CHAPTER 75

Peroneal Neuropathy

Definition

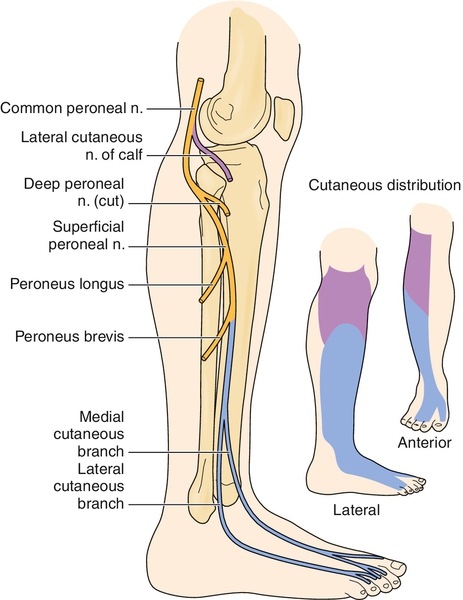

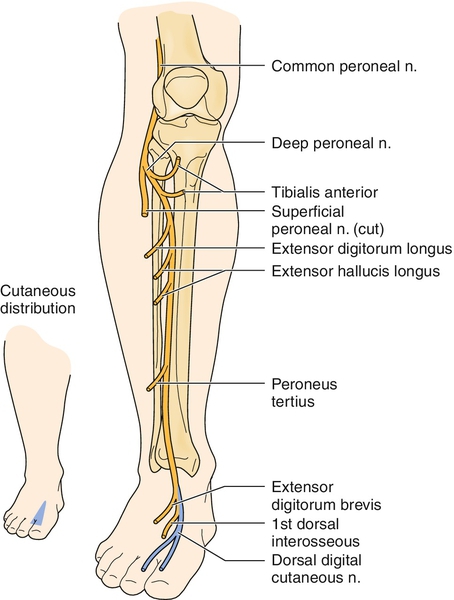

Peroneal neuropathy, the most common entrapment neuropathy of the lower extremity [1], is compromise of any portion of the peroneal nerve. This can be from its origins within the sciatic nerve, in which it remains distinct from the tibial portion, throughout the course of the sciatic nerve, to its terminations in the leg and foot. The common peroneal nerve completely separates from the tibial nerve in the upper popliteal fossa and then traverses laterally to curve superficially around the fibular head. Before the fibular head, the lateral cutaneous nerve of the calf branches off to supply cutaneous sensation to the upper lateral leg. Near the fibular head, the common peroneal nerve bifurcates into the superficial peroneal nerve and deep peroneal nerve, which describes their relative locations as they wrap around the fibular head. Because the deep portion is immediately adjacent to the hard bony surface, it is more susceptible to compression injuries at the fibular head, which is the most common site of peroneal nerve compromise [2,3].

The common peroneal nerve provides the lateral cutaneous nerve of the calf and the motor branch to the short head of the biceps femoris above the fibular head. The superficial peroneal nerve is predominantly sensory, providing cutaneous sensation to the lateral lower leg and most of the foot dorsum. The superficial peroneal nerve also innervates the foot evertors, peroneus longus and brevis. The deep peroneal nerve is predominantly motor, innervating the foot and toe dorsiflexors, but it has a small cutaneous representation at the dorsal first web space of the foot.

Predisposing factors for peroneal mononeuropathy at the fibular head, the most common site of compromise, include weight loss [2,4–7], diabetes [2,8], peripheral polyneuropathy [2], and positioning and localized prolonged pressure [9], such as habitual leg crossing [1] or prolonged squatting [2,10]. A history of such sustained pressure should be elicited.

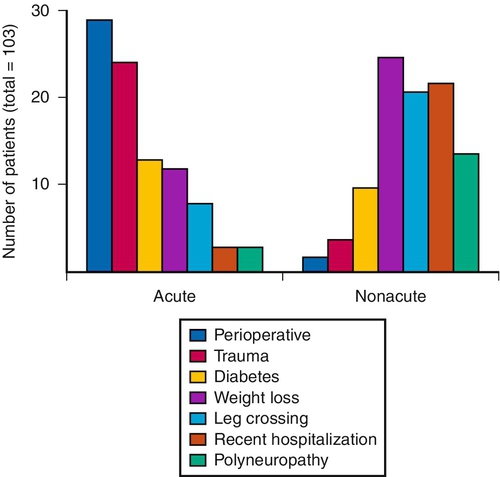

Figure 75.1 shows the most common causes of acute and nonacute lesions. Iatrogenic causes should be considered. These include anesthesia for surgery, leading to immobility and possible positioning issues [9,11,12]; surgery about the hip [13–15], knee [16], or ankle [17]; prolonged imposed bed rest with decreased sensorium due to sepsis or coma [2,18]; intermittent sequential pneumatic compression [19]; acupuncture [20]; and plaster casts [2], braces, sports icing and compression wraps [21], and, ironically, ankle-foot orthoses [5,22]. A history of severe inversion ankle sprain or blunt trauma to the ankle, leg, or fibular head can be helpful in identifying likely pathophysiologic mechanisms.

Stretch injury commonly occurs at the hip region and may be associated with hip surgery (e.g., total hip arthroplasty, especially if the limb is lengthened) [13] or traumatic hip dislocation. The peroneal portion of the sciatic nerve is more susceptible to stretch injuries than the tibial portion because of its lateral position and the shorter distance between the piriformis and the fibular head than between the piriformis and the tarsal tunnel (e.g., the sites of relative fixation of these two nerves). Distal peroneal nerve stretch injury can also occur at the point where it passes through the peroneus longus muscle. In addition, peroneal nerve injury is proposed to occur after stroke by equinovarus footdrop posturing [23].

Symptoms

Peroneal neuropathy typically is manifested with acute footdrop, but this can sometimes occur insidiously during several days to weeks. The footdrop can be complete or partial, often with increased tripping or falls as the primary complaint. Numbness or dysesthesias frequently occur in the lower lateral leg and dorsum of the foot, although pain is uncommon. When pain is present, it is usually located around the knee and felt as deep and ill-defined [2]. When pain is prominent and neuropathic in character, stretch injury of the peroneal portion of the sciatic nerve should be considered.

Physical Examination

The examination should be guided by a close understanding of the relevant anatomy, with focused study of the elements of each component of the peroneal nerve.

Sensory deficits in the upper lateral leg (Fig. 75.2) suggest a lesion proximal to the fibular head. Testing of foot inversion, to rule out concomitant tibial nerve compromise and therefore sciatic nerve as the likely site of injury, must be performed with the foot passively slightly dorsiflexed for optimal strength testing (often the foot will initially, at rest, be in a plantar flexed position during examination as a result of the existing footdrop) because inversion is normally weak when the foot is relatively plantar flexed [1]. With the long head of the biceps femoris intact, knee flexion strength will test normal despite a compromise to the short head of the biceps femoris strength. Palpation may reveal a lack of tissue tensing where the short head of the biceps femoris should be located. This is, however, challenging to discern and helpful only in the case of acute complete proximal peroneal nerve compromise with relative sparing of the tibial-innervated hamstring muscles. The function and innervation of the long and short heads of the biceps femoris can be more accurately determined electrodiagnostically. If both are compromised, knee flexion will be weak, as will plantar flexion and toe flexion, suggesting a sciatic nerve lesion. Hip abduction strength testing has been found helpful in distinguishing peroneal neuropathy from L5 radiculopathy in patients with footdrop [24]. Muscle stretch reflexes will usually be normal unless the sciatic nerve is severely compromised, when the medial hamstring and Achilles reflexes could be reduced or absent.

Sensory deficit or dysesthesia in the lower lateral leg and over most of the dorsum of the foot suggests involvement of the superficial peroneal or this portion of the sciatic nerve (see Fig. 75.2). Eversion weakness is consistent with superficial peroneal nerve compromise. If the superficial peroneal nerve lesion is isolated, then Achilles, quadriceps, and medial hamstring muscle stretch reflexes will be normal.

If eversion is strong but dorsiflexion is very weak, a more focal deep peroneal nerve compromise is suggested. There may be sensory deficits or dysesthesias along the isolated area of the dorsum of the first web space of the foot on the affected side (Fig. 75.3). A combination of deep and superficial peroneal nerve branch compromise often occurs, usually affecting the deep branch more severely than the superficial branch, especially with lesions at the fibular head.

Functional Limitations

The most common limitation is due to footdrop. This can lead to frequent tripping or falls and altered gait with foot slapping, circumduction, or hip hiking. These gait compensations require more energy per distance for walking and place one at a greater fall risk than if they are corrected by an ankle-foot orthosis. Any task requiring dynamic foot eversion or dorsiflexion muscle activity, such as walking and running or balance activities such as occur during lower extremity dressing, bathing, sports activities, or driving (especially when the right side is affected) [25], can be impaired.

Diagnostic Studies

Electrophysiologic studies are the “gold standard” for diagnosis of suspected peroneal neuropathy [1,26–29]. These studies can help distinguish site and severity of compromise from other possible causes of footdrop (see the section on differential diagnosis) [1,2,26]. This includes both sensory nerve conduction studies of the superficial peroneal nerve and motor nerve conduction studies of the common, deep, and superficial peroneal nerve to the functionally deficient muscles, such as the tibialis anterior or peroneus longus. Although the peroneal motor nerve is commonly studied to the extensor digitorum brevis for polyneuropathy screening, this is not the targeted muscle to evaluate footdrop, or dorsiflexion weakness, as the tibialis anterior is the more relevant and germane motor conduction study [2,26]. Needle electromyography, especially of the short head of the biceps femoris, can help determine if the lesion is proximal to the fibular head. Additional prognostic and severity data can be obtained by needle study as well as by comparison nerve conduction studies between the involved and uninvolved sides.

If the etiology cannot be determined with reasonable certainty, imaging studies can help identify less common, nontraumatic causes of peroneal neuropathy. These include ganglia [30], nerve tumors (primary nerve sheath, benign or malignant, or metastatic tumors with invasion or compression) [29], hematomas (especially with anticoagulation or bleeding dyscrasias) [2], aneurysms [31], venous thromboses [32,33], and knee osteoarthritis [34,35]. The most common imaging study is magnetic resonance imaging along the course of the nerve [13,36–38], but imaging studies could include plain radiography or ultrasonography, which is becoming more widely available and used [30,39–42].

Treatment

Initial

Treatment depends on lesion site and prognostic factors found on electrophysiologic studies. If a good prognosis is predicted, watchful waiting is indicated with temporary adaptations and preventive measures to minimize functional impact until complete recovery occurs. Removal of pressure to the involved area is important, and this may require bed rail modifications or protective padding around the knees, especially for sleep. Work or sports activities and clothing that could result in pressure to the involved areas should be assessed and modified to eliminate any unnecessary pressure or padding added to minimize blunt trauma effects. Habitual leg crossers must modify this behavior. With pressure relief, neurapraxic injuries often significantly improve by 6 weeks. If the lesion is more axon stretch, recovery can take much longer, as much as a day for each millimeter that the axon must regrow. Completely denervated muscles need reinnervation by 18 months for recovery; the higher the lesion, the more likely a poor outcome will result for distal muscles. If prognosis is poor, such as with a severe high sciatic nerve injury, longer term adaptations and home preventive programs should be planned, as well as possible surgical considerations, especially in children [43].

If pain is neuropathic in nature (burning, tingling, or associated with hyperpathia), neuropathic pain medications such as the anticonvulsants or tricyclic antidepressants should be considered. These must be started in low dosage, taken routinely, and slowly titrated up; a steady-state level is needed to help block the new aberrant sodium channels of injured nerves, which is one mechanism by which these medications decrease neuropathic pain. These medications are not used on an as-needed basis like other more typical analgesics. When they are effective, the neuropathic pain medications tend to continue to be effective chronically and are often needed 6 months to 2 years, if not indefinitely [44].

Rehabilitation

Adaptive devices include an ankle-foot orthosis, which can be a simple, fixed-ankle, off-the-shelf model if no other comorbidities exist. This brace helps with footdrop and improves foot clearance during the leg swing-through phase of gait. If the peroneal neuropathy occurs in isolation, then no plantar sensory loss is present, and concerns for contact pressure of skin to orthosis are lessened. If the patient presents with comorbid tibial nerve deficits, custom molding of the ankle-foot orthosis to minimize contact pressures to the skin should be considered. If the prognosis is poor or recovery not forthcoming, the addition of dorsiflexion assist to the ankle-foot orthosis may help restore an even more normal gait than is achievable with a fixed ankle. With significant obesity or edema or in the face of severe polyneuropathy requiring special accommodative shoe wear, a dual upright ankle-foot orthosis may be indicated. The addition of dorsiflexion assist can easily be accomplished by adding springs to the posterior channels of a dual upright ankle-foot orthosis. The addition of dorsiflexion assist may be mandatory if the patient is having difficulty driving and right foot involvement is the cause. Most patients will have a stable and safe gait with an ankle-foot orthosis without additional gait aids, such as walkers, crutches, or canes; but when needed, gait training with any necessary gait aids should be ordered through physical therapy.

Because of the unbalanced weakness of the dorsiflexors, the lesser or unopposed plantar flexors must be actively stretched on a daily basis to prevent contracture development, which can occur in a matter of weeks. Similarly, the inverters may also need to be stretched in a home exercise program if the eversion function has been compromised. Splinting can also assist with contracture prevention and treatment.

As the muscle recovers function, which may occur during a few months if it is due to axonotmetic compression at the fibular head, strengthening can be initiated once manual muscle strength greater than 3/5 (antigravity strength but unable to take any resistance) returns. It is probably not prudent to exercise the newly reinnervated muscle to exhaustion, but moderate strengthening can be well tolerated. Patients may begin household ambulation without their ankle-foot orthoses before going long community distances. Patients should be advised to use their ankle-foot orthoses whenever prolonged walking is anticipated, even when manual muscle testing initially reveals 5/5 strength, because of early fatigue on initial strengthening.

Procedures

Although common peroneal neuropathy at the fibular head is rarely complicated by severe pain, sciatic or more distal superficial peroneal nerve stretch with axonotmesis can result in neuropathic pain. Medications focused on neuropathic pain are the mainstays of treatment, but additional nerve block is occasionally needed to resolve the associated pain adequately [44].

Surgery

When expected improvement does not occur or imaging studies reveal structures creating possible compromise of the nerve’s function, surgical exploration, compression relief, or neurotomy or resection of compromising tumors, synovial cysts or ganglia, or other structures may be needed [45–47]. For poor-prognosis, high sciatic near-complete or complete peroneal lesions, a new technique of transplanting some tibial nerve elements into the denervated tibialis anterior muscle has been successful, especially in children, in restoring function where previous footdrop existed [43]. Tendon transfers have also been used with variable success [45].

Potential Disease Complications

A common complication of peroneal neuropathy is footdrop and its deleterious effects on gait and balance, leading to falls and additional trauma. The sensory impairments place portions of the lateral leg and foot dorsum at risk for pressure ulcers or acute injuries that are not adequately treated because of lack of pain and sensation in those areas. If range of motion of the ankle is not adequately addressed, ankle contractures can result, further impairing gait and ankle-foot orthosis use.

Potential Treatment Complications

Any surgical treatment has the potential for infection, excessive bleeding, anesthetic death, and making the condition worse. Procedures likewise could worsen the condition and are used only when pain is intolerable and recalcitrant to medication interventions. Pain medications are most typically neuropathic pain–focused medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) and anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin). These have unique contraindications and side effect profiles. These medications must be initiated at a low dose and built up over time to minimize the occurrence of side effects. They are not used in an as-needed fashion like the more typical analgesics (such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) or opioids. Opioids tend to be less often used because of the chronic and neuropathic nature of most associated pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and opioid drugs also have unique side effect profiles. Physical dependence and development of tolerance with opioids must be considered because the neuropathic pain from peroneal nerve lesions is most often a chronic issue.