to the directions set by the government of the day’, but beyond that, it should be ‘innovative and imaginative’. The manner of giving advice should be ‘robust’, as secretaries must ensure that the minister is aware of all relevant facts about a policy and its likely impact, even if unfavourable, and of any difficulties, practical or political, it might present to officers implementing it (Shergold 2003 p 49). From this position the public service has been able to exert considerable influence over policy making. A health researcher found that bureaucrats were one of the policy ‘actors’ cited most frequently as influencing health policy, though less influential than the medical profession (Lewis 2005).

For years this tradition of giving ‘robust’ advice was underpinned by secure tenure for senior bureaucrats, making them relatively independent of political pressure. Secretaries, or heads of departments, the legendary ‘mandarins’, presided in the past over a ‘bureaucratic edifice’ which was the ‘permanent repository of wisdom on which its political masters of all colours could rely for frank and fearless advice’ (MacCallum 2004 p 28). For some, this tradition of ‘speaking truth to power’ remains the essence of the Westminster system, ‘the crucial element in advanced and rational governance …’ (Hennessy 1997 p 2).

Secretaries today are unlikely to address a prime minister with, ‘Now listen here …’ as one did in the 1960s (Weller 2001 p 90), but they are still obliged to make sure that a minister has all the facts, unwelcome or not. Advice should be politically non-partisan, but not politically naive, which demands a trusting and balanced relationship between ministers and secretaries, with the latter skilled at providing the evidence-based information essential for policy. Public service loyalty requires pointing out to a minister the potential unpopularity or adverse effects for the government of a particular policy (Walter 2006).

The public service is thus expected to be responsive to ministers’ wishes, whether officials agree with them or not: the ‘traditional public servant’ deals in a non-partisan way with both political parties (Grattan 2005). Any public service inclination towards independence is therefore constrained by the duty to follow, to respond actively to ministers’ directions, provided always that they are legal.

PUBLIC SERVANTS AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST

Ministers thus exercise, at least in theory, political control over their public servants, who are in turn accountable to them for departmental activities, reflecting secretaries’ further, sometimes overlooked, task as managers of often large public organisations. Political control is not, however, without its critics. Given the long tradition of public service professionalism, its requisite ability to serve all governments impartially, if public servants consider ministers, or their staff, are doing something questionable, perhaps they should go beyond immediate political authority to serve the ‘public interest’ through speaking out.

As citizens we expect public servants to put our interest before theirs when exercising their powers. The public service is not, after all, like the Australian Medical Association (AMA), which, however often its officers cite their devotion to the welfare of all citizens, is there in the end to defend and promote the sectional interests of medical practitioners. Rather, bureaucrats are ‘guardians of the public interest in protecting constitutional processes’, but have no authority to act as ‘superior arbiters’ in policy decisions – politicians define the public interest, and face electors’ judgment for doing so (Mulgan 2000 p 3).

SIZE AND STRUCTURE OF THE AUSTRALIAN PUBLIC SERVICE

Whether at federal, state or territory level, structure reflects the division of powers under the Australian Constitution, and in turn the priorities of the incumbent government. In the Australian public service (APS), departments embody primary functions, such as financial management, defence, immigration, welfare, health and education. There are the ‘central’ departments of Treasury, Finance and Administration, and Prime Minister and Cabinet, which tend to be more powerful than the ‘service’ or ‘spending’ departments, such as Health or Education. Some of these responsibilities appear also in the apparatus of state governments, especially health and education. Each APS department has a hierarchy, from secretaries down through the senior executive service and various classifications below, including training and graduate entry positions (Singleton et al. 2006).

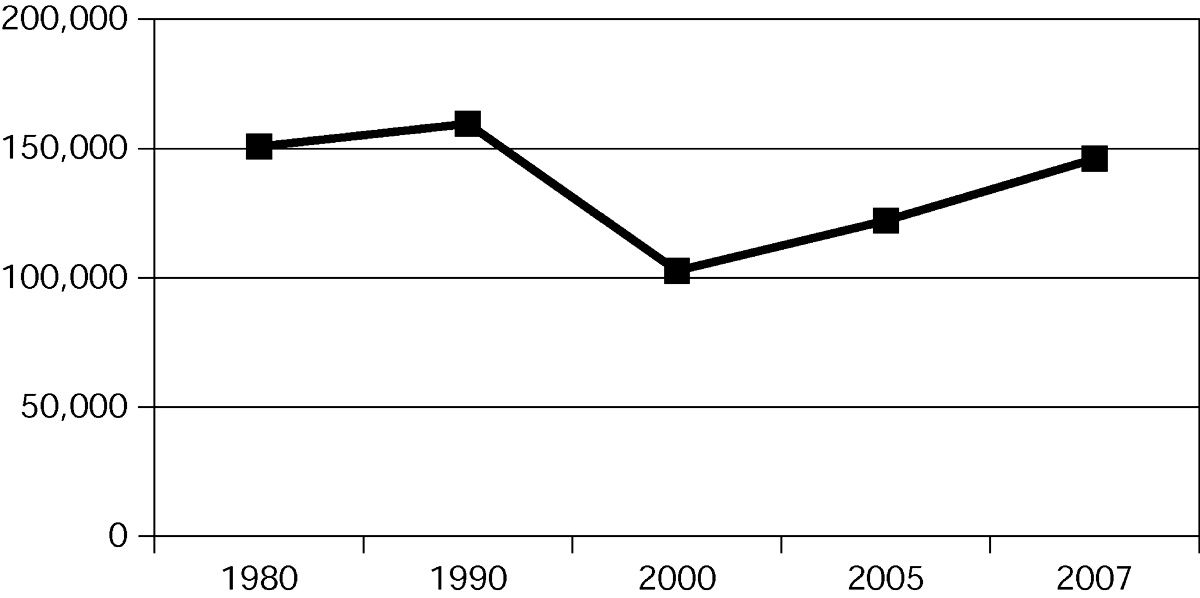

The actual number of APS public servants depends on their being classified as staff under the Public Service Act 1999, as distinct from those outside the APS, but still in the public sector. Figure 7.1 shows the overall decline in APS numbers since 1980 and the recent rise to 146,000, with 5000 Medicare employees now included, and as a result of extra security measures (Trembath 2006). The APS is divided into 18 departments, or ministerial portfolios (see government website for details). Government functions, however, cannot be divided neatly into separate compartments: every significant policy issue crosses structural demarcations. Yet to the public, all services ‘must look like seamless delivery’ (Shergold 2003 p 50), so coordinating devices are essential, such as formal or ad hoc interdepartmental committees or less formal meetings between officials.

Figure 7.1 Size of the Australian public service Sources: Singleton et al. 2006 p 241; Trembath 2006

The Department of Health and Ageing has nine sector divisions, including the Medical Benefits and Pharmaceutical Benefits divisions, four cross-portfolio divisions, and eight state and territory offices. The department also has responsibility for 56 agencies, which vary from those central to its work, such as Medibank Private and the National Health and Medical Research Council, to others which seem peripheral, such as the National Public Toilet Map.

After the 2004 election, the government created a Department of Human Services within the Department of Finance, to show the government’s commitment to oversee and improve the delivery of ‘important government services’. It brings together six agencies, including Medicare Australia (the former Health Insurance Commission) and Commonwealth Rehabilitation Services (Kerr 2005b), which both might seem more suitably housed in the health department.

Many of the 56 non-departmental organisations are statutory agencies with varying degrees of independence from ministerial (i.e. political) control – an example is the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), a government statutory authority within the department, but with some autonomy in carrying out its statutory obligations. Australian governments have long considered freedom from political interference desirable for public bodies such as the AIHW, with research and educational functions, or for regulatory bodies like the Aged Care Standards and Accreditation Agency. A different example is Medibank Private, a non-departmental organisation which is actually a government business enterprise (Singleton et al. 2006), a threatened species as a result of the privatisation of many such agencies.

State and territory health departments tend to look different, reflecting their more direct part in healthcare provision, especially acute hospital care. Queensland Health, for example, has six ‘portfolio’ type divisions, including a ‘Reform and Development’ division as a response to the recent inquiry into Queensland public hospitals (see Ch 15), while the state as a whole, like New South Wales, is divided into similar regionally based area health services. These arrangements illustrate the difficulty of organising a complex system like healthcare, in that governments need nation- or state-wide, as well as area-based, services.

PUBLIC SERVICE REFORM

Since the relatively stable period of the ‘old’ APS up to the 1970s, the bureaucracy has undergone considerable change. As Kingdon (1984 p 115) says, a condition becomes a problem when we decide to do something about it and the ‘problem’ in this case was perceived as the powerful position of secretaries, whom some ministers in the 1970s considered too dominant and not sufficiently responsive to politicians’ wishes. By the 1980s, a new Labor government was determined to make the APS more responsive to ministers and to the public (Weller 2001). Changes under the 1984 Reform Act made it easier for staff to enter from outside, rather than rising from the lower levels, and allowed for the removal of secretaries. Major aims included improving responsiveness, reducing the cost of government operations (through attention to results and cost effectiveness), enhancing delegation and devolution of authority, and aiming at more efficiency and flexibility, with a more commercial approach (Holmes & Wileman 1997 p 14). The APS, lagging behind other countries in the early 1980s, made considerable reform progress in the next decade, reforms extended and deepened under the Howard (Coalition) government and consolidated in the Public Service Act (Halligan 2005b).

The idea of a career public service, with its tenured ‘mandarins’ at the top as the sole source of ministerial advice and information, has been transformed. Secretaries moved to contract appointment from 1994, compensated by higher pay (Weller 2001). Former central control of budgets by Treasury, and of employment and working conditions under the Public Service Board (abolished 1987) vanished, these functions delegated to departments, whose senior officials now managed staffing and budgets.

External reasons added to the drive for change, especially financial constraints, and awareness of similar changes occurring in Britain and the US. A department head saw the pressure for change coming from, first, rising public expectations for more varied, complex and better quality services (with lower taxes); and second, globalisation and new technology affecting Australia’s ability to compete in world markets (Hawke 2002). All helped gain acceptance for the shift towards what became known as ‘new public management’ (NPM) or ‘managerialism’, based on three central tenets:

‘Privatisation’ accompanied NPM – not just government selling public assets such as Telstra, but also the private sector replacing government in publicly funded service provision (‘outsourcing’), or government withdrawing from such provision (Aulich 2005 pp 58–9).

NPM also implied the public sector adopting private sector methods of management, including market mechanisms and some competitive practices. Agencies now emphasised results, or ‘output’ and ‘outcomes’, over bureaucratic rule-dictated processes, and used ‘explicit standards and measures of performance’ (Zifcak 1997 p 107; Singleton et al. 2006). The 1999 reforms added the premise that the APS would ‘benchmark’ its performance against private sector ‘best practice’, improve financial management, and use such arrangements as performance indicators, competitive tendering and contracting out ‘to improve accountability, quality and cost-effectiveness’. The Act also included for the first time a statement of values and a code of conduct, including extra protection for ‘whistleblowers’ (Singleton et al. 2006 pp 241–3, 254).

By the mid-1990s, the operative government model viewed the public sector as an adjunct to the private, and depicted the public service as less influential than, and subservient to, the private sector. The Howard Government, convinced of private sector pre-eminence, achieved an ‘overall repositioning’ of the public sector, in line with its vision of the public service as a business, operating in circumstances of competition and judged by results (Halligan 2005a, b). The public service, a secretary considered, must be ‘efficient and flexible’, with staff able to move around without the old prescriptive rules and detailed regulations (Moore-Wilton 2000).

The effects of reform

As Halligan (2005b) notes, these major reforms have:

2. changed the boundaries between public and private sectors

3. altered the internal structure of the public service through extensive devolution.

Predictably, the effects have been mixed, receiving both commendation and criticism. An immediate consequence of reform has been a smaller public sector, owing to reduced functions (with some contracted out) and efficiency improvements. It might be difficult to establish whether or not this ‘radical reconstruction’ of the public sector has made it more efficient but its shrunken size allowed a considerable saving of public funds (Aulich 2005 p 73). One view is that at least some of the changes over the past 20 years have led to improved service delivery (Prasser 2004), and a senior bureaucrat thinks that concentrating on outcomes over process has produced impressive gains, including improved performance (McCann 2001). Yet Palmer (2005) criticised staff of the Department of Immigration precisely for being excessively concerned with processes and quantitative yardsticks, to the detriment of quality results and humane treatment of clients. Bradley and Parker (2006) found that Queensland public sector staff perceived their organisational culture to be similar to that of the traditional bureaucracy, though they would have preferred a more ‘human relations’ approach.

NPM policies have also influenced healthcare agencies in Australia and elsewhere, as a consequence of rising demand for health services and limited budgets. Allied health researchers showed that corporate entrepreneurial approaches can develop in public sector conditions: a group of allied health staff, many with business qualifications, saw themselves as ‘in the business of allied health service delivery’, in an ‘integrated delivery system’, in which the professions were no longer competing with each other for a shrinking budget. Given the present ‘turbulent’ healthcare environment, these researchers advocate organising in this way to maximise entrepreneurship and innovation (Rowe et al. 2004 pp 25, 28).

Effects of reform 1: political–bureaucratic relations

The relationship between minister and departmental secretary is central to the integrity of public service operations, and it is vital to have a solid, cooperative association, a ‘partnership’, with the minister trusting the secretary’s judgment and ability – difficult to establish within the present 5-year period, so some relationships are likely to be fraught (Weller 2001). A current debate is whether the public service has become ‘politicised’, especially given the aim of making it more responsive. A senior journalist asserts that it has: the Prime Minister, he alleges, has ‘brought to its zenith’ the shift of power from the public service to ministers, under a conviction that the service is there primarily to help government realise its aspirations (Kelly 2006 p 11).

The 1999 Public Service Act underlines the more precarious position of secretaries; the prime minister can terminate the appointment of a secretary at any time without having to give clear reasons. Some unjustified sackings have probably occurred. On its accession to power in 1996, the Howard Government dismissed one-third of 18 departmental secretaries, including the secretary of the Department of Health, in a ‘bloodbath’ of ‘unprecedented’ dimensions (MacCallum 2004 p 28). At about the same time even more draconian sackings occurred in Queensland and New South Wales under Labor governments (Prasser 1997). APS colleagues worried that some of the terminations were ‘capricious’, with detrimental implications for the capacity to provide truthful advice (Keating 2003 p 96). Others regretted the loss of experienced staff and ‘institutional memory’, and deplored the possibility of a minister who was ‘an absolute dill coming in and chucking out a competent bureaucrat for no good reason’ (Weller 2001 pp 106, 108).

Under these conditions, senior officials could hesitate to give ministers unwelcome news or opinions (Weller 2001), though an incumbent secretary believes it is still possible to respond actively to a policy direction while offering dispassionate advice (Williams 1998). In Britain public servants were criticised as being too accommodating to ministers’ wishes, even failing to warn when a policy went against government interests (Barker & Wilson 1997). Another view is that the independence and expert advice of the bureaucracy are often ‘squandered’ in favour of responsiveness – of giving the government the decisions and processes it wants (Prasser 2004 p 94).

Excessive responsiveness or ‘politicisation’ has risks: one critic believes that ‘supine’ leadership in the Department of Defence allowed the ‘children overboard’ story to remain uncorrected before the 2001 election – responsiveness in that case meant ‘not inconveniencing the minister with facts’ (McKernan 2002 p 6). Similarly, the Palmer and Comrie reports on the Department of Immigration found that public servants acted unlawfully and irresponsibly in their dealings with individual clients; the department was infected with a ‘defensive and dehumanised’ cultural mindset; and there was a pervasive failure of departmental leadership. Perhaps some senior officials are now too anxious to shield ministers from political embarrassment, thus failing to fulfil their legal and administrative responsibility to the public (Kelly 2006 p 12, Prasser 2004).

A former department head reasserts the traditional view that secretaries are responsible for ensuring ministers receive the advice they need to hear, not just what they might want to hear (Keating 2003), since those responsible for managing a policy or program must also be accountable to a designated authority for their performance. Public accountability means control over the conduct of services funded through public money. Both responsibility and its complement, accountability, should be balanced with responsiveness, with a further balance between responsiveness to authority (department and government) and to clients (Uhr 1999). In the Immigration case it appears that departmental staff concentrated on responsiveness to authority, while neglecting the welfare of clients; less likely to occur in a service like health, where staff feel some accountability to patients.

A corollary of over-responsiveness to authority is public servants leaving themselves open to blame. Exposure of child abuse in Queensland showed how governments are quick to blame the public service and hide behind ‘the old subterfuge, “why weren’t we told?” ’ (Prasser 2004 p 100). In Britain too, bureaucrats are increasingly ‘named and blamed in public’, so ministers can then deny responsibility for their departments’ operational errors (Polidano 2000 p 177).

Political control of the bureaucracy, with concomitant decline of public service independence and influence, has been augmented by rising numbers of ministerial staff advisers, or ‘minders’, now at their highest ever numbers, whose promotion depends on protecting and advancing their minister’s interests. Although there are examples of good relations between advisers and bureaucrats, there is evidence of difficulties, and a need to clarify responsibilities (Halligan & Adams 2004). Further, many advisers have acted at times without the ‘skill, discretion and integrity’ the 1984 regulating Act expects of them (Walter 2006 p 24).

Some members of a Senate committee considered that, like bureaucrats, advisers should be publicly answerable to parliament (Forshaw 2003). Otherwise they appear to fall into an accountability vacuum and tend to obscure the transparent operation of government responsibility, especially as secretaries are now less able to insist on control over departmental advice, ensuring it reaches the minister (Keating 2003; Walter 2006).

Although the public service still accounts for the bulk of policy advice, many more sources of advice are now on offer, including advice from ministerial staff. Judging which, if any, of these sources are offering sound policy advice based on research can be problematic, and certain public interests can be overlooked – research critical of the private health insurance rebate, for example, is unlikely to influence health policy (Kelly 2006). The cost of the rebate is not defined as a ‘problem’ by a government ideologically convinced of private sector superiority (Kingdon 1984).

As many public service decisions are discretionary, additional means of enforcing accountability are necessary. These include departmental performance indicators and annual reports and the Auditor-General’s annual report on departmental activities. Citizens seeking redress of grievances have recourse to MPs and parliamentary committees, administrative review, the Ombudsman, and freedom of information (FOI).

Administrative review tribunals have extended their reach recently; for example, refusing to uphold the deportation of certain aliens (Singleton et al. 2006). This expansion of administrative law has improved government decision making: decision makers ‘know there is an unseen presence’ observing them, thus are more likely to be careful, aware that decisions may have to be justified (McMillan 2002 p 43). Even so, the operation of ‘spin’ now seriously restricts ‘our knowledge of how decisions are made … as governments muzzle public servants and funnel information through increasingly elaborate PR systems’ (Grattan 2006).

The Ombudsman can pursue a wider range of items than legal tribunals, but is limited to recommending decisions for review (Singleton et al. 2006). In his 2005–06 report he noted the difficulty of applying complex legislation to thousands of clients, with staff often slow to adapt to unexpected issues, and people ‘falling through the cracks’ of programs. FOI legislation also helps counter bureaucratic secrecy: the Act extends citizens’ legal right to have some access to government documents, promoting accountability. The Ombudsman, however, found ‘an uneven culture of support’ for FOI among agencies, with unreasonable delays in processing some requests (Commonwealth Ombudsman 2006 pp 100, 112, 116).

Effects of reform 2: privatisation and outsourcing

Observers agree that many reforms have run their course, though some of the reform agenda continues, such as emulating the private sector. Few public sector agencies are without their business plans and project teams – in spite of the 2003 report of the Royal Commission into HIH Insurance which revealed a large private sector corporation with seriously incompetent management, poor governance practices, and frequent disregard of the law (Prasser 2004). In healthcare, Australia’s public–private mix of provision is not necessarily ideal: the private sector has an incentive to avoid high-volume users of expensive care, leaving these patients to the public sector. Further, competition is not always suitable for healthcare, and rampant entrepreneurialism can produce ‘dysfunctional outcomes’, affecting ‘cost, access and quality’ (Deber 2005 p 388).

A former secretary argues that, even if declining in popularity, managerialism has engendered a performance culture. Mistakes include an ideological assumption that the private sector always delivers services more efficiently than the public, and new criteria are necessary to decide when to use either. Over-rigid contracts regulating relations between government/purchaser and private organisations/providers have also caused difficulties (McCann 2001).

The previous dedication to outsourcing has also been waning and there may even be a reassessment of the value of the public sector, owing in part to the difficulties of establishing accountability under privatisation and outsourcing (Halligan 2005a). Alternative service providers pose a challenge with claims of lowered accountability on the grounds that information about their performance is ‘commercial-in-confidence’ (Uhr 1999 p 100). Indeed an aim of outsourcing government functions to the private sector might be removing them from public sector accountability (McMillan 2002).

After the failure of a large and complex project to outsource information technology to the private sector, the government switched to decentralised IT, leaving it to individual department and agency heads (Aulich & Hein 2005). Yet in healthcare, a controversial outsourcing overseas of blood plasma fractionation was proposed, under the Australia–US Free Trade Agreement. A report to the Minister for Health in December 2006 rejected this, arguing that it was ‘not an advantageous option’. The minister disagreed, proposing future arrangements through tender, though depending on state health ministers’ agreement (Australian Red Cross Blood Service [ARCBS] 2006).

A further criticism of NPM relates to performance indicators. In healthcare, measurements of performance have low predictive value in detecting poor-performing hospitals (Scott & Ward 2006). In the UK, much performance data is described as ‘data rich and information poor’, with some hospitals achieving good performance ratings for no more than balanced budgets and clean premises (Aulich 2003). Queensland Health (2005) reported that administrators in some hospitals, influenced by officials in the state health department, saw themselves as running a business with fixed budgets, within a culture of economic rationalism. A Canadian expert agrees with the ‘low measurability’ of much hospital care, adding that ‘health care does not have the production characteristics to enable an efficient market in the absence of regulation’ (Deber 2005 p 390).

A Tasmanian hospital adopted a social market model in preference to competition and market forces, believing it more suitable for a workplace where staff are ‘at once highly trained and difficult to replace’ and where services are difficult to price or judge easily for quality. This was a partnership arrangement, with a focus on reciprocity and collaboration, on staff networks and teams, but with some NPM practices such as ‘benchmarking’ (Adams & Hess 2000 p 52).

Effects of reform 3: the structure of the public service

A lesson learned from the IT outsourcing failure was that coordination across the public service was weak (Aulich & Hein 2005) – the previous policy of devolving management functions to departments had benefits, but one result was a ‘disaggregated’ service (Halligan & Adams 2004 p 85). Improving security in the ‘war on terror’ demanded better coordination across the highly devolved structure, compelling the government to respond with a renewed emphasis on horizontal over vertical structures. Unlike the US decision, there was no creation of an overarching security department, but rather adoption of a ‘whole-of-government’ approach across the APS, giving more prominence to the central agencies and encouraging public servants to develop a cooperative culture. Inevitably this has led to growth in the size and cost of the public service (Halligan & Adams 2004). Similarly, where accountability has become nebulous through outsourcing to private agencies, horizontal devices such as networks, partnerships and alliances are necessary (Considine 2003).

In healthcare NPM has brought innovations such as evidence-based medicine and nursing, case-mix funding, and patients ‘restructured’ into clients or consumers. The workplace for some medical practitioners, nurses and allied health staff has been reorganised into devolved units, a model of unit dispersal that allows for more ‘patient-focused’ care, though not so far a widely adopted method of organising (Rowe et al. 2004). There is current interest, however, in developing a more integrated health system, with integrated care approaches to ensure more appropriate and cost-effective care (Podger 2000), but this will be difficult, given that competitive models in healthcare are often incompatible with cooperative and integrated services (Braithwaite 1997; Deber 2005).

LOOKING AHEAD

The public service has experienced considerable change over the past 25–30 years under the influence of ‘managerialism’, as has healthcare. Critics are now suggesting modification of the present emphasis on private sector ideas and practices, and a reconsideration of some of the benefits of public provision, such as equitable access for citizens, and a clear line of accountability to a responsible authority. Importing private sector practices or shifting services and costs to the private sector is not the only solution to the ‘problem’ of paying for healthcare (Kingdon 1984). The ethos of healthcare requires services based above all on need, rather than ability to pay, on achieving the best results for patients, rather than profits for investors (Deber 2005). The APS is now moving more towards increased emphasis on coordination and cooperation, and in healthcare, where competition can divide providers, fragment services, and limit equitable access for patients, high-quality care requires a renewed focus on integration and cooperation between services.