Case 9 Osteoarthritis

Description of osteoarthritis

Definition

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease characterised by biochemical, cellular and structural changes to the articular cartilage, joint space and subchondral bone. The diarthrodial joints of the body, including the knees, hips and hands, are the most commonly affected. Depending on the aetiology of OA, the condition can be classified as either primary OA (idiopathic aetiology) or secondary OA. Secondary OA can be further defined as traumatic, metabolic, neuropathic, inflammatory or anatomic.1

Epidemiology

The prevalence of OA increases with advancing age. The prevalence rate of symptomatic OA in people under the age of 45 years, for example, is five per cent. Between the ages of 45 and 64 years, the prevalence rate increases to more than ten per cent, and over 75 years of age, to more than thirty per cent.2 In radiological prevalence surveys, the prevalence rate of OA is much higher (i.e. more than fifty per cent of people over 65 years of age),3 and in autopsy studies, even higher again (sixty to seventy per cent of people aged between 70 and 80 years).4 The disease is also more prevalent in women than men, particularly radiologically confirmed hand and knee OA, with the female:male ratio varying between 1.5 and 4.0 across studies.4

Aetiology and pathophysiology

Many risk factors are associated with the pathogenesis of OA. Increasing age, female sex, ethnicity, congenital joint abnormalities and family history are some of the major non-modifiable risk factors of OA. The modifiable risk factors include obesity, repetitive joint loading (e.g. repetitive squatting, kneeling, lifting), trauma (e.g. fractures, dislocations, joint surgery, meniscal or cruciate ligament tears), diet (e.g. low vitamin D, vitamin C and fruit intake, and elevated omega 6 fatty acid intake), and quadricep weakness.4 Several pathological conditions are also associated with the development of OA, including metabolic disease (e.g. haemochromatosis, hypothyroidism, Wilson’s disease), joint inflammation or infection, neuropathy (e.g. Charcot’s arthropathy) and cartilage disorders (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, chondrocalcinosis).5 All of these factors impair the integrity of joint tissue, causing direct damage to joint tissues, impairing repair processes or increasing joint susceptibility to injury.4

An initial insult to the joint stimulates chondrocyte activity, but at the same time triggers the release of inflammatory mediators from the synovium into the cartilage.5 While the chondrocytes attempt to repair the tissue by increasing the production of proteoglycans and collagen, they do so in opposition to the actions of the inflammatory mediators and proteolytic enzymes, which cause cartilage degradation. When the equilibrium between proteoglycan synthesis and degradation shifts towards net degradation, damage to articular cartilage occurs. Over time, subchondral bone becomes exposed, eburnated, sclerotic and stiff, which results in osseous infarction and subchondral cyst formation. In an attempt to protect the subchondral bone and to stabilise the joint, the body produces osteophytes.6 But instead of protecting the tissue, these spurs cause joint immobility and pain, and in some cases, synovitis. Eventually, joint mobility diminishes to such an extent that menisci fissure, supportive muscles weaken and periarticular tendons and ligaments become stressed, resulting in tendinitis and contractures.5

Clinical manifestations

OA is a progressive disease and, as such, may not present with any clinical manifestations in the early stages of development. Eventually, the client may begin to experience deep, aching arthralgia in one or several joints, particularly the hips, knees and hands. This pain is often aggravated by exercise, weight-bearing activity and changing weather, and alleviated with rest.7 As the disease progresses, joint stiffness develops, which is generally worse in the morning and after prolonged periods of rest. Further loss of articular cartilage results in reduced joint mobility, joint tenderness and crepitus. In the later stages of the disease, the client may experience joint instability and/or locking, muscle contractures and spasms. The structural changes to articular tissue, synovial thickening and joint effusion may also lead to joint enlargement.5 The pain and functional impairment associated with this disease also contribute to significant disability and reduced quality of life.2

Clinical case

69-year-old woman with bilateral knee osteoarthritis

Rapport

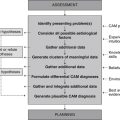

Adopt the practitioner strategies and behaviours highlighted in Table 2.1 (chapter 2) to improve client trust, communication and rapport, as well as the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the clinical assessment.

Medical history

Lifestyle history

Illicit drug use

| Diet and fluid intake | |

| Breakfast | Toasted white bread with marmalade, black tea. |

| Morning tea | Scones, or sweet biscuits or cake, black tea. |

| Lunch | Braised steak or beef sausages or roast chicken with boiled potato, cabbage and peas, battered butterfish with potato chips. |

| Afternoon tea | Sweet biscuits, black tea. |

| Dinner | Sandwich with white bread, ham and/or cheese. |

| Fluid intake | 2–3 cups of water a day, 2–3 cups of tea a day. |

| Food frequency | |

| Fruit | 0–1 serve daily |

| Vegetables | 2–3 serves daily |

| Dairy | 0–1 serve daily |

| Cereals | 6–7 serves daily |

| Red meat | 4 serves a week |

| Chicken | 3 serves a week |

| Fish | 1 serve a week |

| Takeaway/fast food | 0 times a week |

Quality and duration of sleep

Continuous sleep. Has difficulty falling asleep; average duration is 5–6 hours.

Diagnostics

Pathology tests

C-reactive protein (CRP)

CRP is a marker of inflammatory activity. The use of CRP in OA has not yet been established as there is a lack of consistent evidence to show that CRP is a valid and/or reliable marker of OA activity or a suitable predictor of OA incidence.8,9

Plasma/red cell fatty acid analysis

This test assesses the concentration of fatty acids within the plasma or erythrocyte, including omega 3, omega 6 and omega 9 polyunsaturated fatty acids, saturated fatty acids and trans fatty acids. Given that high dietary omega 6 fatty acid intake may be associated with a higher risk of developing bone marrow lesions in the knee,10 this test may help to determine whether increased omega 6 fatty acid consumption is a contributing factor in knee OA.

Radiology tests

Plain film X-rays and, less commonly, ultrasound, CT and MRI, are able to detect structural changes in the joint space, articular cartilage and subchondral bone. This is useful in providing radiographic confirmation of OA.11

Diagnosis

Planning

Goals

Expected outcomes

Based on the degree of improvement reported in clinical studies that have used CAM interventions for the management of OA,13–19 the following are anticipated.

Application

Diet

OA is an inflammatory disorder, thus it is conceivable that the consumption of foods and/or nutrients with demonstrable anti-inflammatory activity may play a role in the management of the disease. In a 10-year longitudinal cohort study, a positive association was observed between dietary intake of omega 6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of bone marrow lesions in the non-osteoarthritic knee joint,12 while an inverse association was reported between dietary intake of vitamin C and fruit, and bone marrow lesions.12 Neither of these nutrients was found to be associated with statistically significant changes in cartilage volume. In spite of these encouraging results, it is uncertain whether the increased consumption of fruit and foods containing vitamin C, and the reduced intake of omega 6 fatty acid-containing foods, is of any benefit in the secondary prevention of OA.

Dairy and tea consumption (Level III-3, Strength C, Direction +)

There is some evidence to suggest that the consumption of milk and tea could be of benefit to people with joint inflammation. A cross-sectional study of 655 individuals with symptomatic knee OA found lower rates of symptomatic OA among people consuming higher intakes of milk and tea.20 Whether different types of milk (e.g. cow versus goat) and tea (e.g. black versus green) confer different levels of benefit to people with knee OA is an area in need of further research.

Low-calorie diet (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Many risk factors are associated with the pathogenesis of OA. One risk factor that is amenable to dietary modification is obesity, which makes effective weight reduction an important goal in OA management. Evidence from two controlled clinical trials shows low-energy diets (with and without exercise) are significantly more effective than control diets at reducing body fat, but more importantly, are significantly more effective than controls in improving functional outcomes in obese individuals with OA.21,22 These improvements may be attributed to a reduction in joint load, as well as to a decrease in systemic inflammatory activity.23

Lifestyle

Relaxation therapy (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

The relaxation response can be induced by a number of behavioural therapies, such as progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery and autogenic training. Many RCTs have examined the effect of these therapies on pertinent OA outcomes. Results from three small trials have shown progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), hypnosis and guided imagery plus PMR to be significantly more effective than controls at improving OA-related pain,24,25 immobility,24 quality of life26 and analgesic use25 over 8–12 weeks; there was no statistically significant difference between hypnosis and PMR.25 Further research is needed to examine the comparative effectiveness of other relaxation therapies.

Tai chi (Level I, Strength B, Direction +)

Tai chi is an ancient Chinese therapy generally used as a meditative technique, soft martial art or form of physical exercise. In many ways, the physical and psychological benefits of tai chi are similar to those of exercise.27,28 Evidence from a systematic review of five RCTs and seven non-randomised controlled clinical trials is not convincing, with tai chi (for 6–24 weeks) failing to demonstrate consistent improvements in pain or physical function in people with OA.29 Findings from recent trials have been more favourable, with 12 weeks of Sun-style tai chi demonstrating significant symptomatic improvements in people with OA when compared with controls.15,18 The weight of the evidence seems to be in favour of tai chi, although further investigation is still warranted.

Yoga (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Yoga is an ancient Indian practice that integrates stretching, exercise, posture and breathing with meditation. Because aerobic exercise and stretching improve the symptoms of OA as well as the person’s functional capacity,30,31 it is possible that yoga could also offer some benefit to individuals suffering from this condition. Findings from two small trials lend support to this claim. An RCT of 25 patients with hand OA found yoga (once weekly for 8 weeks) to be significantly more effective than no treatment at reducing joint tenderness, finger range of motion and activity-induced hand pain.32 In an uncontrolled pilot study, yoga (once weekly for 8 weeks) was found to be effective at reducing Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain, WOMAC physical function, and Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale 2 (AIMS2) effect in 11 patients with knee OA.33 Given the methodological limitations of the latter study, and the small size of both trials, no firm conclusions can yet be made about the effectiveness of yoga for OA.

Nutritional supplementation

Chondroitin sulfate (Level I, Strength B, Direction o)

Chondroitin sulfate is a sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG), an important component of cartilage. In addition to this structural function, chondroitin sulfate serves to protect articular cartilage by reducing inflammatory and proteolytic enzyme activity, and by stimulating proteoglycan and hyaluronic acid synthesis.34 Not surprisingly, more than 22 controlled trials have examined the clinical efficacy of chondroitin sulfate in OA. A meta-analysis of 20 of these clinical trials (n = 3846) found chondroitin sulfate (administered orally or intramuscularly) to be more effective than controls at reducing joint pain.35 But due to the high degree of statistical heterogeneity of trials, the analysis was limited to three studies with large sample sizes and an intention-to-treat analysis (representing forty per cent of the total sample size). The revised analysis demonstrated that chondroitin sulfate was neither clinically nor statistically more effective than controls in improving the pain of OA. Larger trials that use more rigorous methodology are now needed in this area.

Glucosamine (Level I, Strength C, Direction + (for Rotta preparations))

Glucosamine is an amino sugar and an important precursor of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), a key constituent of articular cartilage. Glucosamine also inhibits proteolytic enzyme activity,36 reduces inflammation37 and stimulates proteoglycan synthesis.38 Even though these properties are fundamental to attenuating the pathogenesis of OA, the best available evidence is not conclusive. A Cochrane meta-analysis of 25 RCTs (n = 4963) found glucosamine (administered orally or parenterally) to be significantly superior to controls at improving OA pain and function using the Lequesne index, but non-superior to controls using WOMAC pain, function or stiffness subscales.39 When studies with inadequate allocation concealment were omitted from the analysis, glucosamine failed to show any benefit for pain. When glucosamine preparations were compared, those manufactured by Rotta Pharm were found to be significantly more effective than placebo at reducing pain and functional limitation. Non-Rotta preparations were no more effective than placebo at improving these outcomes; the increased severity of OA in these studies and the use of formulations other than glucosamine sulfate may have contributed to these results.

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) (Level I, Strength B, Direction o)

MSM is an organic sulfur compound that has been shown to downregulate nuclear factor kappaB signalling and to reduce tissue necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6, prostaglandin (PG) E2 and nitric oxide release in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine macrophages.40 This anti-inflammatory effect is not corroborated by data from human studies, with a meta-analysis of three double-blind, placebo controlled RCTs (including one for MSM and two for a similar compound, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)) concluding that DMSO/MSM supplementation for 3–12 weeks is neither statistically nor clinically more effective than placebo in reducing knee OA pain.41 Changes in mobility, physical function and stiffness were also inconsistent across the three studies.

Perna canaliculus (Level I, Strength C, Direction + (for pain only))

New Zealand green-lipped mussel (NZGLM) is a species of mollusc with high omega 3 fatty acid content. These fatty acids are believed to be responsible for the anti-inflammatory properties of the mussel. In animal and in vitro studies, NZGLM has been shown to inhibit cyclo-oxygenase (COX) activity, PGE2, TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12 and leukotriene B4 production, and swelling in several models of inflammation.42 In mechanistic studies, NZGLM supplementation failed to produce significant changes in blood levels of thromboxane B2, PGE2, IL-1β and TNF-α in human subjects after 6 weeks.43 Even so, a systematic review of three placebo-controlled RCTs reported significant improvements in OA pain after 6 months of NZGLM supplementation in two of three trials.44 Changes in joint mobility, physical and functional activity, and patient global assessment were not statistically significantly different between groups at 24 weeks, which suggests that more rigorously designed trials of NZGLM are needed.

S-adenosyl-L-methionine (Level I, Strength B, Direction +)

The coenzyme SAMe exhibits a range of activities considered beneficial to the management of OA. Specifically, SAMe demonstrates anti-inflammatory activity in vivo and a cartilage regenerating effect in vitro.45 According to a meta-analysis of 11 RCTs, these effects appear to translate into clinical practice. The review found orally administered SAMe (600–1200 mg daily, for 10–84 days) to be as effective as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) at reducing OA pain and functional limitation,46 but with comparatively fewer adverse effects. Yet in studies comparing SAMe to placebo, no statistically or clinically significant effects were observed for pain (n = 2 RCTs) or functional impairment (n = 3 RCTs).47 A major limitation of these studies is their short duration; hence, longer trials are required to ascertain if long-term supplementation of SAMe is a safe and effective treatment option for OA.

Vitamin C (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Serum CRP levels (a marker of acute inflammation) have been shown to be inversely related to vitamin C levels in healthy elderly men,48 suggesting that vitamin C may play a role in the regulation of inflammation and, possibly, in the management of OA. A double-blind, crossover RCT has shown that supplementation with calcium ascorbate (1 g) for 14 days was significantly more effective than placebo at improving pain (p = 0.008) and OA severity (p = 0.04) in 133 patients with radiographically verified symptomatic OA of the hip and/or knee.49 Investigation into the long-term effectiveness of vitamin C supplementation in OA, as well as the effect of different dosages, forms and chelating agents, is now required.

Vitamin E (Level II, Strength C, Direction o)

The tocopherols may attenuate the pathogenesis of OA by inhibiting the release of proinflammatory cytokines and by reducing monocyte adhesion to endothelial tissue.50 Data from four double-blind RCTs have not been consistent though. Results from two earlier and comparatively smaller trials found that supplementation with vitamin E (400–1200 IU daily, for 6–12 weeks) was significantly more effective than placebo at reducing knee pain, hip pain and analgesic use,51 and as effective as diclofenac (50 mg three times a day) at improving knee and/or hip pain, knee circumference and joint mobility.52 In contrast, results from two larger, more recent studies found that vitamin E supplementation (500 IU daily, for 6 months to 2 years) was no more effective than placebo at reducing knee OA symptoms or improving cartilage loss.53,54 While the weight of the evidence does not support the use of vitamin E in OA, there are some areas warranting further investigation, particularly the efficacy of higher dose vitamin E and the comparative efficacy of natural versus synthetic tocopherols.

Vitamin K (Level I, Strength C, Direction o)

One of the pathological signs of OA is cartilage calcification. Vitamin-K-dependent matrix gla protein (MGP) is responsible for opposing the mineralisation of cartilage,55 which could explain why people with lower plasma phylloquinone (vitamin K) levels have a higher risk of developing hand OA.56 It seems plausible, then, that vitamin K supplementation would reduce the risk or progression of OA. In a 3-year RCT of 378 otherwise healthy older adults, vitamin K (500 μg daily) plus multivitamin was found to be no more effective than control (multivitamin) at reducing hand OA prevalence, joint space narrowing and osteophyte formation.57 A subgroup analysis of the data did find that those deficient in vitamin K at baseline, who achieved sufficient concentrations of the vitamin at follow-up, demonstrated a forty-seven per cent reduction in joint space narrowing (p = 0.02). This finding should be interpreted with caution as subgroup analyses are not always reliable. The finding does highlight an important area for future research though.

Herbal medicine

Boswellia serrata (Level I, Strength B, Direction +)

Frankincense has long been used as an anti-inflammatory herb in Ayurvedic medicine and, more specifically, as a treatment for arthritis. Data from experimental studies support this action, with the boswellic acids in frankincense gum resin shown to inhibit 5-lipo-oxygenase (LOX) and COX activity, as well as the subsequent release of pro-inflammatory mediators.58 The traditional use of frankincense is further supported by findings from three clinical trials, including two well-designed double-blind placebo controlled trials, and one open label RCT. The oral administration of B. serrata resin extract (100–999 mg daily for 8–24 weeks) was found to be as effective as valdecoxib (an NSAID)19 and significantly more effective than placebo13,17 at improving OA knee pain and function. Whether these effects can be replicated in people with hip or hand OA is not yet clear.

Capsicum annuum (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Across the globe chilli is commonly used as a culinary herb, but in traditional herbal medicine it is used as a circulatory stimulant and decongestant. Capsaicin, the pungent principle of chilli, also exhibits analgesic activity by depleting stores of substance P from sensory neurons.59 When administered topically to OA joints (at 0.025–0.075 per cent concentration, four times a day for 4–12 weeks) capsaicin cream demonstrates statistically significant superiority to placebo in reducing joint pain and tenderness. These effects are consistently reported across five RCTs in a total sample of 430 people with OA.60–64

Harpagophytum procumbens (Level I, Strength B, Direction + (for pain only))

Devil’s claw is used in traditional South African medicine as a bitter tonic, vulnerary and analgesic for childbirth. In traditional Western herbal medicine, the plant is prescribed for the treatment of musculoskeletal complaints, specifically, inflammatory disorders such as arthritis.65 Even though devil’s claw has been shown in a number of experimental studies to modulate inflammatory activity by inhibiting COX, LOX, PGE2, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, reported effects are conflicting.66 Findings from a systematic review of four double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs in this area are a little more promising.67 In most studies, H. procumbens extract (960–2400 mg for 3–20 weeks) was found to be more effective than placebo at reducing OA pain. Individual studies also found devil’s claw to be significantly more effective than placebo at improving OA-associated mobility and stiffness, although these findings have yet to be replicated.

Pinus maritima (Level II, Strength B, Direction + (for some outcomes))

Under experimental conditions, French maritime pine bark extract (or pycnogenol) exhibits free radical scavenging67 and anti-inflammatory activity.69 The latter has been attributed to the inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB and the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1.68 Under RCT conditions, pycnogenol (100–150 mg for 3 months) statistically significantly improves total WOMAC score, walking distance and stiffness when compared with placebo in people with knee OA.69–71 People receiving pycnogenol also require less breakthrough analgesic medication than people receiving placebo. Changes in WOMAC pain subscore and WOMAC physical function subscore were not consistent across studies.

Zingiber officinale (Level I, Strength C, Direction o)

Ginger is used in many alternative systems of healing for its anti-inflammatory and circulatory stimulant properties. Under experimental conditions, ginger has been shown to inhibit the synthesis of PGE4 and nitric oxide in porcine chondrocytes72 and leukotriene B4 in vitro.73 While both of these effects may be useful in reducing the pain and inflammation of OA, this has yet to be demonstrated conclusively in humans. According to a recent systematic review, orally administered monopreparations of ginger (1.5–3.0 g per day) were found to be no more effective than placebo at reducing the severity of OA joint pain in two of three RCTs, and statistically significantly inferior to Ibuprofen in one of two trials. In relation to disability and functional capacity, ginger was found to be statistically significantly superior to placebo in one of two trials, and significantly inferior to Ibuprofen in one trial.74 Given the inconsistencies in these findings, no firm conclusions can yet be made about the effectiveness of ginger as a treatment for OA.

Other

Acupuncture (Level I, Strength B, Direction +)

Acupuncture originated in China more than 4000 years ago.75 This ancient therapy has long been used as a treatment for a number of acute and chronic complaints, including musculoskeletal disorders such as OA. The effectiveness of acupuncture in OA has also been extensively studied. Evidence from several systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate that acupuncture treatment (including manual and electro-acupuncture) is significantly more effective than sham acupuncture and usual care at reducing pain and improving function in people with OA of the hip, knee and thumb, but particularly the knee.14,76 Findings from more recent RCTs have, however, been inconsistent,77–79 which suggests that current systematic reviews need updating.

Aromatherapy (Level II, Strength B, Direction o)

Essential oils can generate a range of emotional, psychological and physiological effects, which may be helpful in the management of OA. Although no well-designed studies have investigated the effect of aromatherapy in people with OA, one double-blind RCT has tested the effectiveness of essential oil massage in 59 elderly patients with non-specific moderate to severe knee pain.80 Patients were randomised to three groups: essential oil massage (0.5 per cent orange oil and 1 per cent ginger oil in olive oil carrier), placebo massage (carrier oil only) or control (no massage). Patients received six 30–35 minute massage or control sessions over 3 weeks. Differences between groups for changes in knee pain intensity, stiffness level, physical function and quality of life were not statistically significant. Whether outcomes would be different in people with OA or by using different blends or higher concentrations of essential oils remains to be seen.

Chiropractic (Level II, Strength C, Direction +)

Chiropractic manipulation is generally prescribed for the treatment of nervous and musculoskeletal disorders, including OA. It was not until a few years ago that the effectiveness of this treatment in OA was rigorously examined. In a RCT published in 2006, 252 patients with lower back pain secondary to OA were randomly assigned to chiropractic care (including flexion or distraction and spinal manipulation) plus moist heat or moist heat only, for 20 treatment sessions over 6–10 weeks.81 Compared with the control group, chiropractic care and moist heat were found to be more effective at reducing back pain and increasing spinal ROM. Patients receiving chiropractic care also demonstrated greater improvements in several activities of daily living than people in the control group. Due to the likely introduction of observer bias from inadequate investigator blinding, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Homeopathy (Level I, Strength B, Direction +)

Homeopathy is a system of medicine that uses highly diluted and potentised remedies to influence the body’s vital force and restore homeostasis. As such, the therapy can be used to treat a wide range of acute and chronic conditions, including OA. Data from a 2001 systematic review of four RCTs (n = 406)16 and a 2002 controlled clinical trial (n = 80)82 have been promising, with four of the five studies showing homeopathic or combined allopathic-homeopathic medicines (administered intra-articularly, orally and topically) to be at least as effective as, if not superior to, conventional treatment at reducing pain and joint tenderness in people with OA. These results should be interpreted with caution though, as the study designs and treatments do not accurately reflect classical homeopathic practice.

Massage (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Massage is the systematic manipulation of soft tissues of the body. This tactile therapy may be particularly helpful for musculoskeletal disorders as it can help reduce anxiety, depression and pain by stimulating parasympathetic nervous system activity, as well as elevating serotonin and endorphin release.83 An RCT involving 68 adults with radiographically confirmed OA of the knee set out to test whether standard full-body Swedish massage (twice-weekly 1-hour sessions for 4 weeks, then once-weekly sessions for 4 weeks) was able to improve knee pain and function when compared to control (delayed intervention).84 The group receiving massage demonstrated greater improvements in pain, stiffness, physical functional disability and WOMAC global score than people in the control group. The difference between groups was statistically significant (p<0.008). While these outcomes are promising, further research is needed to improve the strength of the evidence.

Thermotherapy (Level I, Strength C, Direction + (for some outcomes))

Thermotherapy, or the application of heat or cold to an affected body part, is generally indicated in conditions characterised by pain, oedema and/or inflammation. Given that these manifestations typically present in OA, it is probable that thermotherapy may be of some benefit to people with this disorder. A systematic review of the literature identified three RCTs on thermotherapy and OA.85 Treatments included ice massage and cold or hot pack application. Ice massage (five 20-minute sessions per week for 2 weeks) was found to be significantly more effective than control at improving quadriceps strength, knee ROM and time to walk 15 metres (p<0.001). No benefit was detected for knee oedema. In terms of knee pain, the difference between ice pack application (three treatment sessions per week for 3 weeks) and control was only marginally significant (p = 0.06). When cold and hot pack applications were compared (20 minutes, 10 sessions), cold was found to be significantly superior at reducing knee oedema (p=0.04). While heat therapy was not found to be effective in this review, a more recent RCT indicates that moist heat rather than dry heat might be effective in arthritis. The study of 37 female patients with knee OA found that the continuous application of a heat or steam-generating sheet to the knee for 4 weeks was significantly more effective than a dry heat-generating sheet at improving total WOMAC score and gait ability score.86 Studies examining the comparative effectiveness of these treatments are now needed.

CAM prescription

Primary treatments

Secondary treatments

Referral

1. Sharma L., Kapoor D. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. In Moskowitz R.W., editor: Osteoarthritis: diagnosis and medical/surgical management, 4th ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

2. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Musculoskeletal conditions in Australia: a snapshot, 2004 (Cat. No. 4823.0.55.001). Canberra: ABS; 2006.

3. March L.M., Bagga H. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia. 2004;180:S6-10.

4. Arden N., Nevitt M.C. Osteoarthritis: epidemiology. Best Practice and Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2006;20(1):3-25.

5. Porter R., et al, editors. The Merck manual. Rahway: Merck Research Laboratories, 2008.

6. Freemont A.J. Pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. In: Arden N., editor. Osteoarthritis handbook. London: Taylor & Francis, 2006.

7. Lippincott Williams, Wilkins. Professional guide to diseases, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

8. Engstrom G., et al. C-reactive protein, metabolic syndrome and incidence of severe hip and knee osteoarthritis: a population-based cohort study. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2009;17(2):168-173.

9. Matsubara T., et al. Investigation of serum C-reactive protein in osteoarthritis of the knee. Central Japan Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology. 2006;49(2):289-290.

10. Wang Y., et al. Effect of fatty acids on bone marrow lesions and knee cartilage in healthy, middle-aged subjects without clinical knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(5):579-583.

11. Fischbach F.T., Dunning M.B. A manual of laboratory and diagnostic tests, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

12. Dingle J.T. The effects of NSAID on the matrix of human articular cartilages. Zeitschrift fur Rheumatologie. 1999;58(3):125-129.

13. Kimmatkar N., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of Boswellia serrata extract in treatment of osteoarthritis of knee: a randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(1):3-7.

14. Kwon Y.D., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2006;45(11):1331-1337.

15. Lee H.Y., Lee K.J. Effects of Tai Chi exercise in elderly with knee osteoarthritis. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2008;38(1):11-18.

16. Long L., Ernst E. Homeopathic remedies for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic review. British Homoeopathic Journal. 2001;90(1):37-43.

17. Sengupta K., et al. A double blind, randomized, placebo controlled study of the efficacy and safety of 5-Loxin(R) for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2008;10(4):R85.

18. Song R., et al. Effects of a Sun-style tai chi exercise on arthritic symptoms, motivation and the performance of health behaviors in women with osteoarthritis. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2007;37(2):249-256.

19. Sontakke S., et al. Open, randomized, controlled clinical trial of Boswellia serrata extract as compared to valdecoxib in osteoarthritis of knee. Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;39(1):27-29.

20. Kacar C., et al. The association of milk consumption with the occurrence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2004;22(4):473-476.

21. Christensen R., Astrup A., Bliddal H. Weight loss: the treatment of choice for knee osteoarthritis? A randomized trial. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2005;13(1):20-27.

22. Miller G.D., et al. Intensive weight loss program improves physical function in older obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Obesity. 2006;14(7):1219-1230.

23. Nicklas B.J., et al. Diet-induced weight loss, exercise, and chronic inflammation in older, obese adults: a randomized controlled clinical trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79(4):544-551.

24. Baird C.L., Sands L.P. A pilot study of the effectiveness of guided imagery with progressive muscle relaxation to reduce chronic pain and mobility difficulties of osteoarthritis. Pain Management Nursing. 2004;5(3):97-104.

25. Gay M.C., Philippot P., Luminet O. Differential effectiveness of psychological interventions for reducing osteoarthritis pain: a comparison of Erickson hypnosis and Jacobson relaxation. European Journal of Pain. 2002;6(1):1-16.

26. Baird C.L., Sands L.P. Effect of guided imagery with relaxation on health-related quality of life in older women with osteoarthritis. Research in Nursing and Health. 2006;29(5):442-451.

27. Frye B., et al. Tai chi and low impact exercise: effects on the physical functioning and psychological well-being of older people. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2007;26(5):433-453.

28. Jin P. Efficacy of Tai Chi, brisk walking, meditation, and reading in reducing mental and emotional stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1992;36(4):361-370.

29. Lee M.S., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Tai chi for osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Clinical Rheumatology. 2008;27(2):211-218.

30. Brosseau L., et al. Efficacy of aerobic exercises for osteoarthritis (part II): a meta-analysis. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2004;9(3):125-145.

31. Pelland L., et al. Efficacy of strengthening exercises for osteoarthritis (part I): a meta-analysis. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2004;9(2):77-108.

32. Garfinkel M.S., et al. Evaluation of a yoga based regimen for treatment of osteoarthritis of the hands. Journal of Rheumatology. 1994;21(12):2341-2343.

33. Kolasinski S.L., et al. Iyengar yoga for treating symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knees: a pilot study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2005;11(4):689-693.

34. Monfort J., et al. Biochemical basis of the effect of chondroitin sulfate on osteoarthritis articular tissues. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2007;67:735-740.

35. Reichenbach S., et al. Meta-analysis: chondroitin for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;146(8):580-590.

36. Bassleer C., Rovati L., Franchimont P. Stimulation of proteoglycan production by glucosamine sulfate in chondrocytes isolated from human osteoarthritic articular cartilage in vitro. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1998;6(6):427-434.

37. Largo R., et al. Glucosamine inhibits IL-1beta-induced NFkappaB activation in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11(4):290-298.

38. Uitterlinden E.J., et al. Glucosamine decreases expression of anabolic and catabolic genes in human osteoarthritic cartilage explants. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(3):250-257.

39. Towheed T., et al. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2): CD002946 (updated November 2008). 2005.

40. Kim Y.H., et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of methylsulfonylmethane on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in murine macrophages. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2009;32(4):651-656.

41. Brien S., Prescott P., Lewith G. Meta-analysis of the related nutritional supplements Dimethyl Sulfoxide and Methylsulfonylmethane in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, early release. 2009.

42. Doggrell S.A.. Lyprinol – is it a useful anti- inflammatory agent? Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, early release, 2009.

43. Murphy K.J., et al. Low dose supplementation with two different marine oils does not reduce pro-inflammatory eicosanoids and cytokines in vivo. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;15(3):418-424.

44. Brien S., et al. Systematic review of the nutritional supplement Perna Canaliculus (green-lipped mussel) in the treatment of osteoarthritis. QJM. 2008;101(3):167-179.

45. Blewett H.J.H. Exploring the mechanisms behind S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2008;48(5):458-463.

46. Soeken K.L., et al. Safety and efficacy of S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) for osteoarthritis. Journal of Family Practice. 2002;51(5):425-430.

47. Rutjes A.W.S., et al. S-Adenosylmethionine for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. (4): CD007321

48. Wannamethee S.G., et al. Associations of vitamin C status, fruit and vegetable intakes, and markers of inflammation and hemostasis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;83(3):567-574.

49. Jensen N.H. Reduced pain from osteoarthritis in hip joint or knee joint during treatment with calcium ascorbate. A randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over trial in general practice. Ugeskrift for Laeger. 2003;165(25):2563-2566.

50. Singh U., Devaraj S., Jialal I. Vitamin E, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2005;25:151-174.

51. Blankenhorn G. Clinical effectiveness of Spondyvit (vitamin E) in activated arthroses: a multicenter placebo-controlled double-blind study. Zeitschrift fur Orthopadie und ihre Grenzgebiete. 1986;124(3):340-343.

52. Scherak O., et al. Therapy with high doses of vitamin E in patients with osteoarthritis. Zeitschrift fur Rheumatologie. 1990;49(6):369-373.

53. Brand C., et al. Vitamin E is ineffective for symptomatic relief of knee osteoarthritis: a six month double blind, randomised, placebo controlled study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2001;60(10):946-949.

54. Wluka A.E., et al. Supplementary vitamin E does not affect the loss of cartilage volume in knee osteoarthritis: a 2 year double blind randomized placebo controlled study. Journal of Rheumatology. 2002;29(12):2585-2591.

55. Hale J.E., Fraser J.D., Price P.A. The identification of matrix Gla protein in cartilage. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263(12):5820-5824.

56. Neogi T., et al. Low vitamin K status is associated with osteoarthritis in the hand and knee. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(4):1255-1261.

57. Neogi T., et al. Vitamin K in hand osteoarthritis: results from a randomised clinical trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2008;67(11):1570-1573.

58. Ammon H.P. Boswellic acids in chronic inflammatory diseases. Planta Medica. 2006;72(12):1100-1116.

59. Cordell G.A., Araujo O.E. Capsaicin: identification, nomenclature, and pharmacotherapy. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 1993;27(3):330-336.

60. Altman R.D., et al. Capsaicin cream 0.025% as monotherapy for osteoarthritis: a double-blind study. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1994;23(Suppl 3):25-33.

61. Deal C.L., et al. Treatment of arthritis with topical capsaicin: a double-blind trial. Clinical Therapeutics. 1991;13(3):383-395.

62. McCarthy G.M., McCarty D.J. Effect of topical capsaicin in the therapy of painful osteoarthritis of the hands. Journal of Rheumatology. 1992;19(4):604-607.

63. McCleane G. The analgesic efficacy of topical capsaicin is enhanced by glyceryl trinitrate in painful osteoarthritis: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study. European Journal of Pain. 2000;4(4):355-360.

64. Schnitzer T., Morton C., Coker S. Topical capsaicin therapy for osteoarthritis pain: achieving a maintenance regimen. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1994;23(Suppl 3):34-40.

65. Bone K. A clinical guide to blending liquid herbs. St Louis: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

66. Brien S., Lewith G.T., McGregor G. Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens) as a treatment for osteoarthritis: a review of efficacy and safety. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2006;12(10):981-993.

67. Busserolles J., et al. In vivo antioxidant activity of procyanidin-rich extracts from grape seed and pine (Pinus maritima) bark in rats. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 2006;76(1):22-27.

68. Cho K.J., et al. Effect of bioflavonoids extracted from the bark of Pinus maritima on proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 production in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2000;168(1):64-71.

69. Belcaro G., et al. Pycnogenol may alleviate adverse effects in oncologic treatment. Panminerva Medica. 2008;50(3):227-234.

70. Cisar P., et al. Effect of pine bark extract (Pycnogenol) on symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. Phytotherapy Research. 2008;22(8):1087-1092.

71. Farid R., et al. Pycnogenol supplementation reduces pain and stiffness and improves physical function in adults with knee osteoarthritis. Nutrition Research. 2007;27(11):692-697.

72. Shen C.L., Hong K.J., Kim S.W. Comparative effects of ginger root (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) on the production of inflammatory mediators in normal and osteoarthrotic sow chondrocytes. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2005;8(2):149-153.

73. Blumenthal M. The ABC clinical guide to herbs. Austin: American Botanical Council; 2003.

74. Leach M.J., Kumar S. The clinical effectiveness of Ginger (Zingiber officinale) in adults with osteoarthritis. International Journal of Evidence-based Healthcare. 2008;6(3):311-320.

75. O’Brien K.A., Xue C.C. Acupuncture. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

76. White A., et al. The effectiveness of acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review. Acupuncture in Medicine. 2006;24(Suppl 1):40-48.

77. Foster N.E., et al. Acupuncture as an adjunct to exercise based physiotherapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2007;335(7617):436.

78. Jubb R.W., et al. A blinded randomised trial of acupuncture (manual and electroacupuncture) compared with a non-penetrating sham for the symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knee. Acupuncture in Medicine. 2008;26(2):69-78.

79. Tsang R.C., et al. Effects of acupuncture and sham acupuncture in addition to physiotherapy in patients undergoing bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2007;21(8):719-728.

80. Yip Y.B., Tam A.C. An experimental study on the effectiveness of massage with aromatic ginger and orange essential oil for moderate-to-severe knee pain among the elderly in Hong Kong. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2008;16(3):131-138.

81. Beyerman K.L., et al. Efficacy of treating low back pain and dysfunction secondary to osteoarthritis: chiropractic care compared with moist heat alone. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2006;29(2):107-114.

82. Maiko O.Y. Homoeopathic therapy of gonarthrosis with Zeel T. Biologische Medizin. 2002;31(2):68-74.

83. Moyer C.A., Rounds J., Hannum J.W. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(1):3-18.

84. Perlman A.I., et al. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(22):2533-2538.

85. Brosseau L., et al. Thermotherapy for treatment of osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003. (4): CD004522

86. Seto H., et al. Effect of heat- and steam-generating sheet on daily activities of living in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: randomized prospective study. Journal of Orthopaedic Science. 2008;13(3):187-191.