CHAPTER 83

Ankle Sprain

Brian J. Krabak, MD, MBA, FACSM

Definition

Ankle sprain involves stretching or tearing of the ligaments of the ankle. Ankle injuries are a common cause of morbidity in the general and athletic population, with an estimated 25,000 ankle sprains requiring medical care in the United States per day [1]. Overall, ankle sprains are slightly more likely to occur in males (50.3%) than in females (49.7%) and nine times more likely to occur in younger than in older individuals [2]. In the high-school athlete, there are an average of 5.23 ankle injuries per 10,000 athlete-exposures, most often due to traumatic ligament injuries involving boys’ basketball, girls’ basketball, and boys’ football [3]. In the collegiate athlete, ankle sprains represent 15% of all athletic injuries and account for almost 25% of injuries of men’s and women’s collegiate basketball and women’s volleyball athletes [4,5].

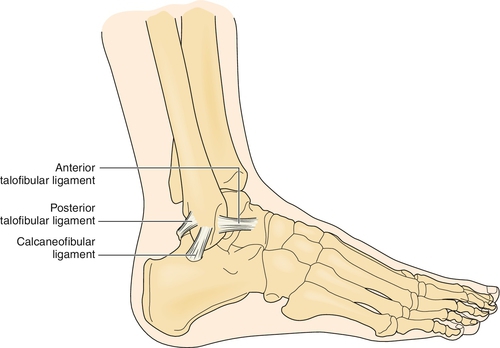

Eighty-five percent of all ankle sprains occur on the lateral aspect of the ankle, involving the anterior talofibular ligament and calcaneofibular ligament (Fig. 83.1) [6]. Another 5% to 10% are syndesmotic injuries or high ankle sprains, which involve a partial tear of the distal anterior tibiofibular ligament. Identification of syndesmotic sprains is important; they may have a prolonged recovery compared with milder lateral ankle sprains and are more likely to require surgery. Only 5% of all ankle sprains involve the medial aspect of the ankle as the strong medial deltoid ligament is resistant to tearing. Most ankle sprains will recover during several weeks to months, depending on the grade of injury. It is estimated that 20% to 40% of ankle sprains result in chronic sequelae [7]. An ankle sprain that does not heal may be caused by injuries to other structures and will necessitate further investigation for other causes.

The exact structure torn will depend on the mechanism of injury. The most common mechanism of injury involves foot supination and inversion, resulting in a tear of the lateral ankle structures (primarily the anterotalofibular ligament). An eversion stress to the foot or ankle will tear the medial structures (deltoid ligament), and ankle dorsiflexion with external rotation will lead to a syndesmotic injury [6,8].

Ligamentous injuries are categorized into three gradations:

Grade I is a partial tear without laxity and only mild edema.

Grade II is a partial tear with mild laxity and moderate pain, swelling, tenderness, and instability.

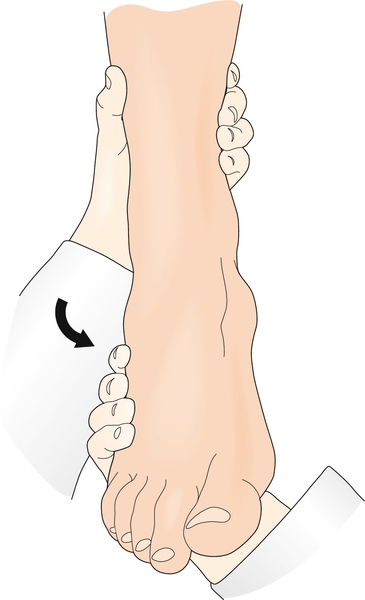

Grade III is a complete rupture resulting in considerable swelling, increased pain, significant laxity, and often an unstable joint (Fig. 83.2).

Symptoms

Acutely, the injured patient will report pain, swelling, and tenderness over the injured ligaments. Some patients report a “pop” at the time of injury. Initially, they may have difficulty with weight bearing on the injured ankle and with subsequent ambulation. They may report some ecchymosis during the first 24 to 48 hours. There may be sensory symptoms in the sural, superficial peroneal, or deep peroneal nerve’s distribution. Decreased function and range of motion along with instability are reported more often in grade II and grade III injuries.

Physical Examination

Inspection of the ankle will reveal edema and sometimes ecchymosis around the area of injury, depending on the extent of injury. Range of motion of the ankle joint may be limited by associated swelling and pain. Reduced dorsiflexion may predispose the joint to an ankle sprain [9]. Palpation should include the anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments, syndesmotic area, and medial deltoid ligament. In addition, the examiner should palpate the distal fibula, medial malleolus, base of the fifth metatarsal, cuboid, lateral process of the talus (to assess for a possible snowboarder’s fracture), and epiphyseal areas to assess for any potential fractures [10,11]. The patient should be examined for strength deficits, or reflex abnormalities, which could reveal concurrent injury. Although it is uncommon, ankle inversion injuries are sometimes associated with peroneal nerve injury and may result in sensory changes on the dorsum of the foot (superficial peroneal nerve) or the first web space (deep peroneal nerve). Deep peroneal nerve injury could result in decreased strength in dorsiflexion and eversion. If a fracture is not suspected, single-leg balance could be tested to assess the extent of proprioceptive compromise.

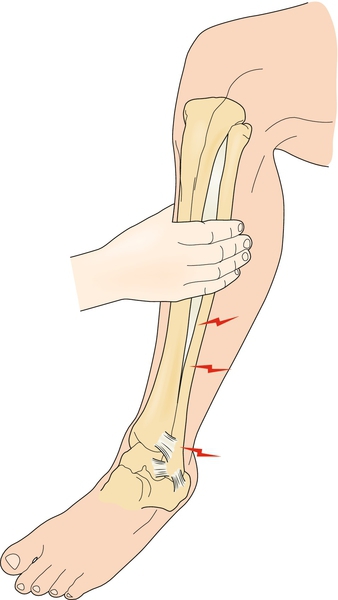

Ankle stability should be examined through a variety of tests and compared with the noninjured side to assess the amount of abnormal translation in the joint. The anterior drawer test of the ankle will assess the integrity of the anterior talofibular ligament. It is performed by plantar flexing the ankle to approximately 30 degrees and applying an anterior force to the calcaneus while stabilizing the tibia with the other hand. Increased translation compared with the other side implies injury to the anterior talofibular ligament. Studies in cadavers suggest that the test is accurate in detecting abnormal lateral ankle motion, with 100% sensitivity and 75% specificity [12,13]. The talar tilt test (Fig. 83.3) is performed with the ankle in a neutral position and assesses the integrity of the calcaneofibular ligament [13]. The squeeze test (Fig. 83.4) is used to diagnose a syndesmotic injury. It is performed by squeezing the proximal fibula and tibia at the midcalf and causes pain over the syndesmotic area. Similarly, the external rotation stress test is performed by placing the ankle in a neutral position and externally rotating the tibia, leading to pain in the syndesmotic region [14]. Unfortunately, several studies have demonstrated poor correlation between clinical stress test results and the degree of ligamentous disruption [15].

Functional Limitations

The patient may have difficulty in walking secondary to pain and swelling. Proprioception and balance on the injured ankle will be abnormal as noted by greater difficulty with single-leg standing on the injured leg [16]. The athlete will have difficulty with return to play until swelling and pain have diminished and rehabilitation is nearly completed. Incomplete recovery or inadequate rehabilitation may predispose the patient to reinjury [17]. Of note, the single-leg balance test can be helpful in predicting which athletes may sustain an ankle injury during the course of the upcoming season [18]. Chronic ankle sprains can result in mechanical instability, with objective instability or laxity noted on examination in all patients [19].

Diagnostic Studies

Standard anteroposterior, mortise, and lateral radiographs should be considered in cases in which there is tenderness over the lateral malleolus, ankle joint, syndesmosis, or other bony structure to rule out an underlying fracture [6,10]. The Ottawa ankle rules were developed and validated to clarify the indications for these ankle radiographs. The rules recommend imaging when there is tenderness along the lower 6 cm of the tibia or fibula, the navicular, or the fifth metatarsal head and an inability to bear weight immediately after injury and in the emergency department. Adherence to these rules has shown a 30% reduction in radiography use while missing no major fractures [10,11]. At 4 to 6 weeks, a slowly healing lateral ankle injury without significant pain resolution or improvement should be evaluated radiographically, especially if an initial radiograph was not obtained.

A magnetic resonance imaging scan can help identify the soft tissue disease as well as evaluate the osteochondral joint surface when the ankle does not heal despite adequate rehabilitation. Osteochondral injuries may not be seen immediately but occur later, especially in cases with chronic instability. Stress radiographs are optional and have questionable reliability because of the great range of normal joint movement [20]. Ultrasonography may be used to further evaluate the soft tissue structures of the ankle, including ligament injury and associated tendon subluxation. Advantages of ultrasonography include the lack of radiation and relatively low cost [21].

Treatment

Initial

Protection, relative rest, ice, compression, and elevation (PRICE) are the proposed mainstay of initial treatment and are introduced immediately [22]. However, there appears to be insufficient evidence to determine the true effectiveness of RICE for acute ankle sprains [23]. It intuitively makes sense to use crutches if weight bearing causes pain. The crutches can be discontinued as ambulatory pain declines (usually in 2 to 3 days). Grade II and grade III sprains may require longer use of assistive devices. Patients should be cautioned to avoid hanging the ankle in a plantar flexed position because it may stretch the injured anterior talofibular ligament. Positioning in maximum dorsiflexion also minimizes resultant joint effusion. Plastic removable walking cast boots or air splints are occasionally used in higher grade injuries until pain-free weight bearing is achieved. These may be used for weeks to months, depending on the extent of injury. Caution should be taken with prolonged immobilization as a systematic review of randomized controlled trials suggests that prolonged immobilization (more than 4 weeks) is less effective than early functional treatment [24]. Local ice applications for 20 to 30 minutes three or four times daily combined with compression immediately after injury is effective in decreasing edema, pain, and dysfunction. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be employed to decrease pain and inflammation. Other therapeutic modalities, including diathermy, electrotherapy, and therapeutic ultrasound, have not been shown to be effective.

Rehabilitation

The rehabilitation of ankle sprains has moved toward earlier mobilization in hopes of minimizing swelling, decreasing pain, and preventing chronic ankle problems [25,26]. Active range of motion in all planes is initially performed without resistance as soon as tolerated. Dorsiflexion and eversion strengthening can be started with static exercises and progress to concentric and eccentric exercises with tubing when the patient tolerates pain-free weight bearing. Double-leg toe raises should progress to single-leg toe raises and can be done in water if they are not tolerated on land. Endurance and lower extremity muscle strengthening exercises are incorporated and increased as tolerated by the patient. Proprioception training can start in a seated position and then advance to standing balance exercises. Standing exercises begin with single-leg stance while swinging the raised leg. Then, single-leg squats are required. Finally, exercises progress to single-leg stance and functional or sport-specific activity, such as dribbling, catching, or kicking. A more recent randomized study comparing PRICE therapy with early mobilization in patients with grade I or grade II ankle sprains reported better functional recovery in the first 2 weeks after injury in the early mobilization groups. There were no long-term differences at 16 weeks, and reinjury rate was the same for both groups [25]. A supervised program appeared to provide better results than a conventional home program [27].

Several studies have highlighted the importance of proprioceptive training in early recovery from ankle sprains and chronic functional instability. The study by Bahr and Bahr [28] of volleyball players demonstrated a 21% reduction in ankle sprains the first year and 49% reduction the second year in athletes who performed balance exercises. In addition, they reported fewer recurrent ankle sprains, and patients with more than one sprain benefited the most. A systematic review by McKeon and Hertel [29] showed that proprioceptive and balance training does in fact improve recovery acutely and can reduce recurrence rates of injury. Therefore, proprioceptive and balance exercises should be incorporated into the rehabilitation program as soon as possible.

The use of orthotic bracing is somewhat controversial. Earlier studies have suggested that bracing and taping may decrease recurrent injury rates in the previously injured ankle, but they have not been shown to be effective in athletes without a prior injury [30,31]. Beynnon and colleagues [30] studied 182 patients with first-time grade I and grade II ankle ligament sprains and showed that treatment with the air stirrup brace combined with an elastic wrap provided earlier return to preinjury function than with use of the air stirrup brace alone, an elastic wrap alone, or a walking cast for 10 days. Interestingly, a more recent meta-analysis suggests that the use of an ankle brace or ankle tape has no effect on enhancing proprioception in individuals with recurrent ankle sprains or who have functional ankle instability [32]. These studies suggest that the decrease in injury rates is due to something other than enhanced proprioception of the ankle.

Despite these findings, many athletes will consider using a brace to prevent a recurrent sprain. A study by Putnam and coworkers [33] suggested that use of ankle braces in healthy competitive recreational soccer players did not significantly affect performance in speed, agility, or kicking accuracy. The authors proposed the need for future studies to investigate the impact on athletes with ankle injuries.

Procedures

Procedures are generally not indicated for ankle sprains.

Surgery

Surgery is rare for ankle sprains. Most grade III ankle sprains with complete tears of the anterior talofibular ligament and instability are not treated surgically unless they result in chronic instability. If necessary, surgical repair may be completed after the sports season and is usually successful. Reconstruction of the lateral ankle ligaments involves anatomic reconstruction of the ligament (modified Brostrom) and tendon weaving through the fibula (Watson-Jones, Chrisman-Snook) [34]. The direct repair of the ligament, even years after the injury, can be highly successful. Despite the various techniques, an extensive literature review recommended the need for randomized controlled studies to determine the relative effectiveness of surgical and conservative treatment for acute injuries of the lateral ligament complex of the ankle [35].

Potential Disease Complications

Recurrent sprains may lead to both mechanical (gross laxity) and functional (giving way) instability. The patient may present with undiagnosed secondary sources of pain, and these must be sought (see the section on differential diagnosis). Chronic intractable pain is another potential complication.

Potential Treatment Complications

Lack of recognition of and the prevalence of subacute sequelae in ankle sprains may lead to undertreatment and subsequent chronic pain or instability. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may cause gastric, hepatic, or renal complications. Prolonged immobilization can lead to inflexibility, muscle atrophy, and longer time loss from work or sport. Return to work, sport, or activity before adequate healing and rehabilitation may result in chronic pain and giving way (functional instability) and gross laxity (mechanical instability). As noted, heat and contrast baths should be avoided during the acute stage of injury as these modalities could promote swelling and bleeding. Finally, surgical complications could include joint injection, loss of range of motion, and compromised gait.