community. Policy responses to be discussed include the Productivity Commission report and the subsequent Council of Australian Government (COAG) responses. Powerful health professional groups perceived several of the key recommendations in the policy responses as professional substitution strategies which would lead to a diminution of the relative position of their occupational group. In the latter part of the chapter the focus is on the role of professional substitution and delegation models to illustrate the volatile and contested nature of some reform strategies. The health workforce is a perennial problem in Australia, which is usually dealt with piecemeal by increasing either nursing or medical numbers after levels have reached so-called ‘crisis’ proportions, but for these professions it is now becoming an emerging problem as major structural reforms are suggested.

IDENTIFYING THE HEALTH WORKFORCE PROBLEM

Working together to create solutions, as urged by WHO, at local, national and global levels, is inherently complex. The need to draw together a diverse cohort of actors and agencies made up of individual practitioners, health service organisations, professional associations, government agencies of various jurisdictions, and education, health, aged care and community service agencies in both public and private sectors at each jurisdictional level is complicated. Other actors with a stakeholder interest in healthcare range from consumer advocacy groups through to political decision makers.

The definition of the ‘problem’ in relation to health workforce, and the consequent ‘solutions’, are highly contested in each national context because of the multi-professional nature of the stakeholders that constitute the clinical workforce (medical, nursing and allied health professions). This is made worse by the shift in inter-professional authority relations that frequently accompanies workforce reform agendas (Fournier 2000, Hunter 1996). The public perception of the quality and safety of health services, and its nexus to political outcomes, is a strong indicator of the political sensitivity of health policy generally, and health workforce policy specifically.

The recent backlash against overseas trained medical practitioners and the emergence of ‘medical racism’ following the Dr Patel (‘Dr Death’) case at Queensland’s Bundaberg Hospital is reflective of that sensitivity (Haikerwal 2005, and see Ch 15). The contemporaneous concerns about the national supply and regional maldistribution of health service practitioners, and vociferous criticism of the quality of medical education in the public media, for example, anatomy training (Cresswell 2007), has served to portray the health workforce as in ‘crisis’, rather than as a problem to be solved. Workforce indicators, focusing events, and the community’s susceptibility to politicised reports all work in concert to keep health workforce on the policy agenda (Kingdon 1995).

Health workforce as an arena of contest

Hall (2005 p 66), commenting on the inherently political nature of workforce planning, noted: ‘If healthcare policy is a strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principle (Sax 1984), workforce planning is one of the arenas for the contest’. And within that ‘contest’, the concept of professional boundary change or substitution as desirable workforce strategies is one of the most vigorously debated. At the front-line of contestability are the competing positions on how substitution strategies will be put into effect. The discussion on ‘professional substitution’ later in the chapter allows us to make visible one of Kingdon’s important conclusions about how particular constructions of ‘problems’ and ‘solutions’ interact together in a ‘policy primeval soup’ to advance on the political agenda. ‘Getting people to see new problems, or to see old problems in one way rather than another, is a major conceptual and political accomplishment’ (Kingdon 1995 p 115).

Health workforce complexity and multi-professionalism

A feature of the healthcare system in developed countries is the inherent complexity of the multi-professional workforce that provides services. Multi-professionalism has been identified as a key difficulty in health sector organisational reform because of the different values, practices, identity and autonomy of the various groups (Braithwaite & Westbrook 2005; Callan et al. 2007). This complexity is increasingly apparent, both vertically and horizontally, within the workforce. The number of distinct professions and occupations providing and supporting care has grown, as has the internal differentiation within these groups through the emergence of specialities and super-specialties (Weiner 2002). Traditionally a feature of medicine, this progressive specialisation toward speciality-based practice, and some would argue fragmentation, is increasingly evident in the nursing and allied health professions.

The proliferation of professional and occupational categories is well illustrated by attempts to define membership of the Australian allied heath professions. In the original survey a list of 68 ‘possible inclusions’ was ultimately reduced to 13 professions ‘generally included’ as part of the allied health collective. A further 35 were considered as ‘variously included’ depending on the context (O’Kane & Lowe 2003). The general shift over recent decades from conceptualising healthcare as services provided by medical professionals to one in which inter-professional care and teamwork is the dominant discourse reflects the progressive complexity of coordinating care.

Indicators of health workforce problems

Kingdon (1995) has highlighted the importance of indicators for capturing the scope and volatility of ‘problems’. The way in which indicators are presented can suggest certain policy solutions. Quantifiable indicators are valued highly and the health workforce arena is replete with indicators that are eminently ‘countable’. For example:

- the ratio of professionals per 100,000 population

- professionals in rural geographical areas vis-à-vis urban areas

- vacancy rates in health service organisations

- graduates per professional education program

- changes in practitioner numbers over time

- gender ratios and consequences of feminisation on workforce capacity

- professionals in part-time practice and their hours

- ageing of the health workforce as a percent of the workforce over 45 years of age etc.

- professionals in rural geographical areas vis-à-vis urban areas

The indicators that are the most powerful in shaping the perception of a ‘crisis’ in the Australian health workforce are twofold.

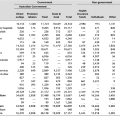

1. Continuing shortages despite a protracted period of growth

The investment in expansion of the health professions is evident from the growth rates reported in the inter-census analysis period of 1996–2001. Table 9.1 (overleaf) shows the growth rates for the key health professional groups, all health occupations and population increase, based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) figures (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] 2003). The growth rates for allied health occupations, at 26%, far exceeded that of medical occupations at 12%, and nursing occupations at 5%. All health occupations grew at 11% and population growth for the period 1996–2001 was 6%. More recent data from the ABS for the years 2000 and 2005 showed that the health workforce grew by 26% while all occupations grew by 10% over the same period (AIHW 2006).

|

Table 9.1 Relative growth in Australian health occupations 1996–2001 |

|

| Occupation group/Segment | Percent |

|---|---|

| Allied health occupationsa | 26.6 |

| Medical occupations | 12.6 |

| Nursing occupations | 5.4 |

| All health occupations | 11.4 |

| Population growth | 6.0 |

|

Source: compiled from data from AIHW 2003 pp 20–4 |

|

|

aData excludes medical imaging workforce (+25.0%), pharmacy workforce (+13.0%) and social work workforce (+26.7%) as these are not included in the ABS allied health category. |

|

Although these growth figures suggest a robust health workforce, the trends related to occupational exits, lower working hours, impending retirements, regional maldistribution and increasing demand for service from the population suggest a different picture. The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR) Migration Occupations in Demand List (MODL) specifies those occupations and specialisations in short supply. Twenty-six of the 43 entries in the professionals section of the 2006 MODL are health-related occupations. Table 9.2 shows the occupations listed as in demand. Of the 26, 13 are medical, 8 are from the allied health professions and 3 are nursing. The preponderance of health professions listed to be in shortage in Table 9.2 sits in sharp contrast to the picture of robust growth in Table 9.1.

|

Table 9.2 Health professions in demand |

|

| Health professionals – Migration Occupations in Demand List (MODL) 2006 | |

|---|---|

| Anaesthetist | Physiotherapist |

| Dental Specialist | Podiatrist |

| Dentist | Psychiatrist |

| Dermatologist | Radiologist |

| Emergency Medicine Specialist | Registered Mental Health Nurse |

| General Medical Practitioner | Registered Midwife |

| Hospital Pharmacist | Registered Nurse |

| Medical Diagnostic Radiographer | Retail Pharmacist |

| Obstetrician and Gynaecologist | Specialist Medical Practitioners (nec) |

| Occupational Therapist | Specialist Physician |

| Ophthalmologist | Speech Pathologist |

| Paediatrician | Sonographer |

| Pathologist | Surgeon |

|

Source: Compiled from Department of Immigration and Citizenship data. Online. Available: http://www.immi.gov.au/skilled/general-skilled-migration/skilled-occupations/occupations-vin-demand.htm [accessed18 Mar 2007] |

|

2. A projected significant reduction in total workforce entrants: all industries

The figures in Table 9.1 and Table 9.2 relate to immediate past growth and current shortages of health occupations in demand. Adopting a longer term view for the decade 2020–2030, and broadening the labour market analysis outside health to an all-industries perspective, the prospect for a sustainable health workforce are gloomy, despite the relative attractiveness of health careers. Current total workforce entrants (all occupations, all industries) are approximately 170,000 persons. This is projected to decline to 125,000 for the decade of 2020–2030, or a mere 12,500 persons per annum (Access Economics 2001).

Sustainability of new entrant policies

Taken together, the negative direction of most of these indicators has raised issues about the sustainability of the workforce to meet future demand (AIHW 2006). Many of these indicators readily suggest solutions on the supply side of the workforce capacity dynamic; that is, to ‘pump prime’ places for more students to enter the professions. The policy task is ‘easier’ at the front end of the workforce pipeline. Creating more student places is an easier implementation task when considered against the relative difficulty of ascertaining why professionals are leaving the industry, reducing their hours, or retiring early, and then developing the multiple policy responses needed to reverse these trends (Black et al. 2004). Policy instruments which must be carried out at the organisational or workplace level of diverse health service organisations are inherently more difficult because their implementation is open to shifting levels of commitment and resourcing by organisational-level leaders in the various state and territory jurisdictions.

Policy approaches, which rely extensively on funding new student places, particularly for medical students, have been criticised for unduly draining resources from other effective public health strategies. Reflecting on the American case, Weiner (2002 p 161) argues, ‘US taxpayers now contribute more than $500,000 to train each MD [doctor of medicine]. Moreover, an active US doctor typically generates at least that much in annual healthcare spending. If the real goal is to improve the population’s health, there are many other ways to use such massive resource infusions’.

Gathering rigorous qualitative and quantitative empirical evidence rather than relying on assumptions about the motivations for workforce participation is essential. The motivations cannot be assumed to be identical across professions; for example, it is an assumption that motivators and stressors for nursing are identical to those in the allied health professions. Nor should the individual professions be reduced to a homogenous set of interests. Robust sampling strategies are needed to discriminate between generational, gender and lifecycle segments within the professional group so that policy initiatives are not blunt instruments.

Profession-centred workforce planning

A major problem with the traditional profession-specific approach to workforce planning is the failure to grasp, and respond to, the inherent interdependence between the professions when in practice settings. ‘Pump priming’ in one area can produce a dramatic downstream problem for the interdependent professions that received no such equivalent stimulation. Stimulation of medical student numbers will place significant demands on the nursing and allied health professions (and health service infrastructure) once those graduates enter practice, particularly if those other professions are not simultaneously stimulated at the entry-point level. To prevent this type of maldistribution of health practitioner resources every policy and funding response for one professional group should be analysed against the implications from a whole-of-health workforce perspective. The creation of federally funded additional student places continues to be a common policy response. For example, Australian medical schools will see domestic graduates rise by 81% in the 7-year interval between 2005 and 2012 from 1348 to 2442. The rate of growth has been accompanied by predictions of serious downstream resource implications for postgraduate medical training (Joyce et al. 2007). The Australian Medical Association’s (AMA’s) submission to the Productivity Commission Review of the Health Workforce in 2005 recommended that all government spending decisions related to health policy should require a ‘health workforce impact statement’ (AMA 2005).

Within the Australian context, the thrust of health workforce planning and analysis has been consistently preoccupied with the medical profession, and cyclically concerned with the nursing profession (Australian Health Workforce Officials Committee 2003, Brooks et al. 2003, Hall 2005, Joyce et al. 2004). Despite their importance to the much vaunted ‘healthcare team’, workforce knowledge and research in relation to the allied health professions is rudimentary in terms of methodological approach, and lacking in comprehensiveness both in Australia and internationally (Australian Health Workforce Advisory Committee 2004).

The implementation of formal workforce advisory committees at the national level under the auspices of the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC) reflects this difference in focus between the different professional segments of the clinical health workforce. The Australian Medical Workforce Advisory Committee (AMWAC) was established in 1995 and has produced over 40 reports. The Australian Health Workforce Advisory Committee (AHWAC) was established in 2000 and has produced a dozen reports focused on the nursing profession. Responsibility for the allied health professions was added to AHWAC 4 years later with one major report produced. These committees were restructured in June 2006. The AHMAC established a series of principal committees to advise it on priority issues. The Australian Health Workforce Officials’ Committee (AHWOC) has been replaced by a new Health Workforce Principal Committee which will coordinate all of AHMAC’s workforce subcommittees. The various state and territory jurisdictions have produced a further range of reports that reflect a similar differential focus on these professions (AHWOC 2003). Given that the health professions work in an interdependent fashion in patient care settings, the primacy given to profession-centred rather than service-centred workforce planning models is increasingly recognised as ineffective for developing sustainable whole-of-workforce planning models.

New models of workforce planning

Despite improvement in modelling and underpinning data over the past decade, the outcomes with health workforce planning using profession-specific approaches have not been immune to the swinging pendulum effect of shortage-surplus-shortage (Hall 2005). On the supply side, it takes long periods of time to effect changes, given the length of time a new student entrant reaches full practice. Yet, labour markets for health professions can change very quickly, as has been observed from the recent sharp downturn in employment opportunities in the UK’s National Health Service (NHS). Aligning supply and demand, and monitoring the dynamic nature of labour markets is a difficult balancing act (Joyce et al. 2004).

The narrow focus on profession-specific workforce planning models has been responsible for a lack of integrated planning around major healthcare categories or disease profiles. Little work has been done on advancing alternative planning models but significant attention has been paid to refining existing approaches over the past decade. This overarching whole-of-profession work needs to continue, but complementary work at the level of services and patient populations needs to progress rapidly. A ‘planning how to plan’ process has been conducted recently at a national level on the prospective of a ‘models-of-care’ workforce planning model (AHWAC et al. 2005). Some pilot studies have been conducted by the states using variously defined ‘models-of-care’ or ‘models-of-service’ approaches. Potential advantages of a ‘models-of-care’ approach to workforce planning outlined by the ‘planning to plan’ process referred to above (AHWAC et al. 2005 p 8) included a greater emphasis on:

- a consumer focus

- alignment with service delivery plans

- multi-professional/multi-occupational approach capability

- a holistic approach to workforce issues.

- alignment with service delivery plans

One of the major planning difficulties underpinning a models-of-care approach is the lack of rigorous data for the array of professions that constitute the teams that deliver services in specific clinical settings. Such attempts at inter-professional planning will be impeded by the weak link in the chain, that is, by the low knowledge base about professions other than medicine and nursing (Boyce 2004). Buchan and Poz (2002), in their review of the evidence on skill mix and its role in health service planning, stressed that there was no skill mix algorithm that could be applied across contexts. Prescriptions about universal or ideal skill mixes are a misnomer. Skill-mix planning needs to start from the specific analysis of the patient population in question and their health needs in order to determine the type and mix of staffing required. This level of context-specificity points to the importance of localised workforce methodologies guided by national overarching policy instruments.

The preceding discussion focused on trying to capture the scope and nature of some of the policy problems that beset the capacity to undertake rigorous health workforce planning. The next section turns to examining the key recent policy responses that have been undertaken to respond to the growing policy panic surrounding the sustainability of the health workforce. The discussion centres on the development of the National Workforce Strategic Framework, the Productivity Commission review and the Council of Australian Governments’ (COAG) responses. From there we engage with some of the policy issues inherent in future strategies, such as professional substitution.

THE POLICY RESPONSE TO THE HEALTH WORKFORCE ‘CRISIS’

The challenge of health workforce problems has led to a series of high-level responses that have attempted to draw together a coordinated response across the many constituencies that have a stake in how the health workforce is reformed. Creating a policy infrastructure that has an overarching coordination focus to guide the developments at national, state, territory and regional levels is seen as a high priority. AHWOC, together with its subcommittees, was a forum for coordinating efforts across jurisdictions and developing a number of national strategic frameworks. Although the series of advisory committees managed under the auspices of AHMAC were reorganised in mid 2006, the work done by the AHWOC, AMWAC and AHWAC has been instrumental in building a body of work to provide the basis for a series of national plans with more rigorous policy analysis and development. AHMAC has also auspiced a number of working groups and taskforces to examine specific workforce issues. These include the:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workforce Working Group

- Care of Older Australians Working Group

- National Advisory Committee on Oral Health

- National Mental Health Working Group

- National Rural Health Policy Group

- Radiation Oncology Reform Implementation Committee.

- Care of Older Australians Working Group

The National Health Workforce Strategic Framework

The development of the National Health Workforce Strategic Framework (NHWSF) has been fundamental to creating a sustainable vision for health workforce policy. The framework, developed from consultation processes with stakeholders, was released by AHMAC in 2004 as a 10-year vision for health workforce priorities (Australian Health Ministers’ Conference 2004). The framework is structured around sets of strategies and guiding principles that will reinforce stakeholder collaboration and cohesion. The principles are the core of the framework and are ‘applicable to all stakeholders, and applied by all stakeholders to national health workforce policy. The strategies outline likely actions that will be required to implement the vision’ (Australian Health Ministers’ Conference 2004 p 5). For the seven principles that make up the NHWSF framework see Box 9.1.

BOX 9.1 SEVEN PRINCIPLES OF THE NATIONAL HEALTH WORKFORCE STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK

The final report of the Productivity Commission’s investigation of health workforce supported the NHWSF as a vehicle for coordination and recommended endorsement by COAG (Productivity Commission 2005). The commission did remark that it thought that principle number 1, with the goal of national self-sufficiency, was unduly restrictive. COAG agreed to reassess this principle. Current work on the NHWSF includes the development of key performance indicators against which the achievement of objectives can be measured.

The Productivity Commission: Australia’s health workforce

The Productivity Commission’s investigation of health workforce was an important policy opportunity in 2005–06. The commission, an independent body, conducts public inquiries and is the principal review and advisory agency on microeconomic policy and regulation for the Australian government. The terms of reference for the health workforce study focused on structural, institutional, distributional and regulatory factors arising from the health and education sectors (including post-tertiary and clinical education training) affecting the supply of, and demand for, health workers. The scope of the study was broad with ‘health workforce professionals’ defined as those trained from ‘the vocational education and training (VET) sector to medical specialists’ (Productivity Commission 2005 p iv). The public submissions to the commission were numerous and they provide a valuable ‘snapshot’ of the aspirations and defensive strategies of the professions when faced with the opportunity and threats of a major review.

A full analysis of the Productivity Commission report, and the subsequent acceptance, dilution, or rejection of recommendations by COAG, is beyond the scope of this chapter; however, there were some clear trends in the report (Box 9.2).

BOX 9.2 TRENDS IN THE PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION REPORT ON THE HEALTH WORKFORCE

Source: Productivity Commission 2005

The COAG meeting of July 2006 considered the commission’s report and was broadly in agreement with the thrust of recommendations, with two notable exceptions (COAG 2006). First, the national agency for health workforce improvement, which was to be the focus of workplace change and job innovation, was replaced with an advisory taskforce structure. And second, several of the recommendations on funding reforms to the Medicare Benefits Scheme (MBS) and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), particularly those to do with extended access by other professions, were rejected. COAG will receive a biennial report on the achievement of the reforms it has endorsed.

FUTURE POLICY DEVELOPMENT: WORKFORCE REFORM

For the remainder of the chapter our focus shifts to the first of four concluding comments in the commission’s report where it outlined its core proposals. ‘In essence the commission is proposing an integrated set of arrangements to drive reforms to scopes of practice, and job design more broadly, while maintaining safety and quality’ (Productivity Commission 2005 p xxxi). The commission recognised that reform to scopes of practice among the workforce, and substitution strategies, would be difficult. The commission cited the following indicative examples:

the introduction of nurse practitioners to Australia – a profession which has existed in some other countries for forty years – has been a drawn out process and is still encountering resistance from parts of the medical profession. Similarly, contested issues in relation to the roles of physiotherapists, radiographers and the various levels of the nursing professions seem likely to remain intractable in the absence of institutional reform.

Recalling the earlier citation of Hall’s (2005) comments about the inherently political nature of workforce planning and change, it is apparent that one profession’s aspiration for advancing role boundaries is another profession’s call to arms to defend incursion. Nancarrow and Borthwick’s (2005) study of workforce change and the strategies of diversification, specialisation and horizontal and vertical substitution noted that professional boundary changes are frequently described in language laden with combat and protectionism. The extensive field of the sociology of the professions has as its cornerstone the notion of occupational monopoly, the protection of formal bodies of knowledge, autonomy over work and an established hierarchy of professions in the division of labour (Abbott 1988, Freidson 2001). Freidson’s work on professional dominance and medical dominance theory in relation to the division of labour, which had its genesis in the 1960s, is still relevant as inter-professional jurisdictional disputes and struggles for control flare in a reform environment.

Although the boundaries of professions and task performance are permeable and interdependent, attempts at large-scale or systematic reordering of the hierarchy of control can predictably be met by opposition. This is so, particularly from the dominant professions, and most especially when a core task of a dominant profession is proposed for expansion to other professional groups (Fournier 2000, Nancarrow & Borthwick 2005). In the Australian context, the extension of prescribing rights to non-medical professions, autonomous access to the MBS and PBS by allied health and complementary or alternative professionals (Ch 10), the mainstreaming of nurse practitioners into independent urban settings, are all examples of the types of workforce ‘innovations’ which predictably spark anxiety among the dominant professions that traditionally had exclusive control of these territories.

How is the workforce to be reshaped in order to make the best use of existing competencies? While much heat is generated about who should undertake which new roles and what additional training, regulatory systems and safety and quality assurances are needed, the removal of politically structured impediments to utilising existing skills should also be a focus of ongoing attention. Removing the burdensome overhead of existing structural impediments will release workforce capacity and potentially influence exit from the professions. Almost 20 years ago, Willis’ text (1989) on medical dominance in Australia argued that existing skills were under-utilised and that in some contexts non-medical professionals were equally or better skilled in providing certain services to the public. Willis’ text (1989) treatise on the politics of skill (pp 217–25) provides a timely reminder of the benefit of looking back before rushing forward in the difficult arena of health workforce. Willis (1989 p 217) argued that ‘the most important political consequence of medical dominance is that it prevents the most effective utilisation of health resources in society. The health resources which are being under-utilised are primarily the skills of other workers’. Of equal importance to Willis’ observations is that many of the health professions replicate this same dominance and structural impediments in relation to the introduction of, or extended utilisation of, the skills of support workers. The Productivity Commission (2005 p 14) cited the guiding principle of the AHMAC submission that ‘… wherever possible, services should be delivered by staff with the most cost-effective training and qualifications to provide safe, quality care’.

At the heart of the current contestability about the shape of changing scopes of practice is the notion of professional substitution and how it is to be put into effect. The AMA has a clear vision of how it conceptualises substitution and its preferred model of delegation: ‘The AMA rejects task substitution as a positive reform but supports delegation to appropriately trained nursing and allied health colleagues’ (AMA 2005 p 5). The delegation model is further explained in a later statement as a ‘for and on behalf of’ framework in relation to the MBS (Yong 2006 p 27). The recent introduction of a new Medicare number for practice nurses working ‘for and on behalf of’ general practitioners is an example of the delegated model where the health professional providing the service (practice nurse) is not able to bill Medicare directly but has to do so in the name of the general practitioner.

This model of delegation is largely unknown in the allied health professions who have had rights as first contact practitioners to see clients without medical referral for 30 years (Galley 1977; Gardner & McCoppin 1995). Predictably, the allied health professions responded disapprovingly at the prospect of COAG rejecting the Productivity Commission’s proposals to allow other health professions direct access to Medicare; that is, billing directly in their own name as the service provider. The media release from the Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA) made the following comments by way of illustration of the contested and politicised nature of the policy content and its operational strategy:

The APA contends that governments buckling to the powerful medical lobby will maintain a closed-shop arrangement, to the detriment of the public interest … Of course, doctors’ groups are up in arms about extended scope reform and changes to referral arrangements, but the only explanation for their opposition must be blatant turf protection and self interest … [the Productivity Commission proposals] were likely to diminish the historical dominance of the medical profession on Australian health policy.(APA 2006)

COAG did subsequently reject the Productivity Commission proposals on this matter. Further engagement over the shape of substitution, delegation and independent practice models can be expected as a feature of inter-professional contests in workforce reform.

It is evident from the Productivity Commission’s report that underpinning its proposal for a stand-alone health workforce improvement agency was an appreciation of the need to undertake slow reform in a consultative manner with all stakeholders, particularly given the highly flammable nature of some proposals. There was wide support, but not unanimous support, from the professions for the stand-alone agency model. The potential for unintended consequences, financial ‘blow-outs’, threats to patient safety and a loss of public confidence arising from workforce reform were issues that required an active and dedicated management process if the under-utilisation of the existing workforce capacity was to be harnessed for the benefit of the public. In particular, the assessment of successful local innovations for application at a national level needs a stable forum for ongoing analysis from a whole-of-workforce perspective. It remains to be seen if COAG’s rejection of the recommended stand-alone health workforce improvement agency model in favour of a national taskforce to undertake project-based work is sufficiently powerful to achieve the type of change envisaged in much of the Productivity Commission report and the submissions it received from stakeholders.

The reform agenda for the health workforce will proceed and detailed action plans to implement COAG-endorsed proposals arising from the Productivity Commission process are underway. COAG has agreed to request the Australian government Treasurer to ask the Productivity Commission to undertake a further review of the health workforce by July 2011, thus ensuring another cycle of activity, aspirations and contestability.