CHAPTER 9. Microvascular disease

Eugene Hughes

Diabetic retinopathy 196

Diabetic nephropathy 203

Diabetic neuropathy 206

Autonomic neuropathy 209

Erectile dysfunction 211

Conclusion 214

References 214

Diana is a 42-year-old married woman with type 1 diabetes. She has recently moved into the area and applies to join a new GP practice. She makes an appointment to see the GP as she has developed tingling and numbness in both her feet. She complains of a burning discomfort in her legs that is worse during the night and prevents her from sleeping.

Diana has had diabetes for almost 20 years and is on a twice-daily regime of a fixed mixture of insulin (soluble and isophane). She says that her diabetes is satisfactorily controlled and she never has any problems with hypoglycaemia. In conversation, it is clear that she rarely monitors her blood glucose and has not attended a diabetic clinic for more than 8 years. Her previous GP did not run a diabetic clinic and she has not received any screening for diabetic complications during this period of time. Diana’s GP finds that her blood glucose is measured at 14.6 mmol/L and her long-term control has been suboptimal indicated by an HbA1c of 10.2%. Diana states that she has never smoked and drinks only three units of alcohol per week.

On examination, Diana has reduced sensation to both light touch and pin-prick testing to mid-calf level in both legs. Her blood pressure is noted to be elevated at 165/95 mmHg; both her urea and creatinine are also elevated at 15.8 mmol/L and 270 micromol/L, respectively. Diana is referred to the local eye-screening clinic and advanced background retinopathy is confirmed.

Diana, after living with diabetes for nearly 20 years, has now developed some of the complications of diabetes namely hypertension, retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy. Diana’s hypertension would be managed according to the recommendations in Chapter 8.

INTRODCUTION

Microvascular disease occurs in people with both type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes. The hallmark of diabetic microvascular disease is microangiopathy (small vessel disease). This is the underlying abnormality that leads to retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy.

In microangiopathy, thickening of the capillary basement membrane leads to increased capillary permeability at an early stage. The development of microangiopathy is intricately linked with hyperglycaemia, and the duration of hyperglycaemia is an important determinant of microvascular disease. Individuals with type 1 diabetes can survive for many years without showing any signs of microvascular disease, particularly if they have optimal glycaemic control. Those with type 2 diabetes tend to be older at presentation and, even though they commonly have features of microvascular disease, it is ultimately macrovascular disease that leads to their untimely death. The exact biochemical mechanism of microvascular disease is not within the remit of this chapter; however, the central mechanism appears to relate to the sorbitol pathway. Hyperglycaemia leads to increased accumulation of sorbitol which does not easily cross cell membranes. The biochemical consequences of this directly affect the proteins in the vessel walls (Williams & Pickup 2004).

Diabetic microvascular disease is associated with the development of complications in people with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. This section discusses the following microvascular complications:

▪ diabetic retinopathy

▪ diabetic nephropathy

▪ diabetic neuropathy

▪ autonomic neuropathy

▪ erectile dysfunction (impotence).

For each of these complications, the prevalence, pathological features, screening, protocols for early referral and – where relevant – the implications of the national service framework for diabetes and the general medical services contract for primary care will be considered (Kenny 2004).

DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

THE FACTS

▪ Diabetes is the most common cause of blindness in people aged 30–69 years and the most common cause of blindness in the working population of developed countries (Cormack et al 2001, Icks et al 1997).

▪ 2% of the UK diabetes population are registered blind.

▪ The condition is treatable by laser photocoagulation.

FACTORS INFLUENCING THE DEVELOPMENT OF RETINOPATHY

▪ The duration of diabetes.

▪ The presence of hypertension.

▪ The development of chronic renal failure.

▪ The level of glycaemic control.

▪ Lifestyle factors including smoking and alcohol.

▪ Race as it is more common in certain ethnic groups.

It is clear from Diana’s case study that she meets three of these: diabetes for almost 20 years; hypertension and poor glycaemic control.

CLASSIFICATION

Diabetic retinopathy is graded into four main categories, depending on the extent of the disease seen on fundal examination.

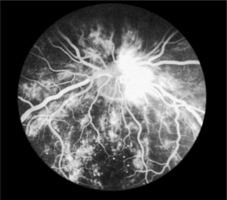

BACKGROUND RETINOPATHY

As capillaries close, the retina becomes underperfused with blood. Surrounding capillaries dilate in response to this and microaneurysms form. These tiny pin-head red dots are the first lesions to be seen in developing retinopathy. Dilated capillaries are usually leaky and proteinaceous material escapes forming creamy yellow exudates (hard exudates) on the retinal surface. Large blot haemorrhages tend to form at the interface of the well-perfused and ischaemic areas of the retina (Fig. 9.1).

|

| Fig. 9.1Fluorescein angiogram of the retina |

ADVANCED BACKGROUND RETINOPATHY

If extensive leakage from capillaries occurs around the macula, macular oedema develops. As the macula is involved with central vision, oedema of this area can markedly impair vision. The person will usually complain of blurring of vision, particularly central vision, which is used when reading. As more and more capillaries become occluded, large areas of the retina become ischaemic and cotton wool spots (or soft exudates) develop at sites of retinal microinfarction. The veins of the retina also begin to dilate. The veins form loops or show beading and reduplication. The presence of cotton wool spots and venous changes suggest that new vessel formation is imminent. Approximately one-third of people will develop new blood vessel formation within the next 2 years and progress to proliferative retinopathy. People with advanced background retinopathy should therefore be referred to an ophthalmology clinic. Diana was found to have this when she underwent screening.

PROLIFERATIVE RETINOPATHY

Ischaemic areas of the retina subsequently give rise to new blood vessel formation. These new vessels usually arise from veins in the retinal periphery or on the optic disc. At first they lie on the surface of the retina but eventually they grow forwards, attaching themselves to the posterior surface of the vitreous, which lies immediately in front of the retinal surface. As the vitreous detaches, it pulls on the new vessels, causing them to rupture and haemorrhage. Haemorrhaging into the vitreous causes sudden loss of vision as the blood prevents light reaching the retina behind. Vitreous haemorrhages usually clear gradually over a period of days or weeks with vision slowly recovering. Urgent referral to an ophthalmologist is recommended.

ADVANCED RETINOPATHY

Repeated vitreous haemorrhages stimulate fibrous tissue proliferation. Fibrous strands arising in relation to new vessels begin to contract and as this process gradually progresses, the retina become detached with resulting loss of vision.

COMPONENTS OF RETINOPATHY

▪ Small, round microaneurysms: dots.

▪ Medium-sized haemorrhages: blots.

▪ Hard exudates: irregular yellow lipid deposits.

▪ Cotton wool spots: white indistinct ischaemic areas.

▪ New vessels: fine tangled loops of vessels.

Background retinopathy

▪ Microaneurysms.

▪ Dot and blot haemorrhages.

▪ Hard exudates.

▪ Cotton wool spots.

Preproliferative retinopathy

▪ All of the above plus venous beading and looping and larger haemorrhages.

Proliferative retinopathy

▪ New vessels at the disc or in the periphery.

▪ Increased fibrosis.

▪ Retinal detachment.

Maculopathy

▪ Ischaemia or oedema of the macula area.

SCREENING AND PREVENTION

Prevention of diabetic blindness is possible in most people as long as treatment is initiated early. As the initial features of retinopathy are symptomless, screening is worthwhile and effective at detecting this and should be started from the age of 12 years (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) 55 2001). In Diana’s case, she had not had any eye screening for at least 8 years and it was fortunate that only background retinopathy was found.

Impaired vision is an early feature of maculopathy and can develop before any retinal changes are evident on ophthalmoscopic examination. A fall in visual acuity is therefore the first sign of serious maculopathy developing. By contrast, people with proliferative retinopathy will be unaware of any eye problem until a vitreous haemorrhage occurs, which causes a sudden loss of vision. By this stage retinopathy will be advanced and difficult to treat effectively. It is evident therefore that any screening programme must include both the routine measurement of visual acuity and fundoscopy or retinal photography (SIGN 2001).

VISUAL ACUITY

Distance vision is measured with a well illuminated Snellen chart at 6 metres. Each eye is tested separately, while the other eye is covered with a card. Visual acuity is quoted as the smallest letters that can be read. Thus, if a person can only read at 6 metres letters that should normally be read at 24 metres, visual acuity is recorded as 6/24. Normal vision is 6/6 but those with long sight and young people can often manage 6/5 or 6/4. Vision deteriorates with age and 6/9 vision is not necessarily abnormal in the elderly. If no letters can be read, the ability to count fingers (CF), identify hand movements (HM) or perceive light (PL), should be tested and recorded. Vision should be tested with the person wearing glasses if these are normally used for distance. If vision is impaired, the test should be repeated viewing the chart through a hole punched in a card (a pinhole). This partially corrects refractive errors. The best acuity measurement for each eye should be recorded.

Tests of reading ability using cards with varying sizes of script test central vision and are therefore particularly sensitive to macula changes.

FUNDAL EXAMINATION

Fundoscopy should be carried out only by doctors with training and experience of looking at the eyes of people with diabetes. For this reason, most GPs prefer to send individuals with diabetes to an ophthalmology clinic for retinal examination. In some areas of the UK, local opticians have been trained in assessing diabetic fundi and are used in screening programmes.

To obtain full and clear views of the retina, it is necessary for the pupils to be dilated by using mydriatic drops. Tropicamide (0.5% or 1%) one drop in each eye with phenylephrine hydrochloride 2.5% one drop in each eye (added after to maximise dilatation) are the most suitable agents because they act rapidly and wear off within 6 hours. There is little to be gained from reversing the dilatation using pilocarpine after the consultation. Drops are usually initiated by nursing staff, who should first check that the person does not suffer from glaucoma. The person should be advised previously that an eye examination will happen and warned that his or her vision may remain blurred and/or sensitive to light for up to 6 hours after the examination. Individuals might need to wear dark glasses and driving during this period is not recommended.

The examination should take place in a suitably darkened room using an ophthalmoscope with a fully charged battery providing adequate illumination.

In the UK a national retinal screening program is underway using non-mydriatic digital retinal cameras. Administrative call and recall procedures link diabetes registers to the precess where trained screeners and graders offer a quality assured service.

RETINAL PHOTOGRAPHY

Retinal screening by ophthalmoscopy should be considered the bare minimum standard of screening. Retinal photography as part of a local or regional scheme should be accessible to most people with diabetes. The National Service Frameworks for Diabetes recommended that retinal screening programmes be put into place throughout the UK by 2006. Leese et al (2005) found that robust screening resulted in more appropriate referrals to ophthalmologists. Digital retinopathy with assessment and a grading is likely to become the gold standard in most areas. This has the advantage of being able to store and compare images with successive assessments. Digital photographs can also be used for telemedicine in remote and rural areas where there is robust quality assurance it is practical and advantageous (Schneider et al 2005). Criteria for referral to ophthalmologist are detailed in Box 9.1.

Box 9.1

Criteria for referral to an ophthalmologist

Routine referral

▪ Cataract

▪ Non-proliferative retinopathy

Early referral

▪ Preproliferative changes

▪ Retinal haemorrhages and perimacular hard excudates

▪ Decreasing visual acuity (because this might indicate maculopathy)

Urgent referral

▪ New vessels

▪ Rubeosis iridis

Immediate referral

▪ Vitreous haemorrhage

▪ Neovascular glaucoma

▪ Advanced diabetic eye disease including retinal detachment

GENERAL MEASURES FOR PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

As for all microvascular and macrovascular complications, improving clinical and lifestyle factors will help prevent the onset and deterioration of diabetes complications (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) 1993):

▪ tight glycaemic control

▪ tight blood pressure control

▪ tight lipid control

▪ smoking cessation.

SPECIFIC TREATMENT

Photocoagulation

Laser photocoagulation is particularly effective in preventing visual loss due to new vessel formation. To be effective it must be given early. In 90% of people the new vessels disappear or become insignificant. In ischaemic maculopathy, treatment is less effective. However, in clinically significant macula oedema, laser treatment has been show to be beneficial (SIGN 2001). For proliferative retinopathy, photocoagulation is applied to a larger area of the retina (pan retinal photocoagulation). This can involve between 1500 and 7000 separate burns and can be performed over several sessions of outpatient treatment, following the application of topical local anaesthetic drops. Some people experience mild discomfort with this procedure. If severe discomfort is experienced, retrobulbar local anaesthetic can be given. The underlying principle of photocoagulation is that it halts deterioration; it might not lead to improved visual acuity.

WHAT IT ALL MEANS TO THE INDIVIDUAL WITH DIABETES

Whereas healthcare professionals seek to detect and treat diabetic retinopathy at various stages, the reality of diabetic eye disease occurs when the persons’ visual acuity starts to deteriorate. This has an increased significance for self-management because good visual acuity is required to undertake self blood glucose monitoring, inject insulin and to inspect a person’s own feet. A number of services within the UK are available for people with poor visual acuity (Box 9.2):

Box 9.2

useful address

▪ Action for Blind People: 14–16 Verney Road, London SE16 3DX tel: 0207 7328771

▪ Partially Sighted Society: Queens Road, Doncaster DN1 2NX tel: 01302 323132

▪ Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB), 224 Great Portland Street, London W1N 6AA tel: 0207 3881266

▪ Talking books are available from the Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB).

▪ British Talking Book Service for the Blind.

▪ Royal National Library for the Blind.

▪ Talking newspapers, available from the Talking Newspaper Association.

▪ Library services: most libraries have large print books and tapes.

▪ Residential establishments, courses, holiday homes and caravans for the blind organised by the RNIB.

▪ Talking meter (see Chapter 7).

BLIND REGISTRATION

In the UK, blind registration is available for people with a visual acuity of less than 3/60 in their better eye. Individuals with a visual acuity of less than 6/60 in the better eye can be registered as partially sighted. These processes are undertaken by a consultant ophthalmologist.

DIABETIC NEPHROPATHY

THE FACTS

▪ The natural history of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes is different.

▪ About 30% of people with type 1 diabetes will develop nephropathy.

▪ About 10% of people with type 2 diabetes will develop nephropathy.

▪ Many people with diabetes die from macrovascular disease before the nephropathy progresses.

▪ Nephropathy is associated with an increased risk of retinopathy and an increased risk of coronary artery disease (Gross et al 2005). The incidence of nephropathy in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes is falling due to earlier detection and improved methods of treatment for glycaemic control and blood pressure (DCCT 1993, SIGN 2001, UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) 33 1998).

MICROALBUMINURIA

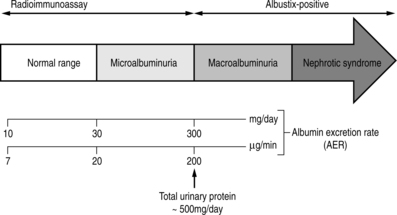

Microalbuminuria precedes the development of nephropathy and is characterised by an albumin excretion rate of 30–300 mg/day. Microalbuminuria is detectable by radioimmunoassay and by highly sensitive urine dipstick tests such as Micral Test©. Alternatively, a urinary albumin : creatinine ratio (ACR) can be measured from an early-morning specimen.

Diabetic nephropathy is characterised by persistent albuminuria (an albumin excretion rate greater than 300 mg per 24 hours). This is the equivalent of a 24 hour urinary protein excretion of 500 mg (Fig. 9.2).

|

| Fig. 9.2Normoalbuminuria, microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria.Reproduced, with thanks, from Williams & Pickup (1998)Williams & Pickup |

Type 1 diabetes

In type 1 diabetes, it is unusual to detect microalbuminuria within 5 years of diagnosis (Gross et al 2005). Thereafter, the incidence increases such that after 15 years from diagnosis, 50–60% of people will have microalbuminuria; the incidence is higher in men. About 35% of people will progress to nephropathy.

Type 2 diabetes

Many people with type 2 diabetes have microalbuminuria or even proteinuria at diagnosis and this is associated with the co-existence of hypertension. People of Afro-Caribbean and Asian descent have a higher prevalence of nephropathy (Wu et al 2005); 50% of people who develop end-stage renal disease in Britain have type 2 diabetes.

As nephropathy progresses, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) progressively decreases. Serum creatinine levels start to rise and once these exceed 20 μmol/L progression to end-stage renal failure is relentless. Blood pressure also rises progressively. In many people with type 2 diabetes, the blood pressure is already elevated at the time that albuminuria is detected.

Eric was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at the age of 35. He takes 850 mg metformin twice a day. Five years later at his annual review for complication screening, he was found to be hypertensive with a blood pressure of 160/95 mmHg; his glycated haemoglobin had deteriorated to 9%. His lipid profile had also deteriorated, showing an increased LDL and decreased HDL. He complains of pins and needles and a burning sensation in both feet that was worse at night. His biochemistry profile showed a rise in serum creatinine but still within the normal range. His glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was decreasing and he had a persistent albuminuria greater than 300 mg in 24 hours. His ACR measured at 25 mg/mmol.

Eric had a previous history of background retinopathy and, as is often the case with renal complications, it is very possible that his diabetic eye disease has also progressed. Urgent screening for diabetic eye disease would be recommended if this was not already due.

CLINICAL SIGNS OF NEPHROPATHY

There are few clinical signs in the early stages of nephropathy. Anaemia develops as the disease progresses and in the later stages oedema and breathlessness will develop. People with type 2 diabetes have often developed severe cardiovascular disease by this point. Neuropathic and ischaemic foot ulceration is also more common in those people with nephropathy and hyperlipidaemia commonly co-exists (see Chapter 10).

SCREENING AND EARLY DETECTION

Urinary screening for microalbuminuria and proteinuria should be performed in all people with diabetes at least annually. Those with type 1 diabetes should have this done from 5 years after diagnosis (Gross et al 2005). In those with type 2 diabetes, it should be done from diagnosis (Gross et al 2005). Screening elderly people is problematic because errors are common due to urinary tract infections and prostate disease, and also because the benefits of screening and early treatment take several years to accrue. If the individual is found to have albuminuria on two separate early-morning urine specimens, further investigation should be undertaken to exclude other renal disease. These investigations would include a midstream specimen of urine (MSU), possible renal ultrasonography and a 24-hour urine protein collection.

If the individual’s urinalysis is albustix negative, screening for microalbuminuria should be undertaken. This can be done by microalbuminuria testing strips or by ACR. The ACR value should be less than 2.5 mg/mmol in men and less than 3.5 mg/mmol in women. If the screen is positive, an MSU test should be undertaken. If this is negative, timed overnight urine collections should be performed. It might be necessary to repeat this investigation on two or three occasions.

Confounding factors

The following can cause false-positive results in microalbuminuria testing:

▪ urinary tract infection

▪ exercise

▪ prostatic disease

▪ heart failure

▪ day-to-day variation.

MANAGEMENT

Eric’s long-term health is seriously under threat not only from microvascular complications but also from macrovascular complications. Several issues need to be addressed:

▪ In Eric’s situation the first parameter to address would be to encourage him to improve his glycaemic control. The UKPDS 33 (1998) and the DCCT (1993) both showed that tight glycaemic control in people with diabetes reduces the progression of renal disease. Eric might require a change or addition to his treatment regimen. Depending on the extent of his nephropathy, he might need to reduce or stop metformin.

▪ Eric’s elevated blood pressure requires aggressive management. This can reduce the progression from microalbuminuria through albuminuria to end-stage renal failure. His blood pressure should be reduced to 135/85 mmHg. Diuretics, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers have all shown to be effective in managing hypertension associated with diabetic renal disease. However, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE) and angiotensin-II receptor antagonists have been shown to have an extra effect on progression of microalbuminuria over and above their antihypertensive effect. Those with type 1 diabetes with microalbuminuria should be started on an ACE inhibitor regardless of the level of blood pressure (SIGN 2001). Those with type 2 diabetes with microalbuminuria should also be started on an ACE inhibitor with the aim of reducing blood pressure to 130/80 or 120/70 mmHg in the face of established disease (see Chapter 8 for further details on blood pressure management).

▪ Eric also requires lipid-lowering agents. People with diabetic renal disease will almost certainly have dyslipidaemia and require aggressive treatment to reduce cardiovascular risk. This is addressed in Chapter 8.

▪ There is minimal evidence that the decline in GFR is reduced by limiting protein intake (Williams & Pickup 2004).

▪ If appropriate, Eric would be referred to discuss smoking cessation (see Chapter 11).

▪ Low-dose aspirin therapy should be started.

These measures are advocated mainly in relation to their role in the management of cardiovascular risk, which in this case, is high.

RENAL FAILURE

Those with progressing diabetic renal disease should be referred to a nephrologist once the serum creatinine exceeds 150 μmol/L (SIGN 2001).

Options for managing end stage renal failure include:

▪ Haemodialysis.

▪ Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD).

▪ Renal transplantation: the 5-year survival rate after renal transplantation in people with type 1 diabetes has recently been reported as being better following a combined pancreas and kidney transplantation (82%) than after kidney transplantation alone (60%) (Orsenigo et al 2004).

▪ Palliative care.

DIABETIC NEUROPATHY

THE FACTS

▪ Eric displays typical symptoms of a painful peripheral neuropathy and will need treatment for this debilitating problem. Around 25% of persons with diabetes however have an asymptomatic neuropathy and are thus prone to foot problems (see Chapter 10).

▪ Neuropathy is rare in people newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes but is often present at the time of diagnosis in people with type 2 diabetes. However, there might be symptoms of painful peripheral neuritis in both type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes. These can resolve in a matter of weeks with improved glycaemic control.

▪ Neuropathy can seriously affect mental health in people with diabetes, and depression and anxiety are prevalent (Vileikyte et al 2005).

▪ Acute neuropathies can be related to poor glycaemic control and can respond well to improvement. Chronic neuropathies are more difficult to manage and treatment can be difficult.

▪ Whereas neuropathy is more often evident in the lower limbs, it can affect any nerve in the body. Hence there are a variety of neuropathies including cranial nerve palsies, foot drop, amyotrophy and autonomic neuropathy.

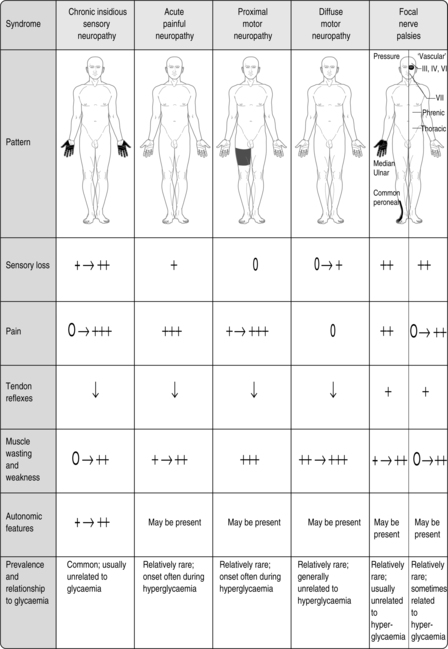

CLASSIFICATION AND OUTCOMES

Chronic distal sensory neuropathy

This is the most common form of neuropathy in people with diabetes. The onset is insidious, usually with numbness starting in the toes and soles of the feet and spreading proximally in a symmetrical ‘stocking’ distribution. Clinical examination will reveal reduced sensitivity to fine touch, vibration and temperature sensation. The ankle reflexes are often absent.

The significance of this condition is that the individual with reduced sensation is more likely to experience undetected injury from ill fitting shoes, foreign objects in shoes and from burns due to hot water bottles and electric fires. This predisposes the individual to foot ulceration and its appalling consequences. For this reason people who are found to have distal sensory loss should be referred to a foot clinic for appropriate education and management (see Chapter 10).

Painful neuropathy

In this situation, the person can complain of a variety of sensory symptoms of a severe nature, usually in the lower aspects of the legs. The pain might be burning, shooting or tingling and is characteristically worse at nights when in contact with bed clothing. It is usually associated with poor glycaemic control and rectification of this or stabilisation of blood glucose profiles leads to recovery over several months or even up to 2 years.

Various treatments are available. It is essential to improve diabetic control. For quality of life, it is important to give adequate pain control, predominantly through membrane stabilisation drugs (Barbano et al 2003) (Box 9.3).

Box 9.3

Treatment for painful neuropathy

▪ Tricyclic antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs have been shown to be beneficial, particularly gabapentin, carbamazepine and phenytoin

▪ Capsaicin cream 0.075% applied topically can have some benefit in

▪ painful neuropathy but involves prolonged treatment and might initially cause a burning sensation when applied

▪ A role for aldose reductase inhibitors has been postulated

Diabetic amyotrophy

This painful condition usually affects people with type 2 diabetes over the age of 50 (Simmons & Feldman 2002). Affected individuals usually report severe pain, normally in the upper legs, that has developed over weeks and months. There is also severe muscle wasting of the quadriceps muscles and people might struggle to rise from a chair unaided. The upper limbs can also be affected. The individual might report some weight loss.

This condition appears to resolve without active treatment about 2–9 months after the onset (Simmons & Feldman 2002). People with this would be treated symptomatically for pain and physiologically for blood glucose control. Most people with diabetic amyotrophy experience resolution of their pain and some motor recovery of their muscles; however, this latter aspect might not be complete. Even after 1–2 years, people may still struggle with daily functions like climbing stairs or getting in and out of bed. This condition is rare and members of the primary healthcare team will not normally be asked to manage this condition but need to be aware of the affects it has on the lives of individuals.

Focal neuropathies

▪ Carpal tunnel syndrome.

▪ Third cranial nerve palsy.

▪ Sixth cranial nerve palsy.

▪ Peripheral mononeuropathies, such as common peroneal nerve.

Some of these neuropathies are due to nerve entrapment or pressure or to vascular damage, i.e. they are not related to the level of glycaemic control, and might respond to surgical intervention. Some of these neuropathies resolve spontaneously (Fig. 9.3).

|

| Fig. 9.3Clinical patterns of diabetic peripheral neuropathy.Reproduced, with thanks, from Williams & Pickup (1998)Williams & Pickup |

ASSESSMENT

As neuropathy can be insidious, neurological examination is mandatory at diagnosis and at least annually thereafter. Simple clinical examination can be undertaken (see Chapter 10).

REFERRAL

Everyone presenting with newly diagnosed neuropathy affecting their feet should be referred to a podiatrist for specialist advice (Chapter 10). People who appear not to receive relief from normal treatment might benefit from referral to a pain clinic.

THE FACTS

Autonomic neuropathy is relatively uncommon. It is due to damage to the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves and is usually associated with peripheral neuropathy. The symptoms that people present with can be intermittent.

Simple tests for autonomic neuropathy can be undertaken in a community care setting:

▪ lying and standing blood pressure: record lying blood pressure then stand the person up and record blood pressure 2 minutes later; a fall of more than 30 mmHg is expected

▪ pupillary reflexes: these are often abnormal

▪ heart rate variation after deep breathing: this would normally be greater than 15 beats per minute.

More complicated assessment involves the use of the Valsalva manoeuvre.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND TREATMENT

Postural hypotension

Postural hypotension can cause dizziness and faintness, particularly on rising from sitting or lying. The fall in blood pressure is usually > 30 mmHg. Assessment involves reviewing medication, as certain drugs can aggravate the hypotension, including antidepressants and diuretics. Elevation of the head of the bed when sleeping can be helpful, elastic support stockings can also be of benefit. Therapeutic measures include the use of fludrocortisone.

Gastroparesis

This is due to delayed gastric emptying and might be associated with vomiting. Treatment options include metoclopramide and domperidone. Erythromycin can increase gastric emptying but is of limited use. In extreme situations surgery is necessary.

Diarrhoea and constipation

Diarrhoea is one of the more common autonomic disturbances. The individual complains of explosive diarrhoea, which is often worse at night. Other causes of diarrhoea should be excluded by investigation. Treatment is with loperamide or codeine phosphate.

Some people complain of constipation, which can be managed by bulking agents and laxatives.

Urinary tract

People can suffer from urinary retention and overflow incontinence. Treatment is by regular toileting but, ultimately, self-catheterisation could be required.

This occurs when eating and can lead to excessive sweat production from the face, neck and chest. Treatment is by anticholinergic drugs or glycopyrronium powder.

Anhidrosis

There can be absence of sweating, particularly on the lower limbs, which poses an additional risk factor for the development of diabetic foot conditions. Emollient creams are recommended.

ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION

Erectile dysfunction is defined as the inability to achieve or maintain an erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual intercourse. Of the numerous clinical problems affecting persons with diabetes mellitus, erectile failure is one of the most common but is probably the least talked about – by the person, his partner and the attending healthcare professionals.

Fred is 64 years old and has had type 2 diabetes for 15 years. He took early retirement from his job 9 years ago and lives a full life. He and his wife have been married for 40 years and have two children and five grandchildren, of whom they are very proud. Fred is a local councillor and considered to be a pillar in the community. He is active in fighting for play areas for children and traffic-calming measures. He frequently writes articles for the local paper on issues affecting the community.

Fred comes to see the GP and appears to be very awkward in his conversation. He eventually admits that he has ‘men’s problems’. After encouragement to discuss his problem, Fred admits that he has impotence, which has occurred fairly recently. He feels it is beginning to cause a strain between himself and his wife and it was at his wife’s insistence that he attended the GP.

Healthcare professionals in such situations must always be alert to problems of a sexual nature and ensure that they adopt an accepting, open approach to encourage the person to discuss their problem. Fred would be reassured of the confidential nature of any appointment with a healthcare professional and advised that there are several options to explore. Fred would first be informed of the facts.

▪ Erectile dysfunction is common: it can affect up to 40% of men with diabetes.

▪ The aetiology can be complex, involving many physical factors.

▪ Other diseases interfere with physiological mechanisms (Saenz de Tejada et al 2005).

▪ Psychological factors in men with diabetes should not be ignored.

▪ The parasympathetic nervous system mediates erection; the sympathetic nervous system mediates ejaculation.

▪ Erectile dysfunction is independently associated with cardiovascular disease, increasing fasting glucose levels, diabetes and future coronary risk (Grover et al 2006).

CAUSES OF ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION

Common

▪ Diabetic neuropathy.

▪ Peripheral vascular disease.

▪ Drugs such as antihypertensives, diuretics and anti-depressants.

▪ Psychological factors.

▪ Alcohol.

Less commonly

▪ Trauma.

▪ Penile abnormalities.

▪ Endocrine causes such as hypogonadism.

ASSESSMENT

The first stage in any clinical situation is to undertake a detailed assessment. Fred’s assessment would include a clear history to determine whether there is a lack of erections or whether the problem is more complicated and includes disorders of libido or ejaculation. The absence of nocturnal or morning erections, together with a gradual onset of symptoms, favours an organic cause.

A physical examination would be undertaken to detect signs of peripheral and autonomic neuropathy, vascular disease, penile disorders and endocrine disturbance. Investigations should include an assessment of overall glycaemic control, thyroid function tests, liver function tests, serum lipids and, if appropriate, serum testosterone, prolactin and ferratin.

Psychological aspects of erectile dysfunction must be considered. These would include anxiety about sexual performance, psychological affects of trauma or abuse and depression. Relationship problems can also cause erectile dysfunction. Eliciting facts around this require the healthcare professional to be sensitive to Fred’s feelings and it might take a few visits before a full picture of any psychological trauma emerges.

MANAGEMENT

The management of erectile dysfunction should always include sympathetic enquiry and counselling. The introduction of oral treatments for this problem prompted a lot of media interest, and as a result, individuals might be more comfortable in discussing their problems. It is often helpful to invite the partner to be present and in this instance Fred and his wife were asked to attend all appointments. There is now a wealth of information in the form of leaflets, tapes and videos, which can be helpful and is available from pharmaceutical companies. Diabetes UK offers advice and information from its website (www.diabetes.org.uk).

Oral therapies

The management of erectile dysfunction has been revolutionised by the introduction of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors. These drugs prevent the degradation of the smooth muscle relaxant cyclic GMP, thereby increasing blood flow to the penis. Sildenafil was the first to be introduced and one study on 188 men with type 1 diabetes demonstrated that it was an effective treatment and well tolerated (Stuckey et al 2003). Tadalafil and vardenafil are also now available on the NHS in the UK. They should be taken 30–60 minutes before sexual activity and work only in the presence of sexual stimulation. Tadalafil claims that the efficacy can persist for up to 36 hours. These drugs are contraindicated in the presence of cardiac disease, recent myocardial infarction and unstable angina. They should not be taken with nitrates.

Apomorphine hydrochloride is a selective dopamine agonist. Taken sublingually, it produces an erection within 20 minutes.

Transurethral alprostadil

Transurethral alprostadil is prostaglandin E1 that is introduced into the urethra by a special device.

Intracavernosal alprostadil

Individuals are taught how to self-inject alprostadil into the base of the penis. This is used less frequently now that oral therapies are available.

Vacuum devices

A cylinder fitted over the penis enables a vacuum to be created, which results in penis engorgement. The erection is maintained by a construction ring at the base of the penis.

These semi-rigid or inflatable devices can be implanted in the penis when other treatments have failed.

Thus Fred and his wife could be reassured by the range of treatment options and encouraged to try appropriate ones until they found one that was mutually satisfying.

Microvascular disease is a major cause of morbidity in people with diabetes. Screening plays an important part in the early detection of clinical changes as often, by the time people complain of clinical signs and symptoms, irreparable damage has been done. Early detection can ensure that the appropriate treatment is initiated to reduce or delay the onset of microvascular disease in people with diabetes.

REFERENCES

R Barbano, S Hart-Gouleau, J Pennella-Vaughan, RH Dworkin, Pharmacotherapy of painful diabetic neuropathy, Current Pain & Headache Reports 7 (3) (2003) 169–177.

TG Cormack, B Grant, MJ Macdonald, et al., Incidence of blindness due to diabetic eye disease in Fife 1990–9, British Journal of Ophthalmology 85 (3) (2001) 354–356.

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) Research Group, The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, New England Journal of Medicine 329 (1993) 977–986.

JL Gross, MJ de Azevedo, SP Silveiro, et al., Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment, Diabetes Care 28 (1) (2005) 164–176.

SA Grover, I Lowensteyn, M Kaouache, et al., The prevalence of erectile dysfunction in the primary care setting: importance of risk factors for diabetes and vascular disease, Archives of Internal Medicine 166 (2) (2006) 213–219.

A Icks, C Trautner, B Haastert, et al., Blindness due to diabetes: population-based age- and sex-specific incidence rates, Diabetic Medicine 14 (7) (1997) 571–575.

C Kenny, Primary diabetes care: yesterday, today and tomorrow, Practical Diabetes International 21 (2) (2004) 65–68.

GP Leese, AD Morris, K Swaminathan, et al., Implementation of national diabetes retinal screening programme is associated with a lower proportion of patients referred to ophthalmology, Diabetic Medicine 22 (8) (2005) 1112–1115.

E Orsenigo, P Fiorina, M Cristallo, et al., Long-term survival after kidney and kidney-pancreas transplantation in diabetic patients, Transplantation Proceedings 36 (4) (2004) 1072–1075.

I Saenz de Tejada, J Angulo, S Cellek, et al., Pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction. Consensus Development Conference, Journal of Sexual Medicine 2 (1) (2005) 26–39 .

S Schneider, SJ Aldington, EM Kohner, et al., Quality assurance for diabetic retinopathy telescreening, Diabetic Medicine 22 (6) (2005) 794–802.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), SIGN 55: management of diabetes. (2001) SIGN, Edinburgh .

Z Simmons, EL Feldman, Update on diabetic neuropathy, Neurology 15 (5) (2002) 595–603.

BG Stuckey, MN Jadzinsky, LJ Murphy, et al., Sildenafil citrate for treatment of erectile dysfunction in men with type 1 diabetes: results of a randomized controlled trial, Diabetes Care 26 (2) (2003) 279–284.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group, Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33), Lancet 352 (1998) 837–853.

L Vileikyte, H Leventhal, JS Gonzalez, et al., Diabetic peripheral neuropathy and depressive symptoms: the association revisited, Diabetes Care 28 (10) (2005) 2378–2383.

G Williams, JC Pickup, Handbook of diabetes. 2nd edn. (1998) Blackwell Science, Oxford .

G Williams, JC Pickup, Handbook of diabetes. 3rd edn. (2004) Blackwell Science, Oxford .

AY Wu, NC Kong, FA de Leon, et al., An alarmingly high prevalence of diabetic nephropathy in Asian type 2 diabetic patients: the MicroAlbuminuria Prevalence (MAP) Study, Diabetologia 48 (1) (2005) 17–26.