CHAPTER 82

Ankle Arthritis

David Wexler, MD, FRCS (Tr & Orth); Dawn M. Grosser, MD; Todd A. Kile, MD

Definition

Ankle arthritis is degeneration of the cartilage within the tibiotalar joint that can result from a wide range of causes, most commonly post-traumatic degenerative joint disease. An acute injury or trauma sustained a number of years before presentation or less severe, repetitive, minor injuries sustained during a longer period can lead to a slow but progressive destruction of the articular cartilage, resulting in degenerative joint disease [1]. Other common types are primary osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis (including rheumatoid, psoriatic, and gouty), and septic arthritis. Osteoarthritis is usually less inflammatory than rheumatoid arthritis but can also involve many joints simultaneously.

Symptoms

As with arthritis of any joint, the presenting symptoms are pain (which may be variable at different times of the day and exacerbated by activity), swelling, stiffness, and progressive deformity [1]. The ankle may be stiff on initial weight bearing; this improves after walking a while but then worsens with too much ambulatory activity. The pain is often relieved with rest. Pieces of the cartilage can break off, forming a loose body, and the joint can “lock” or “catch,” sticking in one position and causing acute, excruciating pain until the loose body moves from between the two irregular joint surfaces. Another symptom is that of “giving way” or instability of the joint, which may be a result of surrounding muscle weakness or ligamentous laxity. With progression of the arthritis, night pain can become a major complaint.

Physical Examination

Swelling, pain, and possibly increased temperature on palpation may be present. The pain is usually maximal along the anterior talocrural joint line and typically chronic and progressive. If the patient’s other ankle is normal, it is important to compare the two. Deformity and reduced range of motion in plantar flexion and dorsiflexion (normal: up to 20 degrees of dorsiflexion and 45 degrees of plantar flexion) may be seen. The patient may exhibit an antalgic gait or a limp. Acute arthritis is manifested very differently. Onset is rapid with associated warmth, erythema, swelling, and severe pain with passive range of motion and may be accompanied by constitutional symptoms such as fever and rigors.

It is appropriate to examine the other joints in the lower limb, particularly the knee. The findings on neurovascular examination are typically normal. Decreased sensation in the lower limb raises the possibility of a Charcot joint causing a destructive arthropathy (see Chapter 128).

Functional Limitations

Pain with walking distances and difficulty in negotiating stairs or inclines are particular functional disabilities. Even prolonged standing can become intolerable with advanced joint deterioration. Night pain can lead to disturbance of sleep. Patients will typically adjust their activities or eliminate many of them, particularly exercising, because of pain.

Diagnostic Studies

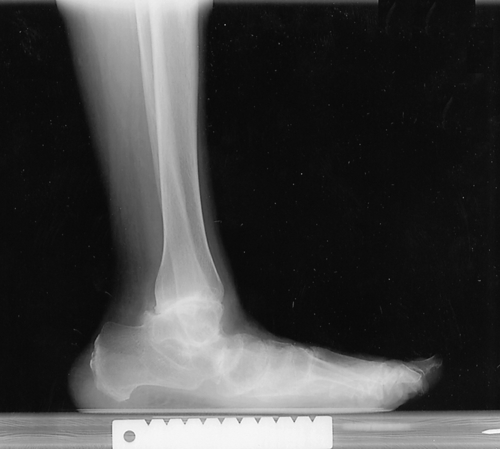

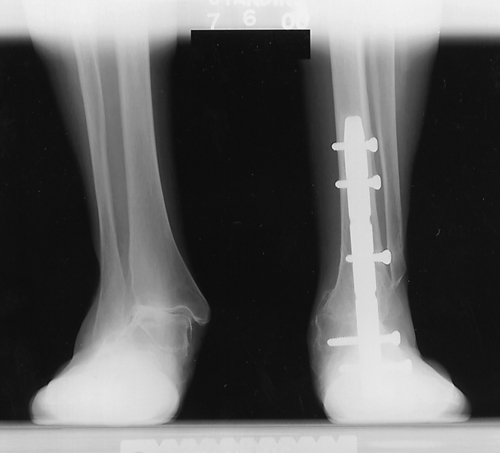

Plain anteroposterior and lateral standing radiographs provide sufficient information in the later stages of the disease (Figs. 82.1 and 82.2). Magnetic resonance imaging may show damage to articular cartilage and a joint effusion earlier in the course of the disease. In assessment of the radiographs, attention should also be paid to the other joints in the hindfoot because these will affect management options. Generalized bone density and alignment should also be noted.

In some cases, patients present with varying degrees of degeneration of other, adjacent joints, such as the subtalar joint or the knee. By performing differential blocks (i.e., isolated ankle block or subtalar block) with local anesthetic under radiographic control, the clinician may determine which of these joints are symptomatic. A bone scan might be of assistance. In acute presentations, complete blood cell count with a white blood cell count differential, serum urate concentration, and possible joint needle aspiration can help clarify the diagnosis.

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment focuses on pain relief and minimizing inflammation. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or simple analgesics are used to alleviate the pain. Prefabricated orthoses ranging from flexible neoprene braces and lace-up or wraparound ankle supports to more rigid braces or walking boots can be prescribed to enhance stability and to reduce movement in the ankle joint, thus reducing pain levels.

Rehabilitation

A custom-molded rigid ankle-foot orthosis fabricated by a skilled orthotist along with a rocker-bottom modification to the shoe (which can be accomplished by most cobblers) can provide dramatic pain relief for most patients with ankle arthritis. A physical therapist can instruct a patient in the proper technique for use of a walking stick or cane in the opposite hand. This is a simple but effective aid in reducing the forces across the ankle joint when the patient is ambulatory.

Mobilization, stretching techniques, and range of movement exercises may help alleviate pain and stiffness. Non–weight-bearing exercises are important, and if it is accessible, hydrotherapy has been shown to be an extremely useful and productive adjunct. Distraction and gliding mobilization techniques improve range of movement. Strengthening of surrounding muscle groups and proprioceptive rehabilitation will enhance stability.

Procedures

Other than the blocks that are performed to determine the location of the pathologic changes in confusing cases, injections are not typically done for ankle arthritis. Corticosteroid injection is generally of only limited duration, and steroids are chondrotoxic (cause cartilage damage). However, they can provide excellent temporary pain relief in patients with joints at end-stage disease. Viscosupplementation injections (as used in the management of knee arthritis) are still experimental and not recommended at this time.

Surgery

Surgery is indicated in patients who fail to respond to nonoperative management and especially in those with unremitting pain. In the earlier stages of arthritis, an arthroscopic washout and cartilage débridement of the ankle joint may provide significant improvement in pain levels.

As the disease progresses, more extensive surgery is required. Many different variations and techniques of fusion have been described, ranging from minimally invasive arthroscopic arthrodesis to open fusion with hardware [1–6]. Distraction arthroplasty (application of an external fixator for a period of time) has shown some promising results. Total ankle joint replacement (arthroplasty) has been an alternative to ankle fusion since the 1970s in certain select populations of patients. It has undergone a series of alterations because the earlier generation models were prone to failure and unpredictable results [7]. In recent times, there have been significant advances in and ongoing research comparing efficacy of arthrodesis and total joint arthroplasty [8,9]. Selection of patients is of paramount importance; those with high expectations and demands (hiking, tennis, running) may be better served with a more predictable, stable fusion than with a replacement that has a high likelihood of failure and need of revision.

Potential Disease Complications

Progressive immobility, permanent loss of motion of the ankle joint, bone collapse leading to leg length discrepancy, and chronic intractable pain can result from ankle arthritis.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Arthroscopy can be complicated by nerve damage or, rarely, septic arthritis. On occasion, with arthrodesis, fusion can fail to occur [10]. An alteration in gait is common [11]. Arthroplasty complications include infection, thromboembolism, bone collapse, and implant migration.