Pulmonary Artery Catheter Insertion (Perform)

Pulmonary Artery Catheter Insertion (Perform)

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge of the normal anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system is needed.

• Knowledge of the normal anatomy and physiology of the vasculature and adjacent structures of the neck is necessary.

• Knowledge of the principles of sterile technique is essential.

• Clinical and technical competence in central line insertion and suturing is important.

• Clinical and technical competence in pulmonary artery (PA) catheter insertion is essential. Competence in chest radiograph interpretation is needed.

• Basic dysrhythmia recognition and treatment of life-threatening dysrhythmias should be understood.

• Advanced cardiac life support knowledge and skills are needed.

• Understanding of PA pressure monitoring (see Procedure 73) is necessary.

• Hemodynamic information obtained with a PA catheter is routinely used to guide therapeutic interventions, including administration of fluids and diuretics and titration of vasoactive and inotropic medications.1–3,10,11

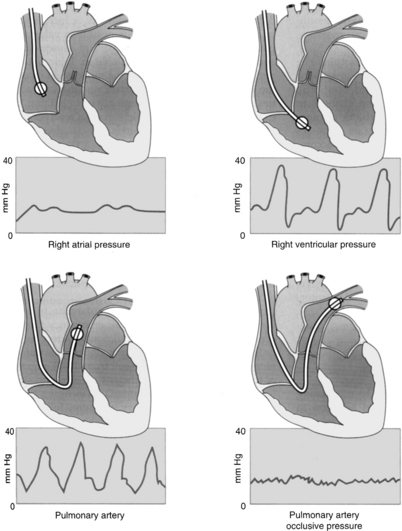

• Understanding is needed of a, c, and v waves. The a wave reflects atrial contraction. The c wave reflects closure of the atrioventricular valves. The v wave reflects passive filling of the atria during ventricular systole.

• Information can be gathered regarding cardiac output (CO), cardiac index (CI), systemic vascular resistance (SVR), pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), stroke volume/stroke index (SV/SI), mixed venous oxygenation (SvO2), right heart pressures (pulmonary artery pressure [PAP] and right atrial pressure [RAP]), and a reflection of left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) and volume (LVEDV). Also, information regarding right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) and end-diastolic volume (RVEDV) can be determined with certain catheters.

• CO and SvO2 can be obtained intermittently or continuously.

• There are several types of PA catheters with different functions (e.g., pacing, mixed venous oxygenation saturation monitoring, continuous CO or right ventricular volume monitoring). Catheter selection is based on patient need.

• The PA catheter contains a proximal lumen port, a distal lumen port, a thermistor lumen port, and a balloon inflation lumen port (see Fig. 73-1). Some catheters also have additional infusion ports that can be used for the infusion of medications and intravenous fluids.

• The distal lumen port is used for monitoring systolic, diastolic, and mean pressures in the PA. The proximal lumen (or injectate) port is used for monitoring the right atrial pressure and injection of the solution used to obtain cardiac outputs. The balloon inflation lumen port is used to obtain the pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP) or pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP).

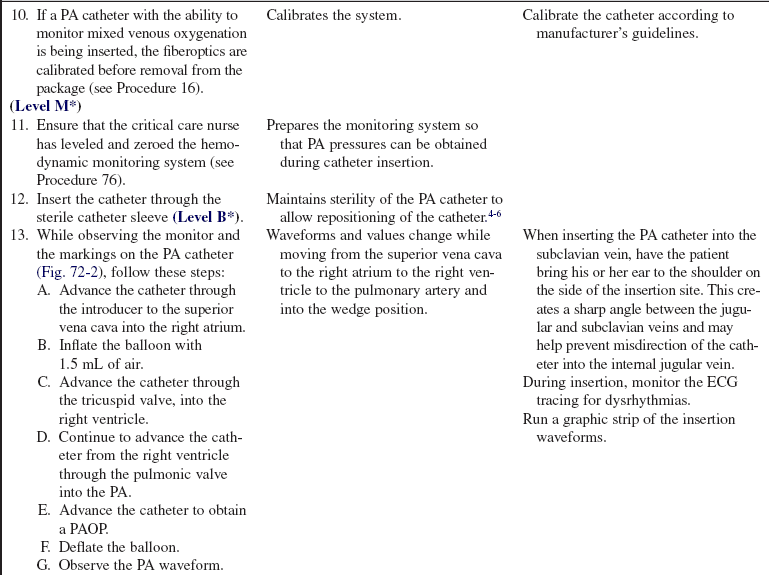

• The standard 7.5F PA catheter is 110 cm long and has black markings at 10-cm increments and wide black markings at 50-cm increments to facilitate insertion and positioning (see Fig. 73-1). The catheter should reach the PA after advancing 40 to 55 cm from the internal jugular vein, 35 to 50 cm from the subclavian vein, 60 cm from the femoral vein, 70 cm from the right antecubital fossa, and 80 cm from the left antecubital fossa.

• Central venous access may be obtained in a variety of places (see Procedure 81).

• The right subclavian vein is a more direct route than the left subclavian vein for placement of a PA catheter because the catheter does not cross the midline of the thorax.1,2,9,13

• Use of an internal jugular vein minimizes the risk for a pneumothorax. The preferred site for catheter insertion is the right internal jugular vein. The right internal jugular vein is a “straight shot” to the right atrium.13

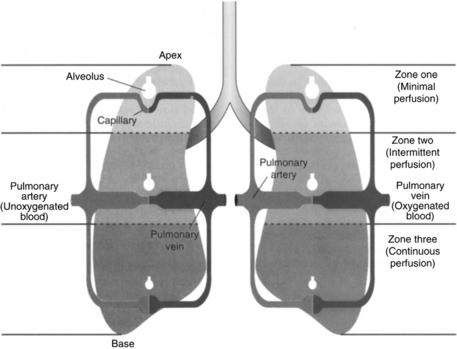

• Knowledge of West’s lung zones helps attain proper placement of the PA catheter (Fig. 72-1).

The PA catheter should lie in lung zone 3, below the level of the left atrium in the dependent portion of the lung.19 In lung zone 3, both arterial and venous pressures exceed alveolar pressure and PAOP reflects vascular pressures rather than alveolar pressures.19

• Common indications for insertion of a PA catheter include the following1,2,7,8,12,14,16:

Acute coronary syndrome or myocardial infarction (MI) complicated by hemodynamic instability, heart failure, cardiogenic shock, mitral regurgitation, ventral septal rupture, subacute cardiac rupture with tamponade, postinfarction ischemia, papillary muscle rupture, or severe heart failure (e.g., cardiomyopathy, constrictive pericarditis)

Acute coronary syndrome or myocardial infarction (MI) complicated by hemodynamic instability, heart failure, cardiogenic shock, mitral regurgitation, ventral septal rupture, subacute cardiac rupture with tamponade, postinfarction ischemia, papillary muscle rupture, or severe heart failure (e.g., cardiomyopathy, constrictive pericarditis)

Hypotension unresponsive to fluid replacement or with heart failure

Hypotension unresponsive to fluid replacement or with heart failure

Cardiac tamponade, significant dysrhythmias, right ventricular infarct, acute pulmonary embolism, and tricuspid insufficiency

Cardiac tamponade, significant dysrhythmias, right ventricular infarct, acute pulmonary embolism, and tricuspid insufficiency

Anesthesia in cardiac surgery with any of the following:

Anesthesia in cardiac surgery with any of the following:

Resection of ventricular aneurysm

Resection of ventricular aneurysm

Coronary artery bypass graft (reoperation)

Coronary artery bypass graft (reoperation)

Coronary artery bypass graft (left main or complex coronary disease)

Coronary artery bypass graft (left main or complex coronary disease)

Unstable angina that necessitates vasodilator therapy

Unstable angina that necessitates vasodilator therapy

Heart failure unresponsive to conventional therapy (cardiomyopathy)1,2,18

Heart failure unresponsive to conventional therapy (cardiomyopathy)1,2,18

Pulmonary hypertension during acute medication therapy

Pulmonary hypertension during acute medication therapy

Distinguishing cardiogenic from noncardiogenic pulmonary edema

Distinguishing cardiogenic from noncardiogenic pulmonary edema

Constrictive pericarditis or cardiac tamponade

Constrictive pericarditis or cardiac tamponade

Evaluation of pulmonary hypertension for a precardiac transplant workup

Evaluation of pulmonary hypertension for a precardiac transplant workup

Acute respiratory failure with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases

Acute respiratory failure with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases

Optimization of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and volume therapy in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome1

Optimization of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and volume therapy in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome1

Patients who need intraaortic balloon pump therapy

Patients who need intraaortic balloon pump therapy

Critically ill pregnant patients (e.g., severe preeclampsia with unresponsive hypertension, pulmonary edema, persistent oliguria)

Critically ill pregnant patients (e.g., severe preeclampsia with unresponsive hypertension, pulmonary edema, persistent oliguria)

• Relative contraindications to PA catheter insertion include the following:

EQUIPMENT

• Percutaneous sheath introducer kit and sterile catheter sleeve

• PA catheter (non–heparin-coated catheters and latex-free PA catheters are available)

• Bedside hemodynamic monitoring system with pressure and cardiac output monitoring capability

• Pressure modules and cables for interface with the monitor

• Cardiac output cable with a thermistor/injectate sensor

• Pressure transducer system, including flush solution recommended according to institution standard, a pressure bag or device, pressure tubing with transducers, and flush device (see Procedure 76)

• Sterile normal saline intravenous fluid for flushing the introducer and catheter infusion ports

• Antiseptic solution (e.g., 2% chlorhexidine-based preparation)

• Head covering, fluid-shield masks, sterile gowns, sterile gloves, nonsterile gloves, and sterile drapes

• 1% lidocaine without epinephrine

• Sterile water or normal saline solution

• Chlorhexidine-impregnated sponge

• Stopcocks (may be included with the pressure tubing systems)

Additional equipment to have available as needed includes the following:

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure and the reason for the PA catheter insertion.  Rationale: Explanation decreases patient and family anxiety.

Rationale: Explanation decreases patient and family anxiety.

• Explain the need for sterile technique and explain that the patient’s face may be covered.  Rationale: The explanation decreases patient anxiety and elicits cooperation.

Rationale: The explanation decreases patient anxiety and elicits cooperation.

• Inform the patient of expected benefits and potential risks.  Rationale: The patient is given information to make an informed decision.

Rationale: The patient is given information to make an informed decision.

• Explain the patient’s expected participation during the procedure.  Rationale: Patient assistance is encouraged.

Rationale: Patient assistance is encouraged.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Determine the patient’s medical history of cervical disk disease or difficulty with vascular access.  Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

• Determine the patient’s medical history of pneumothorax or emphysema.  Rationale: Patients with emphysematous lungs may be at higher risk for puncture and pneumothorax depending on the approach.

Rationale: Patients with emphysematous lungs may be at higher risk for puncture and pneumothorax depending on the approach.

• Determine the patient’s medical history of anomalous veins.  Rationale: Patients may have a history of dextrocardia or transposition of the great vessels, which leads to greater difficulty in catheter placement.

Rationale: Patients may have a history of dextrocardia or transposition of the great vessels, which leads to greater difficulty in catheter placement.

• Assess the intended insertion site.  Rationale: Scar tissue may impede placement of the catheter.

Rationale: Scar tissue may impede placement of the catheter.

• Assess the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary status.  Rationale: Some patients may not tolerate supine or Trendelenburg’s position for extended periods.

Rationale: Some patients may not tolerate supine or Trendelenburg’s position for extended periods.

• Assess vital signs and pulse oximetry.  Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

• Assess for electrolyte imbalances (potassium, magnesium, and calcium).  Rationale: Electrolyte imbalances may increase cardiac irritability.

Rationale: Electrolyte imbalances may increase cardiac irritability.

• Assess the electrocardiogram (ECG) for left bundle-branch block.  Rationale: Right bundle-branch block has been associated with PA catheter insertion. Caution should be used because complete heart block may ensue.9,15

Rationale: Right bundle-branch block has been associated with PA catheter insertion. Caution should be used because complete heart block may ensue.9,15

• Assess for heparin and latex sensitivity or allergy.  Rationale: PA catheters are heparin-bonded and contain latex. If the patient has a heparin allergy or a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, consider the use of a non–heparin-coated catheter.15,17 If the patient has a latex allergy, use a latex-free PA catheter.

Rationale: PA catheters are heparin-bonded and contain latex. If the patient has a heparin allergy or a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, consider the use of a non–heparin-coated catheter.15,17 If the patient has a latex allergy, use a latex-free PA catheter.

• Assess for a coagulopathic state and determine whether the patient has recently received anticoagulant or thrombolytic therapy.  Rationale: These patients are more likely to have complications related to bleeding and may need interventions before insertion of the PA catheter.

Rationale: These patients are more likely to have complications related to bleeding and may need interventions before insertion of the PA catheter.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Obtain informed consent.  Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of a patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of a patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Place the patient in the supine position and prepare the area with the antiseptic solution (e.g., 2% chlorhexidine–based preparation).13,15  Rationale: The site access is prepared for PA catheter insertion.

Rationale: The site access is prepared for PA catheter insertion.

• Prescribe sedation or analgesics as needed.  Rationale: Sedation and analgesics minimize anxiety and discomfort. Movement of the patient may inhibit insertion of the PA catheter.

Rationale: Sedation and analgesics minimize anxiety and discomfort. Movement of the patient may inhibit insertion of the PA catheter.

• If the patient is obese or muscular and the preferred site is the internal jugular vein or subclavian vein, place a towel posteriorly between the shoulder blades.  Rationale: This action helps extend the neck and provide better access to the subclavian and internal jugular veins.

Rationale: This action helps extend the neck and provide better access to the subclavian and internal jugular veins.

• If the brachial vein is used, stabilize the arm on a padded arm board.  Rationale: Visualization of the brachial vein is aided.

Rationale: Visualization of the brachial vein is aided.

• Drape sterile drapes over the prepared area.  Rationale: Sterile drapes provide an aseptic work area.

Rationale: Sterile drapes provide an aseptic work area.

References

![]() 1. American Society of Anesthesiology. Practice guidelines for pulmonary artery catheters. Anesthesiology. 2003; 99:988–1014.

1. American Society of Anesthesiology. Practice guidelines for pulmonary artery catheters. Anesthesiology. 2003; 99:988–1014.

![]() 2. Amin, DK, Shah, PK, Swan, HJC. Deciding when hemodynamic monitoring is appropriate. J Crit Illn. 1993; 8:1053–1061.

2. Amin, DK, Shah, PK, Swan, HJC. Deciding when hemodynamic monitoring is appropriate. J Crit Illn. 1993; 8:1053–1061.

![]() 3. Bridges, EJ, Woods, SL, Pulmonary artery measurement. state of the art. Heart Lung 1993; 22:99–111.

3. Bridges, EJ, Woods, SL, Pulmonary artery measurement. state of the art. Heart Lung 1993; 22:99–111.

![]() 4. Burns, D, Burns, D, Shively, M. Critical care nurses’ knowledge of pulmonary artery catheters. Am J Crit Care. 1996; 5:49–54.

4. Burns, D, Burns, D, Shively, M. Critical care nurses’ knowledge of pulmonary artery catheters. Am J Crit Care. 1996; 5:49–54.

![]() 5. Cohen, Y, et al, The “hands-off” catheter and the prevention of systemic infections associated with pulmonary artery catheter. a prospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157:284–287.

5. Cohen, Y, et al, The “hands-off” catheter and the prevention of systemic infections associated with pulmonary artery catheter. a prospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157:284–287.

6. Corcoran, TB, Grape, S, Duff, O, et al, The pulmonary artery catheter sleeve. protective or infective. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009; 37(2):290–295.

![]() 7. Darovic, GO, Pulmonary artery pressure monitoring. Hemodynamic monitoring: invasive and noninvasive clinical application. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2002.

7. Darovic, GO, Pulmonary artery pressure monitoring. Hemodynamic monitoring: invasive and noninvasive clinical application. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2002.

![]() 8. Davis, D, et al, Impact of formal continuing medical education. do conferences, workshops, rounds and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes. JAMA 1999; 282:867–874.

8. Davis, D, et al, Impact of formal continuing medical education. do conferences, workshops, rounds and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes. JAMA 1999; 282:867–874.

![]() 9. Eggimann, P, et al. Impact of a prevention strategy targeted at vascular-access care on incidence of infections acquired in intensive care. Lancet. 2000; 355:1864–1868.

9. Eggimann, P, et al. Impact of a prevention strategy targeted at vascular-access care on incidence of infections acquired in intensive care. Lancet. 2000; 355:1864–1868.

![]() 10. Herbert, KA, Glancy, DL. Indications for Swan-Ganz catheterization. Heart Dis Stroke. 1994; 3:196–200.

10. Herbert, KA, Glancy, DL. Indications for Swan-Ganz catheterization. Heart Dis Stroke. 1994; 3:196–200.

![]() 11. Iberti, TJ, et al. A multicenter study of physicians’ knowledge of the pulmonary artery catheter. JAMA. 1990; 22:2928–2933.

11. Iberti, TJ, et al. A multicenter study of physicians’ knowledge of the pulmonary artery catheter. JAMA. 1990; 22:2928–2933.

![]() 12. Iberti, TJ, et al. Assessment of critical care nurses’ knowledge of the pulmonary artery catheter. Crit Care Med. 1994; 22:1674–1678.

12. Iberti, TJ, et al. Assessment of critical care nurses’ knowledge of the pulmonary artery catheter. Crit Care Med. 1994; 22:1674–1678.

13. Lorente, L, Henry, C, Martin, M, et al. Central venous catheter-related infection in a prospective and observational study of 2,595 catheters. Crit Care. 2005; 9:R631–R635.

![]() 14. Morris, AH, Chapman, RH. Wedge pressure confirmation by aspiration of pulmonary capillary blood. Crit Care Med. 1985; 13:756–759.

14. Morris, AH, Chapman, RH. Wedge pressure confirmation by aspiration of pulmonary capillary blood. Crit Care Med. 1985; 13:756–759.

![]() 15. O’Grady, NP, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am J Infect Control. 2002; 30:476–489.

15. O’Grady, NP, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am J Infect Control. 2002; 30:476–489.

![]() 16. Pulmonary Artery Consensus Conference Participants, Pulmonary Artery Catheter Consensus Conference . consensus statement. Crit Care Med 1997; 25:910–925.

16. Pulmonary Artery Consensus Conference Participants, Pulmonary Artery Catheter Consensus Conference . consensus statement. Crit Care Med 1997; 25:910–925.

![]() 17. Silver, D, Kapsch, DN, Tsoi, EK. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, thrombosis, and hemorrhage. Ann Surg. 1983; 198:301–306.

17. Silver, D, Kapsch, DN, Tsoi, EK. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, thrombosis, and hemorrhage. Ann Surg. 1983; 198:301–306.

![]() 18. Sandham, JD, Hull, LD, Brant, LF, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of the use of pulmonary-artery catheters in high-risk surgical patients. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:5–14.

18. Sandham, JD, Hull, LD, Brant, LF, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of the use of pulmonary-artery catheters in high-risk surgical patients. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:5–14.

![]() 19. West, JB, Dollery, CT, Naimark, A, Distribution of blood flow in isolated lung. relation to vascular and alveolar pressure. J Appl Physiol 1964; 19:713–724.

19. West, JB, Dollery, CT, Naimark, A, Distribution of blood flow in isolated lung. relation to vascular and alveolar pressure. J Appl Physiol 1964; 19:713–724.

Ahrens, TS, Taylor, LK. Hemodynamic waveform analysis. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1992.

American Association of Critical Care Nurses, Evaluation of the effects of heparinized and nonheparinized flush solutions on the patency of arterial pressure monitoring lines. the AACN Thunder Project. Am J Crit Care 1993; 2:3–15.

Amin, DK, Shah, PK, Swan, HJC, The Swan-Ganz catheter. techniques for avoiding common errors. J Crit Illn 1993; 8:1263–1271.

Amin, DK, Shah, PK, Swan, HJC. The technique of inserting a Swan-Ganz catheter. J Crit Illn. 1993; 8:1147–1156.

Baxter, JK, et al, Effectiveness of right heart catheterization. time for a randomized trial. JAMA 1997; 277:108.

Blot, F, Chachaty, E, Raynard, B, et al. Mechanisms and risk factors for infection of pulmonary artery catheters and -introducer sheaths in cancer patients admitted to an -intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 2001; 48(4):289–297.

Chernow, B, Pulmonary artery flotation catheters. a statement by the American College of Chest Physicians and the American Thoracic Society. Chest 1997; 111:261.

Connors, AF, et al. The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. JAMA. 1996; 276:889–897.

Daily, EK, Schroeder, JS. Techniques in bedside hemodynamic monitoring, ed 5. St Louis: Mosby; 1994.

Darovic, GO, Hemodynamic monitoring. invasive and noninvasive clinical application. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2002.

Friesinger, GC, Williams, SV, ACP/ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Privileges in Cardiology. Clinical competence in hemodynamic monitoring. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990; 15:1460.

Gardner, PE, Bridges, EJ. Hemodynamic monitoring. In: Woods SL, et al, eds. Cardiac nursing. ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1995:424–458.

Ginosar, Y, Pizov, R, Sprung, CL, Arterial and pulmonary artery catheters. In Critical care medicine. Mosby, St Louis, 1995.

Hadian, M, Pinsky, MR, Evidence-based review of the use of the pulmonary artery catheter. impact, data and complications. Crit Care. 2006; 10(Suppl 3):S11–S18.

Harvey, S, et al, Assessment of the clinical effectiveness of pulmonary artery catheters in management of patients in intensive care (PAC-Man). a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2005; 366(9484):472–477.

Harvey, S, et al. Pulmonary artery catheters for adult patients in intensive care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; 19:3. [July].

Keckeisen, M, Protocols for practice. hemodynamic monitoring series: pulmonary artery pressure monitoring. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, Aliso Viejo, CA, 1997.

Leeper, B, Monitoring right ventricular volumes. a paradigm shift. AACN Clin Issues Adv Pract Acute Crit Care 2003; 14:208–219.

Pinsky, MR. Hemodynamic monitoring over the past 10 years. Crit Care. 2006; 10:117–119.

Pulmonary Artery Catheter Consensus Conference Participants, Pulmonary Artery Catheter Consensus Conference. consensus statement. Crit Care Med 1997; 25:910–925.

Rapoprot, LJ, Teres, D, Steingrub, J. Patient characteristics and ICU organizational factors that influencing of frequency of PA catheter. JAMA. 2000; 283:2555.

Swan, JHC. What role today for hemodynamic monitoring. J Crit Illn. 1993; 8:1043–1050.

Swan, JHC, Ganz, W, Forrester, JS. Catheterization of the heart in a man with the use of a flow-directed balloon-tipped catheter. N Engl J Med. 1970; 280:447.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Task Force on Pulmonary Artery Catheterization. Practice guidelines for pulmonary catheterization. Anesthesiology. 1993; 78:380–394.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Clinical Trial Network, Wheeler AP, et al. Pulmonary artery vs central venous catheter to guide treatment of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(21):2213–2224.

Tuggle, D, Optimizing hemodynamics. strategies for fluid -and medication titration in shock, AACN advanced -critical care nursing. Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2009:1099–1133.

Wiener, R, Welch, H. Trends in the use of the pulmonary artery catheter in the United States 1993-2004. JAMA. 2007; 298(4):423–429.