CHAPTER 8 Airway Management

1 List several indications for endotracheal intubation

Surgical procedures in which the anesthesiologist cannot easily control the airway (e.g., prone, sitting, or lateral decubitus procedures)

Surgical procedures in which the anesthesiologist cannot easily control the airway (e.g., prone, sitting, or lateral decubitus procedures)5 Review the Mallampati classification

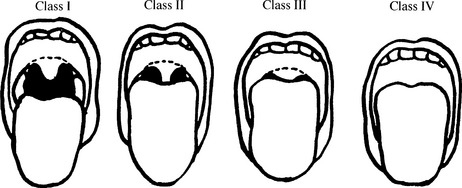

Mallampati has organized patients into classes I to IV based on the visualized structures (Figure 8-1). Visualization of fewer anatomic structures (particularly classes III and IV) is associated with difficult laryngeal exposure. With the patient sitting upright, mouth fully open, and tongue protruding, classification is based on visualization of the following structures:

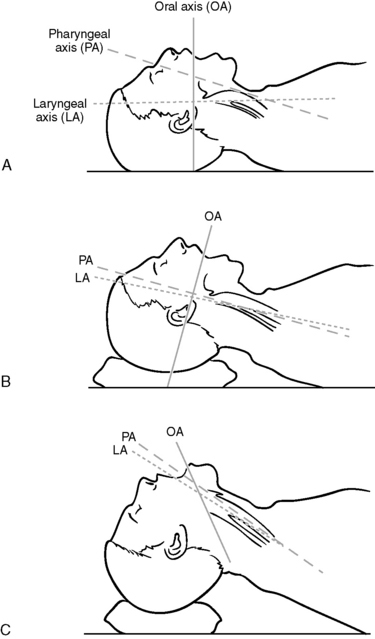

13 What structures must be aligned to accomplish visualization of the larynx?

To directly visualize the larynx it is necessary to align the oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal axes. To facilitate this process, elevating the head on a small pillow and extending the head at the atlanto-occipal axes are necessary (Figure 8-2).

14 What is a GlideScope?

20 How is awake intubation performed?

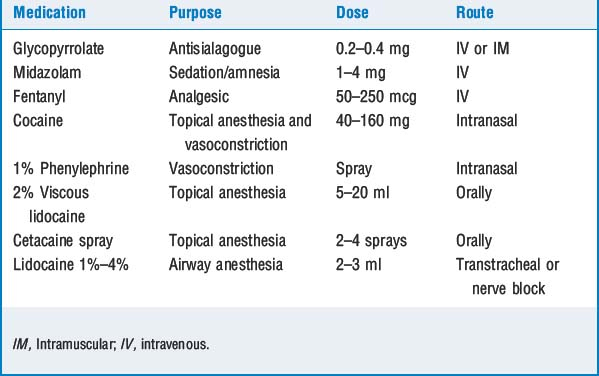

In preparing the patient, administration of glycopyrrolate, 0.2 to 0.4 mg 30 minutes before the procedure, is useful to reduce secretions. Many clinicians also administer nebulized lidocaine to provide topical anesthesia of the entire airway, although many techniques are available to provide airway anesthesia. Once the patient arrives in the operating suite, standard anesthetic monitors are applied, and supplemental oxygen is administered. The patient is sedated with appropriate agents (e.g., opioid, benzodiazepine, propofol). The level of sedation is titrated so the patient is not rendered obtunded, apneic, or unable to protect the airway (Table 8-1).

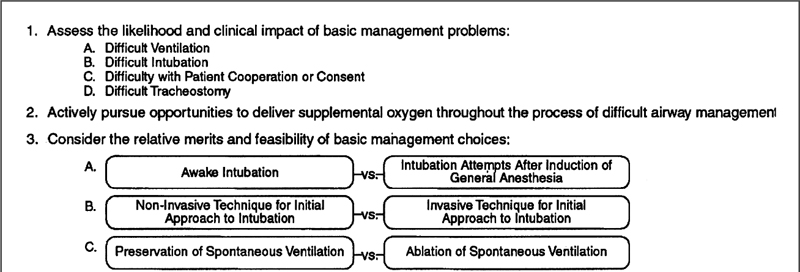

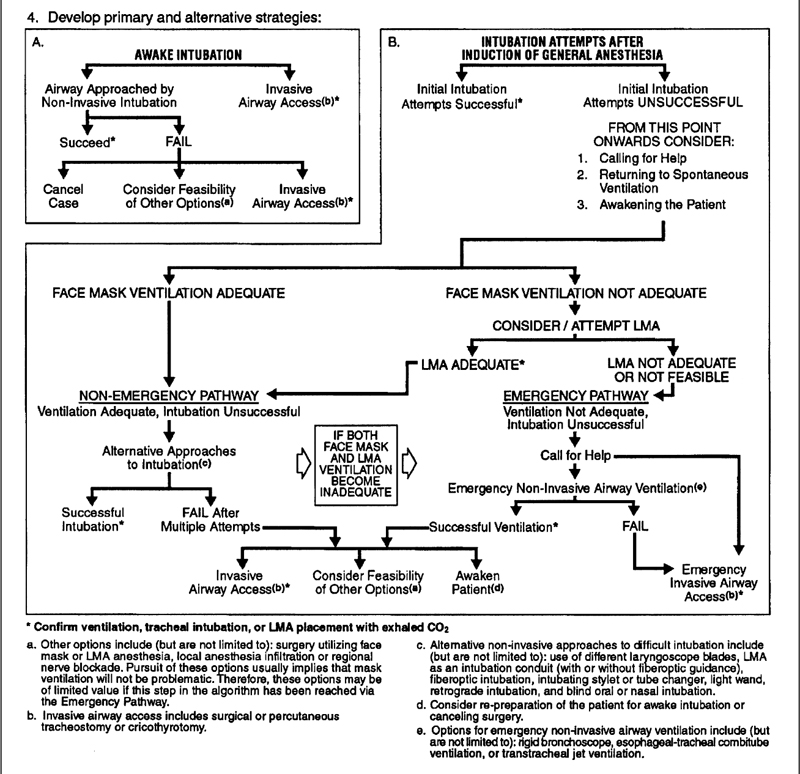

23 The patient has been anesthetized and paralyzed, but the airway is difficult to intubate. Is there an organized approach to handling this problem?

The patient who is difficult to ventilate and intubate is quite possibly the most serious problem faced by anesthesiologists because hypoxic brain injuries and cardiac arrest are real possibilities in this scenario. It has been established that persistent failed intubation attempts are associated with death. Although a thorough history and physical examination are likely to identify the majority of patients with difficult airways, unanticipated problems occasionally present. Only through preplanning and practiced algorithms are such situations managed optimally. The American Society of Anesthesiologists has prepared a difficult airway algorithm (Figure 8-3) to assist the clinician. The relative merits of different management options (surgical vs. nonsurgical airway, awake vs. postinduction intubation, spontaneous vs. assisted ventilation) are weighed. Once these decisions have been made, primary and alternative strategies are laid out to assist in stepwise management. This algorithm deserves close and repeated inspection before the anesthesiologist attempts to manage such problems. This is no time for heroism; if intubation or ventilation is difficult, call for help.

25 What are criteria for extubation?

The patient should be awake and responsive with stable vital signs. Adequate reversal of neuromuscular blockade must be established as demonstrated by sustained head lift. In equivocal situations negative inspiratory force should exceed 20 mm Hg (see Question 2).

29 Anesthesiologists routinely deliver 100% oxygen for a few minutes before extubation. What is the logic behind this action and why might an FiO2 of 80% be better?

1. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the ASA Task Force on management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269-1277.

2. Kheterpal S., Han R., Tremper K.K., et al. Incidence and predictors of difficult and impossible mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:885-891.

3. Peterson G.M., et al. Management of the difficult airway: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:33-39.