CHAPTER 67

Compartment Syndrome of the Leg

Joseph E. Herrera, DO; Mahmud M. Ibrahim, MD

Definition

Compartment syndrome can be either an acute or chronic condition caused by increased tissue pressure within an enclosed fascial space. The focus of this chapter is compartment syndrome of the leg, although it can also affect the thighs or upper extremities.

Acute Compartment Syndrome

Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) is a serious condition caused by a rapid rise in pressure in an enclosed space, which can lead to necrosis of the muscles and nerves in the involved compartment. Untreated, ACS can progress to contractures, paralysis, infection, and gangrene in the limb as well as systemic problems, such as myoglobinuria and kidney failure [1]. ACS, most commonly occurring in males younger than 35 years, is most often caused by trauma such as fractures, crush injuries, muscle rupture, direct blow to a muscle, and circumferential burns. Direct pressure from a cast or antishock garment can increase the risk for compartment syndrome [2]. ACS can occur in as many as 17% of tibial fractures [3]. The anterior compartment is most commonly affected, although multiple compartments are often involved.

Nontraumatic causes of ACS are more rare. These include hemorrhage into a compartment, as can occur in anticoagulated patients [2], and compartment syndrome after diabetic muscle infarction [4]. In patients with decreased mental status with prolonged limb compression, such as with alcohol or drug abuse, ACS can also develop from soft tissue injury and swelling [5].

Another nontraumatic cause of compartment syndrome is ischemia and then hyperperfusion caused by prolonged surgery in the lithotomy position. This is also known as well leg compartment syndrome and is most often seen after pelvic and perineal surgery. Risk factors include the length of the procedure, the amount of leg elevation, the amount of perioperative blood loss, and the presence of peripheral vascular disease and obesity. The overall incidence in complex pelvic surgeries may be as high as 1 in 500 [6].

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

Chronic compartment syndrome (CCS) occurs when the fascia in the lower leg does not accommodate to the increase in blood flow and fluid shifts that may occur with heavy exercise [7]. An increase in compartmental pressure then interferes with blood flow, leading to ischemia and pain when the metabolic demands cannot be met [8]. The risk of CCS is increased by anabolic steroids, which can induce muscle hypertrophy, thereby causing an increase in intracompartmental pressure and decreasing fascial elasticity [9]. CCS is most commonly seen in runners [10], cyclists, and other athletes in sports that demand running, jumping, and cutting, such as basketball and soccer. The true incidence is unknown as most people suffering from early symptoms will decrease or modify their activity [11]. With normal physical activity, muscle volume can increase up to 20% [12]. The anterior compartment is most commonly involved, followed by the deep posterior compartment [11].

Symptoms

The area in which symptoms occur and the type of complaints depend on which compartment is involved.

Acute Compartment Syndrome

Patients may present with pain out of proportion to the injury and swelling or tenseness in the area. Other symptoms include severe pain with passive movement of the muscles within the compartment, loss of voluntary movement of the muscles involved, and sensory changes and paresthesias in the area supplied by the nerve involved [3,7]. The classic findings associated with arterial insufficiency are often described as signs of ACS, but this is incorrect. Of the five classic signs (pain, pallor, pulselessness, paresthesias, paralysis), only pain is commonly associated with compartment syndrome, particularly in its early stages [12].

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

In CCS, pain has a gradual onset that usually coincides with an increase in exercise training load or training on hard surfaces. It is described as aching, burning, or cramping and occurs with repetitive movements in a specific muscle region. The pain usually occurs around the same time each time the patient participates in the activity (e.g., after 15 minutes of running) and increases or stays constant if the activity continues. The pain disappears or dramatically lessens after a few minutes of rest. Symptoms can occur bilaterally [8].

As symptoms progress, a dull aching pain may persist. Pain may be localized to a particular compartment, although multiple compartments can often be involved. Numbness and tingling may occur in the nerves that travel within the involved lower limb compartment. CCS can be seen with other overuse syndromes (e.g., concurrent with tibial stress fractures).

Physical Examination

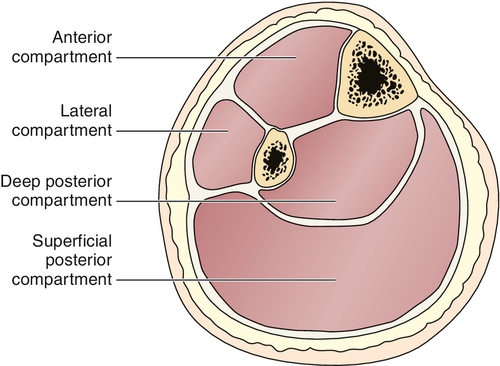

The examination is focused on the following four compartments of the leg (Fig. 67.1).

Anterior compartment contains the tibialis anterior, which dorsiflexes the ankle; the long toe extensors, which dorsiflex the toes; the anterior tibial artery; and the deep peroneal nerve, which supplies sensation to the first web space.

Lateral compartment contains the peroneus longus and brevis, which evert the foot, and the superficial peroneal nerve, which supplies sensation to the dorsum of the foot.

Superficial posterior compartment contains the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, which plantar flex the foot, and part of the sural nerve, which supplies sensation to the lateral foot and distal calf [1,8,12].

Deep posterior compartment contains the tibialis posterior, which plantar flexes and inverts the foot; the long toe flexors, which plantar flex the toes; the peroneal artery; and the tibial nerve, which supplies sensation to the plantar surface of the foot. This compartment may contain several subcompartments [13].

Acute Compartment Syndrome

In ACS, inspection reveals a swollen, tense limb. Motor testing reveals weakness or paralysis of the muscles involved in the affected compartment. Sensory testing may show numbness in the area supplied by the nerve involved in the affected compartment. Two-point discrimination is a better diagnostic test for compartment syndrome than pinprick [13]. Pulses and capillary refills are generally normal as these are involved only with extremely high pressures [3,7,14,15].

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

In CCS, inspection is usually unremarkable, but fascial defects have been observed in up to 40% of individuals. These defects may represent the body’s attempt to accomplish an autorelease [11]. Palpation of the affected area will reveal a firm compartment and tender muscle group. There may also be tenderness along the posteromedial surface of the tibia [16]. In approximately 40% of cases, muscle herniation in the compartment can be palpated, especially in the anterior and lateral compartments where the superficial peroneal nerve pierces the fascia [6]. In severe cases, sensory testing will show numbness in the area supplied by the nerve involved, but this is usually normal at rest [7]. Motor testing may reveal weakness, depending on the compartment involved: dorsiflexion weakness if the anterior compartment is involved, foot eversion weakness if the lateral compartment is involved, and plantar flexion weakness if one of the posterior compartments is involved. Pain is reproduced by repetitive activity, such as toe raises, or running in place. Compartment syndrome occurs more commonly in patients who pronate during running; thus, pronation is a common finding on physical examination [1,7,17].

Functional Limitations

Acute Compartment Syndrome

The sequelae of ACS may be nerve and muscle injury with resulting footdrop, severe muscle weakness, and contractures. This can lead to an abnormal gait and all the limitations that this can cause, including difficulties with stairs, sports participation, and activities of daily living. In addition, it can lead to muscle necrosis, thereby causing long-term disability [18].

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

With CCS, functional limitations usually occur around the same point each time during exercise, at that individual’s ischemic threshold. For example, symptoms may start to develop each time a runner reaches the half-mile mark or each time a cyclist climbs a large hill. This may significantly limit sports participation and occasionally even interferes with activities of daily living, such as prolonged walking.

Diagnostic Studies

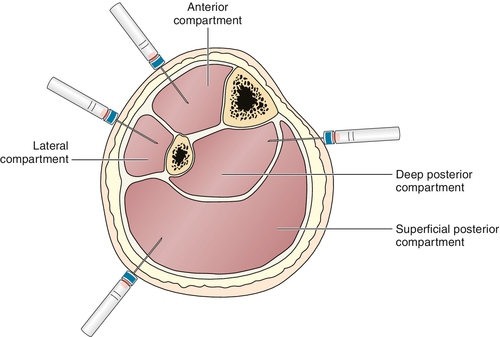

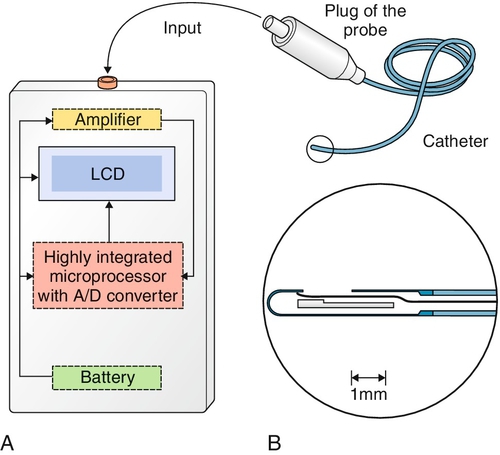

Compartmental tissue pressure measurement is the “gold standard” for diagnosis. The devices most commonly used to measure intracompartmental pressures were traditionally the slit and wick catheters (Fig. 67.2) [7]. Newer devices, such as the transducer-tipped probe (Fig. 67.3), are now gaining popularity [19]. Ultrasound-guided transducer placement is especially helpful in patients receiving anticoagulation, patients with a large body habitus, and patients with distorted anatomy, such as after surgery or trauma [11].

Acute Compartment Syndrome

Normal compartment pressure is less than 10 mm Hg. Traditionally, absolute tissue pressure above 30 mm Hg was considered the cutoff value for fasciotomy to be performed [7,19]. However, it is likely that many unnecessary fasciotomies were performed by use of this measure alone. Currently, continuous monitoring of compartment pressures is used in high-risk cases, such as leg trauma with tibial fractures. The differential pressure, calculated as the intramuscular pressure subtracted from the diastolic blood pressure, determines the treatment course. If the differential pressure is less than 30 mm Hg, fasciotomy is indicated [20]. Studies have shown that if this differential pressure remains consistently above 30 mm Hg, even with markedly elevated tissue pressures, patients have excellent clinical outcomes and fasciotomy is not necessary [20,21].

Because of the invasive nature of compartmental pressure measurements, other diagnostic tools have been sought. Magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in making the diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging findings may include loss of normal muscle architecture on T1-weighted images, edema within the compartment, and strong enhancement of the affected compartment with the contrast agent gadolinium-DTPA [22].

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

For CCS, absolute pressure measurements obtained at rest, during exercise, and after exercise are used to make the diagnosis. Interestingly, there does not seem to be a particular threshold compartmental pressure at which symptoms occur, and patients with higher pressures do not necessarily have worse symptoms than those of patients with less abnormal pressures [23]. The average time from the onset of symptoms to the time that the diagnosis is made is 22 months [7].

The following is one set of values [7,15] commonly used to diagnose anterior compartment syndrome:

• Pre-exercise pressure > 15 mm Hg

• 1 minute after exercise > 30 mm Hg

• 5 minutes after exercise > 20 mm Hg

It is important that the patient’s symptoms correlate with the compartment in which there is elevated pressure. Pressure should increase in the symptomatic compartment with exercise and remain elevated for an abnormal time [8,23]. Values for posterior compartments are more controversial. Normal resting pressures are less than 10 mm Hg, and values should return to resting levels after 1 to 2 minutes of exercise [15].

Drawbacks to measurement of pressures include the following:

• They are invasive and can be complicated by bleeding or infection.

• Because of the anatomy, it is difficult to test the deep posterior compartment.

• Pressures are dependent on the position of the leg and the technique used, so strict standards should be followed.

• It is time-consuming because each compartment must be tested separately, and all compartments should be tested because multiple areas are often involved.

• It is often difficult for patients to exercise with the catheter in place [17,24].

Because of these drawbacks, alternative tests to confirm the diagnosis are sometimes used. Magnetic resonance imaging done before and after exercise can show increased signal intensity throughout the affected compartment in the T2-weighted images after exercise in patients with compartment syndrome [25,26]. Alternatively, near-infrared spectroscopy has been used as well. This method measures the hemoglobin saturation of tissues [9]. In cases of CCS, there is deoxygenation of muscle during exercise and delayed reoxygenation after exercise. Failure of the compartment to return to baseline within 25 minutes after exercise is diagnostic of CCS [11]. Although near-infrared spectroscopy seems to be helpful in patients with anterior compartment syndrome, light absorption may be altered in deeper compartments, and therefore it is more difficult to monitor the pressure in these deeper compartments [9]. Other methods include thallium stress testing and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, which may also be helpful in the diagnosis of CCS [9]. Triple-phase bone scan and single-photon emission computed tomography scans can be used to rule out other conditions in the differential diagnosis, such as medial tibial stress syndrome or stress fractures [11].

Treatment

Initial

Acute Compartment Syndrome

If the differential pressure is less than 30 mm Hg, treatment of ACS is surgical fasciotomy, which is described later [20]. In cases in which the differential pressure remains above 30 mm Hg, it has been shown to be safe to observe those patients with serial pressure measurements [21].

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

For CCS, the initial treatment consists of rest, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Counseling the patient to avoid running on hard surfaces, to use orthotics to control pronation, and to wear running shoes with the appropriate amount of cushion and a flared heel is important [7]. Surgery is usually reserved for symptoms persisting beyond 6 to 12 weeks, despite conservative therapy [13].

Rehabilitation

Acute Compartment Syndrome

The rehabilitation of ACS is limited to the postfasciotomy stage. Rehabilitation depends on the extent of the injury. Proper skin care for either the open area left to close by secondary intent or the skin grafts that have been applied is imperative. An ankle-foot orthotic to correct footdrop is often needed. Physical therapy is needed for gentle range of motion exercises to prevent contractures and should begin as soon after surgery as possible and as allowed by wound healing issues. Other measures include strengthening of muscles that may be only partially affected and gait training, possibly with an assistive device. There is no scientific literature to support any specific rehabilitation protocols, and so programs should be individualized on the basis of the particular patient’s needs. If the patient has deficits in activities of daily living, such as dressing or transfers, occupational therapy may be helpful in addressing these areas.

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

Controversy exists about the success of conservative treatment of CCS [7]. Current recommendations are based on the initial use of PRICE (protection, rest, ice, compression, and elevation), with progression to reestablishing range of motion and soft tissue mobility, incorporating stretching, nerve gliding techniques, strengthening exercises, and incorporating biomechanical analysis of the patient during sport-specific activity [28]. Evaluating and identifying the underlying cause, such as excessive pronation, is important in considering the rehabilitation course. Treatment of excessive pronation includes establishing normal muscle lengths throughout the kinetic chain, especially stretching the gastrocnemius and posterior tibialis, and strengthening the anterior tibialis [29]. Shoe orthoses to address excessive pronation may also be helpful. Training errors, such as rapid increases in intensity or duration, are addressed and corrected. In addition, soft tissue mobilization and manipulation techniques, including massage, myofascial stretching, and taping, may increase fascial compliance. This would address the proposed pathophysiologic process involving increased facial thickness, stiffness, and increased pressure [28].

If fasciotomy is done for CCS, postsurgical rehabilitation should follow. Weight bearing is permitted as tolerated, and gentle range of motion exercises are begun 1 to 2 days postoperatively. Strengthening and gradual return to activity begin at 1 to 2 weeks. Full return to activity such as running usually takes 8 to 12 weeks [30].

Procedures

Procedures are not typically done in compartment syndrome except as stated earlier to measure compartmental pressures as a diagnostic procedure.

Surgery

Acute Compartment Syndrome

Fasciotomy should be performed for ACS as soon as possible. Large longitudinal incisions are made in the affected compartment. These incisions are left open to be closed gradually, or split-thickness skin grafts are applied. Results of the surgery are variable and depend on the length of time of ischemia and other injuries involved [31]. Newer techniques allow fasciotomy to be performed with endoscopy and minimally invasive incisions [11,13]. Controversy exists as to whether all four compartments need to be released in cases of ACS. One study showed that release of only the anterior compartment had equivalent results to release of the anterior and lateral compartments [32]. If treatment is delayed for more than 12 hours, it is assumed that permanent damage has occurred to the muscles and nerves in the involved compartment. Late reconstruction procedures can be done, if necessary, to correct muscle contractures or to perform tendon transfers for footdrop [31].

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

Fasciotomy is also the mainstay for surgical treatment of CCS [7]. Different techniques for fasciotomy have been described. Most consist of making a small incision in the skin and then releasing the fascia as far proximally and distally as possible while avoiding nerves and vessels. Results of surgery are usually good, with average success rates of 80% to 90% as defined by a decrease in symptoms and a return to sports [30].

Potential Disease Complications

Acute Compartment Syndrome

In ACS, ischemia of less than 4 hours usually does not cause permanent damage. If ischemia lasts more than 12 hours, severe damage is expected. Ischemia of 4 to 12 hours can also cause significant damage, including muscle necrosis, muscle contractures, loss of nerve function, infection, gangrene, myoglobinuria, and renal failure. Amputation of the affected limb is sometimes necessary, and even death may occur from the systemic effects of necrosis or infection [1,3,7]. Recurrence has also been known to develop. Calcific myonecrosis can also be a late side effect [33].

Chronic Compartment Syndrome

If CCS is left untreated, it may become acute in presentation and result in irreversible sequelae [13].

Potential Treatment Complications

ACS fasciotomy has serious complications. Mortality rates are 11% to 15%, and serious morbidity is common, including amputation rates of 10% to 20% and diminished limb function in 27% [34].

CCS fasciotomy is a less extensive surgery on a healthier population. Complications are uncommon but can include bleeding, infection, deep venous thrombosis, wound infection, lymphocele, and nerve injury, particularly to the superficial peroneal nerve. Case series report a recurrence rate of 3% to 20%. The most common reasons for recurrence are excessive scar tissue formation, causing the compartment to become tight again, and inadequate fascial release. A case series exploring the outcome of repeated fasciotomy for recurrence of symptoms reported that 70% of patients had good or excellent outcomes [35].

One potential long-term complication of fasciotomy is an increased risk for development of chronic venous insufficiency caused by the loss of the calf musculovenous pump [36].