CHAPTER 71

Knee Bursitis

Ed Hanada, MD; Florian S. Keplinger, MD; Navneet Gupta, MD

Definition

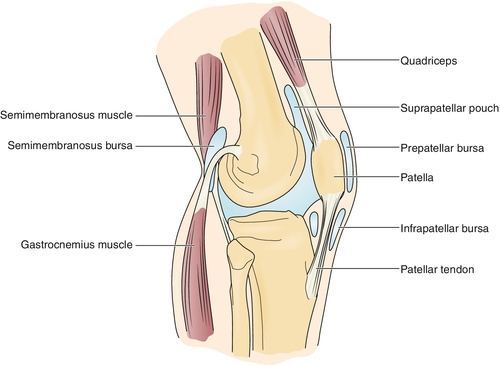

Knee bursitis is an inflammation of any bursa in the region of the knee joint and is a common clinical disorder that may lead to functional difficulties. Eleven bursae are found within this region (Fig. 71.1) [1]. Three bursae communicate with the knee joint: quadriceps or suprapatellar, popliteus, and medial gastrocnemius. Four bursae are associated with the patella: superficial and deep prepatellar, and superficial and deep infrapatellar. Two are related to the semimembranosus tendons, and two are related to the collateral ligaments of the knee (one of which is under the pes anserinus, or the conjoined tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles) [1].

In the popliteal fossa, a bursa is located between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus tendon. Swelling in this area is also called Baker cyst and may actually be due to other inflammatory or degenerative conditions (see Chapter 64). For this chapter’s purpose, discussion is limited to knee bursitis arising from inflammation of the previously mentioned bursae.

The most common knee bursitis conditions are the following.

Prepatellar bursitis (housemaid’s knee) is caused by direct trauma, such as falling on a bent knee or frequent kneeling on a hard surface [1]. A case of a massive prepatellar bursitis from chronic crawling as a means of household ambulation in an adult man with cerebral palsy has been reported [2]. In 376 subjects with knee pain and radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis, 3.1% had evidence of prepatellar bursitis on magnetic resonance imaging [3].

Infrapatellar bursitis (vicar’s knee) is usually due to repetitive knee flexion in weight bearing, such as deep knee bends, squatting, or jumping; it can be associated with patellar-quadriceps tendinitis [4,5]. In 376 subjects undergoing routine magnetic resonance imaging who had knee pain and radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis, 10.6% had evidence of superficial infrapatellar bursitis [3].

Anserine bursitis is commonly seen in overweight older women who also have osteoarthritis of the knees and in individuals who participate in sports that require running, side-to-side movement, and cutting [5,6]. In a study involving persons with a symptomatic knee presenting to an orthopedic clinic with suspected internal knee derangement who had magnetic resonance imaging, only 2.5% of these patients had radiologic evidence of pes anserine bursitis, with no gender preference [7].

Medial collateral ligament bursitis refers to inflammation of a bursa located between the deep and superficial parts of the medial collateral ligament [5]. It has been associated with degenerative disease of the medial joint compartment, with marginal osteophytic spur formation [8]. Furthermore, this bursitis may be seen in equestrian and motorcycle athletes because of the friction applied to the medial side of the knee [8].

Semimembranosus bursitis is usually seen in runners and may be associated with hamstring tendinitis [4]. This was seen in 4.4% of symptomatic subjects undergoing routine magnetic resonance imaging [3].

Symptoms

The patient will usually complain of local pain, tenderness, or swelling in the affected site. The pain is worse with flexion and usually occurs at night or after activity. The pain also may be more prominent and accompanied by stiffness on waking in the morning. Limping may or may not be present.

Physical Examination

The patient may have an antalgic gait, with a shortened stance phase on the affected side. There is discrete tenderness to palpation associated with fullness at the site of the bursa involved, and there may be associated redness and increased temperature. If the bursa connects with the knee joint, there may be an associated effusion. There is often limited range of motion in the knee. Neurologic examination findings should be normal.

Functional Limitations

The patient may have difficulty with prolonged walking. Decreased balance is often seen in older patients, sometimes necessitating assistive devices (e.g., walker, crutches, cane, or wheelchair). If there is limitation in knee range of motion, patients may have difficulty bending the knees to drive or sitting at a desk at work. They will also have problems stooping, kneeling, crawling, or climbing, which may interfere with vocational and recreational activities. Athletes such as runners may have diminished performance or may be sidelined altogether.

Diagnostic Studies

The diagnosis is based mainly on history and clinical examination. Aspiration is rarely needed but may be necessary if an infection is suspected. Radiologic studies are usually performed to rule out other diagnoses but may show exostosis in areas related to the bursa. Ultrasound imaging may be helpful to visualize the swelling in the bursal sac and may be augmented by use of an air-steroid-saline mixture as a contrast medium [9]. Plain radiographs should be obtained if a bone tumor is suspected, particularly in patients with night pain. Arthrography, which is rarely done, may show the connection to the knee joint, if it is involved. Magnetic resonance imaging may be needed to rule out a tumor or malignant neoplasm and may show a fluid collection in the involved bursa [1,4].

Treatment

Initial

Restriction of activity that provokes or aggravates symptoms is important [1,4–6,10]. In athletes, this may mean a substitution of the usual athletic activities while the healing process proceeds. Local application of ice helps decrease pain and inflammation. The patient can be taught to use superficial heat for chronic bursitis. This can be done with moistened warm compresses or with a microwaveable or electric heating pad. Precautions should be observed and given to the patient to prevent burns and other complications (see section on potential treatment complications). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be prescribed to decrease pain and inflammation. Oral steroids are generally not indicated as initial treatment.

Rehabilitation

Use of an orthosis in the affected knee may assist in preventing painful movement and further inflammation as well as provide comfort. Shoe inserts unilaterally or bilaterally, depending on the pathologic process, may also lead to positively altered biomechanics of the lower extremities to improve symptoms. For example, for those individuals with associated medial compartment knee osteoarthritis, a lateral wedge insole may improve symptoms and function [11].

Formal physical therapy may address stretching of the quadriceps, hamstrings, iliotibial band, and hip adductor muscles if these muscles are tight. Strengthening exercises are often needed in chronic knee bursitis because of disuse weakness. Correction of gait abnormalities (e.g., leg length discrepancy with a heel lift, or pes planus with orthotic inserts) is also important. Patients should also be counseled to protect their knees from further trauma (e.g., by avoidance of bending or kneeling or by use of knee pads).

Modalities such as ultrasound have not been proved to be more effective than a combination of the aforementioned measures. Ultrasound should be avoided when an effusion is present because it can worsen the effusion. Phonophoresis and iontophoresis may have merit, but they are still controversial [12].

Procedures

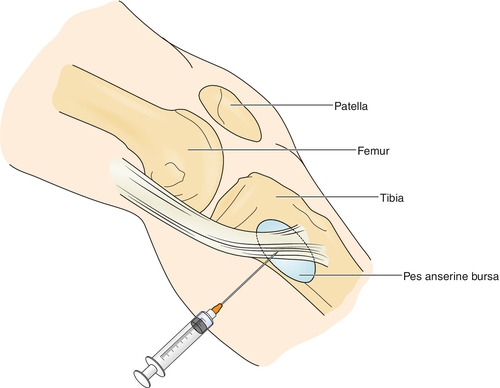

Intrabursal corticosteroid injection is appropriate if there is no response to conservative management or if the patient demonstrates significant functional limitations (Fig. 71.2). Typically, no more than three injections are done in a 6- to 12-month period. Alternative diagnoses should be considered for patients with refractory symptoms.

The patient is generally advised to avoid activity involving the area injected for approximately 2 weeks to promote retention of the corticosteroid in the bursa and to avoid systemic absorption [13]. There is some evidence to suggest that persons who have pes anserine bursitis that is demonstrated with ultrasonography may have the best outcome after corticosteroid injection [14,15].

With use of a high-frequency linear ultrasound transducer along the medial aspect of the knee, a mixture of anesthetic and long-acting corticosteroid may be injected through a 25-gauge needle [16]. However, a study demonstrated that there is no additional benefit after an injection with methylprednisolone [17].

As an alternative to surgery, in cases of persistent prepatellar bursitis, chemical ablation has been used, although no robust clinical trials exist to provide evidence for its efficacy [18].

Surgery

Surgery is generally not indicated and should be undertaken only in refractory cases. Excision of a bursa can be considered if the disease does not respond to conservative measures, despite treatment, and it greatly limits the patient’s activities. Successful surgical resection of bursae has been reported in the literature [19–22]. Outpatient endoscopic bursectomy under local anesthesia has been reported in a case series as an effective treatment of post-traumatic prepatellar bursitis after failed conservative management [23].

Potential Disease Complications

Possible complications include chronic pain, deconditioning, disuse muscle atrophy, and knee flexion contracture. Furthermore, this may lead to decreased walking ability and postural instability over time, especially in older adults.

Potential Treatment Complications

Potential complications from medications include drug hypersensitivity and prolonged bleeding; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have gastric, renal, and hepatic side effects. Hyperglycemia, electrolyte imbalance, and gastric irritation or ulceration from intrabursal steroid injection are not as common as with orally administered corticosteroids but can still occur from systemic absorption of the injectant. Local ice application may produce hypersensitivity and vasoconstriction in patients with Raynaud disease and peripheral vascular disease, and local heat application may produce burns, sedation, skin discoloration, and vascular compromise. Moreover, injections may result in drug hypersensitivity, sterile abscess, infection, nerve injury, tendon rupture, and lipoatrophy from intralesional steroids [13,14]. Furthermore, a case of patella tendon rupture has been reported after arthroscopic resection of the prepatellar bursa [24].