CHAPTER 74

Patellofemoral Syndrome

Rathi L. Joseph, DO; Joseph T. Alleva, MD, MBA; Thomas H. Hudgins, MD

Definition

Patellofemoral syndrome is the most common ailment involving the knee in both the athletic and the nonathletic population [3–5]. In sports medicine clinics, 25% of patients complaining of knee pain are diagnosed with this syndrome, and it affects women twice as often as men [3]. Yet despite the common occurrence of this disorder, there is no clear consensus on the definition, etiology, and pathophysiology [6]. The most common theory is that the syndrome is an overuse injury from repetitive overload at the patellofemoral joint. This increased stress results in physical and biomechanical changes of the patellofemoral joint [6]. The literature has focused on identification of risk factors leading to altered biomechanics that produce poor patellar tracking in the femoral trochlear groove and thus stress at the patellofemoral joint. Possible pain generators include the subchondral bone, retinacula, capsule, and synovial membrane [7]. Historically, the histologic diagnosis of chondromalacia, or deterioration of the cartilage, had been associated with patellofemoral syndrome. However, chondromalacia is poorly associated with the incidence of patellofemoral syndrome [5]. Electromyographic comparison of vastus medialis oblique (VMO) to vastus lateralis activation has shown delayed VMO activation in those patients with patellofemoral syndrome [8]. A pilot investigation has been done with 64-channel surface electromyography and motion capture to evaluate activation of the four heads of the quadriceps muscle in three dimensions. That study showed increased variability in the pattern of activation in the patellofemoral group compared with controls, resulting in altered patellar kinematics and loading of the patellar facets [9].

Symptoms

The patient with patellofemoral syndrome will complain of diffuse, vague ache of insidious onset [3]. The anterior knee is the most common location for pain, but some patients describe posterior knee discomfort in the popliteal fossa [4]. The discomfort is aggravated by prolonged sitting with knees flexed (“theater” sign) as well as on ascending or descending of stairs and squatting because these positions place the greatest force on the patellofemoral joint [10]. The patient may also experience pseudolocking when the knee momentarily locks in an extended position [11,12].

Physical Examination

The examination focuses on identification of risk factors that contribute to malalignment and rules out other pathologic processes associated with anterior knee pain. Tenderness to palpation at the medial and lateral borders of the patella may be appreciated [3]. A minimal effusion may also be present. The results of manual testing for intra-articular disease, such as the Lachman (anterior cruciate ligament) and McMurray (meniscal) maneuvers, will be negative.

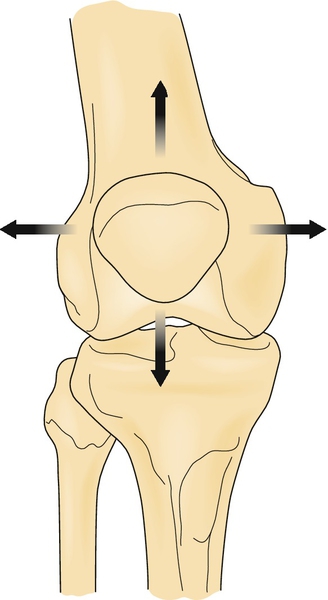

The presence of femoral anteversion, tibia internal rotation, excessive pronation at the foot, increased Q angle, and inflexibility of the hip flexors, quadriceps, iliotibial band, and gastrocnemius-soleus should be determined [13]. The patella position (baja or alta, internal or external rotation) should also be assessed with the patient sitting and standing. Each of these factors has either a direct or an indirect influence on the tracking of the patella with the femur (Fig. 74.1).

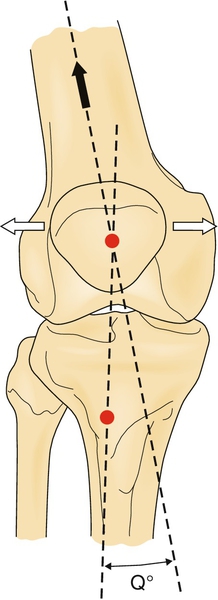

The Q angle is the intersection of a line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the patella with a line from the tibial tubercle to the patella (Fig. 74.2). This angle is typically less than 15 degrees in men and less than 20 degrees in women. An increased angle is associated with increased femoral anteversion and thus patellofemoral joint torsion [11]. However, a consensus on the importance of an increased Q angle is lacking [6]. Tight hip flexors, quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius-soleus will increase knee flexion and thus patellofemoral joint reaction force. A tight iliotibial band will increase the lateral pull of the patella through the lateral retinacular fibers [14,15]. Static hip strength was not shown to be a predisposing component of patellofemoral syndrome pain in women [16]. It is imperative to assess each of these components in the lower extremity kinetic chain to prescribe a tailored physical therapy program for each individual (Table 74.1).

Table 74.1

Causes of Altered Biomechanics

| Altered Biomechanics | Etiology |

| Increased knee flexion | Tight hip flexors, quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius-soleus |

| Lateral pull of patella | Tight iliotibial band, weak vastus medialis oblique |

| Femoral anteversion | Increased Q angle |

| Tibial internal rotation | Excessive foot pronation |

Functional Limitations

The patient with the patellofemoral syndrome will avoid activities that provoke the discomfort initially, such as stair climbing. Prolonged sitting in a car may be difficult. In chronic, progressive cases, ambulation may be enough to incite the pain, making all activities of daily living difficult.

Diagnostic Testing

Patellofemoral syndrome is a clinical diagnosis. Plain films may be used to evaluate Q angle and patella alta or baja. Advanced imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging, is reserved for recalcitrant cases that do not respond to conservative care to rule out intra-articular disease. Bone scintigrams revealed diffuse uptake in the patellofemoral joint in 50% of patients diagnosed with patellofemoral syndrome [17].

Treatment

Initial

As in other overuse injuries, the initial treatment focuses on decreasing pain. Icing is beneficial, particularly after activities. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be used in a judicious manner. Relative rest with non–weight-bearing aerobic activity may also be necessary. A neoprene knee sleeve with patella cutout is helpful to increase proprioceptive feedback. McConnell’s taping method can be used during the acute phase to reduce pain and to increase tolerance of a therapeutic exercise program, although it was less effective in patients with higher body mass index, larger lateral patellofemoral angle, and smaller Q angles [15,18–21]. Patella bracing was shown to reduce pain and to improve function in patients with patellofemoral syndrome but no more successfully than therapeutic exercise [22]. Of patients who had lower pain levels, wore less supportive footwear, had decreased ankle dorsiflexion range of motion, and reported an immediate reduction in pain when performing a single-leg squat with a foot orthosis, 78% found relief using foot orthoses at 12 weeks. In the same study, immediate pain relief while performing a single-leg squat with orthosis use was the greatest predictor of noncustomized prefabricated foot orthosis–related pain relief at 12 weeks [23].

Rehabilitation

With no consensus on the etiology and pathophysiology of patellofemoral syndrome, numerous treatment protocols and therapies have been proposed in the literature [24]. Nevertheless, most patients respond to a directed rehabilitation approach with therapeutic exercise [14,15]. The rehabilitation program should address deficiencies in strength, flexibility, and proprioception. Strength training can be achieved with both open kinetic chain and closed kinetic chain exercises. Open kinetic chain exercises occur when the distal link, the foot, is allowed to move freely in space, as in leg extensions. During closed kinetic chain exercises, the foot maintains contact with the ground, resulting in a multiarticular closed kinetic exercise, as in squatting or leg press [15]. Closed kinetic chain exercises are also less stressful than open chain exercises at the patellofemoral joint in the functional range of 0 to 45 degrees of knee flexion [25].

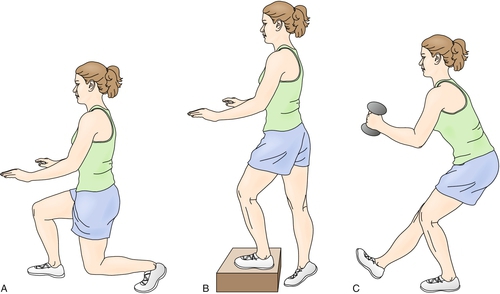

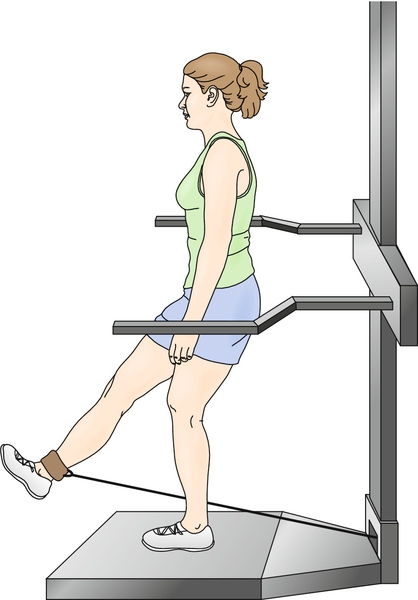

These exercises can be performed in multiple planes in a “functional” rehabilitation program (Figs. 74.3 and 74.4). This may entail having the patient perform a lunge (a closed kinetic chain exercise) in the coronal, sagittal, and transverse planes, simulating positions applied during activities. These exercises can also stress the patient’s balance by performance of the lunges with eyes closed. Through this functional or skill training, the patient is being prepared for all functional tasks by achieving efficient nerve-muscle interactions [10].

Many studies have focused on selective strengthening of the VMO as a dynamic medial stabilizer on the patella. Selective VMO strengthening may be achieved with combined hip adduction because the fibers of the VMO originate on the adductor magnus tendon and, to a lesser extent, the adductor longus. However, attempts at proving isolated recruitment of the VMO in relation to the vastus lateralis have failed [3]. Biofeedback and comprehensive McConnell-based physical therapy have been shown to improve motor control of the VMO as evidenced by altered firing patterns [26,27]. Nevertheless, quadriceps strengthening in general should be incorporated in the rehabilitation program through closed kinetic chain and functional exercises, which need to be incorporated in a long-term maintenance program.

Procedures

Injections are not indicated because this is primarily a maltracking phenomenon without a clear consensus on the pain generator.

Surgery

Surgery is rarely indicated, and a directed rehabilitation program is often successful [4]. However, several techniques have been illustrated in the literature. These include lateral retinacular release to decrease the lateral force, proximal and distal realignment procedures, and elevation of the tibial tubercle [1].

Potential Disease Complications

Recalcitrant chronic cases of anterior knee pain may show progressive degenerative changes at the patellofemoral joint, such as severe (grade IV) chondromalacia patellae.

Potential Treatment Complications

Risks of chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs include gastrointestinal bleeding, renal toxicity, hypertension, and other cardiovascular complications; thus, duration should be kept to a minimum. Systemic complication risk may be lessened by application of topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to the affected area only.

Overcompensation for the malalignment may occur with surgical techniques such as the lateral retinacular release. The surgeon may lyse too many fibers, leading to increased medial tracking. Many of the realignment procedures should also be reserved for the skeletally mature patient [1].