrequently compared with other well-known focal entrapment neuropathies, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, and peroneal (fibular) neuropathy at the knee. In fact, in a retrospective review of isolated tibial neuropathies in the foot, the incidence of Baxter neuropathy (17%) was much greater than that of tarsal tunnel syndrome (5%) [4].

There are generally considered to be five basic categories that account for the etiology of tarsal tunnel syndrome: trauma and post-traumatic changes, mass or space-occupying lesions causing compression, systemic diseases, biomechanical causes related to joint structure or deformity, and idiopathic causes. In addition, the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism of tarsal tunnel syndrome remains elusive; a portion of the literature supports the process of demyelination, whereas other sources implicate axonal degeneration as the primary process [5,6]. It is thought that the tibial nerve may be entrapped proximally within the tarsal tunnel, or one of its branches (e.g., the medial plantar nerve) may be entrapped distally in its own calcaneal chamber [1]. Entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (i.e., Baxter nerve) has also been described as a cause of heel pain [7–10]. Therefore in a case of clinically suspected tarsal tunnel syndrome, the tibial nerve and its major terminal branches (including the medial plantar nerve, lateral plantar nerve, and Baxter nerve) should be thoroughly evaluated [4].

In the current literature, there is no mention of an age or gender preference in patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome. One possible explanation for this is the relatively low incidence and various causes of tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Symptoms

The patient usually presents with pain or paresthesias along with numbness over the sole of the foot [1,11]. Pain is typically described as burning or a dull ache, but it may also be expressed as throbbing, cramping, or even tightness, and pain may extend proximally to the medial calf. Symptoms are often exacerbated by prolonged standing or walking and may be worse at night but may not be well localized. However, if the distribution of sensory disturbance is limited to a particular region of the foot, these symptoms could correspond to a specific tibial nerve branch that is involved (e.g., medial sole of foot due to medial plantar nerve involvement). Obvious weakness of the intrinsic foot muscles is an uncommon patient complaint and may be manifested only if the resulting foot deformity is grossly noticeable or so severe that it causes an unstable gait pattern. Patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome generally present with unilateral symptoms.

Physical Examination

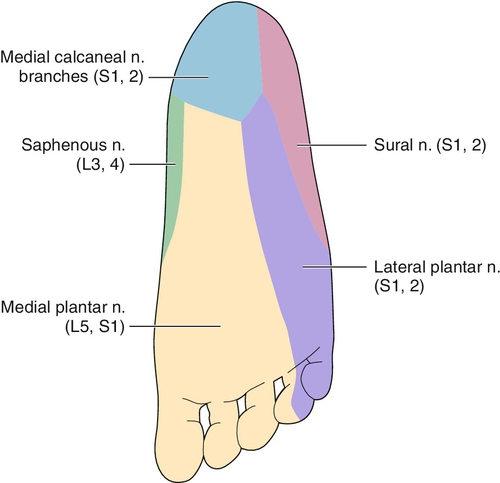

Sensory examination of a patient with tarsal tunnel syndrome should reveal decreased light touch or pinprick over the plantar aspect of the foot corresponding to the distribution of one or all of the tibial nerve branches involved (Fig. 94.2). Motor examination of the intrinsic foot muscles is challenging because it is often difficult for patients to selectively activate these muscles. However, one may be able to appreciate muscle atrophy of the involved foot because its appearance may be asymmetric compared with the other foot [1]. A patient with tarsal tunnel syndrome often has a Tinel sign over the tibial nerve or one of its branches in the tarsal tunnel (Fig. 94.3). On occasion, percussion over the tibial nerve at the ankle will elicit pain extending proximally along the course of the tibial nerve; this sign is called the Valleix phenomenon. There may also be palpable tenderness over the tibial nerve in the tarsal tunnel. Two other provocative maneuvers that may reproduce symptoms in the foot or ankle are extension of the great toe and sustained passive eversion of the ankle [1]. Muscle stretch reflexes in the lower extremity (including patellar, medial hamstring, and Achilles) should be normal and symmetric compared with the unaffected side. Peripheral pulses (posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis) are usually palpable and unremarkable. If the biomechanical configuration of the foot is altered severely enough, gait deviations can be observed.

Functional Limitations

Impaired balance or a perception of instability due to diminished sensation or pain on the sole of the foot may be the only functional impairment that is reported by the patient. As a consequence, limited walking tolerance, reduced walking distance, stumbling, or falls may be reported by the patient.

Diagnostic Studies

Electrodiagnostic testing should be performed for any patient with clinically suspected tarsal tunnel syndrome; this is the only diagnostic study that evaluates the electrophysiologic function of the tibial nerve and its major terminal branches. Both needle electromyography and nerve conduction studies (i.e., motor, sensory, or mixed nerve studies) should be done. Furthermore, it is imperative that the tibial nerve be thoroughly evaluated from an electrophysiologic standpoint because either the tibial nerve or one or more of its terminal branches may be involved in clinically suspected tarsal tunnel syndrome [4,10]. A magnetic resonance imaging study may be useful in detecting a space-occupying mass that is impinging on or compressing the tibial nerve within the tarsal tunnel [12]. The magnetic resonance imaging study can also provide a “road map” for surgical exploration of the tarsal tunnel and then direct the procedure toward suitable anatomic decompression of the nerve [13]. The literature indicates that ultrasonography can be a complementary diagnostic imaging technique for cases of suspected tarsal tunnel syndrome by identifying space-occupying masses such as ganglia [14]. Plain radiographs and a bone scan may be needed to rule out a possible fracture or other bone lesion.

Treatment

Initial

Conservative measures can be effective in the majority of tarsal tunnel syndrome cases, and therefore most patients should be given an adequate trial, which is generally at least 3 to 6 months. Initial management usually includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and possibly a neuropathic pain medication (such as gabapentin). If there is a biomechanical foot condition that can be corrected or supported, the patient could benefit from a medial arch support (for a pronated foot) or a foot orthosis (for hindfoot valgus) [7]. In some patients, a short leg walking cast or boot brace can provide symptomatic relief [15].

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy can be useful in certain cases, most typically with modalities such as iontophoresis to reduce symptoms of inflammation, deep massage to mobilize scar tissue, desensitization, and various exercises—such as stretching exercises of the toe flexors, both active and passive, and of the ankle muscle groups (i.e., dorsiflexors, plantar flexors, invertors and evertors) along with specific nerve mobilization exercises [16]. Strengthening exercises for the toe flexors and extensors and for the ankle muscle groups may also be prescribed for distinct motor deficits with a goal of equalizing any muscle imbalance. In addition, gait training along with balance training, both static and dynamic, may be necessary. The patient may require extra-depth shoes to accommodate a medial arch support or a custom-made foot orthosis. Therefore an orthotist or pedorthist may need to manufacture these custom-made orthotics or footwear.

Procedures

For diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, a local anesthetic-steroid injection into the tarsal tunnel can give relatively immediate relief of local swelling and inflammation surrounding the tibial nerve.

Surgery

Surgical management consists of release of the flexor retinaculum and possibly exploration for a mass or space-occupying lesion and neurolysis of the tibial nerve, depending on the surgeon [1]. In addition, some surgeons advocate release of the superficial and deep fascia of the abductor hallucis to more completely decompress the tibial nerve and its terminal branches. The success rate (good to excellent outcome) for tarsal tunnel release is variable and reported to be 44% to 78%, depending on the study [13]. Endoscopic release of the tarsal tunnel may be a potential surgical option in some cases [13,17].

Potential Disease Complications

Several potential disease complications may be a consequence of tarsal tunnel syndrome. Skin breakdown, including ulcerations, can occur over the plantar aspect of the foot as a result of impaired sensation. An altered gait pattern may develop with decreased balance or a “feeling of unsteadiness” because of impaired sensation, particularly with respect to proprioception and light touch or pressure in the foot, or because the biomechanical configuration of the foot is distorted. Low back pain or lower extremity joint pain (probably hip or knee) may arise as a consequence of the gait deviation.

Potential Treatment Complications

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may cause, most commonly, gastric or renal complications. Skin breakdown can develop over the foot or ankle from a poorly fitting foot orthosis. Tendon rupture may occur after steroid injection into the incorrect location (e.g., flexor tendon sheath). In addition, the symptoms of pain, numbness, and paresthesias in the foot can be exacerbated after a local anesthetic-steroid injection or after surgical decompression of the tarsal tunnel.