CHAPTER 81

Achilles Tendinopathy

Definition

Achilles tendinopathy exists along a spectrum of peritendinitis to tendinosis or tendinopathy. The pathologic process involves a painful, swollen, and tender area of the Achilles tendon and peritenon. Athletes with particularly tight heel cords are predisposed to this injury. This condition commonly affects middle-aged men who play tennis, basketball, or other quick start-and-stop sports. Achilles tendon rupture carries a 200-fold risk of sustaining a contralateral rupture of the Achilles tendon [1], but atraumatic disease associations, such as periarticular manifestation of poststreptococcal reactive arthritis [2], should remain in the atraumatic differential. Collagen vascular disease, inflammatory disease, and diabetes may also be risk factors. The relative avascularity of the region 5 to 7 cm proximal to the calcaneus insertion has long been considered a pathoanatomic structural risk factor, as is the thinning and twisting of the tendon at this midsection [3]. However, morphologic and biochemical differences present within the tendon during Achilles tendinopathy provide a modern addendum to this dogma. Upregulation of collagen 1 and collagen 3 together with mRNA of fibronectin, tenascin C, and fibromodulin as well as degradation factors matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 2 in Achilles tendinopathy [4] seem to add to the growing understanding of the cellular and molecular basis of the clinical presentation. The histopathologic feature is angiofibroblastic hyperplasia (tendinosis) of the body of the tendon (a degenerative process) with a concomitant and potentially secondary inflammatory response in the peritenon [5,6]. The maladies often occur simultaneously but may occur individually. An association with chronic quinolone exposure is well documented [7–9] and is worse in patients concomitantly taking prednisone long term.

Symptoms

Pain and tenderness in the Achilles tendon are predominant symptoms, usually in association with running, sports with quick “cutting,” and other fitness activities [10]. Activities with rapid starting and stopping or rapid eccentric contraction, such as classical ballet [11], increase the symptoms and risk of complete tear. In some patients, the pain actually improves with lower extremity exercise. Typically, the pain occurs with a change in activity or training schedule. The most common location for tendinosis symptoms is at the apex of the Achilles tendon curvature. Different activities can lead to pathologic change in other regions of the tendon, namely, at the calcaneal insertion with or without a Haglund deformity or at the myotendinous junction. A history of an acute traumatic event in which the patient reports a “pop” should suggest an Achilles tendon tear, although a similar pop can occur with tear or rupture of the plantaris, peroneus, or posterior tibial tendon. History of quinolone exposure, diabetes, collagen vascular disease, anabolic steroid use, or smoking should be noted.

Physical Examination

The essential element in the physical examination is localization of swelling and tenderness in the critical zone of the Achilles tendon at the apex of the Achilles curve approximately 2 1⁄2 inches proximal to the os calcis insertion. Exquisite tenderness to palpation is a classic examination finding. The degree of ankle plantar force generated has been shown to have a strong negative relationship with pain, and a standardized strength testing system has been suggested and shown to be reliable on a small sample of patients [12]. Palpable heat is usually not evident unless peritendinitis is a major component. The Achilles tendon is usually tight, with ankle dorsiflexion rarely extending beyond 90 degrees. Associated findings may include abnormal foot posture (pes planus or cavus), tight hamstrings, and muscle weakness of the entire hip and leg. Heels may not move into a normal varus position in standing on toes. Neurologic evaluation findings, including strength, sensation, and deep tendon reflexes, are normal.

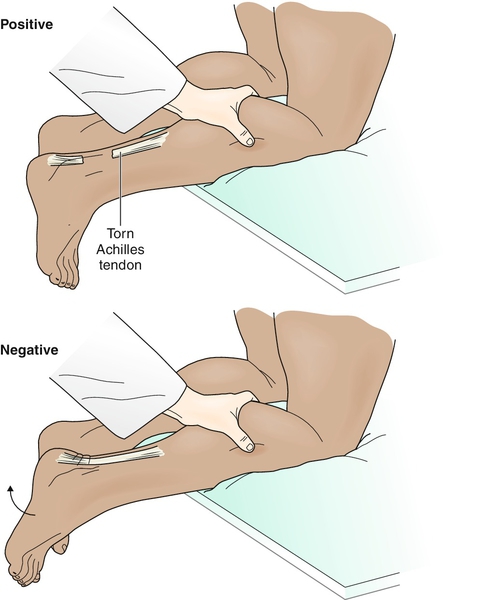

The examination should also include observation for a palpable defect and the Thompson test (squeezing the calf, which should result in plantar flexion in an attached tendon) to rule out rupture of the Achilles tendon (Fig. 81.1).

Functional Limitations

Impact weight-bearing activities, such as jogging and running, are usually limited. Dance or cutting “moves” typical of field sports are virtually impossible. Nonimpact fitness activities, such as cycling and using an elliptical trainer, may also result in symptoms. Patients may complain of pain with daily ambulatory activities, such as walking at work or climbing stairs. Whereas individual differences exist, early recovery of plantar flexion may be seen with little functional change, usually because of flexor hallucis longus compensation [13].

Diagnostic Studies

Unless a special form of calcified Achilles tendinosis occurs at the os calcis insertion, regular radiographs are usually normal. Diagnostic ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging is capable of defining the extent of both tendinosis and peritendinitis, but serial magnetic resonance examinations, especially postoperatively, are not indicated and do not correlate with functional outcome [14]. Partial rupture is a diagnostic dilemma for diagnostic ultrasonography [15], and if it is suspected, magnetic resonance imaging should still be considered the standard of care. Magnetic resonance imaging is also more useful in documenting a complete tear’s distance and location as well as the existence of partial tear that may appear normal or questionable on diagnostic ultrasound examination. Electrodiagnostic studies, especially needle electromyography and H reflexes (the electrodiagnostic equivalent of an Achilles muscle stretch reflex), may help in defining S1 radicular features, but a normal electrodiagnostic study does not rule out sensory irritative radiculitis. These studies are generally recommended only to help define the prognosis or in patients who are unresponsive to rehabilitation and for whom surgery or other diagnoses are being considered. A slowly evolving role of positron emission tomography may exist [16], and blood work germane to systemic disease, sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and antistreptolysin antibody titer [2] may be appropriate.

Treatment

Initial

The initial treatment goal is to decrease pain and to reduce inflammation when it is present. Therefore rest from aggravating activities is critical. Icing (20 minutes, two or three times daily) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or analgesics can be used for pain and inflammation. A wide range of treatments from repetitive low-energy shock wave treatment [17], sclerosing agents [18], and topical nitroglycerin [19] to low-level laser therapy have been attempted with varying degrees of mixed results in small studies.

Counterforce bracing is often helpful, or a simple heel lift (1⁄8 to 1⁄2 inch) can decrease stress on the tendon. Warm-up before any weight-bearing activity and cooling with ice afterward are recommended. Good functional results can usually be achieved in about 75% of cases at 3 months with nonoperative treatment in compliant patients with a tendon separation distance of 10 mm or less apparent on diagnostic ultrasonography [20].

Rehabilitation

The rehabilitative process focuses on biologic improvement of the damaged tendon and peritenon and restoration of function, rather than the comfort efforts of the initial treatment phase. Rehabilitation is best initiated in a structured physical therapy program followed by home therapeutic exercise. Non–weight-bearing status and axillary crutches may have a role in the acute phase of treatment, with return to weight bearing as tolerated. A short leg cast or splint in 10 to 15 degrees of plantar flexion may also have a short-term role in acute phase treatment. Passive modalities including therapeutic ultrasound, iontophoresis, and phonophoresis often enhance compliance and enable the rehabilitation program. Electrical stimulation should be considered contraindicated in the face of the overuse etiology and counterphysiologic motor unit recruitment of muscle fibers.

Therapeutic exercise needs to be directed toward the complete kinetic chain because strength, endurance, and flexibility deficits are common, and most lower extremity sports activities occur as patterned motor engrams. Strength, proprioceptive, and endurance testing usually aids in uncovering relative weaknesses and monitoring the rehabilitation progress. Controlled eccentric exercise may be of benefit throughout the strength-building phase of rehabilitation and avoid additional tendon separation.

Control of abusive force loads can be accomplished by counterforce bracing of the Achilles tendon or orthotics to minimize abnormal foot posture. Gradual, controlled return to running may be initiated through running in water programs. As with any lower extremity injury, general fitness may be maintained by use of upper body land programs such as arm ergometry, resistance training, and water programs dedicated to the entire body. Return to sport or running is transitional, including plyometric and eccentric exercises. Full return generally requires normal strength, endurance, and flexibility. Repeated injury is not uncommon. Return to normal activity, generally in 6 to 12 weeks, depends on level of participation (professional athlete versus weekend warrior), severity of the injury, and general medical condition.

Procedures

Exogenous glucocorticoid injection is contraindicated as cellular death and tendon weakness with potential progression to tendon rupture are significant concerns. Although there may be a developing role for hylan G-F 20 [21], this has been studied, to date, only in corticosteroid-induced Achilles tendinopathy in an animal model. Likewise, pulsed ultrasound [22], indium-gallium-aluminum-phosphide diode laser irradiation [23], and substance P injection [24] in an animal tenotomy model have all shown potential results, and hyperbaric oxygen [25] may have a slightly more promising role.

Surgery

Rehabilitation failure may invite surgical intervention with a goal of problem resolution versus acceptance of the malady and alteration of activity level. Optimal surgical management strategy is controversial, but the relative avascularity of the region makes wound healing complications and deep infection ever-present threats. The concepts of surgery include removal of symptomatic peritendinitis tissue and resection of the abnormal tendinosis tissue in the body of the Achilles tendon with subsequent repair of the remaining adjacent normal tendon. This is usually accomplished with standard sutures or wires; however, fibrin sealant has been used [26], and at least on the surface, this may seem a more biologic approach. Surgical options consist of open, mini-open, or percutaneous repair. Surgery outcomes are better if all pathologic tissue is removed, reanastomosis is performed, and appropriate postoperative rehabilitation is implemented. The postoperative goals of neovascularization, reduction of atrophy, fibroblastic infiltration, and collagen production and the restoration of strength, endurance, and flexibility are best served by early mobilization [27].

In cases of suspected tendon rupture, a surgical consultation is warranted for consideration of other tendon ruptures. Endoscopic techniques have evolved alongside open and mini-open [28] approaches but with comparable re-rupture rates. The percutaneous repair seems to be a better option for elite athletes with a greater likelihood of return to sport activities [29], but it has an increased complication rate. There are differences of opinion as to whether the percutaneous technique should be performed at all in lieu of a limited open technique [30].

Potential Disease Complications

Chronic symptoms can result in weakening and subsequent complete rupture of the Achilles tendon. Chronic intractable pain with other kinetic chain imbalances and secondary gait abnormality may develop. Significant alterations in gait can cause secondary knee, hip, forefoot, or low back pain. Consideration of undiagnosed systemic diseases that carry their own comorbidities should be entertained.

Potential Treatment Complications

Side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs include gastric, renal, and hepatic complications. Bracing for prolonged periods may lead to pressure sores, disuse weakness, atrophy, poorly coordinated motor control when return to activity is attempted, and potential peroneal neuropathy. Sural nerve injury can occur with open or percutaneous repair [31]. Overly aggressive physical therapy or electrical stimulation of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex may cause increased pain and inflammation that can ultimately lead to tendon weakness and potential rupture. Surgical complications of bleeding, infection, and tibial, peroneal, or sural nerve injury are well known. Repeated tear may occur.