CHAPTER 93

Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction

David Wexler, MD, FRCS (Tr & Orth); Todd A. Kile, MD; Dawn M. Grosser, MD

Definition

The tibialis posterior muscle, originating from the proximal tibia and fibula, passes distally with a broad insertion on the plantar aspect of the navicular, cuneiform, cuboid, and metatarsal bases and normally functions to invert the subtalar joint and to adduct the forefoot. Its principal antagonist is the peroneus brevis, which normally everts the subtalar joint and abducts the forefoot. Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction is a condition, as its name suggests, that is characterized by the loss of function of the posterior tibial tendon. This disabling problem may be caused by trauma, degeneration, or inflammatory arthritides and is most commonly seen in the sixth to seventh decades of life [2]. These pathologic processes can lead to reduction of effective excursion of the tendon or even rupture, resulting in progressive loss of the medial arch, midfoot abduction, and forefoot pronation. Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction is the most common cause of acquired flatfoot in the adult. Usually, posterior tibial tendon dysfunction is a chronic, progressive process, but spontaneous rupture can occur in patients receiving long-term steroid therapy or after trauma.

In regard to pathophysiology, the posterior tibial tendon functions in concert with the gastrocnemius-soleus complex to stabilize the hindfoot. The longitudinal arch is stabilized primarily by bone articulations and ligamentous structures (spring ligament, talocalcaneal interosseous ligament, superficial deltoid) and only secondarily supported by the posterior tibial tendon. The initial pathologic change is typically tendinosis of the posterior tibial tendon with maintenance of the longitudinal arch. As the tendon becomes less efficient, more stress is placed on the medial ligamentous structures, which attenuate, leading to progressive loss of the arch and abduction of the midfoot [3]. The posterior tibial tendon begins to atrophy while the flexor digitorum longus hypertrophies in an attempt to compensate [4]. Next, the calcaneus will drift into a valgus malalignment, changing the lever arm of the Achilles and causing a heel cord contracture. Finally, the peroneus brevis becomes an unopposed antagonist and exacerbates the deformity.

Symptoms

Patients, most commonly middle-aged women, primarily complain of pain on the inner or medial aspect of the ankle and the hindfoot. As the insufficiency progresses, pronation increases, leading to pain over the dorsolateral aspect of the midfoot [5,6]. Typically, this results in a gradual loss of the arch associated with a corresponding increase in pain.

Rarely, there is a history of a rapid collapse from rupture after an acute injury [7,8]. There have been only six reported cases in the literature of athletes (basketball players and runners) younger than 30 years with acute posterior tibial tendon ruptures [9–12].

Physical Examination

The physical examination reveals swelling confined to the area around the medial malleolus. In general, there is tenderness along the course of the tendon, and there may be exquisite tenderness just distal to the medial malleolus where the tendon most commonly tears [13,14].

Assessment of the lower extremity in the weight-bearing position best demonstrates the essential elements of the deformity: valgus hindfoot (calcaneovalgus), midfoot abduction, and forefoot pronation. This complex deformity clinically demonstrates a “too many toes” sign, that is, when the feet are viewed from behind, there appear to be more toes on the affected side than on the unaffected side. The severity of the patient’s presentation depends on the chronicity of the insufficiency and the magnitude of the tendon dysfunction. The medial longitudinal arch of the foot may be entirely lost.

The anterior tibial tendon may become more visible than on the normal side as the patient, subconsciously, tries to regain the arch. Patients may have difficulty walking on their tiptoes or have difficulty performing a one-sided toe-stand while holding on to the clinician’s hands. The heel fails to invert into a varus position. Asking the patient to invert the plantar-flexed foot against resistance can be overcome by the clinician’s hand. Assessment of the patient on the couch reveals altered posture of the foot due to the unopposed action of the peroneus brevis. A callosity can be seen in the region of the medial plantar aspect of the midfoot.

Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction can be classified in three stages that are correlated to the treatment. Stage I is a tenosynovitis, normal tendon function, and no deformity. Stage II is a spectrum of disease that includes tendinosis but also posterior tibial tendon dysfunction and weakness. Loss of the medial arch and progressive valgus of the heel with mild lateral impingement can be seen. Early in stage II, the patient may be able to perform a single heel raise, but as this stage progresses, this function is lost. Most important, the flexibility of the foot is maintained with nearly normal subtalar, midtarsal, and forefoot motion. This continuum of disease may progress to stage III as the deformity becomes more rigid and subtalar degeneration occurs with subsequent decreased motion. Lateral tenderness is present because of impingement of the distal fibula on the calcaneus. A heel cord contracture is also apparent in most cases.

Functional Limitations

Patients may experience fatigue after only limited activity as their gait mechanics change with progressive pronation. They may have difficulty finding well-fitting footwear. Pain is usually the greatest complaint and also limits walking and sports-related activities [15].

Diagnostic Studies

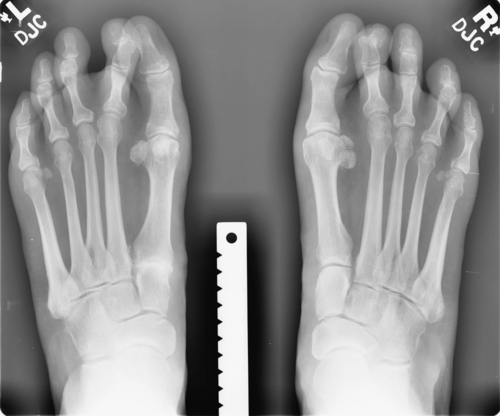

Weight-bearing foot and ankle radiographs are usually helpful, depending on the severity of the clinical findings. In the earlier stages of tenosynovitis, the radiographs are usually normal, even if there is some mild clinical flattening of the medial longitudinal arch. As the problem progresses, radiographic changes occur (Figs. 93.1 and 93.2). These include, on the anteroposterior view, uncovering of the head of the talus (as the navicular moves laterally) and increase of the angle between the bodies of the talus and the calcaneus; on the lateral view, plantar flexion of the talus, collapse of the navicular-cuneiform joint, and overlapping of the four medial metatarsals are noted.

Ultrasonography has been used in the past to visualize the posterior tibial tendon both statically and dynamically and to demonstrate the tendon’s excursion. Currently, the “gold standard” is magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate the continuity of the tendon. This provides a reasonably accurate view of the degree of inflammation and synovial fluid present within the tendon sheath as well as determines whether a tear of the tendon is present.

Treatment

Initial

The first line of management, in stage I of posterior tibial tendon insufficiency, is with orthoses. Custom orthotic devices with longitudinal arch support and medial heel lift shoe inserts, University of California Biomechanics Laboratory (UCBL) inserts, rigid ankle-foot orthoses, and even double upright braces may be necessary. Unfortunately, there is no proof that any orthotic device can halt progression of the disorder, and if the deformity is less flexible, orthoses may be poorly tolerated. On occasion, a short leg cast is applied for 4 to 6 weeks for rest. Patients who have enough pain to require a boot or cast are also given a prescription for a wheelchair and walker. They are advised to be minimally weight bearing for at least 2 weeks. If the pain improves, they may gradually progress weight bearing in the boot. When they are pain free with weight bearing in the boot, they progress to a cushioned lace-up shoe and arch support. Pain should be the guide as to how fast patients may progress weight bearing. Anti-inflammatory medication may help alleviate some of the pain from the tenosynovitis. In obese individuals, weight loss can be critical.

Rehabilitation

Once the acute inflammation has settled, an exercise program may be started to strengthen the posterior tibial tendon. This can include active-resisted exercises with elastic materials (such as Cliniband or Thera-Band) and an exercise akin to trying to “pick up carpet with the sole of the foot” or “grasping a towel.” Further methods include muscle stretching and strengthening techniques, particularly aimed at the Achilles tendon. Proprioceptive drills to improve balance on the wobble board and gait reeducation are also important.

Postoperative rehabilitation can include therapy for range of motion exercises after tenosynovectomy and most certainly after tendon transfer surgery to strengthen the muscle-tendon complex. After a subtalar or triple arthrodesis, the patient will have had a lengthy period of cast immobilization, and therefore gait reeducation can be beneficial.

Procedures

Injection of local anesthetic and steroid into the tendon sheath is a contentious subject and is not recommended because of the possibility of tendon rupture.

Surgery

Different surgical procedures are recommended, depending on the stage of the disease. Continuing pain and failure of nonoperative management of tenosynovitis (stage I) are the main indications for tenosynovectomy to remove all the inflamed synovium. This is followed by a period of cast immobilization. Repair of incomplete tears of the tendon may also be indicated and can be augmented by tendon transfers.

Complete tendon disruption, in the absence of bone collapse (stage II), can be treated with tendon transfers, combining a flexor digitorum longus transfer with a medial sliding calcaneal osteotomy. Subtalar or triple arthrodesis may be indicated for patients with progressively worsening deformity and lateral hindfoot pain (stage III) [16,17].

Postoperative gait analysis of patients after tendon transfer and osteotomy shows improvements compared with the preoperative analysis in ankle push-off power, step length, velocity, and cadence [18]. Long-term satisfaction with this procedure is high: 97% improvement in pain, 94% improvement in function, and 84% ability to wear shoes without modification or orthotic device [19].

Potential Disease Complications

Posterior tibial dysfunction can result in progressive pain and deformity, restriction of mobility, valgus deformity of the knee, and medial longitudinal arch ulceration as the medial midfoot collapses, causing increased pressure with weight bearing in this region.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Steroid injection can cause tendon rupture. Complications of surgery include wound infection (in an area that can be notoriously slow to heal) and nonunion or failure of fusion in attempted arthrodesis.