Case 8 Migraine

Description of migraine

Definition

Migraine is a complex neurovascular disorder characterised by episodic headaches. The two major categories of migraine are classic migraine (i.e. migraine with aura) and common migraine (i.e. migraine without aura). Other variants of the disorder are chronic migraine (i.e. producing ≥15 attacks per month), hemiplegic migraine (i.e. associated with defects to chromosomes 1, 2 and 19) and basilar artery migraine (i.e. caused by vertebrobasilar ischaemia).1,2

Epidemiology

Migraine typically begins in adolescence. The prevalence of the condition increases from this point, peaking around age 40 and declining thereafter. In the US, migraine affects around eighteen per cent of women and six per cent of men.3 The higher prevalence rate reported in the female population is evident across all age groups, except for the prepubescent period, in which migraine is relatively more common in males. Migraine is also more prevalent among Caucasians, particularly Europeans and Americans; it is least prevalent in the African and Asian populations.3

Aetiology and pathophysiology

The aetiology and pathophysiology of migraine are complex and still not completely understood. Genetic predisposition is likely to be a contributing factor, although not all cases have a familial tendency.4 Even though specific causes of migraine have yet to be established, a number of triggers have been identified. Intrinsic triggers, such as oestrogen fluctuation, brain serotonin depletion, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, emotional stress, excessive or inadequate sleep and neck pain, as well as extrinsic triggers such as tyramine-containing foods (i.e. cheese, red wine, chocolate, preserved meats), monosodium glutamate, weather changes (such as increased temperature or elevated barometric pressure), head trauma, hormone therapy, oral contraceptive use, strong odours, intense or flashing light and skipped meals, have all been associated with the onset of migraine.1,2,5 It is also suggested that nutritional deficiency, specifically, magnesium deficiency, could play a role in the pathogenesis of migraine.6–8

Genetic predisposition and/or risk factors as yet unknown may lower an individual’s threshold to these triggers, upon exposure to which, susceptible individuals may experience a reduction in cerebral blood flow, which, in some people, may manifest as an aura. The cortical spreading depression (CSD) of blood flow from the occipital lobe to other regions of the cerebral cortex, which may be preceded by brain serotonin depletion, triggers the diffuse activation of perivascular trigeminal sensory nerves.5 These impulses are transmitted to the trigeminal nucleus caudalis of the brainstem and from there to the periaqueductal grey matter, sensory thalamus and sensory cortex. The stimulation of these regions results in the manifestation of pain.2,4

There are several deviations from this theory, however. Some argue that the pain of migraine is simply a rebound vasodilatatory response to CSD. Others propose that the activation of the trigeminovascular system increases neuropeptide release, which results in painful inflammation to the dura mater and cranial vessels.1 Still others have also indicated that migraine may be the result of mitochondrial dysfunction and a subsequent impairment in cellular oxygen metabolism.9 While researchers do not completely agree on the pathophysiology of migraine, there is general agreement that migraine is a neurovascular disorder.

Clinical manifestations

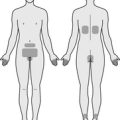

The International Headache Society (IHS) defines migraine as a repeated, episodic headache of 4–72 hours duration that is characterised by any two of the following: unilateral distribution, throbbing quality, moderate or severe intensity and/or worsened by movement. To complete the IHS criteria, the pain also should be accompanied by nausea and vomiting, or photophobia and phonophobia.4 It is not unusual for individuals with migraine to also experience osmophobia, poor concentration, blurred vision, clumsiness, localised weakness, numbness or tingling, irritability and scalp tenderness.1,2

In cases of classic migraine, the headache is preceded by a temporary neurological disturbance known as an aura. This phenomenon typically presents as a visual defect (e.g. bright zigzags, scintillating lights), but may also manifest as a sensory or motor disturbance (e.g. paraesthesias, dysarthria, ataxia, confusion).2 Hemiplegic migraine generally presents as unilateral weakness, and basilar artery migraine as focal weakness, vertigo, ataxia and altered consciousness.1 The symptoms of migraine are often aggravated by bright lights, noise, strong odours and physical activity, and are somewhat relieved following seclusion in a dark, quiet environment.1

Clinical case

35-year-old woman with classic migraine

Rapport

Adopt the practitioner strategies and behaviours highlighted in Table 2.1 (chapter 2) to improve client trust, communication and rapport, as well as the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the clinical assessment.

Medical history

Family history

Mother suffers from migraine headaches, grandfather has Parkinson’s disease.

Lifestyle history

Illicit drug use

| Diet and fluid intake | |

| Breakfast | Black tea, white English muffin with butter. |

| Morning tea | Apple, banana, orange. |

| Lunch | White wrap with lettuce, cheese, chicken and avocado, quiche with mixed green salad. |

| Afternoon tea | Black tea, mixed nuts (e.g. almonds, cashews, Brazil nuts). |

| Dinner | Grilled whiting or chicken breast with steamed carrots, beans and potato au gratin, cream of chicken soup or potato and leek soup with white bread. |

| Fluid intake | 2–4 cups of black tea a day, 2–3 cups of water a day. |

| Food frequency | |

| Fruit | 1–2 serves daily |

| Vegetables | 2–4 serves daily |

| Dairy | 2–3 serves daily |

| Cereals | 3–4 serves daily |

| Red meat | 0–1 serve a week |

| Chicken | 3 serves a week |

| Fish | 1–2 serves a week |

| Takeaway/fast food | 0–1 time a week |

Socioeconomic background

The client was born in Canada, as was her mother. Her father was born in France. Upon completing her social work degree 13 years ago, the client moved interstate and took up residence in an inner city apartment. The client has seen very little of her parents and siblings since the move, which upsets her at times. The client works in a general hospital as a senior social worker and, while she enjoys her chosen career and the company of her work colleagues during and outside normal working hours, the work is very demanding and stressful. The client is single with no children and there are no notable religious or cultural beliefs to report.

Diagnostics

Pathology tests

Magnesium deficiency test

Magnesium deficiency may be implicated in the pathogenesis of migraine.6–8 Intracellular and/or extracellular magnesium concentration may be measured using a range of different specimens – hair, erythrocytes, serum, urine and faeces. While some authorities indicate that erythrocytic magnesium concentration may be more sensitive than other methods in measuring magnesium levels,10 there has been little rigorous research to substantiate this argument. In fact, studies suggest that hair magnesium may be a more sensitive measure of magnesium concentration than erythrocytic magnesium, and serum magnesium the least sensitive.11 Thus, assessing hair or erythrocytic magnesium concentration may help to determine whether magnesium deficiency is a contributing factor in this condition.

Miscellaneous tests

Electroencephalogram (EEG) measures the electrical activity of the brain by placing electrodes on an individual’s scalp. The abnormal frequency, characteristics and amplitude of these brain wave patterns, either at rest or following stimulation, may indicate the presence and location of epilepsy. An EEG may be indicated if epilepsy is believed to be masquerading as migraine.12

Diagnosis

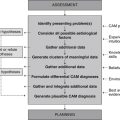

Planning

Goals

Expected outcomes

Based on the degree of improvement reported in clinical studies that have used CAM interventions for the management of migraine,13–17 the following are anticipated:

Application

Diet

Low antigenic diet (Level II, Strength C, Direction + (for oligoantigenic diet only))

Tyramine-containing foods, such as cheese, red wine, chocolate and preserved meats, and food additives such as monosodium glutamate, are considered to be key dietary triggers of migraine headache.1,2 Even though many studies have explored the relationship between these triggers and the onset of migraine, the evidence is not convincing. Several dietary studies have, for instance, reported a large reduction in migraine frequency during the consumption of an oligoantigenic diet and the provocation of migraine attacks following double-blind challenges with suspected dietary triggers.18–20 These findings should be considered with caution given the small size of the studies and the lack of corroborating evidence from larger trials.

Several controlled clinical trials have also demonstrated an increased incidence of migraine attacks following the consumption of low tyramine-containing red wine21 and aspartame22 when compared with controls, but many studies have failed to find a statistically significant difference in migraine frequency in groups receiving tyramine,23 chocolate24 or a low vasoactive amine diet25 when compared with controls. This is corroborated by findings from a systematic review of 10 RCTs exploring the relationship between oral ingestion of biogenic amines and food intolerance reactions.26 The discrepancies between these research findings and those reported in the professional literature need to be resolved to minimise clinician confusion about the best practice care of migraine.

Lifestyle

Guided imagery (Level II, Strength B, Direction o)

Guided imagery is a mind–body technique that requires an individual to visualise images and/or imagine tastes, smells, sensations and sounds in order to induce relaxation, facilitate healing and/or alter behaviours and thoughts. This suggests that guided imagery could help to reduce migraine frequency by alleviating emotional stress, a known trigger of migraine. Two RCTs have explored this hypothesis, with mixed results. The trial by Brown27 compared two different guided imagery approaches to a subconscious reconditioning control (5 × 1-hour sessions over 4 weeks) in 39 adults with migraine headache. The improvement in composite headache score (i.e. changes in headache frequency, duration, intensity and headache-free days) at 4 weeks significantly favoured guided imagery over control. Ilacqua28 found no statistically significant difference between guided imagery, psychosynthetic approach or biofeedback and control in reducing migraine activity after six sessions of training. Subjects receiving guided imagery or mind–body therapy did report an increased capacity to cope with pain, as well as a reduced perception of pain when compared with subjects receiving control. Even so, changes in medication use between groups were not statistically significant in either study. The evidence of effectiveness for guided imagery and migraine can thus be said to be inconclusive.

Meditation (Level II, Strength C, Direction +)

Meditation is a mind–body therapy that uses a diverse range of techniques, such as mindfulness, breathing, concentration, visualisation, mantras and/or affirmations, to bring about inner tranquillity and/or improve self-awareness. A 1985 report of three cases highlighted the possible benefit of meditation in reducing migraine headache,29 but it was not until more recently that the use of meditation for migraine was examined under randomised controlled conditions. The RCT compared the effects of three meditative techniques – spiritual meditation, internally focused secular meditation and externally focused secular meditation – to muscle relaxation in 83 meditation naïve migraine sufferers. After 4 weeks of treatment for 20 minutes a day, spiritual meditation was found to be statistically significantly more effective than the other three interventions in reducing headache frequency and pain tolerance, but not headache severity.30 Whether other forms of meditation are any more effective than spiritual meditation in improving migraine symptoms is yet to be determined.

Relaxation therapy (Level I for children, Level II for adults, Strength C, Direction +)

Relaxation therapy describes a collection of mind–body techniques that induce the relaxation response, which in turn lessens sympathetic nervous system activity. Utilising these techniques in the management of migraine has been an area of much study over the past three decades, most of which has been conducted in children,31,32 though a few clinical trials were conducted in adults.33,34 Evidence from these trials is generally consistent. It indicates that relaxation therapy either alone (e.g. progressive muscle relaxation, breathing exercises) or in combination with other behavioural techniques (e.g. stress management, biofeedback, cognitive training) is significantly superior to controls (e.g. metoprolol, physical therapy, waiting list, attention control, neutral writing) in reducing migraine severity, particularly headache frequency, immediately after treatment and at follow-up. Although the best available evidence is in favour of relaxation therapy, the real challenge for clinicians, given the heterogeneous treatment durations, outcome measures and treatment combinations used, will be to apply these findings to clinical practice.

Yoga (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Yoga is an ancient Indian practice that integrates stretching, exercise, posture and breathing with meditation. Given that these techniques are likely to induce a relaxation response, yoga may be helpful in alleviating stress-induced migraine. Two RCTs have examined the effectiveness of yoga in people with common migraine (n = 72)14 and migraine or tension headache (n = 20).16 Both trials reported a statistically significant improvement in headache activity (i.e. migraine intensity and frequency) and symptomatic medication use following yoga therapy when compared with controls at 3–4 months. Both studies are, though, considered to be at moderate risk of bias because of insufficient detail relating to allocation concealment and intention-to-treat analysis.

Nutritional supplementation

Coenzyme Q10 (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Defective energy metabolism, secondary to mitochondrial dysfunction, is implicated in the pathogenesis of migraine.9 Thus, substances that improve mitochondrial function, such as CoQ10, may play a role in migraine prevention. Several open-label trials suggest CoQ10 supplementation (150 mg daily for 3 months) may be effective in reducing the frequency and duration of attacks in people with migraine;35,36 evidence from a double-blind RCT corroborates these findings.37 The trial involving 42 migraine sufferers found that CoQ10 supplementation (300 mg daily) for 3 months was significantly more effective than placebo in reducing migraine frequency and duration, and the number of days with nausea. In fact, the percentage of subjects in each group whose degree of improvement in attack frequency reached or exceeded 50 per cent was 47.6 per cent for the CoQ10 group and 14.4 per cent for the placebo group. These positive findings now require replication in larger trials.

Magnesium (Level II, Strength B, Direction + (for magnesium citrate and magnesium oxide only))

Magnesium is involved in many enzymatic reactions and physiological processes throughout the body. While its role in migraine is not clear, it is suggested that migraine may be a magnesium deficiency disease, with several studies demonstrating comparatively lower levels of brain,7 salivary, serum6,8 and red blood cell magnesium8 in migraine sufferers than non-migraine sufferers. It is plausible, therefore, that magnesium supplementation may improve the symptoms of migraine. According to findings from three double-blind RCTs (n = 201 adults), this appears to be the case, with oral magnesium citrate (600 mg daily) found to be statistically significantly more effective than placebo in reducing migraine frequency.15,17,38 In terms of improving migraine severity, the evidence is mixed. Studies using other forms of magnesium have produced contrasting results. One RCT, involving 118 children and adolescents with migraine, found magnesium oxide supplementation (253.5–760.5 mg daily) for 16 weeks to be superior to placebo in reducing migraine severity, but no more effective than placebo in decreasing migraine frequency.39 An RCT (n = 69 adults) using magnesium aspartate (486 mg daily for 12 weeks) reported no significant difference in the frequency or duration of migraine between those receiving magnesium and those on placebo.40 What these findings reveal is that supplementation with oral magnesium citrate is likely to be effective in migraine prophylaxis and that magnesium oxide may be effective in the treatment of migraine.

Niacin (Level I, Strength C, Direction +)

Vitamin B3 is responsible for a wide range of biological functions. Several of these actions are particularly relevant to migraine management, namely, the ability to dilate intracranial vessels and to maintain adequate mitochondrial energy metabolism.41 Weak evidence from a systematic review of three case reports suggests that orally administered niacin (300–500 mg of variable duration) may reduce headache frequency in people with a history of migraine.41 Despite these findings, all studies were small, lacked controls and were at high risk of bias, which limits any conclusions that can be drawn.

Riboflavin (Level II, Strength B, Direction + (in adults only))

Vitamin B2 is a water-soluble vitamin that plays an important role in cellular respiration, a function that may help to improve mitochondrial energy efficiency and, in so doing, may address the underlying mitochondrial dysfunction associated with migraine.9 Several studies have examined the clinical effectiveness of riboflavin for migraine prophylaxis, with the best available evidence arising from two double-blind RCTs. The first trial found oral riboflavin (400 mg daily for 12 weeks) to be significantly superior to placebo in reducing headache frequency and duration in 55 adults with migraine.42 In children (n = 48), riboflavin supplementation (200 mg daily for 4 weeks) was found to be no more effective than placebo at improving migraine frequency, severity and duration, analgesic use and days with nausea and vomiting.43 Although the latter study indicates riboflavin may not be effective in preventing migraine in children, it is possible that the short treatment duration and lower dose of riboflavin could have influenced the outcomes of the study.

Omega 3 fatty acids (Level II, Strength B, Direction o)

Neurogenic inflammation and subsequent neurogenic vasodilatation are believed to be contributing factors in the pathophysiology of migraine headache.44 Anti-inflammatory agents, such as omega 3 fatty acids,45 may help to attenuate neurogenic inflammation and, in turn, prevent the onset of migraine. In spite of this theoretically plausible hypothesis, evidence from two double-bind RCTs fails to support this theory. Both trials showed oral supplementation of omega 3 fatty acids (2–6 g daily for 8–16 weeks) to be no more effective than placebo (olive oil) in reducing migraine frequency, severity, duration or analgesic use in adults (n = 196)46 and adolescents (n = 27)47 with a history of migraine. These findings should be interpreted with caution as the effect of olive oil in migraine headaches cannot be dismissed as just a placebo effect.

Herbal medicine

Petasites vulgaris (Level I, Strength B, Direction + (for adults only))

Butterbur was traditionally used as a treatment for gastrointestinal, respiratory and urogenital complaints. Evidence of anti-inflammatory and vasodilatory activity in experimental studies suggest this herb may be useful in migraine prophylaxis.13 Evidence from a systematic review of three RCTs (n = 365) concluded that butterbur root extract (100–150 mg daily for 12–16 weeks) was superior to placebo in reducing the frequency of migraine attacks in adults.13 A more recent trial, which involved 58 primary school children, found butterbur to be no more effective than placebo or music therapy at reducing attack frequency at 12 weeks. Interestingly, both butterbur and music therapy demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in attack frequency when compared with placebo at 8 weeks follow-up.48 While the results are promising for adult migraine sufferers, larger trials of longer duration are required before any firm conclusions can be drawn about the efficacy of butterbur in childhood migraine.

Tanacetum parthenium (Level I, Strength B, Direction o)

Feverfew has long been used in the treatment and prevention of migraine headaches. Its use is supported by data from experimental studies that have shown the plant to exhibit analgesic,49 anti-inflammatory50 and vasodilator activity.51 Findings from a Cochrane review of five RCTs (n = 343), and results from a more recent double-blind RCT (n = 170), are mixed in terms of change in global migraine scores, migraine frequency and severity, and nausea and vomiting.52,53 Between study differences in feverfew dosage, method of preparation (including the use of CO2 extracts, dried extracts and ethanolic extracts) and treatment duration (4–24 weeks) also do not allow for the pooling of results, which indicates that the effectiveness of feverfew in the prevention and/or treatment of migraine is inconclusive.

Other

Acupuncture (Level I, Strength B, Direction +)

Acupuncture originated in China more than 4000 years ago.54 This ancient therapy has long been used as a treatment for many acute and chronic conditions, including migraine. Its use as a treatment for migraine is supported by a Cochrane review of 22 RCTs involving 4419 participants. The review found acupuncture treatment to be significantly superior to acute treatment or routine care in reducing headache frequency, headache days and headache scores 3–4 months after randomisation, as effective as prophylactic drug treatment in reducing analgesic use and migraine attacks, and significantly superior to prophylactic drug treatment in improving migraine days and intensity 2–6 months after randomisation. Comparisons with routine care and prophylactic drug treatment could, though, be biased due to inadequate blinding and high dropout rates, respectively. When true acupuncture was compared with sham acupuncture, no statistically significant difference in participant outcomes was observed.55 Given that, in several of the trials, the sham acupuncture technique could not be distinguished from true acupuncture suggests that the sham intervention may not have been physiologically inert, which might have confounded the results.

Chiropractic (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Chiropractic manipulation is generally prescribed for the treatment of musculoskeletal and nervous disorders, including migraine. Three RCTs have explored the effectiveness of chiropractic manipulation in migraine prevention, two of which were reported in a systematic review of the literature.56 Two of the trials found chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) for 8 weeks to be significantly more effective than control in improving migraine frequency, duration, disability and medication use (n = 127)57 and as effective as amitriptyline in reducing headache index scores (n = 218).58 Findings from the latter study should be interpreted with caution as the trial may not have been adequately powered to test for therapeutic equivalence.56 The third RCT (n = 85) measured changes in migraine frequency, duration and disability in groups receiving SMT performed by a chiropractor, SMT provided by a physiotherapist or medical practitioner, or mobilisation control performed by a physiotherapist or medical practitioner.59 No statistically significant differences were found between groups after 6 months of treatment, rendering the effectiveness of chiropractic SMT for migraine inconclusive, although findings from two of the three trials are promising.

Homeopathy (Level I, Strength C, Direction + (for non-classical treatment only))

Homeopathy is a system of medicine that uses highly diluted and potentised remedies to influence the body’s vital force and restore balance. The therapy can be used to treat a wide range of acute and chronic conditions, including migraine. According to a systematic review of three RCTs (n = 193) on homeopathy and migraine, results from clinical trials have been inconsistent.60 For the two trials that used individualised homeopathic prescriptions, homeopathic treatment (over a 4-month period) was found to be no more effective than placebo in reducing the frequency, intensity and severity of migraine, or the level of medication required. The remaining trial, which administered a single dose of 30c potency four times over a 2-week period, found homeopathy to be significantly superior to placebo in reducing migraine frequency, intensity and severity; it also reduced the need for medication. At first glance, these findings suggest that individualised homeopathic treatment is ineffective for migraine, yet the low quality of these trials and the poor reporting of study procedures and results do not allow for any conclusions to be made.

Massage (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Massage is the systematic manipulation of soft tissues of the body. This tactile therapy may be particularly helpful for migraine as it can help reduce anxiety and pain by stimulating parasympathetic nervous system activity, and elevate serotonin and endorphin release.61 Findings from two RCTs (n = 74) show that massage therapy (either 45 minutes a week for 6 weeks or 30 minutes twice a week for 5 weeks) elevates urinary serotonin levels and lowers salivary cortisol levels, but more importantly, significantly improves migraine frequency and sleep quality when compared with controls.62,63 Changes in migraine intensity and analgesic use were not consistent across studies. While these findings indicate massage may be of benefit to people suffering from migraine, evidence from much larger trials is still needed.

Reflexology (Level IV, Strength D, Direction +)

The stimulation of specific zones of the feet, hands and/or ears to trigger neurophysiological reflexes or responses in distant tissues, glands and organs is a guiding principle of reflexology. While evidence from a preliminary study suggests reflexology may be effective in reducing levels of perceived stress,64 and thus may have a role in the management of migraine, rigorous clinical evidence is lacking. The best available evidence regarding the use of reflexology in migraine comes from a prospective, uncontrolled exploratory study.65 Even though the study found individualised reflexology treatment for up to 6 months to be effective at reducing the incidence of headache and the level of analgesic use in 220 randomly selected patients with migraine or tension headache, the trial had major methodological limitations. The absence of a control intervention and blinding, for instance, meant the risk of bias was particularly high.

CAM prescription

Primary treatments

Secondary treatments

Referral

1. Porter R., et al, editors. The Merck manual. Rahway: Merck Research Laboratories, 2008.

2. Simon R.P., Greenberg D.A., Aminoff M.J. Clinical neurology, 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

3. Bigal M.E., Lipton R.B. The epidemiology and burden of headaches. In: Morris L., editor. Comprehensive review of headache medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

4. Goadsby P.J. Recent advances in understanding migraine mechanisms, molecules and therapeutics. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2006;13(1):39-44.

5. Schwedt T.J. Serotonin and migraine: the latest developments. Cephalalgia. 2008;27(11):1301-1307.

6. Gallai V., et al. Serum and salivary magnesium levels in migraine: Results in a group of juvenile patients. Headache. 1992;32(3):132-135.

7. Ramadan N.M., et al. Low brain magnesium in migraine. Headache. 1989;29(9):590-593.

8. Soriani S., et al. Serum and red blood cell magnesium levels in juvenile migraine patients. Headache. 1995;35(1):14-16.

9. Bianchi A., et al. Role of magnesium, coenzyme Q10, riboflavin, and vitamin B12 in migraine prophylaxis. Vitamins and Hormones. 2004;69:297-312.

10. Stargrove M.B., Treasure J., McKee D.L. Herb, nutrient and drug interactions. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

11. Kozielec T., Starobrat-Hermelin B. Assessment of magnesium levels in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Magnesium Research. 1997;10(2):143-148.

12. Pagana K.D., Pagana T.J. Mosby’s diagnostic and laboratory test reference, 9th ed. St Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2008.

13. Giles M., et al. Butterbur: an evidence-based systematic review by the natural standard research collaboration. Journal of Herbal Pharmacotherapy. 2005;5(3):119-143.

14. John P.J., et al. Effectiveness of yoga therapy in the treatment of migraine without aura: a randomized controlled trial. Headache. 2007;47(5):654-661.

15. Koseoglu E., et al. The effects of magnesium prophylaxis in migraine without aura. Magnesium Research. 2008;21(2):101-108.

16. Latha M., Kaliappan K.V. The efficacy of yoga therapy in the treatment of migraine and tension headaches. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology. 1992;13(2):95-100.

17. Peikert A., et al. Prophylaxis of migraine with oral magnesium: results from a prospective, multi-center, placebo-controlled and double-blind randomized study. Cephalalgia. 1996;16(4):257-263.

18. Guariso G., et al. Migraine and food intolerance: a controlled study in pediatric patients. Medical & Surgical Pediatrics. 1993;15(1):57-61.

19. Egger J., et al. Is migraine a food allergy? A double-blind controlled trial of oligoantigenic diet treatment. Lancet. 1983;2(8355):865-869.

20. Mansfield L.E., et al. Food allergy and adult migraine: double-blind and mediator confirmation of an allergic etiology. Annals of Allergy. 1985;55(2):126-129.

21. Littlewood J.T., et al. Red wine as a cause of migraine. Lancet. 1988;1(8585):558-559.

22. Koehler S.M., Glaros A. The effect of aspartame on migraine headache. Headache. 1988;28(1):10-14.

23. Ryan J.R.E. A clinical study of tyramine as an etiological factor in migraine. Headache. 1974;14(1):43-48.

24. Marcus D.A., et al. A double-blind provocative study of chocolate as a trigger of headache. Cephalalgia. 1997;17(8):855-862.

25. Salfield S.A., et al. Controlled study of exclusion of dietary vasoactive amines in migraine. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1987;62(5):458-460.

26. Jansen S.C., et al. Intolerance to dietary biogenic amines: a review. Annals of Allergy. Asthma and Immunology. 2003;91(3):233-240.

27. Brown J.M. Imagery coping strategies in the treatment of migraine. Pain. 1984;18(2):157-167.

28. Ilacqua G.E. Migraine headaches: coping efficacy of guided imagery training. Headache. 1994;34(2):99-102.

29. Lovell-Smith H.D. Transcendental meditation and three cases of migraine. New Zealand Medical Journal. 1985;98(780):443-445.

30. Wachholtz A.B., Pargament K.I. Migraines and meditation: does spirituality matter? Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31(4):351-366.

31. Eccleston C., et al. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. (2): CD003968

32. Osterhaus S.O., et al. Effects of behavioral psychophysiological treatment on schoolchildren with migraine in a nonclinical setting: predictors and process variables. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1993;18(6):697-715.

33. D’Souza P.J., et al. Relaxation training and written emotional disclosure for tension or migraine headaches: a randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36(1):21-32.

34. Marcus D.A., et al. Nonpharmacological treatment for migraine: incremental utility of physical therapy with relaxation and thermal biofeedback. Cephalalgia. 1998;18(5):266-272.

35. Hershey A.D., et al. Coenzyme Q10 deficiency and response to supplementation in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Headache. 2007;47(1):73-80.

36. Rozen T.D., et al. Open label trial of coenzyme Q10 as a migraine preventive. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(2):137-141.

37. Sandor P.S., et al. Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in migraine prophylaxis: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2005;64(4):713-715.

38. Taubert K. Magnesium in migraine: results of a multicenter pilot study. Fortschritte der Medizin. 1994;112(24):328-330.

39. Wang F., et al. Oral magnesium oxide prophylaxis of frequent migrainous headache in children: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache. 2003;43(6):601-610.

40. Pfaffenrath V., et al. Magnesium in the prophylaxis of migraine: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 1996;16(6):436-440.

41. Prousky J., Seely D. The treatment of migraines and tension-type headaches with intravenous and oral niacin (nicotinic acid): systematic review of the literature. Nutrition Journal. 2005;4:3.

42. Schoenen J., Jacquy J., Lenaerts M. Effectiveness of high-dose riboflavin in migraine prophylaxis: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 1998;50(2):466-470.

43. MacLennan S.C., et al. High-dose riboflavin for migraine prophylaxis in children: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Child Neurology. 2008;23(11):1300-1304.

44. Peroutka S.J. Neurogenic inflammation and migraine: implications for the therapeutics. Molecular Interventions. 2005;5(5):304-311.

45. Jho D.H., et al. Role of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in inflammation and malignancy. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2004;3(2):98-111.

46. Pradalier A., et al. Failure of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in prevention of migraine: a double-blind study versus placebo. Cephalalgia. 2001;21(8):818-822.

47. Harel Z., et al. Supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the management of recurrent migraines in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(2):154-161.

48. Oelkers-Ax R., et al. Butterbur root extract and music therapy in the prevention of childhood migraine: an explorative study. European Journal of Pain. 2008;12(3):301-313.

49. Jain N.K., Kulkarni S.K. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Tanacetum parthenium L. extract in mice and rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1991;68(1–3):251-259.

50. Kwok B.H., et al. The anti-inflammatory natural product parthenolide from the medicinal herb Feverfew directly binds to and inhibits IkappaB kinase. Chemistry and Biology. 2001;8(8):759-766.

51. Barsby R.W., et al. Feverfew extracts and parthenolide irreversibly inhibit vascular responses of the rabbit aorta. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 1992;44(9):737-740.

52. Diener H.C., et al. Efficacy and safety of 6.25 mg t.i.d. feverfew CO2-extract (MIG-99) in migraine prevention: a randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2005;25(11):1031-1041.

53. Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Feverfew for preventing migraine. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004. (1): CD002286

54. O’Brien K.A., Xue C.C. Acupuncture. In: Robson T., editor. An introduction to complementary medicine. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

55. Linde K., et al. Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. (1): CD001218

56. Bronfort G., et al. Efficacy of spinal manipulation for chronic headache: a systematic review. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2001;24(7):457-466.

57. Tuchin P.J., Pollard H., Bonello R. A randomized controlled trial of chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy for migraine. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2000;23(2):91-95.

58. Nelson C.F., et al. The efficacy of spinal manipulation, amitriptyline and the combination of both therapies for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 1998;21(8):511-519.

59. Parker G.B., Tupling H., Pryor D.S. A controlled trial of cervical manipulation of migraine. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Medicine. 1978;8(6):589-593.

60. Owen J.M., Green B.N. Homeopathic treatment of headaches: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 2004;3(2):45-52.

61. Moyer C.A., Rounds J., Hannum J.W. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(1):3-18.

62. Hernandez-reif M., et al. Migraine headaches are reduced by massage therapy. International Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;96(1–2):1-11.

63. Lawler S.P., Cameron L.D. A randomized, controlled trial of massage therapy as a treatment for migraine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;32(1):50-59.

64. Lee Y.M. Effect of self-foot reflexology massage on depression, stress responses and immune functions of middle aged women. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2006;36(1):179-188.

65. Launso L., Brendstrup E., Arnberg S. An exploratory study of reflexological treatment for headache. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 1999;5(3):57-65.