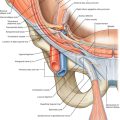

CHAPTER 8

Cervicogenic Vertigo

Definition

Cervicogenic vertigo is the false sense of motion that is due to cervical musculoskeletal dysfunction. The symptoms may be secondary to post-traumatic events with resultant whiplash or postconcussive syndrome. Alternatively, cervicogenic vertigo may be part of a more generalized disorder, such as fibromyalgia or underlying cervical osteoarthritis.

Cervicogenic vertigo is thought to result from convergence of the cervical and cranial nerve inputs and their close approximation in the upper cervical spinal segments of the spinal cord [1,2]. Dizziness and vertigo, common presenting symptoms, account for 8 million primary care visits to physicians in the United States each year and represent the most common presenting complaint in patients older than 75 years [3]. In fact, 40% to 80% of patients with neck trauma experience vertigo, particularly after whiplash injury. The incidence of symptoms of dizziness and vertigo in whiplash patients has been reported as 20% to 58% [4,5].

Symptoms

Patients with cervicogenic vertigo experience a false sense of motion, often whirling or spinning. Some patients experience sensations of floating, bobbing, tilting, or drifting. Others experience nausea, visual motor sensitivity, and ear fullness [6]. The symptoms are often provoked or triggered by neck movement or sustained awkward head positioning [7–9]. Cervical pain or headache may interfere with sleep and functional activities. At times, patients with coexistent cervical radiculitis may complain of paresthesias in the upper cervical dermatomes.

Physical Examination

The essential elements of the physical examination are normal neurologic, ear, and eye examination findings for nystagmus. Abnormalities in any of these aspects of the examination indicate a need to exclude other otologic or neurologic conditions, such as Meniere disease, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, and stroke [5,10]. A careful cervical examination should be performed, including range of motion testing and palpation of the facet joints to assess mechanical dysfunction. Myofascial trigger points should be sought in the sternocleidomastoid, cervical paraspinal, levator scapulae, upper trapezius, and suboccipital musculature. Patients with cervicogenic headache and disequilibrium have a significantly higher incidence of restricted cervical flexion or extension and painful cervical joint dysfunction and muscle tightness [11,12]. Palpation in these areas can often reproduce the symptoms experienced as cervicogenic vertigo [13].

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations may include difficulty with walking, balance, or equilibrium. As a result, patients may not feel confident with activities such as driving because cervical rotation may induce symptoms. Occupations that require balance and coordination (such as construction) are often limited. Anxiety about the occurrence of disequilibrium may contribute to secondary disability.

Diagnostic Studies

Cervicogenic dizziness is a clinical diagnosis. Testing may include cervical radiographs to rule out cervical osteoarthritis or instability. Cervical magnetic resonance imaging is indicated when cervical spondylosis is suspected, either as a cause of the condition or as an associated diagnosis. Brain magnetic resonance imaging or magnetic resonance angiography may be ordered to exclude vascular lesions or tumor (i.e., acoustic neuroma). A comprehensive neurotologic test battery and consultation are preferred if a primary otologic disorder or post-traumatic vertigo is considered [14].

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment involves reassurance and education of the patient. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are useful to help pain control for those who have underlying cervical osteoarthritis. Muscle relaxants such as cyclobenzaprine, carisoprodol, and low-dose tricyclic antidepressants may be used at bedtime to facilitate sleep and muscle relaxation for myofascial pain. We occasionally prescribe ondansetron (4 to 8 mg every 8 hours as needed) if disequilibrium is accompanied by significant nausea.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is aimed at reducing muscle spasm, increasing cervical range of motion, improving posture, and restoring function. A physical therapist with training and experience in manual therapy, myofascial and trigger point treatment, and neck and trunk stabilization techniques should evaluate and treat the patient to restore normal cervical function [15]. The use of gentle manual therapy is validated by moderate evidence, with sustained natural apophyseal glides being particularly beneficial in relief of dizziness and pain up to at least 12 weeks [16,17]. Occupational therapy can improve posture, ergonomics, and functional daily activities [18]. Vestibular rehabilitation therapy helps patients develop compensatory responses and normalizes cervical sensory input [16].

Ergonomic accessories, such as telephone earset or headset, may help the patient avoid awkward head and neck postures that contribute to symptoms. Psychological or behavioral medicine consultation and treatment can aid the patient in overcoming the fear, avoidance, and anxiety that often develop [16,19].

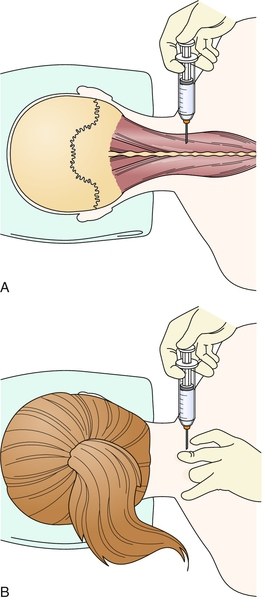

Procedures

Trigger point injections with local anesthetic (1% lidocaine or 0.25% bupivacaine) are often helpful to decrease cervical muscle pain (Fig. 8.1). The clinician should locate those trigger point areas that reproduce the patient’s symptoms. Acupuncture with an emphasis on local treatment of muscle spasm may be an alternative to trigger point injection [20,21].

Although botulinum toxin injection may have a role in the treatment of cervicogenic headache [22,23], there are no data yet on the treatment of cervicogenic vertigo with botulinum toxin.

Surgery

There is no surgery indicated for treatment of this disorder, unless there is coexistent neurologically significant cervical stenosis or disc herniation.

Potential Disease Complications

The major complications are inactivity, deconditioning, falls, fear of going outside the home, anxiety, and depression. Chronic intractable neck pain and persistent dizziness may persist in spite of treatment.

Potential Treatment Complications

Side effects from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may include gastric, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, and hematologic complications [24]. Muscle relaxants and tricyclics may induce fatigue, somnolence, constipation, urinary retention, and other anticholinergic side effects. Local injections may result in local pain, ecchymosis, intravascular injection, or pneumothorax if they are improperly executed.