CASE 9 Unprotected Left Main Coronary Intervention

Cardiac catheterization

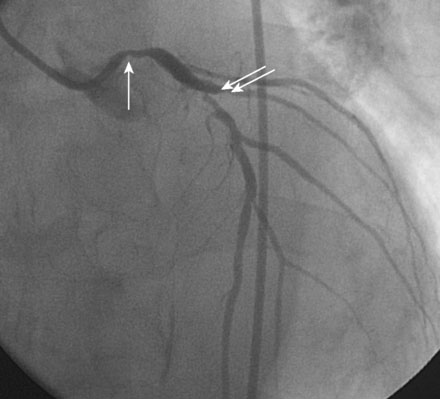

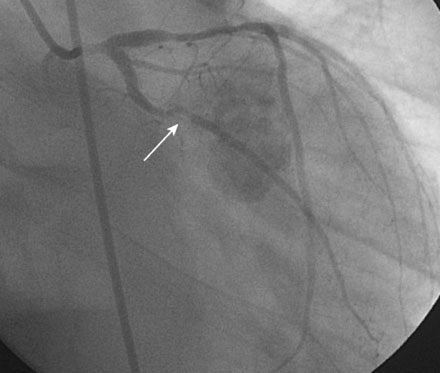

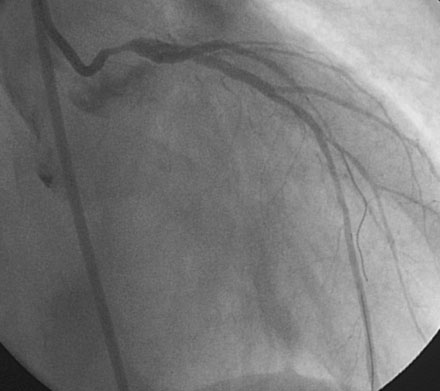

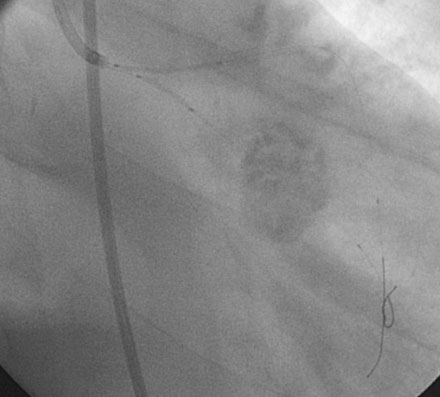

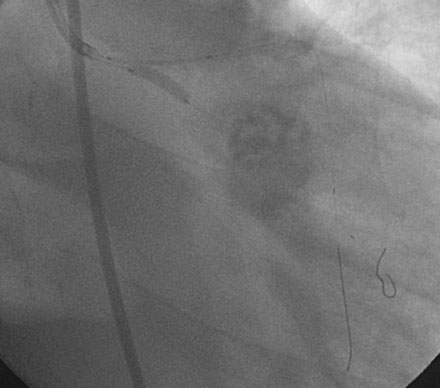

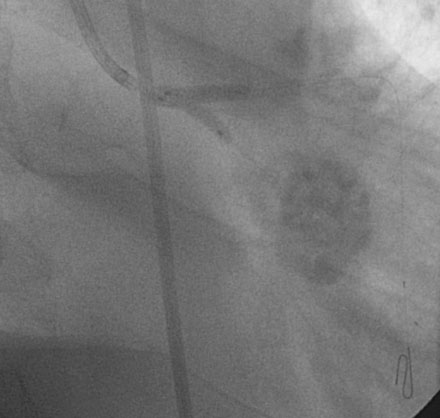

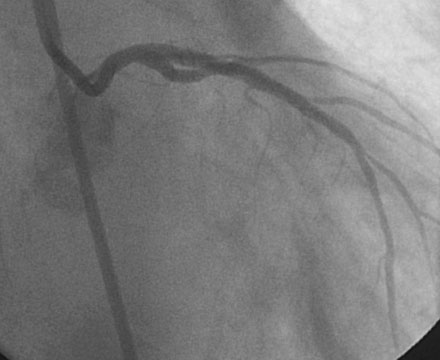

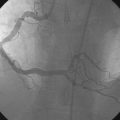

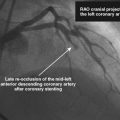

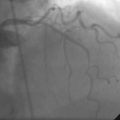

Obtaining arterial access proved challenging as his longstanding paraplegia resulted in substantial lower extremity atrophy and contracture at the hip. The femoral pulses were barely palpable; however, the right femoral artery was finally accessed successfully using ultrasound guidance, and angiography showed a small, diseased external iliac (Figure 9-1). The right coronary artery was without significant disease (Figure 9-2). Upon engagement of the left coronary artery, the operator observed pressure damping and ventricularization. The left main stem was severely diseased at the ostium (Figures 9-3, 9-4 and Videos 9-1, 9-2). In addition, there was significant obstructive disease noted in the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) and circumflex (LCX) arteries.

The operator inserted an 8 French sheath in the right femoral artery and procedural anticoagulation was achieved with bivalirudin; he had already been on clopidogrel therapy. An 8 French, left Judkins guide catheter was engaged and floppy-tipped guidewires passed into the LAD and LCX. The lesions in the LAD and LCX were treated successfully with balloon dilatation followed by placement of paclitaxel-eluting stents (Figure 9-5).

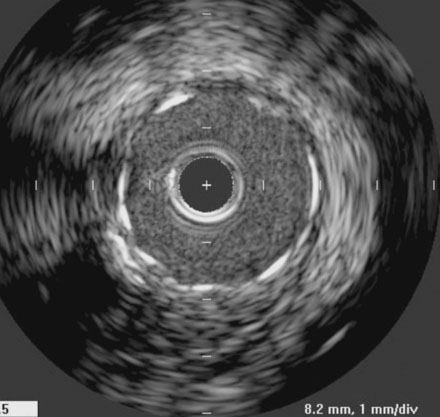

In order to protect the circumflex artery, the operator chose to use a modified “crush stent” technique to treat the left main stem lesion. Two stents were positioned in the left main/LAD and LCX: a 3.0 mm diameter by 20 mm long paclitaxel-eluting stent in the left main into the LAD, and a 3.0 mm diameter by 12 mm long paclitaxel-eluting stent in the circumflex (Figure 9-6). The left circumflex stent was deployed first (Figure 9-7); following this, the stent catheter and wire was removed from the circumflex artery and the left main stent deployed (Figure 9-8). The operator re-crossed the circumflex stent with another 0.014 inch guidewire and simultaneously inflated two 3.0 mm diameter noncompliant balloons (“kissing balloons”) to high pressure (Figure 9-9). A 3.5 mm noncompliant balloon was used to postdilate the left main stem. The final angiographic result was excellent (Figures 9-10, 9-11 and Videos 9-3, 9-4). Intravascular ultrasound was used to assess stent deployment and showed excellent stent apposition and a widely patent lumen (Figure 9-12).

Discussion

Left main stem disease is traditionally treated with bypass surgery, and this mode of revascularization is generally accepted as the standard of care for this high-risk subgroup. Percutaneous intervention of unprotected left main stem disease (i.e., without a patent bypass graft to one or more branches of the left coronary artery) has generally been reserved for patients too unstable for bypass or, as in this case, for patients who are not surgical candidates. However, there is a growing interest in and experience of treating this disease with stents instead of bypass surgery. Numerous registries and nonrandomized comparative trials have shown feasibility, relative safety, and efficacy of left main stenting using both bare-metal and drug-eluting stents.1 These data suggest that left main stenting can be done, but do not answer the question of whether it should be done. Only randomized, controlled trials comparing left main PCI to bypass surgery can answer that question, and PCI would need to show equivalence to bypass surgery in order to gain a Class I recommendation.

Left main stem stenting is a high-risk lesion subset for several reasons. First, the left main stem supplies a very large vascular territory and there is the potential for cardiovascular collapse with ischemia, particularly if the left coronary is dominant, the right coronary is occluded, or left ventricular function is reduced. Patients with left main coronary disease often have other disease requiring revascularization; isolated involvement of the left main stem occurs in only 9% of patients with left main stem disease.2 Often, this other disease is extensive or not amenable to percutaneous approaches, thus favoring surgical revascularization. Furthermore, left main stem disease involves the bifurcation in more than half the cases, introducing additional complexity and risk. Finally, the occurrence of either restenosis or stent thrombosis may be fatal events in patients with left main stents.

Several randomized controlled trials comparing bypass surgery to drug-eluting stents for treatment of left main disease are in progress or have been reported. A small series of 105 patients randomized to PCI versus surgery found similar anginal status at 12 months, but better left ventricular ejection fraction, shorter length of stay, and lower rate of adverse events at 12-month follow-up in the group randomized to stenting.3 The SYNTAX trial was a much larger randomized controlled trial that included patients with three-vessel or left main disease and compared stenting to bypass surgery.4 In the subgroup of patients with left main disease, patients treated with stents had similar rates of death and MI as patients treated with bypass surgery. Similar to the multivessel PCI versus CABG trials, patients treated with stents had a significantly higher rate of repeat revascularization. In the SYNTAX trial, the patients treated with bypass surgery had a higher rate of stroke.

Based on the SYNTAX trial, the most recently revised guidelines changed the classification of left main stenting from Class III to Class IIb, with several important caveats.5 Patients considered for left main stenting must have lesions suitable for PCI. Complex bifurcations and patients with multivessel disease are better served with surgery. Furthermore, the guidelines suggest that only experienced operators, backed-up by surgeons and competent support staff, should consider PCI of left main lesions.

There are several other issues and concerns relating to left main stenting. Regarding the choice of drug-eluting stent, based on the ISAR LEFT MAIN study, there does not appear to be a difference in outcomes in patients with left main disease treated with paclitaxel-eluting compared to sirolimus-eluting stents.6 Late stent thrombosis is a concern in this subgroup, as thrombosis of a left main stent would likely prove fatal. In the ISAR LEFT MAIN trial, no late thrombosis was seen beyond 30 days, alleviating this worry in this population. There is also uncertainty about how best to follow these patients after stenting. Many practitioners have advocated the performance of routine coronary angiography at 6 to 9 months; however, the most recent guidelines do not recommend this practice.

Selection of patients is clearly important in deciding on the optimal method of revascularization in this subgroup. In patients undergoing left main PCI, the most significant predictor of a major adverse event and repeat revascularization is bifurcation involvement.7 Treatment of bifurcation disease remains challenging, but nonbifurcation left main PCI has very favorable outcomes. The SYNTAX score can help choose the optimal revascularization strategy in patients with complex CAD including left main stem disease.8 This score takes into account disease complexity and the presence of additional disease; the higher the SYNTAX score, the better the outcome with CABG compared to PCI.

1 Taggart D.P., Kaul S., Boden W.E., Ferguson T.B., Guyton R.A., Mack M.J., Sargeant P.T., Shemin R.J., Smith P.K., Yusuf S. Revascularization for unprotected left main stem coronary artery stenosis: Stenting or surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:885-892.

2 Ragosta M., Dee S., Sarembock I.J., Lipson L.C., Gimple L.W., Powers E.R. Prevalence of unfavorable angiographic characteristics for percutaneous intervention in patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;67:357-362.

3 Buszman P.E., Kiesz S.R., Andrzej Bochenek A.J., et al. Acute and late outcomes of unprotected left main stenting in comparison with surgical revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:538-545.

4 Serruys P.W., Morice M.C., Kappetein A.P., et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961-972.

5 Kushner F.G., Hand M., Smith S.C., et al. Focused Updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update): A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2205-2241.

6 Mehilli J., Kastrati A., Byrne R.A., Bruskina O., Iijima R., Schulz S., Pache J., Seyfarth M., Maßberg S., Laugwitz K.L., Dirschinger J., Schömig A., ISAR-LEFT-MAIN (Intracoronary Stenting and Angiographic Results. Drug-Eluting Stents for Unprotected Coronary Left Main Lesions) Study Investigators: Paclitaxel- versus sirolimus-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1760-1768.

7 Biondi-Zoccai G.G.L., Lotrionte M., Moretti C., et al. A collaborative systematic review and meta-analysis on 1278 patients undergoing percutaneous drug-eluting stenting for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2008;155:274-283.

8 Sianos G., Morel M.A., Kappetein A.P., Morice M.C., Colombo A., Dawkins K., van den Brand M., Van Dyck N., Russell M.E., Mohr F.W., Serruys P.W. The SYNTAX Score: an angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. Euro Intervention. 2005;1:219.