CHAPTER 92

Plantar Fasciitis

Paul F. Pasquina, MD; Leslie S. Foster, DO; Matthew E. Miller, MD

Definition

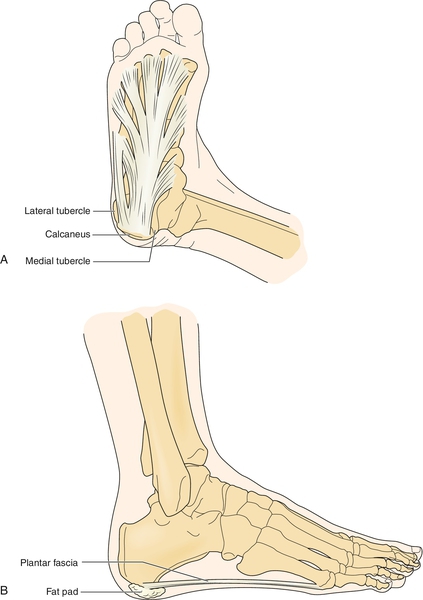

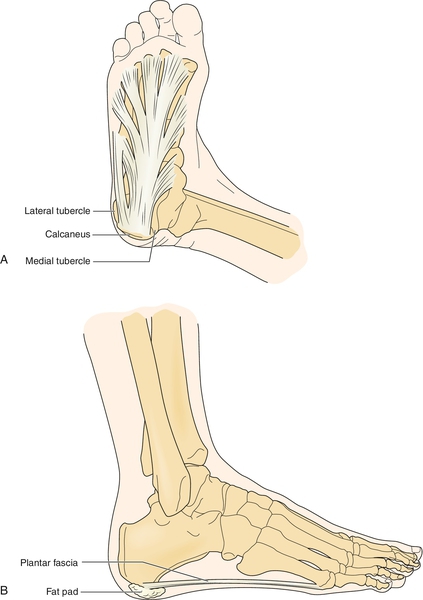

The plantar fascia is a multilayered fibrous aponeurosis that originates from the medial calcaneal tuberosity and extends distally, becoming wider and thinner and splitting into five bands. Each band then divides into a superficial and deep layer to insert onto the transverse tarsal ligament, flexor sheath, volar plate, and periosteum of the base of the proximal phalanges of the toes [1] (Fig. 92.1). Plantar fasciitis is an overuse injury resulting from repetitive microtears of the plantar fascia at its origin at the tuberosity of the os calcis deep to the distal medial heel pad [2]. It is classically described as a local inflammatory reaction, although recent research has demonstrated the relative absence of inflammatory cells in the injured tissue, suggesting more of a degenerative process; therefore, the terms tendinosis and fasciosis are advocated [3].

Plantar fasciitis is one of the most common injuries of runners. This condition occurs equally in both sexes in young people; some studies show that a peak incidence may occur in women 40 to 60 years of age [4]. The condition is typically precipitated by a change in the athlete’s training program. Such changes may include an increase in intensity or frequency, a decrease in recovery time, or a change in terrain or running surface. In the nonathlete, an increase in the amount of walking, standing, or stair climbing may also precipitate symptoms. There is a correlation of plantar fasciitis with professions requiring prolonged standing (e.g., police officers and hairdressers).

Risk factors such as pes planus (flat feet), pes cavus with rigid high arches, excessive pronation, obesity, Achilles tendon contracture, and poor footwear (usually a loose heel counter and inadequate arch support) may contribute to the development of this condition. Multiple authors have demonstrated that the successful treatment of plantar fasciitis is not contingent on the surgical removal of a heel spur (calcaneal enthesophyte). Studies have shown that only 50% of patients with plantar heel pain had a heel spur and that only 10% of patients with a heel spur were symptomatic [5].

Symptoms

Patients typically complain of sharp, knife-like pain in the plantar aspect of the heel at the base of the fascial insertion to the calcaneus. Pain is generally worse with standing or during the initial steps on awakening or after prolonged sitting. Patients will often complain of the classic “pain with the first steps in the morning” that eases after being up and about for a while. Plantar fasciitis foot support devices, such as arch supports or cushioned insoles, can help alleviate this pain and provide relief during daily activities. Pain also typically worsens at the beginning of an exercise session but decreases during exercise. The athlete may describe being able to “run through” the pain. Complaints of numbness, paresthesias, or weakness are atypical for plantar fasciitis; therefore, if these complaints are present, the clinician should suspect an underlying nerve injury.

Physical Examination

Palpation reveals tenderness at the origin of the fascia of the medial calcaneal tubercle, but there may be tenderness along the majority of the fascia. Range of motion often reveals limited great toe dorsiflexion from a tight plantar fascia as well as decreased ankle dorsiflexion from a tight Achilles tendon. Dorsiflexion should be tested with the knee straight (gastrocnemius on stretch) and with the knee bent (gastrocnemius relaxed, soleus on stretch) to better differentiate tightness of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. The neurologic examination should reveal normal muscle strength, sensation, and deep tendon reflexes, unless a concomitant neuropathy is present.

Functional Limitations

Depending on the severity of disease, patients may complain of symptoms only when they try to increase running intensity or distance. More severe cases may significantly limit a patient’s ability to ambulate during daily activities or climbing stairs. Professions requiring extensive walking or standing (e.g., postal workers, nurses, or waitresses) may require job modification as well as more aggressive splinting or even casting during the initial phase of treatment.

Diagnostic Testing

Plantar fasciitis is usually a clinical diagnosis. However, radiographs of the foot may be helpful in ruling out other potential causes of heel or foot pain. It is a common misconception that the pain of plantar fasciitis is the direct result of the often (50%) associated anterior calcaneal enthesophyte (heel spur). In fact, a study of 461 asymptomatic patients showed radiographic evidence of heel spurs in 27% of those studied [5].

Electrodiagnostic testing (electromyography) may be helpful in ruling out the possibility of a nerve entrapment.

Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging studies may be helpful before surgical intervention is considered; these studies may demonstrate signal changes or swelling within the fascia. Magnetic resonance imaging usually demonstrates edematous involvement of the calcaneal insertion of the plantar aponeurosis, with marked thickening of the central cord of the plantar fascia.

Treatment

Initial

As with most overuse injuries, initial treatment should follow the PRICEMM principles: protection, rest, ice, compression, elevation, medications, and modalities. Protection and rest usually involve “relative rest”; the patient avoids aggravating activities while maintaining cardiovascular and muscle fitness by participating in low-impact activities such as swimming, bicycling, and weightlifting. Ice massage to the plantar fascia can easily be performed by the patient at home. Have the patient put a Styrofoam or paper cup full of water into the freezer. Once the water becomes ice, the patient may massage the block of ice along the origin of the plantar fascia for approximately 10 to 15 minutes. Icing is most helpful after activities or at the end of the day. Compression by way of taping the sole of the foot or applying an elastic wrap around the foot may offer comfort to the patient, as may soft gel heel cups, which may be placed in the patient’s shoes. Casting in a neutral position helps in difficult cases. Keeping the foot elevated while sitting or lying down may also help reduce any local inflammation and swelling. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are often used to treat pain and any inflammatory component to the disease process. No studies have specifically examined the effectiveness of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone. More than 90% of patients with plantar fasciitis are cured with conservative measures [6]. Patients are often advised to obtain “stress mats” for prolonged standing on hard floors. Modalities are addressed in the following section.

Rehabilitation

The key elements of rehabilitation include stretching and strength training of not only the lower leg and foot but also the thigh, hip, and back. These include the plantar fascia, gastrocnemius-soleus complex, quadriceps, hamstrings, and hip flexors and extensors [7].

Increased flexibility is achieved through frequent stretching during the day. Each stretch should be held for 30 seconds. It is beneficial to tell patients that muscles need to be reminded to stay elongated; therefore it is better to stretch for 30 seconds 10 times per day than to dedicate an hour once a day to perform stretches. This also helps achieve the patient’s compliance.

Strengthening of the foot intrinsic muscles may be achieved by placing a towel on the floor and having the patient crunch up the towel into a ball and then spread it back out by flexing and extending the toes. Alternative aerobic exercises or “cross-training” should be prescribed to minimize the effects of deconditioning. This can generally be achieved with running or swimming in the pool as well as by low-resistance cycling.

Therapeutic modalities include local ultrasound, iontophoresis, and phonophoresis. Although there is little evidence in the literature to suggest that these modalities hasten the resolution of the underlying problem, they may be helpful in controlling the patient’s pain symptoms, thus allowing better participation in a rehabilitation exercise program. As symptoms resolve and the patient has achieved good flexibility as well as normal peroneal and posterior tibial muscle strength, a gradual return to sport is attempted. An appropriate return to running program should be established by the provider together with the patient. This can generally be achieved by having the patient start at half of the time or distance and intensity that he or she was running before the injury, divided into equal walk and jog intervals. For example, if a patient was running up to 30 minutes before the injury, an appropriate return to running schedule might be as follows: Alternate 4 minutes of walking with 1 minute of jogging for a total of 15 minutes. Increase by 5 minutes every week until 30 minutes is reached. Next, decrease the walk time intervals to 3 minutes each and increase the jog time intervals to 2 minutes. Each week, diminish walk time intervals by 1 minute and add 1 minute to the jog interval. Walk-jog sessions should be performed three times per week, allowing 24 hours of rest between workouts. If at any time the symptoms begin to reappear, return to the walk-jog intensity of the previous week for another week until advancing again. It is generally recommended to start on level surfaces before introducing hills. Patients must be cautioned to not “overdo it” and to stay within a structured rehabilitation program because reinjury is common.

Management of excessive foot pronation is essential to correction of a common contributing biomechanical factor [8]. This may be achieved simply by stretching the Achilles tendon; however, a change in footwear is often indicated. Numerous running shoes are on the market, and a good running shoe store with a knowledgeable staff may be helpful in finding the appropriate shoe for a particular type of foot. Essential components include a good heel counter and reasonable midfoot flexibility. Patients who demonstrate excessive hindfoot valgus and forefoot varus deformities typically benefit from custom-made orthotic devices that incorporate medial-side wedging. Patients should be cautioned about wearing high-heeled shoes, especially those with hard soles, as this will increase the forces across the plantar fascia as well as promote Achilles tendon shortening.

Procedures

Posterior night splinting may prove effective in resistant cases. Off-the-shelf devices are available, or fabrication of a posterior splint is simple with use of fiberglass casting tape. The patient’s foot should be splinted in maximum dorsiflexion to allow maximum lengthening of the plantar fascia and to prevent the stiffening and contraction that normally occur during sleep. The splint should be applied every evening and worn throughout the night for 2 to 3 weeks. If the patient finds wearing the splints uncomfortable at first, a gradual “break-in” period may be necessary, with the goal of wearing the splints throughout the night in 1 to 2 weeks. A study demonstrated that about 90% of patients with refractory symptoms improved after only 1 month of treatment [9].

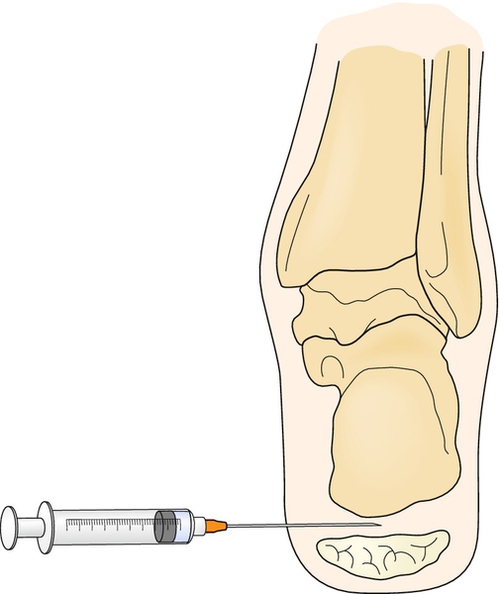

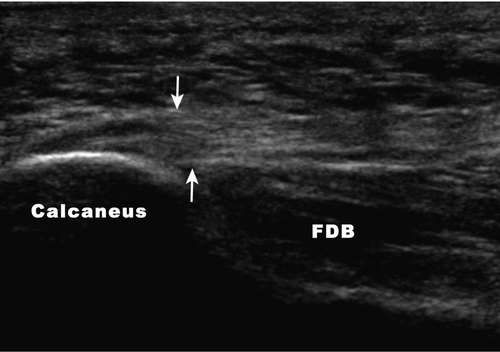

Corticosteroid injections can often be avoided if an effective treatment plan is adhered to. In refractory cases, however, a local steroid injection may allow the patient to be more compliant with the established rehabilitation program [10]. We prefer to inject a combination of 10 to 20 mg of triamcinolone (Kenalog) and 4 mL of 1% lidocaine with a 25-gauge, 1½-inch needle. A medial approach is used as it is generally better tolerated by the patient. The needle is aimed toward the medial tubercle of the calcaneus or most tender point, ensuring that the injection is above the fat pad to avoid potential fat pad atrophy (Fig. 92.2). Ultrasound guidance is now often used for more accurate injection with hopes of minimizing this complication (Fig. 92.3). Ultrasound-guided injection of dexamethasone sodium phosphate was shown to be safe and to provide some short-term benefit at 4 weeks [11].

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is a treatment that generates shock waves by electrohydraulic, piezoelectric, or electromagnetic methods. A meta-analysis evaluated 20 published studies that clinically supported this treatment method as effective for plantar fasciitis. Two mechanisms are hypothesized for this treatment’s efficacy. First, it is thought that the transmitted waves have an effect on pain receptor physiology. Second, the transmitted waves initiate fascial tissue healing through microtrauma and a subsequent healing response by the release of molecular agents and growth factors. An advantage to this treatment method is immediate weight bearing and return to most activities in 1 to 2 weeks [12].

Autologous blood injections have shown promise for recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Martin [13] injected 1 mL of lidocaine and 2 mL of autologous blood where the plantar fascia was most tender. This treatment has been shown to decrease pain severity and to increase functional activity.

Babcock and Foster [14] investigated the effect of botulinum toxin in refractory plantar fasciitis. This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study yielded significant improvements in pain relief and overall foot function at both 3 and 8 weeks after treatment.

Surgery

Surgery may be indicated in patients with significant disability and persistent pain when conservative measures have failed. The two most common surgical options are open and endoscopic release. Overall successful outcomes range from 48% to 90% [15]. A successful outcome could be expected for most patients who are treated for recalcitrant plantar fasciitis.

Potential Disease Complications

Patients who continue untreated and run through their pain typically have progressive symptoms, which begin to interfere with their activities of daily living and may lead to irreversible fascial degeneration and damage.

Potential Treatment Complications

Although corticosteroid injections may help selected patients to participate in a more effective rehabilitation program, this procedure should be performed with reservation because it may lead to heel fat pad atrophy or even plantar fascia rupture [16]. For this reason, it may be helpful to apply a walking splint or cast for several days after an injection.

Because of the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided, and they should be used with caution in elderly patients or those with a history of gastrointestinal or bleeding disorders. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to them.

Surgery, whether endoscopic or open, is associated with several risks (infection, complete rupture). Postoperative rehabilitation may require several weeks of limited or no weight bearing on the affected extremity.

[/level-membership-for-physical-medicine-and-rehabilitation-category]CHAPTER 92

Plantar Fasciitis

Paul F. Pasquina, MD; Leslie S. Foster, DO; Matthew E. Miller, MD

Definition

The plantar fascia is a multilayered fibrous aponeurosis that originates from the medial calcaneal tuberosity and extends distally, becoming wider and thinner and splitting into five bands. Each band then divides into a superficial and deep layer to insert onto the transverse tarsal ligament, flexor sheath, volar plate, and periosteum of the base of the proximal phalanges of the toes [1] (Fig. 92.1). Plantar fasciitis is an overuse injury resulting from repetitive microtears of the plantar fascia at its origin at the tuberosity of the os calcis deep to the distal medial heel pad [2]. It is classically described as a local inflammatory reaction, although recent research has demonstrated the relative absence of inflammatory cells in the injured tissue, suggesting more of a degenerative process; therefore, the terms tendinosis and fasciosis are advocated [3].

Plantar fasciitis is one of the most common injuries of runners. This condition occurs equally in both sexes in young people; some studies show that a peak incidence may occur in women 40 to 60 years of age [4]. The condition is typically precipitated by a change in the athlete’s training program. Such changes may include an increase in intensity or frequency, a decrease in recovery time, or a change in terrain or running surface. In the nonathlete, an increase in the amount of walking, standing, or stair climbing may also precipitate symptoms. There is a correlation of plantar fasciitis with professions requiring prolonged standing (e.g., police officers and hairdressers).

Risk factors such as pes planus (flat feet), pes cavus with rigid high arches, excessive pronation, obesity, Achilles tendon contracture, and poor footwear (usually a loose heel counter and inadequate arch support) may contribute to the development of this condition. Multiple authors have demonstrated that the successful treatment of plantar fasciitis is not contingent on the surgical removal of a heel spur (calcaneal enthesophyte). Studies have shown that only 50% of patients with plantar heel pain had a heel spur and that only 10% of patients with a heel spur were symptomatic [5].

Symptoms

Patients typically complain of sharp, knife-like pain in the plantar aspect of the heel at the base of the fascial insertion to the calcaneus. Pain is generally worse with standing or during the initial steps on awakening or after prolonged sitting. Patients will often complain of the classic “pain with the first steps in the morning” that eases after being up and about for a while. Pain also typically worsens at the beginning of an exercise session but decreases during exercise. The athlete may describe being able to “run through” the pain. Complaints of numbness, paresthesias, or weakness are atypical for plantar fasciitis; therefore, if these complaints are present, the clinician should suspect an underlying nerve injury.

Physical Examination

Palpation reveals tenderness at the origin of the fascia of the medial calcaneal tubercle, but there may be tenderness along the majority of the fascia. Range of motion often reveals limited great toe dorsiflexion from a tight plantar fascia as well as decreased ankle dorsiflexion from a tight Achilles tendon. Dorsiflexion should be tested with the knee straight (gastrocnemius on stretch) and with the knee bent (gastrocnemius relaxed, soleus on stretch) to better differentiate tightness of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. The neurologic examination should reveal normal muscle strength, sensation, and deep tendon reflexes, unless a concomitant neuropathy is present.

Functional Limitations

Depending on the severity of disease, patients may complain of symptoms only when they try to increase running intensity or distance. More severe cases may significantly limit a patient’s ability to ambulate during daily activities or climbing stairs. Professions requiring extensive walking or standing (e.g., postal workers, nurses, or waitresses) may require job modification as well as more aggressive splinting or even casting during the initial phase of treatment.

Diagnostic Testing

Plantar fasciitis is usually a clinical diagnosis. However, radiographs of the foot may be helpful in ruling out other potential causes of heel or foot pain. It is a common misconception that the pain of plantar fasciitis is the direct result of the often (50%) associated anterior calcaneal enthesophyte (heel spur). In fact, a study of 461 asymptomatic patients showed radiographic evidence of heel spurs in 27% of those studied [5].

Electrodiagnostic testing (electromyography) may be helpful in ruling out the possibility of a nerve entrapment.

Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging studies may be helpful before surgical intervention is considered; these studies may demonstrate signal changes or swelling within the fascia. Magnetic resonance imaging usually demonstrates edematous involvement of the calcaneal insertion of the plantar aponeurosis, with marked thickening of the central cord of the plantar fascia.