CHAPTER 9 Back Pain: Neck, Upper Back, and Lower Back

INTRODUCTION

Statistics show that about 150 million Americans suffer from acute or chronic lower back pain and spend an estimated $20 billion to $50 billion a year in treating their problems.2 At any given time more than 2.6 million adults are disabled by chronic lower back pain. Reliable statistics as to how many Americans suffer from neck pain are not currently available, although one survey found that two thirds of the people surveyed had had significant neck pain at some time in their lives and 22% have neck pain that is bothersome.3

An interesting and disturbing study that appeared in 1994 in the New England Journal of Medicine found no direct correlation between structural abnormalities revealed on MRI and back pain: among 98 people without back pain, two thirds had spinal abnormalities, including herniated, bulging, or protruding intervertebral disks, disks with minor “degenerative joint changes,” and flattened narrowed disks, especially at the L5-S1 level.4 An investigation based solely on anatomic structure fails to produce an accurate diagnosis in 80% to 90% of patients with lower back disorders (LBD).5

BRIEF REVIEW OF THE NEUROMUSCULAR STRUCTURE AND SOFT TISSUES OF THE SPINE

This chapter presents a brief discussion of the neuromuscular system of the spine in order to assist acupuncture practitioners in understanding the possible underlying causes of back pain and to enable them to draw conclusions about the possibility of repairing the trauma. This information will help the practitioner to judge the likely therapeutic efficacy of acupuncture treatment for a given patient: whether acupuncture alone will be sufficient to achieve the desired result, whether the use of acupuncture by itself will be insufficient and other modalities should be involved, and whether the patient should be referred to other medical experts for further evaluation by means of X-rays, MRI, and so forth.

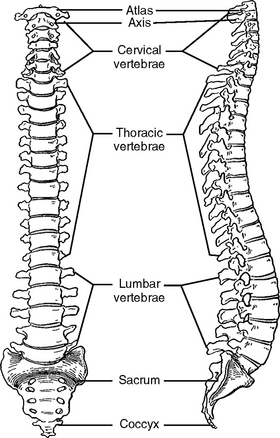

The entire spine (vertebral column) is made up of 34 bony vertebrae (Figure 9-1) and six additional elements: nerves, muscles, tendons, ligaments, disks, and various connective tissues. The erect spine consists of four physiologic curves: the cervical and lumbar lordosis (concave to the back) and the thoracic and sacral kyphosis (convex to the back). All of the four curves conform to the center of gravity.

Figure 9-1 The vertebral column as a whole, anterior and lateral views.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.)

Numerous types of neck and lower back pain are triggered by mechanical abnormalities or injuries, inflamed soft tissues, or degenerative diseases, and of course, the pain can be idiopathic, or “origin unknown.” Please note that the INMAS protocol (see Chapter 5) can be used successfully for pain management regardless of which underlying causes produce the pain symptoms as long as the symptoms are physiologically recoverable.

The Foundation of the Spine: The Coccyx and the Sacrum

An analogy between the spine and a big tree will help to illustrate why many patients experience pain in this area. The trunk of a big tree (like the spine) has to support the canopy (the head) and numerous heavy branches (the upper limbs, ribs, and internal organs) that sprout from the trunk. This construction subjects the trunk to continuous mechanical stress and eventually the stress will affect the root system (the coccyx and sacrum bones).

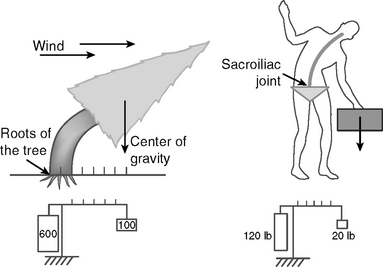

The root system must be very strong and practically immovable to give adequate stability to the trunk and heavy branches of the tree. In calm weather, the tree ensures its symmetrical balance by having its branches spread in all directions and by evenly distributing gravitational stress among all the roots, which also spread in all directions. When a strong wind tilts the tree to one side, the symmetrical balance is lost and the roots from the opposite side of the tree sustain huge stress, which is many times higher than the weight of the tree (Figure 9-2). Using the physical principle of leverage, we can calculate the stress applied to the root system on the affected side of the tree. For example, if a tree weighs 500 pounds at its center of gravity, the affected part of the root system will sustain a stress of more than 5000 pounds.

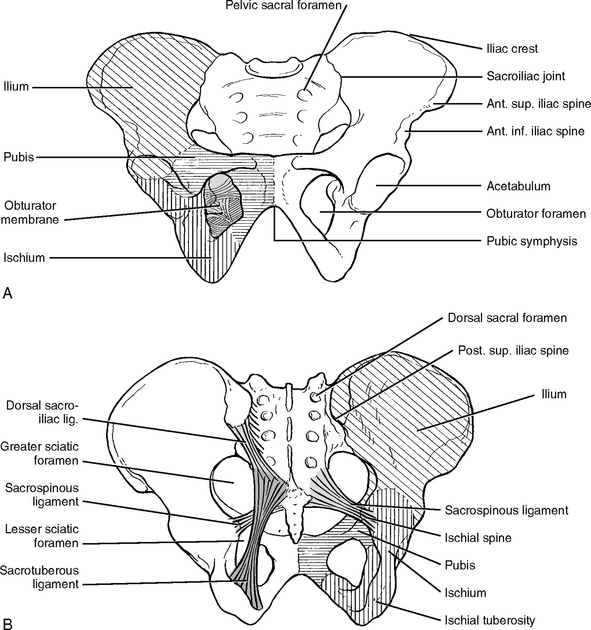

The sacroiliac (SI) joints differ from other joints. They are thicker and stronger and can move only a few millimeters (Figure 9-3). This relative immobility of SI joints stabilizes the spine against gravitational forces. The SI joints are also subject to the tremendous stresses and strains created by the forces of asymmetric imbalance as discussed in the above examples. The SI joints have to support the trunk, shoulders, arms, and head and to ensure a full range of motion.

INMAS is effective in treating painful symptoms related to the SI joint region. Most SI joint pain is caused by inflammation of the soft tissues such as nerves and ligaments. When needles are inserted into inflamed tissues, the needle-induced lesions break the blood vessels, thus stimulating the local defense immune reaction. As a result of the immune reaction, inflammation of the soft tissues of the SI joint is reduced. The needle-induced secretion of endorphins from the spinal cord and the brain reduces the physiological stress caused by the joint pain, thereby accelerating tissue healing. Eventually, this process restores normal SI joint function. The degree of recovery of SI joint function depends on the degree of the injury and the self-healing capability of the body.

The INMAS protocol for treating SI joints is provided at the end of this chapter.

Lumbar Spine (L1-L5)

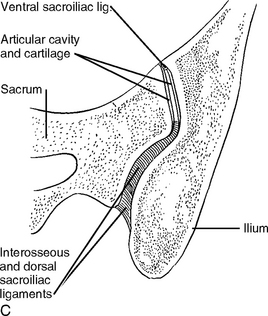

The lumbar part of the spine is situated above the sacrum. The lumbar spine has five large vertebrae, and each vertebra has two upper facets (superior articular facets) that emerge from the top and two lower facets (inferior articular facets) that descend from the bottom (Figure 9-4).

Thoracic Spine (T1-T12)

The two lower ribs are short and are called floating ribs. They do not enclose anything, but they allow a broader range of motion than the first 10 thoracic vertebrae. The joints between the last thoracic vertebra and the first lumbar vertebra (between T12 and L1) also facilitate side-to-side rotation of these relatively immobile regions. This rotation implies a significant amount of wear and tear on these lowest two thoracic vertebrae and may result in various pain syndromes and degenerative diseases like osteoarthritis.

Cervical Spine

The cervical spine has seven vertebrae. These vertebrae get progressively smaller as they approach the bottom of the skull (see Figure 9-4). The cervical spine is the upper part of the spine and is capable of a great range of motion, in contrast to the foundation of the spine, the sacrum and coccyx, which has fused bones and almost immovable sacroiliac joints. For instance, the cervical spine allows the neck to turn 90 degrees in either direction, the ear to almost touch the shoulder, and the head to lean backwards more than 70 degrees.

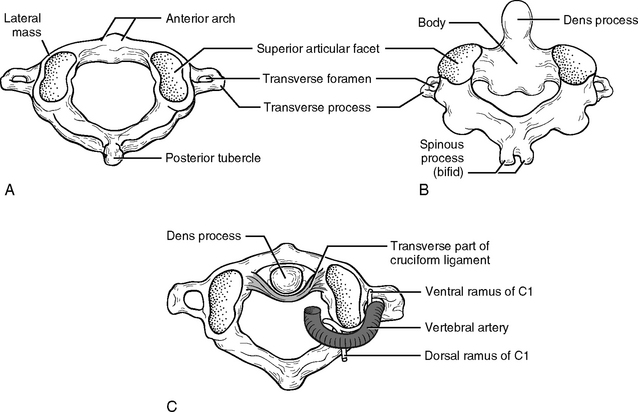

The cervical spine is composed of two major complexes: the upper cervical segment (C1 and C2) and the lower cervical segment (C3 to C7). The occipital bone of the skull sits on the ring-shaped bone C1, which is called the atlas. The joint between them (0-C1), which is the first joint of the cervical spine, is called the atlantooccipital (AO) joint. This joint provides a very important function by anchoring the skull to the spine, and it is therefore necessarily the most immobile joint of the neck spine.

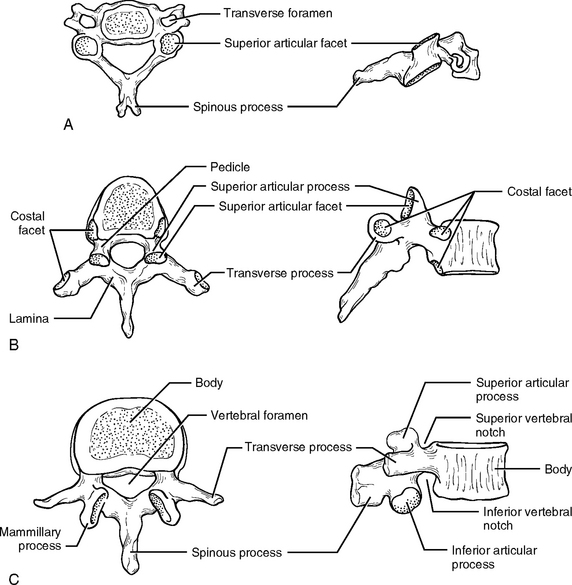

The distinctive feature of C2 is a blunt toothlike process called the odontoid process, or dens, projecting superiorly from the body (Figure 9-5). C1 uses the dens of C2 as its pivot for rotation. The front inner surface of the ring-shaped C1 is attached to the dens of C2, allowing C1 with the skull on top of it to rotate against the dens.

Figure 9-5 Posterosuperior views of the atlas (A) and axis (B). C, Superior view of the atlantoaxial joint.

(From Jenkins D: Hollinshead’s functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.)

The peripheral nerve network in the neck region is some of the most complicated nervous wiring in the body. Eight cervical nerves emerge from the intervertebral foramen to form the cervical plexus from C1 to C4, and brachial plexus from C5 to T1. The intervertebral foramen is the passage from which the spinal nerve emerges. The neck is also the passage for the autonomic nervous system, which balances the physiological activities of the majority of the internal organs. Thus, pathological neck problems will affect not only the head and the arms but many different organs ranging from the brain to the large intestine.

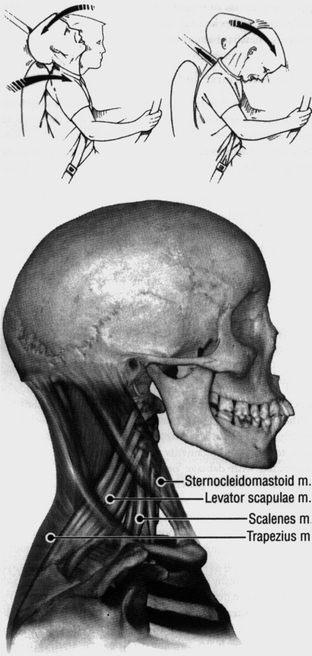

During a whiplash accident, the horizontal force from the back causes the neck to overextend and overflex (Figure 9-6), which causes damage to both posterior and anterior joints. In addition, the translational back-and-forward movement of the upper vertebra closes the vertebral canal, which causes injury to the spinal cord. Understanding the basic mechanical structure of the spine and the nature of pathological damage sustained by the spine during an accident is the key to effective acupuncture treatment for back pain.

Figure 9-6 Overextension and overflexion during a “whiplash” injury.

(From Wall P, Melzack R: Textbook of pain, ed 4, Edinburgh, 1999, Churchill Livingstone.)

The INMAS protocol for treating whiplash will be provided in the end of this chapter. Please note that in the case of whiplash, pain symptoms such as neck pain, lower back pain, and upper back pain are all closely related because functionally and anatomically all three parts of the spine—the neck, the upper back, and the lower back—are interrelated structures that should be understood as one whole entity and treated as such.

MUSCLE

Muscles perform at least three major mechanical functions:

Weak back muscles are not able to adequately perform the following functions:

Usually a spasm has no serious consequence and the pathological effect is not longlasting. However, when a tear caused by strain or spasm is severe or repeated, scar tissue is formed, which weakens the muscles and irritates the nerves, thus provoking pain syndromes. Acupuncture needling is very effective in the treatment of strained tissues and muscle spasms, especially at the acute phase.

Weak abdominal muscles often result in back pain. The abdominal muscles do much of the work when lifting or carrying loads, and so when weak abdominal muscles try to relieve the strain on back muscles during such activities, they will sustain further damage. This is why the abdominal muscles should be examined and needled in clinical acupuncture practice when a patient presents with back pain.

The Shortened Muscle Syndrome

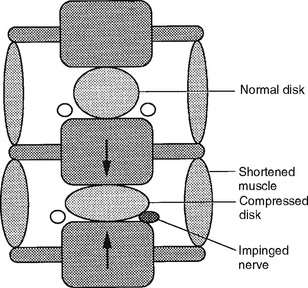

The paraspinal muscles, when shortened, draw two adjacent vertebrae closer together, which narrows the intervertebral space and foramen (Figure 9-7). The results are a bulging disk and a compressed nerve root. A vicious circle is gradually built up: shortened muscles cause compressed nerve roots (radiculopathy), and compressed nerve roots lead to further muscle shortening.4

Figure 9-7 Shortened paraspinal muscles across an intervertebral space compress the disk and nerve root.

(From Filshie J, White A: Medical acupuncture: a Western scientific approach, Edinburgh, 1998, Churchill Livingstone.)

Acupuncture treatments can break this vicious circle by using needles to produce a minimal tissue injury, which stimulates the relaxation of muscle stress. The primary goal in the treatment of muscle shortening is relaxation of the affected muscle, and acupuncture needling achieves this goal more swiftly and precisely than any other medical modality. When a fine acupuncture needle pierces a muscle, it pushes aside tissue, disrupts the cell membrane, and inflicts a minute tissue injury, which mechanically creates a brief outburst of microcurrents (injury potentials). The microinjury that results from needling generates relatively longlasting currents that stimulate the mechanism of repair and regeneration of the affected tissue (see Chapter 3). Thus, acupuncture treatment eliminates the pathological condition responsible for muscle shortening. After treatment a patient feels either no pain or a significant alleviation of pain.

NERVE TISSUE

Injury to nerves leads either to an involuntary, intense contraction (spasm) of the muscles in the body, the blood vessels, and organs, or to weakness or paralysis of the muscles as a result of insufficient contraction. A spasm causes overstimulation of sensory nerves and undernourishment of muscles because the tightness constricts blood vessels and interrupts the mechanism of nourishment. Weak muscles can easily be overstretched and thus be susceptible to painful tissue damage because this pathological overstretching releases chemicals that irritate the muscles (Chapter 3). Some of the pathophysiologic conditions of the spinal cord are discussed below.

Spinal Stenosis

Lumbar spinal stenosis is defined as a condition involving any type of narrowing of the spinal canal, nerve root canal, or tunnels of intervertebral foramina.5 Spinal stenosis can be either congenital or acquired. Acquired stenosis may be due to degenerative conditions (spondylolisthesis, see below), failed medical procedures (postlaminectomy, postfusion, postchemonucleolysis), or posttraumatic injuries, or it may be secondary to disk herniation (see below). Narrowing can occur in one or several locations of the same vertebral segment or it can affect several segments. The canal space can be narrowed by pathological changes in the soft tissues, scar tissue, or bony tissue impingement (bone spurs). Severe stenosis results in nerve compression. Soft tissue encroachment or abnormal bone growth such as osteophyte formation reduces the size of the intervertebral foramen and causes foraminal stenosis.

Some patients with spinal stenosis experience numbness or a burning sensation in both legs. Narrowing of the spinal canal or nerve root canal causes the painful condition known as a pinched nerve, which also irritates muscles and causes muscle pain. Acupuncture needling can relax the groups of erector spinae muscles from the neck to the sacral regions, thus reducing tension and increasing blood circulation between vertebral joints, which alleviates the pressure on the nerve roots and may help reduce swelling or inflammation of soft tissues in the affected region. Based on this mechanism, acupuncture therapy is helpful in mild cases of spinal stenosis especially when applied in combination with proper physical exercise. For example, one of our patients developed both spinal and foramenal stenosis at age 74 after four lumbar surgeries. Acupuncture therapy was able to reduce the pain to a very tolerable level and this patient now resumes normal life, including home office work and some gardening. Acupuncture therapy is not effective for severe cases of stenosis. When the cause of pain is not physiologically repairable such as in severe stenosis, acupuncture provides limited or no relief.

Radiculopathy

Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis is the forward displacement of a vertebra over a lower vertebra. Usually this out-of-alignment condition happens at the fifth lumbar vertebra over the sacrum, or the fourth lumbar over the fifth. The forward slippage of the vertebra can lead to spinal stenosis and radiculopathy, which result in muscles that are tight and painful in response to movement, especially movement in the back and buttocks area.

Sciatica

When patients have sciatica of unknown etiology, and do not experience significant relief after sufficient acupuncture sessions (Chapter 6), they should be referred for further medical evaluation.

Piriformis Syndrome

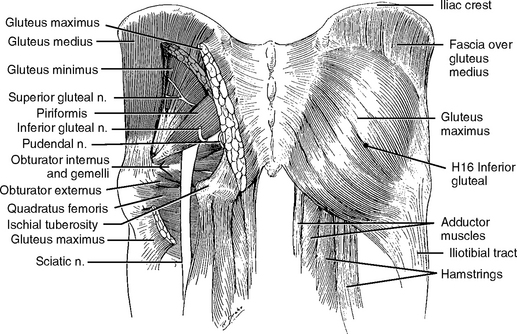

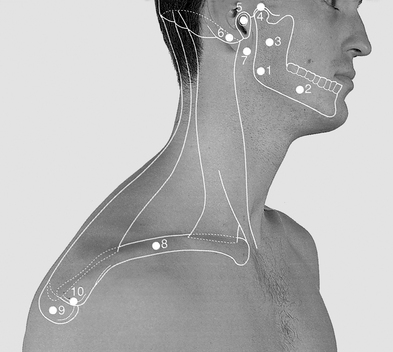

Current medical opinion holds that lower back pain with sciatic radiation may be caused by a compression of the sciatic nerve by the piriformis muscle as the nerve emerges from under the muscle in the buttock (Figure 9-8). The piriformis syndrome is characterized by pain along the sciatic nerve. The pain is usually more severe in the sitting position than in the standing position, and it is often more troublesome early in the morning if patients sleep on their backs. Tenderness in the buttock area, especially at the center of the gluteus maximus muscle, can be palpated. This tenderness is located at acupoint H16 inferior gluteal in our INMAS. This acupoint is sensitive in most healthy people but this does not mean they all have piriformis syndrome.

Some in the medical profession believe that the piriformis syndrome cannot trigger such a significant amount of pain because the piriformis muscle is too small to have such a powerful impact on the sciatic nerve. Regardless of whether this opinion is justified, patients with piriformis syndrome can be benefited by acupuncture needling. The practitioner can easily find the tender acupoint H16 inferior gluteal and needle it deeply with a long needle all the way to the piriformis muscle. This needling of the piriformis muscle itself reduces tension and inflammation. If there are other tender points around H16, they should be located by palpation and needled for complete pain relief.

INTERVERTEBRAL DISKS (HERNIATED DISK)

In addition to gravitational pressure, the disks are affected by muscular contraction. Approximately 3% to 10% of disk fluid is lost during 10 hours of daily activity but is recovered after at least 2 hours of rest.6 Tight or stiff back muscles reduce the flexibility of the spine and impede water recovery of the disks.

Both herniated and displaced disks are often caused by chronically poor posture, weak muscles in the back, damage to ligaments, degeneration of vertebral components, acute injuries, and pregnancy. Disk degeneration starts to appear after midlife because of the continuous process of water loss in the spinal disks. Most cases of herniated disks in people between the age of 35 and 50 are attributed to performing tasks that are too physically challenging. After the age of 50, most people will have some degeneration in about 90% of their disks.

Herniated Disk (Herniated Nucleus Pulposus)

A herniated disk may cause pain because of anatomic abnormality and chemical irritation.

In addition to mechanical encroachment, the injured disk releases nociceptive chemicals of the matrix, leading to inflammation of the dural sheath, ligament, and nerve roots. Inflammatory cells such as macrophages, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts are found in surgically removed disk material. Recent research shows that cytokines and chemokines also play a role as pain triggers.7

In cases of a mild herniated disk, acupuncture needling relaxes the tight back muscles, thereby reducing the pressure applied to the joint by these muscles. The relaxed muscles are enabled to obtain sufficient blood circulation, which causes an increase in nutrition, oxygen supply, and removal of toxins, allowing the self-healing potential to bring under control the biochemical irritation to the nerves. According to some researchers, the body tissues are even able to absorb the herniated materials.8

Self healing of a herniated disk is a very important concept as described by the well-known neurosurgeon Dr. Frank T. Vertosick, Fellow of the American College of Surgeons10:

When our body can absorb the herniated disk in mild cases, acupuncture will accelerate this process.

Several patients with severe lower back pain and MRI-confirmed herniated disks came to our clinic for pain relief before making a decision about whether or not to have surgery. After treatment in our practice some of these patients experienced a reduction in or total relief of pain and decided to delay surgery indefinitely.

TENDONS AND LIGAMENTS (TENDINITIS)

Tendinitis

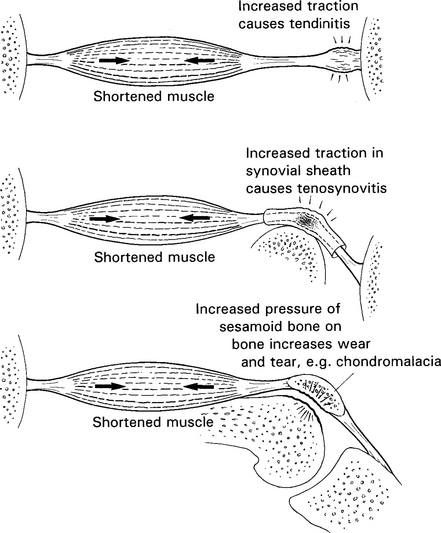

Overstretched tendons, whether strained or sprained, will be inflamed. Many professional and amateur athletes have experienced tendinitis, such as pain in the region where the hamstring originates on the ischial tuberosity, or the insertion area on the medial side of the knee, or the upper part of the medial surface of the tibia. In upper limbs, lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow) and medial epicondylitis (golfer’s elbow) are very common tendon injuries. These types of tendinitis are caused by repeated and excessive extension-flexion motions and, in the upper limbs, by rapid pronation-supination. These repeated motions first make muscles tight and fatigued so they cannot relax fast enough or to a sufficient extent. Then the tight muscles start to exert force on the tendons, which results in tendinitis. Upon examination of the affected muscles, tender points are found in the affected tendons and muscles as well. In most repetitive injuries, tendinitis is clearly caused by tight, shortened, and fatigued muscles (Figure 9-9).

JOINTS

Facet Syndrome

Facet joints of the spine, like all joints in the body, are mechanically aligned to sustain and secure movement. For example, due to the mechanical design necessary to meet the functional demands of the body, the cervical spine is more mobile but less stable while the lumbar spine is less mobile and more stable. Therefore the facet joints of the cervical spine are designed to allow flexion (bending forward), extension (bending backward), and rotation to the side while the lumbar facet joints resist rotation.

In young people, strong or abrupt movement can cause the lumbar facet joints to slip out of normal alignment. When this happens, the facet joints become locked and extremely painful. With aging many minor traumas are accumulated at the joint surface. The accumulated effect of these injuries gradually produces permanent swellings and deformities on the joint surfaces, which are no longer smooth. When such joints are forced to move or to support weight, the deformities bear the full impact of pressure that is normally evenly distributed over the entire joint surface. This pathological condition chemically and mechanically provokes the nerves to create pain.

Sacroiliac Joint Derangement

There is a difference of opinion in the medical profession as to whether SI joint injuries are a common cause of back pain. Some believe that SI joint injuries account for many cases of lower back pain because the mechanical stress of the spine converges on the SI joints. When a person flexes forward asymmetrically or rotates the body, most of the stress of supporting the motion is borne by one of the two SI joints. In a study on two hundred patients with “workmen’s compensation” type of injuries of the lower back, it was found that more than 80% of the patients could localize their pain to one or both SI joints while injuries involving the spinal ligaments, muscles, iliolumbar ligaments, facet joints, ribs, or protruding disks were less common.4

Others believe that SI joint injuries are rarely the source of lower back pain except in unusual types of arthritis or pelvic dislocation,11 and the reasons usually given are that SI joints form a very stable intersection, that SI joints are very well fused in adults, and that the ligaments on either side of the SI joints are among the strongest in the body. It is interesting to note that SI joint derangement does not show up on X-rays, MRIs, or electromyography (EMG).

The theoretical disagreement on SI joint etiology does not affect the good results achieved by acupuncture therapy in most patients diagnosed with SI joint problems. In the case of lower back pain, an acupuncture practitioner should carefully examine and palpate the lumbar, sacral, and iliac crest areas including the surface just on the top of the SI joints. Usually, if the SI joint area is sensitive, the iliac crest area, buttock muscles, and iliotibial band area are also sensitive and tight. In this case the acupoints H14, H15, H16, and H18 are very sensitive or even painful upon palpation because all the peripheral nerves are irritated or inflamed because of the injured SI joints. Desensitizing these nerve points reduces pain, relaxes the affected muscles, and improves regional blood supply, thus helping the recovery of the soft tissues of the SI joints.

NEUROPATHY, AMYOTROPIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS, MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

These three neurological diseases can be the cause of severe back pain.

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurological disease in which sclerotic patches form in the myelin sheath of the nerves in the central nervous system (the spine and brain). The course of the disease is usually prolonged, with remissions and relapses over many years. The prevailing medical opinion is that an inherited immune response is probably responsible for the production of autoantibodies that attack the myelin sheath of the central nervous system. Patients with MS often show symptoms in two or three limbs; for example, tingling in one leg and numbness in one arm, trouble controlling bowel and bladder, dimming vision in one eye, and weakness in one leg. Acupuncture is helpful in providing temporary pain relief by relaxing muscles, improving blood circulation, and desensitizing the peripheral nerves but does not have long-term therapeutic results due to the irreversible process of the disease.

UPPER BACK (THORACIC) PAIN

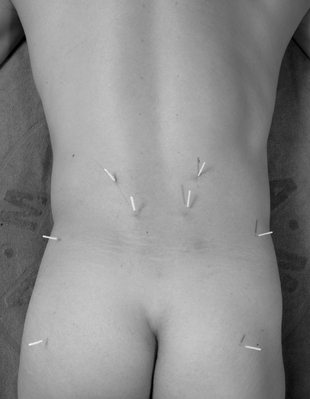

Acupuncture is routinely effective in relaxing the tender acupoints and de-stressing the muscles. However, practitioners should be very cautious while working in this region because deep needling can cause pneumothorax. Needles always should be tilted toward the spinal cord and should not exceed 1 inch in length. To effectively and safely needle a particular tender acupoint, if the lung is below the acupoint, a practitioner can grasp and lift up the muscle while inserting the needle (Figure 9-10). The INMAS protocol for treatment of upper back pain will be provided at the end of this chapter.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN TREATING NECK PAIN

The neck serves two basic functions: (1) as a passage for blood, nerves, food, and air; and (2) as a pedestal to support the head. The neck connects the head, trunk, and upper limbs. Many important structures are crowded in these areas. Physiological problems with the neck, including the neck pain itself, have a systemic impact on the physiology of the whole body, causing problems in the respiratory system, the cardiovascular system, the endocrine system, and the digestive system, as well as affecting activities of the autonomic and lymphatic systems. Clinical evidence shows that treating neck pain will help to improve many other pathologic conditions of the body.

It is important to note that proper neck exercises following the treatments will help to strengthen the neck muscles and joint structures and to prevent a recurrence of pain.

Patterns of Neck Pain

A detailed evaluation is required in cases where pain has persisted for more than 3 or 4 months.

Whiplash

The leading source of trauma in developed countries is automotive accidents. Most of these create some degree of whiplash, so it is not surprising that whiplash has become a common cause of neck and lower back pain. The mechanics of whiplash are clearly understood but the extent and type of injuries vary greatly. All whiplash victims should seek early treatment regardless of whether or not they experience pain immediately following the accident because, as discussed above, a whiplash injury that is not painful after the accident may cause pain as much as 5 to 10 years later. If early treatment is provided, acupuncture can effectively reduce most whiplash pain, and it will also activate the recovery of most soft tissue injuries, as well as improving other related symptoms such as arm or lower back pain or numbness, dizziness, and nausea. The efficacy of acupuncture decreases proportionally as the treatment is delayed because in time the tissue damage invades deeper tissues and structures.

Pain caused by whiplash-related injuries may radiate to the shoulders, arms, and the area between the shoulder blades. Pain in the shoulder, between the shoulder blades, or in the arms can be referred from the neck nerves or facet joints. Numbness, tingling, or heaviness in the arm and/or hand, especially in the ring and little fingers, are common symptoms. Lower back pain is also among the common complaints.

NECK AND LOWER BACK PAIN CAUSED BY SPORTS AND RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES

Bicycling

Bicyclists may suffer neck and lower back pain; wrist pain; hamstring muscle pain from road vibrations; strain and fatigue of the muscles in the back of the neck, shoulders, and between the shoulder blades; and strain and fatigue of the lumbar muscles and leg muscles. They also may suffer from the consequences of poor body and/or head position, such as excessive extension or flexion of the neck and flattening of the lower back lordosis. All of the above may also result if the bicycle is not properly adjusted to the height of the user.

NEEDLING SAFETY IN TREATING NECK AND LOWER BACK PAIN

The Neck

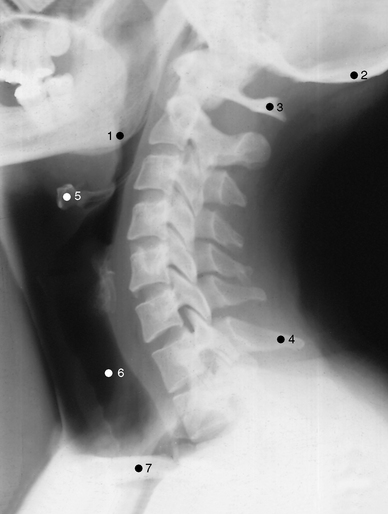

However, the tip of the transverse process of C1 (atlas) can be felt 1 cm anteroinferior to the tip of the mastoid process (Figure 9-11). A practitioner should first find this point and then ask the patient to rotate the head slowly from side to side, which movement allows the practitioner to feel the transverse process of C1. If a neck injury patient feels a tender sensation during palpation of this region, the transverse process of C1 should be needled all the way to touch the bone.

C2 has a longer spinous process than C3, C4, and C5 and can be palpated with little pressure. The spinous processes of C3-C5 are short, lie deep to the surface, and are difficult to feel. The spinous process of C7 is more prominent than that of C6 (Figure 9-12) but both spinous processes are easily palpable when a patient’s neck is flexed as far as possible.

The posterior part of the neck is responsible mostly for extension and side rotation. The back muscles must be sufficiently strong to perform such motions. The back muscles (extensors) sustain more stress than the front muscles when the cervical curve is not properly maintained, such as when working on computers, or overextended, as when looking upward. As the stress accumulates, the back muscles are subject to tightness, spasm, inflammation, strain, or sprain, and these may lead to reduced blood circulation and hypoxia in the muscles.

The Back

The importance of understanding the anatomy of the back cannot be overemphasized. All acupuncture practitioners should have a solid working knowledge of the anatomy of the back. The back is the most important part of the body in acupuncture medicine. The spinal cord sends its peripheral nerves to all organs through structures related to the back. Sensory nerve roots and autonomic ganglions are located close to the back. Acupoints in the back are used to treat almost all the symptoms that are treated by acupuncture.

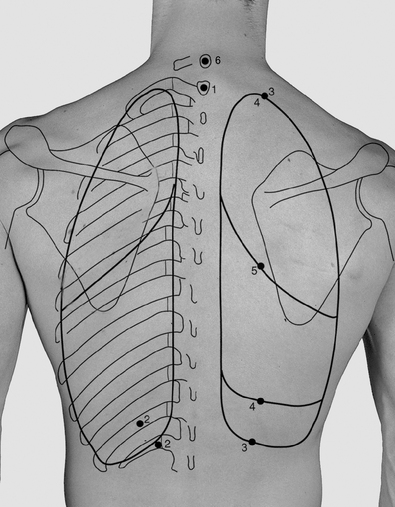

Avoiding Puncturing the Lungs (Pneumothorax)

Figure 9-13 shows the outline of the pleura and lungs, as viewed from the back during gentle respiration. Viewed from the back, the apices of the lung are close to the transverse processes of T1. However, if observed from the front, the apices of the lung project superiorly through the thoracic inlet into the neck posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Practitioners should be very careful when working in the area just above the medial part of the clavicle bone and should use fine needles of 1.5 cm in length. Deep needling also should be avoided when needling acupoint H3 spinal accessory on the top of the shoulder because the apices of the lung are close to the base of the neck; a needle of 2.5 cm in length suffices in most cases. When deeper needling is needed such as when a nodule is detected in deep tissue, a practitioner can grasp and lift the trapezius muscle so as not to puncture the apex of the lung below (see Figure 9-10).

Three parameters are critical when using paravertebral acupoints (PAs) in the thoracic area (T1-T12) shown in Figure 9-13: (1) the direction of the needle; (2) a safe distance from the needling point to the midline of the spine; and (3) the depth of needling.

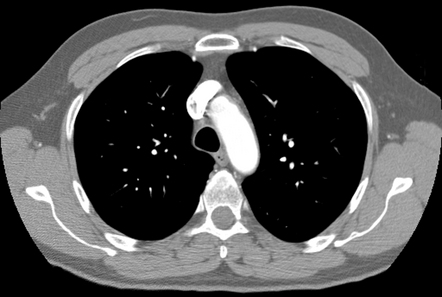

Figure 9-14 shows the transverse section of the lung at the T3 level. To avoid puncturing the pleural cavity, it is safer to tilt the tip of needle toward the body of the vertebra (toward the midline). T3 and the base of the spine of the scapula (medial angle) are at the same level. The safe distance at the T3 level can be determined by first palpating the medial angle of the scapula and then locating the tip of the spinal process of T3. The medial one third of the distance between the medial angle and the spinal process of T3 is the safe distance for needling. Needling at a distance farther from the midline runs the risk of puncturing the pleural cavity. The depth of needling depends on the physical size of a patient’s body. For the sake of safety, it is best to needle at a depth of 2.5 to 3.0 cm for an average-sized person. If a patient is suffering from neuralgia or herpes simplex/zoster, fine needles of 1.5 cm in length should be used.

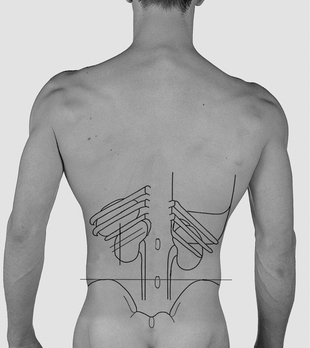

Avoiding Puncturing the Kidneys

The kidneys are two bean-shaped organs lying on each side of the vertebral column. The position of the kidneys varies somewhat with posture, body build, and respiration. Each kidney may move vertically about 3 cm when the diaphragm moves during deep breathing. In the prone position, the superior poles of the kidneys are protected by the 11th and 12th ribs (Figure 9-15), while the inferior poles extend to the level of L3 for the right kidney and a little lower than that for the left kidney due to bulky liver lobes. With respect to the midline, the superior poles are in the epigastrium, each 2.5 cm from the midline, while the inferior poles are 7.5 cm from the midline, slightly above the supracristal plane. The right kidney is about a fingerbreadth superior to the crest of the ilium. Based on the above anatomic description and on our clinical experience, the safe needling distance at the L1 level is about 2.5 cm (about 1 inch) from the midline.

Figure 9-15 Surface anatomical positions of the kidneys.

(Modified from Lumley J: Surface anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical examination, ed 3, Edinburgh, 2002, Churchill Livingstone.)

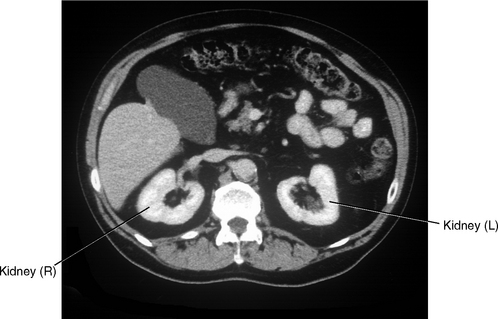

The important acupoint H15 is located on the lateral border of the erector spinae at the L2 level. The cross section at this level (Figure 9-16) shows that the distance between the body surface and the posterior surfaces of the kidneys is about one fifth to one sixth of the posterior-anterior body axis at the L2-umbilicus level. It is possible that the usual prone position for needling the low back may shorten this posterior-anterior body axis.

Figure 9-16 Transverse CT image at the level of L2 shows the topography of the kidneys.

(From Gosling J, Harris P, Whitmore I, Willan P: Human anatomy: color atlas and text, ed 4, Edinburgh, 2002, Mosby.)

Based on the above information about the topography of the kidneys, it is best to use needles of 4 cm in length for acupoints at L1 levels and to use needles of 5 cm in length for acupoints from the L2 to L5 levels. If the selected acupoints are situated on the ridge of the erector spinae muscles, the needle should be positioned perpendicular to the muscle surface. If the selected acupoints are located on the lateral border of the erector spinae muscle, the needle is tilted toward the midline.

TREATMENT PROTOCOL OF BACK PAIN (FOR BOTH THE NECK AND LOWER BACK)

Please note that PAs become SAs when treating neck and back problems.

Neck Pain and Upper Back Pain

Palpate the following HAs to locate the directly injured area, which will be unique to each patient:

| Neck: | H2 great auricular, H7 greater occipital |

| Shoulder: | H3 spinal accessory, H13 dorsal scapular |

| H8 suprascapular | |

| Upper back: | H20 spinous process of T7, H21 posterior cutaneous of T6 |

| Lower back: | H14 superior cluneal, H15 posterior cutaneous of L2 |

| H16 inferior gluteal, H22 posterior cutaneous of L5 | |

| H18 iliotibial |

Lower Back Pain

| Neck: | H7, |

| Shoulder: | H3, H13, H8 |

| Upper back: | H20, H21 |

| Low back: | H15, H22, H14, H16 |

| Low limb: | H18, H11, H10 |

REFERRED CAUSES OF BACK PAIN

| Gastrointestinal origin: | Perforated internal organs |

| Biliary origin: | Obstructed bile duct, distended gallbladder |

| Pancreatic origin: | Pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma |

| Renal origin: | Kidney stones, urethral stones, pyelonephritis, renal carcinoma, bladder carcinoma |

| Vascular origin: | Abdominal aortic aneurysm, arterial occlusive diseases |

Acupuncture can help patients who suffer lower back pain that is referred from a diseased organ, if it is used as a supplementary therapy.

1 Loeser JD, editor. Bonica’s management of pain. ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2001:1475.

2 Fishman L, Ardman C. Back pain: how to relieve low back pain and sciatica. New York: WW Norton, 1999;13.

3 Schofferman J. What to do for a pain in the neck. New York: Fireside, 2001;15.

4 Ivker RS. Backache survival: the holistic medical treatment program for low back pain. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 2003;25.

5 Spratt KF, Lehmann TR, Weinstein JW, et al. A new approach to low-back examination: behavioral assessment of mechanical signs. Spine. 1990;15:96-102.

6 Gunn CC. Treating myofascial pain: intramuscular stimulation (IMS) for myofascial syndromes of neuropathic origin. HSCER, Seattle: University of Washington, 1989.

7 Arnoldi CC, Brodsky AE, Cauchoix J, et al. Lumbar spinal stenosis and nerve root entrapment syndromes: definition and classification. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:4-5.

8 Eklund JA, Corlett EN. Shrinkage as a measure of the effect of load on the spine. Spine. 1984;9:189.

9 Ahn H, Cho Y-W, Ahn M-W, et al. mRNA expression of cytokines and chemokines in herniated lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine. 2002;27(9):911-917.

10 Vertosick FTJr. Why we hurt? The natural history of pain. San Diego: Harcourt, 2000;95.

11 Fishman S, Berger L. The war on pain. New York: Quill, 2001;139.

12 Rosse C, Gaddum-Rosse P. Hollinshead’s textbook of anatomy, ed 5, Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:611.