CHAPTER 91

Morton Neuroma

Sammy M. Lee, DPM; Robert J. Scardina, DPM

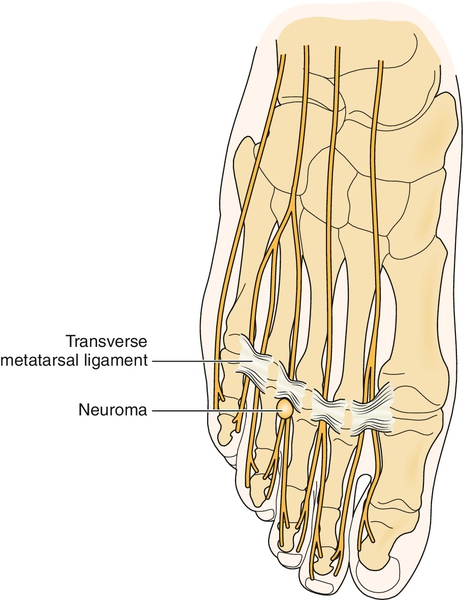

Definition

Morton neuroma is not a neoplasm; rather, it is a local, mechanically induced, degenerative enlargement of the third plantar intermetatarsal nerve with associated perineural fibrosis [1] caused by an accumulation of collagenous material within the sheath of Schwann and usually the result of repetitive trauma (Fig. 91.1). As such, it is more accurately defined as an intermetatarsal compression or entrapment neuropathy [2]. The exact etiology has not been clearly identified or proved conclusively, but the following have been postulated as contributing factors: flatfoot (pes planus); anterior splay foot; high-arch foot (pes cavus); equinus deformity [3]; ill-fitting (tight or high-heeled) shoes; abnormal proximity of neighboring metatarsal heads [4]; and associated forefoot deformities, including hallux abductus, bunion, and lesser hammer toes. Plantar intermetatarsal nerves of the foot are purely sensory at and distal to the level of the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints, as they course through a fibro-osseous canal composed of neighboring metatarsal heads and the overlying deep transverse intermetatarsal ligament [5]. Anatomic (cadaver) studies have identified the third intermetatarsal nerve as most commonly receiving proximal branches from both the medial plantar and lateral plantar nerves, each arising from the common posterior tibial nerve. Therefore, anatomically, the third intermetatarsal nerve is usually enlarged to some degree as it develops from proximal trunks of two separate nerve branches. This anatomic configuration may or may not be a causative factor. The classic Morton neuroma occurs in the third intermetatarsal space. Similar nerve compression neuropathies occur, but less commonly, in the second plantar intermetatarsal space (Hauser neuroma) and rarely in the first (Heuter neuroma) and fourth (Iselin neuroma) plantar intermetatarsal spaces [2]. Symptomatic plantar neuromas in neighboring intermetatarsal spaces may occur in the same foot, but uncommonly. They are all treated in a similar fashion.

Symptoms

Morton neuroma may be manifested symptomatically in a variety of ways: localized sharp, lancinating, or burning pain; paresthesias and dysesthesias; numbness and tingling; and toe cramping. Symptoms typically radiate distally, involving the opposing plantar sides of the third and fourth toes, but pain exclusively in the fourth toe is not uncommon. Unilateral presentation is most common, whereas bilateral is less so. Symptoms occur predominantly during weight-bearing activities, but residual non–weight-bearing or nocturnal pain is sometimes present. Not uncommonly, patients may experience symptoms while driving an automobile with the foot held in a slightly dorsiflexed position. A characteristic patient maneuver is to remove the shoe and massage or manipulate the plantar forefoot and MTP joints, producing transient relief of symptoms [6].

Physical Examination

On inspection, the foot may appear normal or may demonstrate a subtle divergence of the third and fourth toes, usually more pronounced with weight bearing. When it is present, the regional palpable pain is typically plantar. The lateral forefoot squeeze test may mimic a tight shoe, thereby reproducing symptoms. In long-standing cases, hypoesthesia or anesthesia may be noted in the third interdigital web space, distally on the opposing plantar sides of the involved toes (toe tip sensation deficit [7]) or plantar, distal to the third and fourth metatarsal heads. The most diagnostic and reliable clinical maneuver is the Mulder test [8], performed by alternating lateral compression of the forefoot with one hand and dorsal-plantar compression of the involved distal intermetatarsal space with the opposite forefinger and thumb (Fig. 91.2) [6]. A Mulder sign is considered present when symptoms are reproduced and a palpable and sometimes audible click is detected. In general, there are no signs of proximal nerve involvement (e.g., tarsal tunnel syndrome), vasomotor instability, or arterial insufficiency. Predisposing foot types (pes planus or pes cavus) or a tight Achilles tendon (equinus) [3] may be evident on clinical examination. Passive range of motion of the neighboring MTP joints is usually pain free without crepitus. Unilateral antalgic (pain-avoidance) gait may also be observed.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations include difficulty with walking or running any significant distance and in performing other weight-bearing physical activities as well as the inability to wear dress shoes comfortably (particularly women’s high heels).

Diagnostic Studies

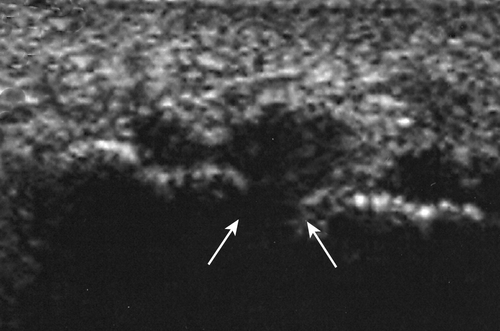

The diagnosis of Morton neuroma is generally made from history and clinical examination. However, other supportive diagnostic studies may be helpful in establishing a diagnosis, especially when surgical intervention is being considered or in the event of failed conservative measures. Ultrasonography is a relatively simple, inexpensive, and helpful diagnostic tool [9,10]. In the evaluation of a primary neuroma, a 5-mm or greater hypoechoic mass, visualized in the coronal (frontal) plane projection between the neighboring metatarsal heads, is considered a positive finding [11,12]. Magnetic resonance imaging, although generally not recommended in the initial evaluation, may also be used, particularly in the presence of equivocal or normal ultrasonographic findings (e.g., small lesions) and when surgical excision is being considered [13–15]. Ultrasonography has a slightly higher sensitivity than magnetic resonance imaging, particularly for neuromas smaller than 5 mm in diameter [16]. Both ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging are used in the diagnosis of postsurgical recurrent or “stump” neuroma [17–19]. Performance of the Mulder test during sonography is a recently described real-time imaging method, helpful in assessing the dimensions of the nerve as well as the local “dynamics” of the pathologic process (Fig. 91.3) [11]. New high-resolution, high-frequency ultrasound scanning may provide a means of differentiating a neuroma from disease of neighboring soft tissue structures, including the plantar plate and flexor tendons [12]. The neuroma itself is not visible by plain radiographic imaging, but radiographs may be obtained to rule out metatarsal stress fracture, MTP joint disease (degenerative or inflammatory), or contributing neighboring metatarsal head abnormality. Sensory nerve conduction studies can be used, but because of the difficulty in isolating individual nerve trunks or branches, results are not consistently accurate or helpful. Differential latency testing is a new electrodiagnostic approach that is more sensitive, simpler to use, and less painful than conventional electrodiagnostic studies, and it requires no extra equipment. Values above 0.17 millisecond between branches of the common plantar interdigital nerves are consistent with Morton neuroma [20]. Last, a local anesthetic plantar intermetatarsal space injection can be a useful minimally invasive diagnostic maneuver to support the diagnosis.

Treatment

Initial

Conservative treatment modalities include shoe gear modifications (e.g., wider toe box), adhesive tape strapping or padding of the foot, and use of foot orthoses. Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics may provide some relief from acute symptoms but are not recommended for long-term treatment. Posterior lower leg stretching exercises may be helpful in the presence of gastrocnemius equinus.

Rehabilitation

Physiotherapy modalities, including both iontophoresis and phonophoresis, may help manage acute pain. If symptoms respond to initial conservative “mechanical” measures, such as off-the-shelf arch supports, more individualized therapies such as custom foot orthoses may provide additional symptomatic relief; these usually require referral to a podiatrist or pedorthist for fabrication.

Procedures

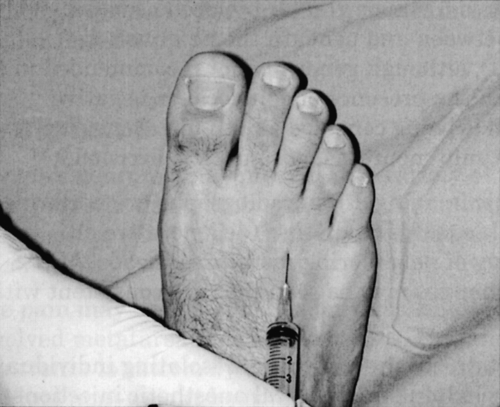

Injections with sclerosing agents, such as absolute alcohol [21,22], phenol, and vitamin B12, may be used if initial conservative noninvasive treatments fail. Local anesthetic-corticosteroid injections [15,23], however, are more commonly used and may provide transient (but rarely long-term) relief of symptoms (Fig. 91.4). These injections are limited to no more than three within a 3- to 6-month period because of the potential for plantar fat pad atrophy and MTP joint tendon or ligament rupture. Cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation have been used with mixed results and with a potential for iatrogenic injury to neighboring soft tissue structures.

Surgery

Conservative measures do not always result in symptomatic improvement [24]. The neuroma as well as the distal digital branches and proximal nerve trunk may be too large for their confined anatomic space. In these cases, surgical excision may be necessary [25]. The success rate of surgical excision is approximately 85% to 90%, and surgical revision or reexploration generally carries a poor prognosis [26]. Less traditional surgical techniques include neurolysis, decompression with dorsal nerve transposition [27], transection of the deep transverse intermetatarsal ligament (open or endoscopic), laser treatment (vaporization), distal lesser metatarsal osteotomies, and gastrocnemius recession (in the presence of soft tissue equinus deformity) [28–31].

Potential Disease Complications

Potential disease complications include persistent refractory or intractable nerve pain, reduced mobility, functional limitation, and shoe gear restrictions.

Potential Treatment Complications

Few complications may arise from conservative measures, such as padding, strapping, foot orthoses, and shoe modifications. On occasion, ipsilateral or contralateral knee, ankle, hip, or even low back pain may occur, but these respond rapidly after discontinuation of treatment. Likewise, there are no significant treatment complications from physiotherapy measures when they are used and applied properly. Long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may lead to gastrointestinal irritation.

Injection therapy with corticosteroids may result in plantar fat pad atrophy and secondary metatarsalgia or MTP joint plantar plate or collateral ligament rupture and subsequent digital deformity. Injection therapy with sclerosing agents may result in perineural irritation, inflammation, and pain. Postsurgical complications include infection, hematoma, vascular compromise, dorsal cutaneous nerve injury, incomplete resection, recurrence [32,33], stump neuroma [34], plantar fat pad atrophy, painful hypertrophic scar formation (especially with plantar incision approach), and reflex sympathetic dystrophy [32,33].