CHAPTER 77 Acute Pain Management

3 How is pain assessed?

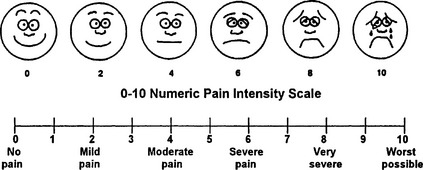

The magnitude of pain and the response to treatment can be monitored in several ways. A visual analog scale may be used in which the patient chooses a mark on a 10-cm line corresponding with the perceived amount of pain being experienced. Scales using color (from blue for minimal pain through violet hues to bright red for maximal pain) or numbers (from zero for no pain through ten for maximal pain) have been devised for adults (Figure 77-1). A scale of 10 faces, ranging from very happy to very sad, can be used in young children. The child points to the face matching the way he or she feels. Verbal descriptive scales such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire are useful both for clinical and research purposes. Functional ability is also a useful measure of pain. In some patients, especially those who also have chronic pain, assessing ability to perform regular functions such as activities of daily living, performing at work, or ability to participate in leisure activities may be more useful than collecting pain scores. In a hospital setting the number of times a patient spontaneously leaves the room may provide a more accurate assessment than pain scores. Pain scores with activity may be a more sensitive measure of analgesia because it is easier to control pain at rest. The pain scale can be used to ensure that an intervention such as an increased dose of opioids is effective in decreasing the patient’s pain.

4 What medications are useful in treating acute pain?

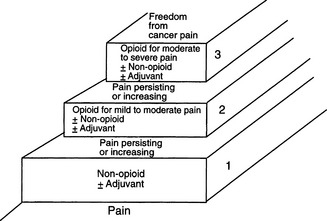

The medications useful in treating acute pain are similar to those used in treating other types of pain. The World Health Organization analgesic ladder developed for treating patients with cancer pain also provides a useful approach to treating acute pain (Figure 77-2). At the lowest level (mild pain), nonopioid analgesics such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g., ibuprofen or acetaminophen) are useful. Such drugs have an analgesic ceiling; above a certain dose no further analgesia is expected. For moderate pain compounds combining acetaminophen or aspirin with an opioid are useful. The inclusion of acetaminophen limits the amount of such agents that should be used within a 24-hour period because toxic accumulations can occur. The next step to consider would be adding an agent such as tramadol. Tramadol has a dual mechanism of action as a weak μ-opioid agonist and a weak inhibitor of reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin. Care should be taken when concurrently prescribing with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors since there is a potential increased incidence of serotonin syndrome (although there are very few reported cases). With severe levels of pain an opioid such as morphine or hydromorphone is a better choice; such opioids have no analgesic ceiling. Most postoperative or trauma patients initially respond better to morphine or other opioids. Intravenous agents are usually faster, and patients report more satisfaction with analgesia after surgery or trauma. By the time the patient is eating and ready for discharge, opioid-acetaminophen agents or NSAIDs are often adequate.

12 How do agonist-antagonists differ from opioids such as morphine?

13 How should patients with continuous infusions for analgesia or patient-controlled analgesia pumps be monitored?

14 How is an oral agent chosen for a patient who previously received intravenous opioids?

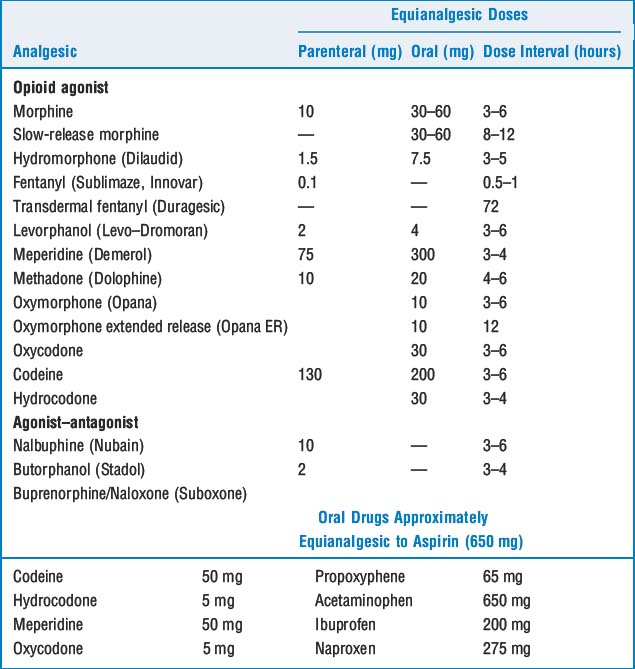

Choice of an oral agent should be based on how much pain the patient still has and how much opioid was needed to control the pain. Opioid-acetaminophen compounds are adequate for patients whose pain requires 0 to 2 mg/hr of morphine. Hydrocodone-acetaminophen is a milder analgesic than oxycodone-acetaminophen and is useful for patients who require minimal opioids. An equal analgesic dosing chart (Table 77-1) can be used to select equivalent levels of analgesics.

1. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1573-1581.

2. Rathwell J.P., Neal J.M., Viscomi C.M. Regional anesthesia. St Louis: Mosby, 2004.

3. Sindrup S.H., Troels S.J. Efficacy of pharmacological treatments of neuropathic pain: an update and effect related to mechanism of drug action. Pain. 1999;83:389-400.