CHAPTER 76

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Sprain

Farshad Adib, MD; Christine Curtis, MD; Peter Bienkowski, MD; Lyle J. Micheli, MD

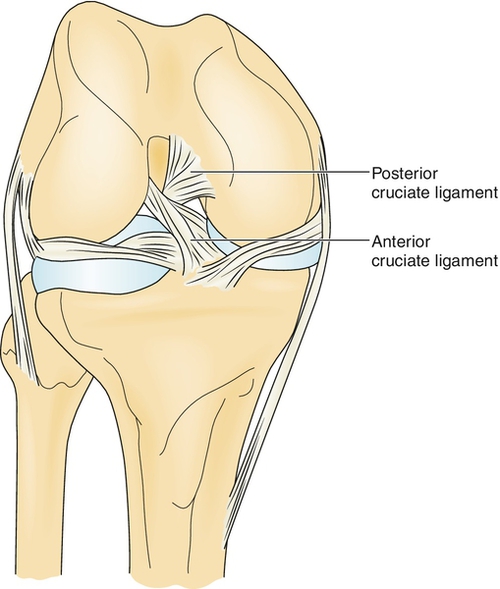

Definition

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) tears represent 5% to 38% of all knee ligament injuries [1,2]. The PCL is an intra-articular but extrasynovial structure that arises from the posterior aspect of the tibial plateau (about 1 cm distal to the joint line), crosses (“cruciate”) behind the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), and inserts into the lateral portion of the medial femoral condyle (Fig. 76.1). The main function of the PCL is to resist posterior displacement of the tibia on the femur. It also acts as a secondary restraint to external tibial rotation. The PCL also has some restraint against varus and valgus forces. The larger and stronger anterolateral bundle is tight in flexion, whereas the posteromedial bundle is tight in extension. The anterior meniscofemoral ligament (Humphry) and posterior meniscofemoral ligament (Wrisberg) make a Y-shaped sling around the PCL [3]. The average distance between the center of the femoral attachments of anterolateral and posteromedial bundles is 12.1 ± 1.3 mm; this distance on the tibial side is 8.9 ± 1.2 mm [4].

Together with the ACL, the PCL functions in the “screw-home” mechanism of the knee by which the tibia glides to its exact position at terminal knee extension. In general, PCL tears occur in a flexed knee when the tibia is displaced posteriorly. This can occur in a motor vehicle accident (dashboard injury) or during a fall on a flexed knee with the foot in plantar flexion. The PCL may also rupture from hyperextension and rotation on a planted foot or on forced hyperflexion. PCL injuries may occur in isolation, but they generally occur with other injuries (e.g., ACL tear, collateral ligament tear, and meniscal injuries).

In a chronic PCL-deficient knee, an increase of force on the medial and patellofemoral compartments might lead to development of early degenerative arthritis [5]. In contrast to ACL injuries, most series of PCL injuries have reported a higher incidence of injury to men [6]. Fewer studies have been done about PCL injuries in comparison to ACL injuries.

Symptoms

It is important to obtain information about the nature of the injury. Typically, patients report that they have fallen on a flexed knee or have sustained a blow to the anterior knee when it was flexed (e.g., on the dashboard of a car). Rarely, patients may recall feeling or hearing a “pop” at the time of injury (more common in ACL tear). Patients may have pain in the posterior aspect of the knee in the acute cases or along the medial or patellofemoral region in the chronic cases.

Patients may report instability, stiffness, and an inability to bear weight and to walk. Swelling can range from insignificant to very swollen.

Physical Examination

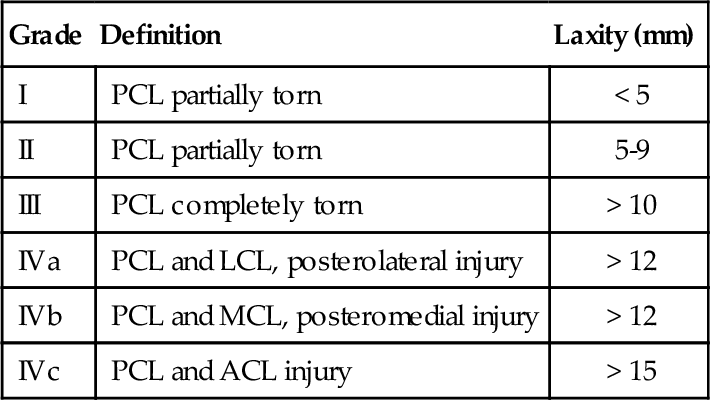

In an acute injury, there may be contusion of the anterior tibia, and popliteal ecchymosis may be present. Swelling and effusion will vary and may not be present at all. Limb alignment, gait pattern, and range of motion should be evaluated. See Table 76.1 for the general classifications of PCL injuries. It has been shown that a grade III on posterior drawer testing and posterior tibial translation on stress radiography of more than 10 mm correlate with the presence of a posterolateral corner injury in addition to a complete disruption of the PCL [7].

It is essential during the examination of the knee to evaluate all knee ligaments thoroughly to identify combined ligamentous injuries. The goal of PCL evaluation is to identify posterior subluxation of the tibia, which occurs with PCL insufficiency.

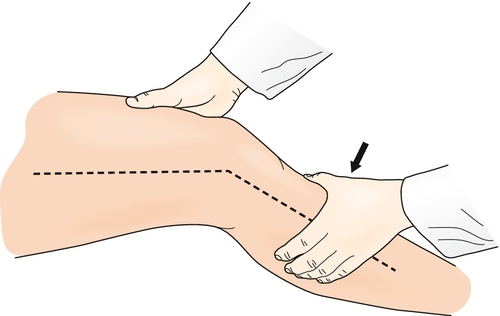

The “gold standard” of PCL examination is the posterior drawer test (Fig. 76.2). During this test, the knee is flexed at 90 degrees with the hip held at 45 degrees of flexion. It is essential to appreciate a normal 1-cm step-off of the medial tibial plateau anterior to the medial femoral condyle. The absence of the step-off should alert the clinician to a possibility of PCL injury. Posterior pressure is applied to the tibia while the amount of displacement of the medial tibial step-off and the quality of the endpoint in comparison with the contralateral knee are noted. Posterolateral instability may be evaluated by the posterior drawer test with the foot externally rotated 15 degrees. Similarly, posteromedial instability is assessed by the posterior drawer test with the foot internally rotated 15 degrees.

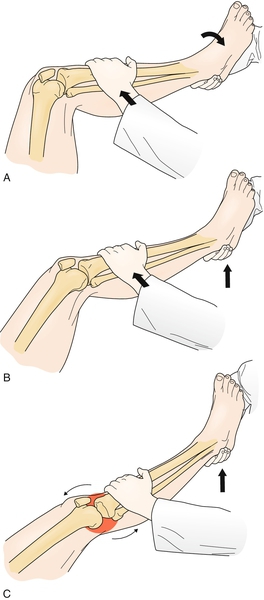

The posterior Lachman test involves positioning of the knee at 30 degrees of flexion with posterior pressure applied to the proximal tibia (Fig. 76.3). The extent of displacement and the quality of the endpoint are evaluated and compared with the contralateral knee.

The posterior sag test is performed with the patient supine with the hips and knees at 90 degrees of flexion (Fig. 76.4). The clinician grasps both heels and inspects for posterior tibial translation consistent with an insufficient PCL.

The reverse pivot shift includes a valgus-loaded, externally rotated knee moved from 90 degrees of flexion to full extension (Fig. 76.5). A positive test result is indicated by a pivot shift felt at 20 to 30 degrees when the posteriorly subluxated tibia is reduced.

The dynamic posterior shift test is implemented by extending the knee from 90 degrees of flexion to full extension with 90 degrees of hip flexion. A positive result is indicated if the tibia is reduced with a “clunk” near full extension.

The quadriceps active test is achieved with the knee flexed at 60 degrees while the foot is secured by the clinician. The patient attempts to extend the knee statically. PCL insufficiency is demonstrated by anterior tibial translation from a subluxated position.

A careful neurovascular examination should be performed to rule out any injury to the popliteal artery and tibial and peroneal nerves. Some weakness of muscle may be detected because of pain or inactivity. Physical examination under anesthesia is a critical step before reconstruction.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations of PCL tears may include difficulty with walking and a decrease in the level of functioning because of pain as well as apprehension of instability. Athletes may be unable to complete cutting movements. However, PCL injury is often less debilitating than ACL injury, and many athletes are still able to participate effectively in running sports. Return to sport after treatment of PCL injury is common, but in the majority of cases, development of degenerative changes is inevitable [8].

Diagnostic Studies

Diagnostic testing is useful as an adjunct to the clinical examination. The KT-1000 arthrometer is highly specific in the detection of high-grade (grade II, grade III) PCL tears [9]. Stress radiographs may document the extent of posterior instability but are rarely obtained in settings where magnetic resonance imaging is readily available. After an acute injury, plain radiographs must be performed to rule out fractures, including PCL avulsions (the tunnel view is best to visualize this). Magnetic resonance imaging assessment is highly specific and sensitive in assessment of PCL injuries, particularly when newer fat suppression and “fast spin” techniques are used [10–12]. Finally, diagnostic arthroscopy allows direct visualization of the PCL.

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment consists of protection, rest, ice, compression, and elevation (PRICE), crutches, an extension brace, and short-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Analgesics may be used to control pain if this is an issue. Currently, nonoperative treatment is advocated for those with isolated PCL injuries with mild (grade I or grade II) laxity [9]. Some recommend conservative treatment for acute, isolated PCL injury as well as for chronic, isolated, asymptomatic PCL injury when it is newly diagnosed with no history of prior rehabilitation [13]. Subjective scores of patients with acute, isolated PCL injuries were independent of grade of PCL laxity, and mean scores did not decrease with time from injury [14].

Rehabilitation

Nonoperative rehabilitation begins after the signs and symptoms of acute injury have subsided (7 to 10 days). Range of motion and progressive resistance exercise for the quadriceps is initiated while posterior tibial sag is prevented. The use of a PCL functional brace has not been proved to be effective, although some patients may find it useful [15]. After acute symptoms have subsided, or immediately in dealing with a chronic tear, daily stationary bicycle exercises can be initiated. After 3 months, closed chain exercises are started, with the exception of isolated hamstring strengthening, which is done later in the course [16].

Postoperative PCL rehabilitation includes initial bracing in full extension to prevent posterior tibial translation. Continuous passive motion, straight-leg raising, and quadriceps static exercises are initiated immediately after surgery. The day after surgery, partial weight bearing with crutches is initiated as tolerated. In the early phase of rehabilitation, gravity-assisted flexion exercises to 90 degrees and closed chain exercises emphasizing quadriceps muscle strengthening are pursued. The progression to more than 90 degrees of flexion is delayed until 6 weeks after surgery. Rehabilitation after PCL reconstruction is more conservative than after ACL reconstruction.

Two studies by Italian investigators have documented the frequent clinical observation that the PCL, in contrast to the ACL, can undergo in situ healing of partial lesions, with improved stability and function [17–19]. This has been attributed to the capsular contiguity of the ligament, with better opportunity for revascularization than in the ACL [1]. It is thus imperative that the ligament be protected from undue stress during the rehabilitative phase of treatment. Intact meniscofemoral ligaments may support the injured PCL during the healing phase. This scaffold effect of meniscofemoral ligaments could be another reason for the healing potential of PCL injuries. At 9 to 12 months after surgical intervention, the patient with full range of motion, equal strength compared with the contralateral leg, and a stable knee is allowed to return to full activity.

Procedures

Arthrocentesis is performed for painful effusions (hemarthrosis). As mentioned earlier, KT-1000 arthrometer testing is done for diagnostic purposes and to document the degree of instability [9].

Surgery

Surgical intervention is advocated for patients with bone avulsion fractures, combined ligament injuries, and chronic symptomatic PCL laxity, particularly if this interferes with athletic participation in elite athletes [15]. In a high percentage of cases, athletic participation is still possible with PCL insufficiency [6]. Management includes immobilization in extension with a Velcro knee immobilizer and avoidance of hamstring exercise. It is important to keep in mind that grade III PCL injury almost always is associated with the posterolateral corner injury, which must be addressed at the time of PCL reconstruction to obtain a good clinical result.

Bone avulsions are best treated with anatomic repair, either by open technique with screws or by an arthroscopic method with anchor sutures [20]. Various surgical techniques have been developed for the reconstruction of the PCL. Controversy exists as to the most effective procedure [16]. The aim of surgery is to replace the PCL with a graft inserted into a tunnel drilled through the tibia and femur. Allograft or autograft tissue is most commonly used. Donor sites include the patellar tendon, the hamstring tendons, and, rarely, the quadriceps tendon [21]. Achilles tendon allograft is also useful. A mixed graft consisting of a hamstring (semitendinosus and gracilis) autograft plus tibialis anterior allograft tendon has been used with good results [22]. PCL reconstruction with artificial ligament is an alternative treatment option [23]. PCL reconstruction is performed arthroscopically, arthroscopically assisted, or open [13]. In the presence of significant bone malalignment, it should be addressed simultaneously or as the first step before the reconstruction. Proximal tibial slope should be considered in treating combined PCL and posterolateral corner injuries of the knee. It has been shown that increasing posterior tibial slope may improve sagittal stability in the PCL- and posterolateral corner–deficient knee [24].

Potential Disease Complications

Potential disease complications include pain, limitation of function and activity, and onset of degenerative arthritis. Patients with isolated PCL tears tend to fare better than do patients with combined ligamentous injuries [25]. Studies suggest that nonoperatively treated PCL injuries allow many athletes to return to their sport independent of level of laxity [25]. However, late degenerative arthritis has been reported as a consequence of PCL instability [26].

Potential Treatment Complications

Treatment complications include the well-known side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Prolonged bracing or immobilization can lead to significant muscle weakness and atrophy. The risks of surgery, although uncommon, are also well known. These include the risks of anesthesia. In addition, bleeding is controlled with a tourniquet and surgical hemostasis. Infection is limited with diligent sterile technique as well as with antibiotics. Damage to nerve and vascular structures, the popliteal vessels in particular, is a slight risk. Postoperative laxity of the PCL graft may occur. The theoretical risk of disease transmission with the use of allograft tissues is extremely low.