CHAPTER 72

Meniscal Injuries

Paul Lento, MD; Venu Akuthota, MD

Definition

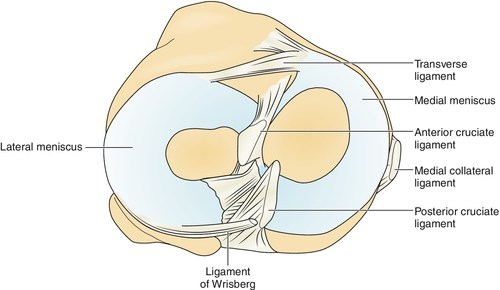

The menisci serve important roles in maintaining proper joint health, stability, and function [1]. The anatomy of the medial and lateral menisci helps explain functional biomechanics. Viewed from above, the medial meniscus appears C shaped and the lateral meniscus appears O shaped (Fig. 72.1)[1]. Each meniscus is thick and convex at its periphery (the horns) but becomes thin and concave at its center. This contouring serves to provide a larger area for the rounded femoral condyles and the relatively flat tibia. Menisci do not move in isolation. They are connected by ligaments to each other anteriorly and to the anterior cruciate ligament, the patella, the femur, and the tibia [2,3].

The medial meniscus is less mobile than the lateral meniscus. This is due to its firm connections to the knee joint capsule and the medial collateral ligament. This decreased mobility, in conjunction with the fact that the medial meniscus is wider posteriorly, is cited as the usual reason for the higher incidence of tears within the medial meniscus than within the lateral meniscus [1]. The semimembranosus muscle (through attachments from the joint capsule) helps retract the medial meniscus posteriorly, serving to avoid entrapment and injury to the medial meniscus as the knee is flexed [3]. The lateral meniscus is not as adherent to the joint capsule. Unlike the medial meniscus, the lateral meniscus does not attach to its respective collateral ligament. The posterolateral aspect of the lateral meniscus is separated from the capsule by the popliteus tendon. Therefore the lateral meniscus is more mobile than the medial meniscus [1,3]. The attachment of the popliteus tendon to the posterolateral meniscus ensures dynamic retraction of the lateral meniscus when the knee internally rotates to return out of the screw-home mechanism [2]. Therefore both the medial and the lateral menisci, by having attachments to muscle structures, share a common mechanism that helps avoid injury.

The architecture of the vascular supply to the meniscus has important implications for healing [1,4]. Capillaries penetrate the menisci from the periphery to provide nourishment. After 18 months of age, as weight bearing increases, the blood supply to the central part of the menisci recedes. In fact, research has shown that eventually only the peripheral 10% to 30% of the menisci, or the red zone, receives this capillary network (Fig. 72.2) [5]. Therefore the central and internal portion or white zone of these fibrocartilaginous structures becomes avascular with age, relying on nutrition received through diffusion from the synovial fluid. Because of this vascular arrangement, the peripheral meniscus is more likely to heal than are the central and posterolateral aspects [4].

The primary but not sole function of the menisci is to distribute forces across the knee joint and to enhance stability [1,6–8]. Multiple studies have shown that the ability of the joint to transmit loads is significantly reduced if the meniscus is partially or wholly removed [1,6,7,9]. Fairbank [10] published a seminal article in 1948 suggesting that the menisci are vital in protecting the articular surfaces. He reported that individuals who had undergone total meniscectomies demonstrated premature osteoarthritis.

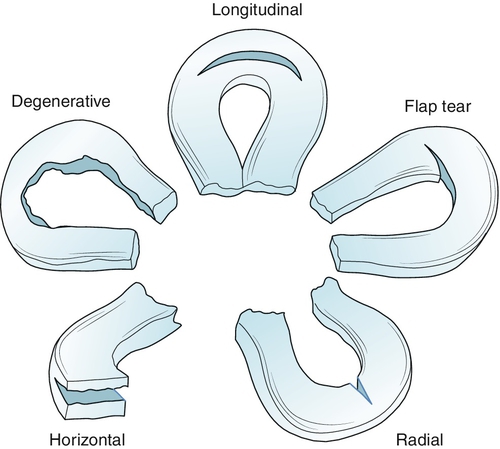

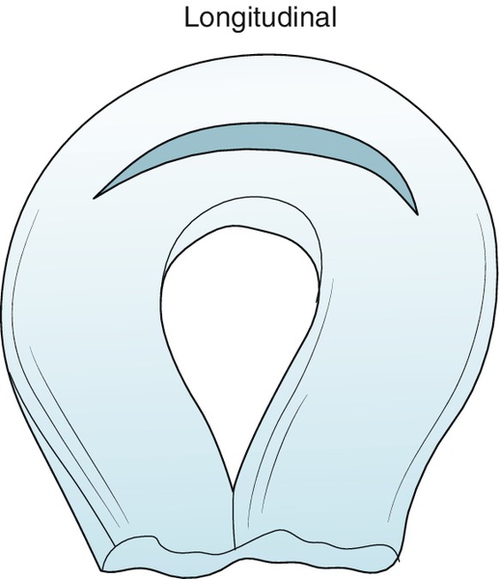

Meniscal tears are classified by their complexity, plane of rupture, direction, location, and overall shape. Tears are commonly defined as vertical, horizontal, longitudinal, or oblique in relation to the tibial surface (Fig. 72.3)[11]. Most meniscal tears in young patients will be vertical-longitudinal, whereas horizontal cleavage tears are more commonly found in older patients [12]. The bucket-handle tear is the most common type of vertical (or longitudinal) tear [13] (Fig. 72.4). Tears are also described as complete, full-thickness or partial tears. Complete, full-thickness tears are so named as they extend from the tibial to femoral surfaces. In addition, medial meniscus tears outnumber lateral meniscus tears from 2:1 to 5:1 [14,15].

Meniscal injuries may result from an acute injury or from gradual degeneration with aging [16]. Vertical tears (e.g., bucket-handle tears) tend to occur acutely in individuals 20 to 30 years of age and are usually located in the posterior two thirds of the meniscus [13,17]. Sports commonly associated with meniscal injuries are soccer, football, basketball, baseball, wrestling, skiing, rugby, and lacrosse. Injury commonly occurs when an axial load is transmitted through a flexed or extended knee that is simultaneously rotating [16]. Degenerative tears, in contrast, are usually horizontal and are seen in older individuals with concomitant degenerative joint changes [13,18].

On the basis of arthroscopic examination, the majority of acute peripheral meniscal injuries are associated with some degree of occult anterior cruciate ligament laxity [19]. In addition, true anterior cruciate ligament tears are associated with lesions of the posterior horns of the menisci [19]. Lateral meniscal tears appear to occur with more frequency with acute anterior cruciate ligament injuries, whereas medial meniscal tears have a higher incidence with chronic anterior cruciate ligament injuries. With chronic anterior cruciate ligament injuries, the medial meniscus may be more frequently damaged because its posterior horn serves as an important secondary stabilizer of anterior-posterior instability [20].

Symptoms

The history will help diagnose a meniscal injury 75% of the time [12,21]. Young patients who experience meniscal tears will recall the mechanism of injury 80% to 90% of the time and may report a “pop” or a “snap” at the time of injury. Deep knee bending activities are often painful, and mechanical locking may be present in 30% of patients [22]. Bucket-handle tears should be suspected in cases of mechanical locking with loss of full extension [16]. If locking is reported approximately 1 day after the injury, this may be due to “pseudolocking,” which results from hamstring contracture [14]. Knee hemarthrosis may also occur acutely, especially if the vascularized, peripheral portion of the meniscus is involved. In fact, 20% of all acute traumatic knee hemarthroses are caused by isolated meniscal injury [23]. More typically, however, knee swelling occurs approximately 1 day later as the meniscal tear causes mechanical irritation within the intra-articular space, creating a reactive effusion. Typically, this effusion is secondary to a lesion in the central portion of the meniscus [16].

In contrast, degenerative meniscal tears are not usually associated with a history of trauma. In fact, the mechanism of injury, which may not be reported by the patient, can be simple daily activities, such as rising from a chair and pivoting on a planted foot [16]. Patients with degenerative tears often also report recurrent knee swelling, particularly after activity.

Physical Examination

Physical examination aids the accurate diagnosis of a meniscal injury in 70% of patients [24]. Gait evaluation may reveal an antalgic gait with decreased stance phase and knee extension on the symptomatic side [23]. A knee effusion is observed in about half of individuals with a known meniscal tear [25]. Quadriceps atrophy may be noted a few weeks after injury. Palpation of the joint line frequently results in tenderness. Posteromedial or lateral tenderness is most suggestive of a meniscal tear [12]. The result of a “bounce home” test may be positive. This test result is positive when pain or mechanical blocking is appreciated as the patient’s knee is passively forced into full extension [14]. The result of the McMurray test is positive 58% of the time in the presence of a tear but is also reported to be positive in 5% of normal individuals (Fig. 72.5) [13]. The Apley compression test is an insensitive indicator of meniscal injury. With this test, the prone knee is flexed to 90 degrees and an axial load is applied (Fig. 72.6). A painful response is considered a confirmatory test result with a reported sensitivity of 45% [23]. A dynamic functional test known as the Thessaly maneuver can detect a meniscal tear [26]. This maneuver is performed while the patient stands with the affected knee flexed at either 5 degrees or 20 degrees and internally or externally rotates the body. The test result is considered suggestive of a meniscal tear if there is reproduction of joint line discomfort or if clicking or locking is noted [26]. No singular meniscal provocation test has been shown to be predictive of meniscal injury compared with findings on arthroscopy. Physical examination findings become even less reliable in patients with concomitant anterior cruciate ligament deficiencies [14,27]. Neurologic examination findings, including sensation and deep tendon reflexes, should be normal unless there is associated guarding due to pain or diffuse weakness, particularly with knee extension (quadriceps muscle inhibition).

Functional Limitations

Patients with meniscal injuries may have difficulty with deep knee bending activities, such as traversing stairs, squatting, or toileting. In addition, jogging, running, and even walking may become problematic, particularly if any rotational component is involved. Laborers who repetitively squat may report mechanical locking with loss of full knee extension on rising.

Diagnostic Studies

Standing plain radiographs are usually normal in isolated meniscal injuries. Presence of osteoarthritis, as with degenerative meniscal tears, can be detected with weight-bearing anteroposterior and lateral knee films. With nondegenerative tears, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has largely replaced plain radiographic examination in detecting injury; however, meniscal tears can be present in asymptomatic individuals [12,28]. Sagittal views demonstrate the anterior and posterior horns of the menisci; coronal images can be vital in diagnosis of bucket-handle and parrot-beak tears [1,14]. There are three grades of meniscal injury as determined by the location of T2 signal intensity within the black cartilage. By definition, only grade 3 tears qualify as true meniscal tears; however, a few grade 2 lesions seen on MRI will be found to be true tears on arthroscopy (Fig. 72.7)[29]. With use of arthroscopy as the “gold standard,” the sensitivity of MRI varies from 64% to 95%, with an accuracy of 83% to 93% [16]. MRI appears to have a false-positive rate of 10% [1,24]. A 5% false-negative rate is also reported and may be due to missed tears at the meniscosynovial junction [30]. Ultrasonography has also been used to diagnose meniscal tears but with lower specificity compared with MRI [31].

Interestingly, despite the recent accessibility and advancement in ultrasonography and MRI, clinical examination by experienced physicians is cheaper and appears to be as accurate as MRI for the diagnosis of meniscal tears [29,32]. However, MRI may be particularly helpful when history and physical examination findings are equivocal and the physician is required to establish an expedient diagnosis [13,23].

Treatment

Initial

The truly locked knee resulting from a meniscal tear should be reduced within 24 hours of injury. Otherwise, acute tears of the meniscus may initially be treated with rest, ice, and compression, with weight bearing as tolerated. Patients may need to use crutches acutely. A knee splint may be applied for comfort of the patient, particularly in unstable knees with underlying ligamentous injury [22].

Analgesics such as acetaminophen or opioids can be used for pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be used for pain and inflammation.

Arthrocentesis can be performed (ideally in the first 24 to 48 hours) for both diagnostic and treatment purposes when there is a significant effusion.

Rehabilitation

Not all meniscal injuries necessitate surgical intervention or resection. In fact, some meniscal lesions have gradual resolution of symptoms during a 6-week period and may have normal function by 3 months [11]. Types of tears that may be treated with nonsurgical measures include partial-thickness longitudinal tears, small (< 5 mm) full-thickness peripheral tears, and minor inner rim or degenerative tears [33]. Healing potential is greatest for tears within the red zone [34]. In general, only meniscal injuries that are persistently symptomatic should be referred for surgical intervention.

Both nonsurgical and partial meniscectomy patients undergo similar rehabilitation protocols. Crutches may be used to off-load the affected limb. These can usually be discontinued when patients are ambulating without a limp [35]. The goal during the first week is to decrease pain and swelling while increasing range of motion and muscle strength and endurance. Institution of static strengthening in conjunction with electrical stimulation can retard quadriceps atrophy [30]. Aerobic conditioning can begin as long as the patient can tolerate bicycle training or aqua jogging. As time progresses, a combination of open and closed kinetic chain exercises in all three planes (sagittal, coronal, and transverse) can be performed in conjunction with stretching of the lower limb. Gradually, during the ensuing weeks, more functional activities are introduced. More challenging proprioceptive and balancing activities also can be started as deemed appropriate. Finally, plyometric training is begun, and the individual is gradually introduced back into sport-specific activities.

Multiple rehabilitation protocols for the surgically repaired meniscus have been described. Rehabilitation programs ideally need to be individualized to the specific type of repair performed. In addition, there has been considerable controversy among physicians about the patient’s weight-bearing and immobilization status soon after surgical repair [30,36–39]. In general, however, initial exercises are nonaggressive, avoiding dynamic shear forces that may occur from joint active range of motion. Therefore, exercises are initially static, targeting hip abductors, adductors, and extensors. Static quadriceps exercises are performed with care to avoid terminal knee extension. While superior and medial patella mobilization is begun, stretching of the lower limb musculature in multiple planes is emphasized. After 2 to 3 weeks, goals are to increase range of motion and to advance weight-bearing status while a resistance exercise program is introduced. With the absence of effusion and significant pain, improved knee range of motion from 5 to 110 degrees should be achieved. More aggressive active range of motion may be started, particularly if the repair was to the outer peripheral or vascular zone of the meniscus because the success rate for healing here is higher [30]. Gradually, more functional activities with use of resistive bands may be introduced. With time and success of the patient, resistance can be increased and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation activities can be implemented, ensuring that the individual is rehabilitated in the coronal, transverse, and sagittal planes [40].

Brace protection, if it was initially employed, may be discontinued, particularly when the patient demonstrates success with proprioceptive testing. Running, cutting, and rotational activities are avoided. However, sport-specific exercises can be initiated when no effusion exists, knee strength is at least 70% of normal, and the knee can attain full range of motion [39]. Athletes may be able to return to their individual activities at about 16 weeks for those with repairs in the vascular zone and 24 weeks for those with repairs in the nonvascular zone.

Procedures

Patients presenting after an acute injury with an effusion may benefit from a joint aspiration, not only to help relieve discomfort and stiffness but also to aid in discerning whether a hemarthrosis or marrow fat (to rule out an occult fracture) is present.

Surgery

Specific types of tears may not require surgical repair; these include longitudinal partial-thickness tears, stable full-thickness peripheral tears (< 5 mm long), and short (< 5 mm) radial tears [35]. These are usually stable and may not require either suture fixation or immobilization. However, arthroscopy may still be necessary to determine stability and to stimulate healing through perimeniscal abrasion [11].

Some larger longitudinal, radial, and degenerative meniscal tears are less likely to heal without surgical intervention. Although first-line treatment of these lesions is aggressive rehabilitation, recalcitrant cases may require a partial meniscectomy that preserves as much of the meniscus as possible [37]. In addition, the inner aspect of the cartilage, which may be ragged, may be rasped or shaved, providing a smooth surface that eliminates mechanical symptoms.

On occasion, other tears of the menisci, because of their size and location, are best treated by primary approximation with sutures and primary repair [41]. Typically, longitudinal tears longer than 5 mm in the periphery of the meniscus are best suited for this because they have a high rate of successful healing [35]. In older individuals, the mere presence of a horizontal or degenerative cleavage tear is insufficient to justify removal because these meniscal portions may still participate in significant load transmission but not necessarily cause symptoms [11]. Treatment of these degenerative tears is usually nonsurgical; however, unstable portions may be removed during arthroscopy. Good outcomes have been documented after patients with degenerative tears have been treated with aggressive rehabilitation [42].

Potential Disease Complications

Once a meniscal tear occurs, the joint inherently becomes less stable. This instability may promote further extension of the initial tear, turning a nonsurgical lesion into one in which arthroscopic repair may be necessary. Chronically, the resultant increased abnormal motion that occurs secondary to the meniscal injury may also lead to damage of the articular surface and predispose to premature osteoarthritis [12].

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that may affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. An overly aggressive regimen may lead to extension of the tear or failure of the meniscus to heal. A rehabilitative program that is too conservative, in contrast, may also lead to a significant loss of strength with muscle atrophy and decreased range of motion. If the surgical approach resulted in a significant amount of cartilage removed, the knee may be predisposed to development of osteoarthritis as originally described by Fairbank [10]. Saphenous nerve injuries as well as infections are also common complications after meniscal repair surgery and arthroscopy [12].