CHAPTER 84

Bunion and Bunionette

David Wexler, MD, FRCS (Tr & Orth); Dawn M. Grosser, MD; Todd A. Kile, MD

Bunion

Definition

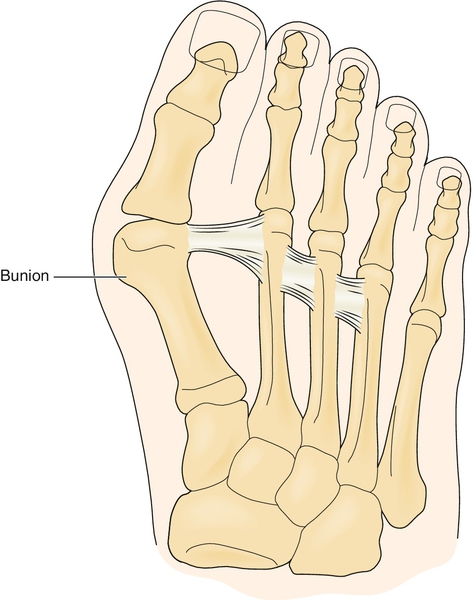

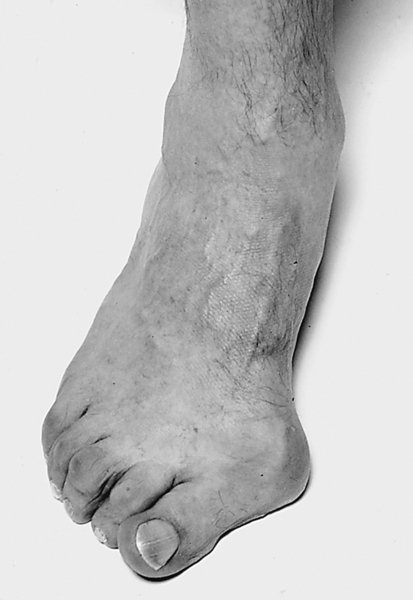

The term bunion stems from the Latin word bunio, which means “turnip,” an image suggestive of an apparent growth or enlargement around the joint. The medical term for this is hallux valgus. There is no similar Latin term for the fifth toe, so a similar process involving the fifth metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint is called a bunionette. Hallux valgus is a common deformity of the forefoot and the most common deformity of the first MTP, often causing pain (Figs. 84.1 and 84.2). The pathophysiologic process stems from both the proximal phalanx and the metatarsal bone. The proximal phalanx deviates laterally on the head of the first metatarsal, exacerbated by the pull of the adductor hallucis muscle. The lateral capsule becomes contracted, and the medial structures are attenuated. The metatarsal deviates medially, but the underlying sesamoids remain in their relationship to the second metatarsal, thus creating dissociation of the metatarsal-sesamoid complex. As these two processes occur together, the pull of the abductor hallucis moves more plantarward and the pull of the extensor tendon moves laterally, causing pronation and further lateral deviation of the great toe, respectively. As the metatarsal head becomes more uncovered, a prominent medial eminence, or bunion, is apparent. There is a bursa between the metatarsal head and the skin that may become inflamed and painful. Depending on the amount of axial rotation of the first metatarsal and pronation of the toe, the first ray becomes dysfunctional, leading to increased weight bearing on the more lateral metatarsal heads and “transfer metatarsalgia,” causing pain under the plantar aspect of the forefoot [1].

The etiology of hallux valgus is multifactorial and can be either intrinsic or extrinsic [2]. The intrinsic causes are essentially genetic and are related to hypermobility of the first ray (hallux metatarsal) at its articulation with the medial cuneiform. Ligamentous laxity (e.g., Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) can lead to this deformity as well as to variations in the shape of the metatarsal head (i.e., a rounder head is less stable than a flat one). Another contributing factor is metatarsus primus varus, or medial deviation of the first metatarsal, which is thought to be associated with a juvenile bunion [3]. Pes planus and first metatarsal length have also been evaluated for their contribution to hallux valgus, but findings are equivocal [4].

The principal extrinsic cause is inappropriate, nonconforming footwear, with abnormal valgus forces creating deformity [5]. This is particularly notable in women who wear high-heeled shoes with narrow toe boxes. The ratio of hallux valgus between women and men has been reported to be 15:1 [6].

Symptoms

Presenting symptoms can vary. The patient may complain only of a painless prominent medial eminence. However, more commonly, there will be pain that is worse when constrictive shoes are worn and relieved by walking barefoot or with open-toed shoes. If there is significant arthritis, patients may have pain throughout range of motion of the MTP joint while walking. The bunion may become red and inflamed as the bursa enlarges and overlying skin becomes abraded by the shoe. The patient will have difficulty finding comfortable shoes. As the hallux deviates into increased valgus, it tends to impinge on the medial aspect of the pulp of the second toe, causing pressure and soreness [7].

Physical Examination

There is generally an obvious medial enlargement overlying the metatarsal head, with occasional signs of inflammation (bursitis). The great toe will be laterally deviated, and with progression of deformity, it will be pronated (axially rotated). There may be splaying of the forefoot and callosities visible under the metatarsal heads of the lesser toes. Metatarsalgia—tenderness under the metatarsal heads—may also be seen even without a callus. Passive extension of the hallux MTP joint will reveal possible limitation of range of motion (normally approximately 70 degrees). This may indicate concomitant degenerative joint disease of the MTP joint. Mobility of the hallux at the first metatarsal–medial cuneiform joint is assessed in relation to the second ray. Hammer toes are commonly noted as a consequence of the crowding in the shoe by the great toe. Depending on the patient’s medical history (e.g., diabetes), the neuromuscular evaluation is important to assess for any vibratory loss, two-point discrimination loss, or other indications of neurologic compromise. Otherwise, the neurologic examination findings should be normal.

Functional Limitations

Limitations are principally in walking long distances and wearing shoes with a narrow toe box or high heels for prolonged periods. As hallux valgus progresses, arthritis may become a component and lead to stiffness and pain with any activity (biking, hiking, walking short distances, or even standing).

Diagnostic Studies

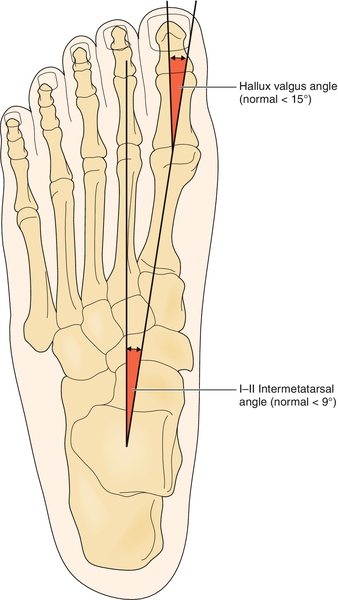

Weight-bearing plain radiographs will provide most of the necessary information. The anteroposterior view (Fig. 84.3) demonstrates the angle (Fig. 84.4) between the first and second metatarsals (intermetatarsal angle). The congruency of the first MTP joint can also be assessed for any evidence of arthritis. These all have a bearing on any proposed surgery [8,9].

Treatment

Initial

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and analgesics may be used to alleviate pain. However, key measures include education about footwear, namely, shoes with low heels, well-cushioned soles, extra depth, and broad toe boxes. Many orthoses are available and are of varying efficacy. These include sponge wedges to be placed in the first web space, more formal braces that attempt to pull the hallux into a more neutral position, and custom-molded orthotic appliances to resist foot pronation and to support the arch. A study showed promising results of a total-contact insole with a fixed toe separator that improved pain, walking ability, and the radiographic hallux valgus angle in patients with painful hallux valgus treated nonoperatively [10].

Rehabilitation

Once the structural deformity has progressed, physical therapy has a limited role. This includes mobilization of the first MTP joint and strengthening of the intrinsic muscles of the foot, which may improve symptoms, as well as focus on gait training [11]. Distraction techniques like varus stretching or toe spacers may also be useful.

Procedures

Local anesthetic and steroid injection into the first MTP joint may provide short-term pain relief but is certainly not curative and generally not recommended because steroid injections may have a deleterious effect on the soft tissue and cartilage.

Surgery

After conservative management has failed, surgery is a consideration. Over the years, a vast array of different surgical procedures have been described [3,12]. Furthermore, no single procedure has provided sufficient evidence of being superior to any other. The complication and recurrence rates can be relatively high, and satisfaction of the patient is difficult to achieve. A study reported that the desired outcome of surgery for patients is threefold: a painless great toe that “when wearing conventional shoes, gives no problems,” an improvement in the bursitis and appearance of the bunion, and the ability to walk as much as they wish [13]. These are not unreasonable goals, but it is very important to counsel patients preoperatively, explaining the complications and that there are no guarantees they will be able to return to wearing high-heeled fashionable footwear [14]. The principal goals of surgery are to relieve pain and to provide a foot capable of wearing a shoe.

The type of surgery, whether it is a distal soft tissue procedure [15] combined with a proximal metatarsal osteotomy, a distal osteotomy alone, or even an MTP arthrodesis, depends on the presenting anatomic deformity and its complexity.

Potential Disease Complications

Disease complications include ulceration of the medial eminence, metatarsalgia, callosities, hammer toe deformity, and stress fractures of the lesser toes.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Treatment can result in recurrent hallux valgus deformity, hallux varus from surgical overcorrection [16], and hallux extensus (cock-up toe). Procedures in which the first metatarsal is excessively shortened may result in transfer metatarsalgia. Osteonecrosis of the first metatarsal head can occur if the blood supply is disrupted significantly. Nonunion can occur with the osteotomies and MTP arthrodesis.

Bunionette

Definition

A bunionette is similar to a bunion as a painful bone prominence of a metatarsal head and overlying bursa, but it involves the fifth metatarsal. The fifth metatarsal deviates laterally and the fifth toe medially. It has also been called a tailor’s bunion as a cross-legged sitting position, often associated with a tailor, can cause pressure over the fifth toe and potentially encourage this deformity. Like the bunion, a bunionette has a high association with constrictive shoes and is much more common in women than in men (4:1) [4].

Symptoms

Patients may be asymptomatic or complain of irritation over the lateral eminence with tight or stiff shoe wear. Typically, when they wear open shoes without pressure over the bunionette, they have no discomfort. However, they occasionally have an inflamed bursa that is acutely painful and red. If patients adjust their shoe wear, the pain can resolve.

Physical Examination

A prominent fifth metatarsal head with a widened appearance of the forefoot is often seen. Patients may develop lateral or plantar callosities over the bone prominence. Hallux valgus may be a concomitant finding, and the foot is considered a “splay foot” if both diagnoses are present [4].

Functional Limitations

Patients typically have pain with restrictive shoe wear that is improved or absent when they are barefoot or wearing open shoes, like flip-flops, that do not put pressure over the fifth metatarsal head. Their walking tolerance may be affected when inappropriate shoes are worn.

Diagnostic Studies

Three radiographic views of the foot are obtained: anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique. Anatomic differences that can be appreciated radiographically may influence the surgical approach. These are of three types: type I, an enlarged fifth metatarsal head; type II, an abnormal lateral bowing of the fifth metatarsal shaft; and type III, a wide intermetatarsal 4-5 angle.

Treatment

Initial

Addressing the constrictive shoe wear is the first approach. Wide, extra-depth shoes or tennis shoes may help decrease the irritation and bursitis. On occasion, pronation can exacerbate the pressure of the lateral eminence against the shoe, and an orthotic can unload or change the position enough to relieve this. Patients may also take their leather shoes to a shoemaker, who can create a focal stretch over the pressure area of the shoe.

Procedures

If a callus develops, it may be débrided, or patients can be advised to use a pumice stone after daily showers to gently buff the hypertrophic tissue that accumulates laterally or plantarly. Because the discomfort from the bunionette is a pressure phenomenon, injections are not helpful. The bursitis that occasionally accompanies this deformity will improve with appropriate shoe wear and keeping the callus thin.

Surgery

More than 20 different surgical procedures have been described for the correction of a bunionette deformity. These include lateral condylectomy or distal osteotomy for type I, midshaft or distal oblique osteotomy for type II, and proximal osteotomy for type III [4].

Potential Disease Complications

Ulcerations and callosities may develop if patients continue to wear restrictive shoes.

Potential Treatment Complications

Treatment can result in recurrence of deformity, particularly with an isolated lateral condylectomy; flail toe with metatarsal head resection; malunion or nonunion of osteotomies; and vascular compromise leading to osteonecrosis, particularly with proximal osteotomies.