CHAPTER 73

Patellar Tendinopathy (Jumper’s Knee)

Rathi L. Joseph, DO; Joseph T. Alleva, MD, MBA; Thomas H. Hudgins, MD

Definition

Patellar tendinopathy or “jumper’s knee,” first described by Blazina and colleagues [1] in 1973, is primarily a chronic overuse injury of the patellar tendon resulting from excessive stress on the knee extensor mechanism. Athletes involved in sports requiring repetitive jumping, running, and kicking (e.g., volleyball, basketball, tennis, track) are at greatest risk. For example, volleyball players have an increased incidence compared with other sports of 22% to 39% [2]. Acceleration, deceleration, takeoff, and landing generate eccentric forces that can be three times greater than conventional concentric and static forces. These eccentric forces may exceed the inherent strength of the patellar tendon, resulting in microtears anywhere along the bone-tendon interface [2–4]. With continued stress, a cycle of microtearing, degeneration, and regeneration weakens the tendon and may lead to tendon rupture.

As in other overuse injuries, the predisposing factors in jumper’s knee include extrinsic causes, such as errors in training, and intrinsic causes, such as biomechanical flaws. Training errors include improper warm-up or cool-down, rapid increase in frequency or intensity of activity, and training on hard surfaces [3,4]. Biomechanical imbalances, such as tight hamstrings and excess femoral anteversion [3], and jumping mechanics [2,5] have been implicated as increased risk factors for development of patella tendinopathy (jumper’s knee). Finally, an increased incidence of Osgood-Schlatter disease and idiopathic anterior knee pain during adolescence has been identified in patients with jumper’s knee [3].

Because histologic studies of the patellar tendon reveal collagen degeneration with little or no evidence of acute inflammation, many authors argue that “patellar tendinopathy or tendinosis” is a more accurate description than “patellar tendinitis.” [6–8] This distinction has important implications for rehabilitation. In treatment of patellar tendinosis and other chronic overuse tendinopathies, the treatment team should emphasize restoration of function rather than control of inflammation. This is an overuse syndrome that has no age or gender predilection.

Symptoms

Patients typically report a dull, aching anterior knee pain, initially noted after a strenuous exercise session or competition, that is insidious in onset and well localized [7]. The bone-tendon junction at the inferior pole of the patella is most frequently affected (65% of cases), followed by the superior pole of the patella (25%) and the tibial tubercle (10%) [6]. Other symptoms may include stiffness or pain after prolonged sitting or climbing stairs [3], a feeling of swelling or fullness over the patella, and knee extensor weakness [1]. Mechanical symptoms of instability, such as locking, catching, and give-way weakness, are uncommon.

Four phases have been described in the progression of jumper’s knee: phase 1, pain is present after activity only and is not associated with functional impairment; phase 2, pain is present during and after activity but does not limit performance and resolves with rest; phase 3, pain is present continually and is associated with progressively impaired performance; and phase 4, complete tendon rupture [1].

As the disease progresses, the pain becomes sharper, more severe, and constant (present not only with athletic endeavor but also with walking and other everyday activities). If it is not treated, the disorder may result in tendon rupture, a sudden painful event associated with immediate inability to extend the knee [7].

Physical Examination

The hallmark of jumper’s knee is tenderness at the site of involvement, usually the inferior pole of the patella [7]. This sign is best elicited on palpation of the knee in full extension [7], and the pain typically increases when the knee is extended against resistance [3]. On occasion, there may be swelling of the tendon or the fat pad, although a frank knee joint effusion is not typically present [3]. Mild patellofemoral crepitus and pain with compression of the patellofemoral joint have been noted [3]. In advanced disease, patients may have quadriceps atrophy without detectable weakness on manual muscle testing and hamstring tightness [3,7]. Test results for knee ligamentous laxity are negative. The examiner should also expect normal findings on neurologic examination.

Functional Limitations

Most patients experience little functional limitation in the early stages of jumper’s knee. As the disease progresses, however, increasing disability from persistent pain and inhibition of knee extension impairs athletic performance. Eventually, walking and the ability to perform basic activities of living, such as ascending or descending stairs, may be compromised. In the event of patellar tendon rupture, complete functional impairment with inability to extend the affected knee, limiting weight bearing and ambulation, necessitates surgical repair.

Diagnostic Testing

Radiographic changes are rarely present during the first 6 months of patellar tendinopathy, limiting the usefulness of radiographs during initial evaluation [4]. When radiography is performed, the examination generally includes anteroposterior, lateral, intercondylar, and skyline (or sunrise) tracking patellar views [3]. Documented findings include radiolucency at the site of involvement, elongation of the involved pole, and occasionally a fracture at the junction of the elongation with the main portion of the patella. On occasion, calcification of the involved tendon and irregularity or even avulsion of the involved pole may be seen [1].

Ultrasonography has the advantage of allowing early diagnosis and dynamic imaging of the tendon while remaining inexpensive, noninvasive, reproducible, and sensitive to changes as small as 0.1 mm [4]. Some authors believe ultrasonography to be the preferred method for evaluation of jumper’s knee. It has been used to confirm the diagnosis, to guide steroid injections, and to observe tendons after surgery [4]. It should be considered in cases that do not respond to a trial of conservative treatment after 4 to 6 weeks and when the diagnosis is questioned. Findings on ultrasound examination include thickening of the tendon [4,9]. A hypoechoic focal lesion at the area of greatest thickening correlates well with the lesion on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography, and histologic examination [3,10]. However, critics of ultrasonography have noted abnormalities in asymptomatic athletes. This phenomenon may be explained by a preclinical or postclinical stage of the disease [4]. Plain MRI, MRI with intravenous administration of gadolinium, and MRI arthrography with gadolinium have been used to corroborate the clinical diagnosis of jumper’s knee. Increased thickening of the patellar tendon on MRI is present in all patients resistant to conservative therapy [11,12]. MRI is also advantageous in excluding other intrinsic joint disease. MRI arthrography is particularly useful in examining the chondral surfaces of the patella and femur when osteochondritis dissecans or other pathologic processes in these areas are suspected. Before advanced imaging, we recommend simple radiographic examination with three views of the knee to rule out bone pathologic changes and to evaluate joint space. If patients do not respond to physical therapy in 4 to 6 weeks, ultrasound examination is the preferred study at that time to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Initial

Because the syndrome is progressive and associated with difficult and slow rehabilitation, the importance of early diagnosis and treatment cannot be overemphasized [13]. Initial interventions include control of pain with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ice, and relative rest. Passive modalities such as ultrasound and iontophoresis with corticosteroid preparation are also used judiciously to control pain.

Rehabilitation

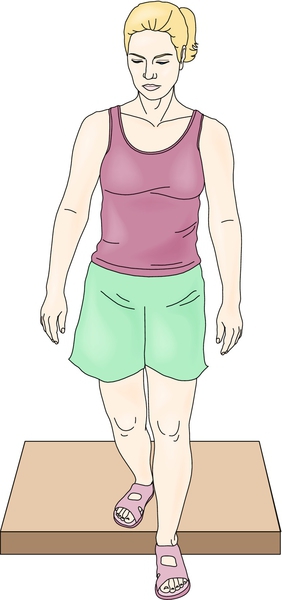

A comprehensive rehabilitation program should address the biomechanical flaws found on the musculoskeletal examination. These include the functional deficits (inflexibilities that lead to altered biomechanics) and subclinical adaptations (substitution patterns that compensate for the functional deficits) [14]. This approach may be used in addressing all overuse syndromes. In patellar tendinopathy, hamstring and quadriceps tightness and weakness need to be addressed [14]. As the rehabilitation program advances and pain abates, eccentric strengthening exercises should be emphasized. This type of strengthening exercise is optimal for rehabilitation of tendinopathies because it places maximal tensile load on the muscle and tendon unit (Fig. 73.1) [15]. There is a paucity of randomized controlled studies supporting this type of exercise; however, eccentric strengthening is commonly recommended [16]. This type of exercise may provoke pain initially, given the increased load placed on the muscle-tendon unit. The final phase of rehabilitation should also encompass sports-specific drills and training. Knee supports and counterforce straps have been used to alleviate pain and to change the force dynamics through the patellar tendon with good results [4,17].

Procedures

Some authors recommend a peritendinous injection of steroid if noninvasive conservative therapy fails [3,4]. This is performed with ultrasound guidance to ensure accurate placement of the needle. Decreased pain with injection of the fat pad rather than of the tendon itself has been documented [3]. Because histologic studies have shown a minimal inflammatory component in surgical specimens, the mechanism of action of these approaches is unknown [4]. In addition, studies have associated tendon ruptures with steroid injection [4,18]. The efficacy of prolotherapy (10% dextrose) in patellar tendinopathy has not been studied [19]. Some anecdotal evidence supports the use of protein-rich plasma therapy [20].

Surgery

In the advanced stage of jumper’s knee, if a well-documented conservative therapy trial has failed or if the tendon ruptures, surgery is indicated. Several approaches have had mixed success; resection of the tendon disease with resuturing of the tendon is most often cited, and authors report 77% to 93% good or excellent results [21,22].

However, when more invasive treatments, such as injections or surgery, are contemplated, it is incumbent on the practitioner to ensure that a comprehensive rehabilitation program has been followed thoroughly, as outlined earlier, before one declares a “conservative management failure.” Criteria for conservative management failure are often ill-defined in the literature. In our experience, invasive procedures are rarely necessary for the management of jumper’s knee. Postoperative rehabilitation begins with isometric strengthening of the quadriceps, restoring range of motion and advancing to eccentric strengthening in 6 to 12 weeks.

Potential Disease Complications

Stress reaction of the patella, stress fracture, and patellar tendon rupture are some of the advanced complications. Others include formation of accessory ossicles, avulsion apophysis, and bone growth acceleration or arrest in adolescents [23].

Potential Treatment Complications

Gastrointestinal bleeding and renal side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are well documented. Complications of corticosteroid injections include bleeding, infection, and soft tissue atrophy at the site of injection. Tendon weakening with possible increased incidence of tendon rupture has also been cited. Surgery can lead to inadvertent tibial or peroneal nerve injury.