CHAPTER 65 Spinal Anesthesia

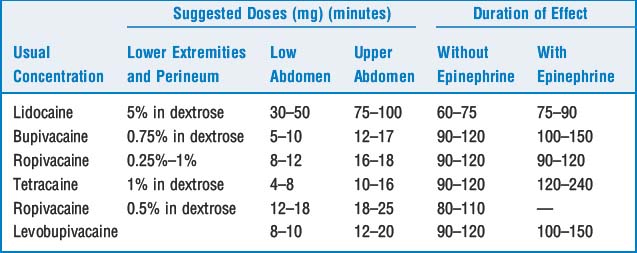

2 What are the usual doses of common local anesthetics used in spinal anesthesia and the duration of effect?

5 Describe the factors involved in distribution (and extent) of conduction blockade

Patient characteristics include height, position, intra-abdominal pressure, anatomic configuration of the spinal canal, and pregnancy. There is great interindividual variation in lumbosacral CSF volumes; magnetic resonance imaging has shown volumes ranging from 28 to 81 ml. Lumbar CSF volumes correlate well with the height and regression of the block. With the exception of an inverse relation with weight, no external physical measurement reliably estimates lumbar CSF volumes. CSF volumes are also reduced in pregnancy.

Patient characteristics include height, position, intra-abdominal pressure, anatomic configuration of the spinal canal, and pregnancy. There is great interindividual variation in lumbosacral CSF volumes; magnetic resonance imaging has shown volumes ranging from 28 to 81 ml. Lumbar CSF volumes correlate well with the height and regression of the block. With the exception of an inverse relation with weight, no external physical measurement reliably estimates lumbar CSF volumes. CSF volumes are also reduced in pregnancy. The total injected dose of local anesthetic is important, whereas the volume or concentration of injectant is unimportant.

The total injected dose of local anesthetic is important, whereas the volume or concentration of injectant is unimportant. The baricity of the local anesthetic solution is important. Baricity is defined by the ratio of the density of the local anesthetic solution to the density of CSF. A solution with a ratio >1 is hyperbaric and tends to sink with gravity within the CSF. An isobaric solution has a baricity of 1 and tends to remain in the immediate area of injection. A ratio <1 is a hypobaric solution, which rises in the CSF.

The baricity of the local anesthetic solution is important. Baricity is defined by the ratio of the density of the local anesthetic solution to the density of CSF. A solution with a ratio >1 is hyperbaric and tends to sink with gravity within the CSF. An isobaric solution has a baricity of 1 and tends to remain in the immediate area of injection. A ratio <1 is a hypobaric solution, which rises in the CSF.6 At what lumbar levels should a spinal anesthetic be administered? What structures are crossed when performing a spinal block?

8 What are the physiologic changes and risk factors found with subarachnoid block–associated hypotension?

10 Why are patients who have received spinal anesthetics especially sensitive to sedative medications? What is deafferentation?

12 If a patient has a cardiac arrest while having a subarachnoid block, how should resuscitative measures differ from standard advanced cardiac life support protocols?

17 Review the current recommendations for administering regional anesthesia to patients with altered coagulation caused by medications

Patients on thrombolytic/fibrinolytic therapy should not receive regional anesthesia except in the most extreme circumstances. Patients who have had regional anesthesia before such therapy has been instituted should receive serial neurologic checks.

Patients on thrombolytic/fibrinolytic therapy should not receive regional anesthesia except in the most extreme circumstances. Patients who have had regional anesthesia before such therapy has been instituted should receive serial neurologic checks. Oral anticoagulants should be stopped 4 to 5 days before the planned procedure, and prothrombin time/International Normalized Ratio normalized.

Oral anticoagulants should be stopped 4 to 5 days before the planned procedure, and prothrombin time/International Normalized Ratio normalized. Concurrent administration of medications that affect bleeding by different mechanisms (e.g., antiplatelet drugs, aspirin, heparin) complicates the decision to perform regional anesthesia; therefore decisions must be individualized. Patients taking only nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs can safely have either single-shot or catheter regional anesthetics.

Concurrent administration of medications that affect bleeding by different mechanisms (e.g., antiplatelet drugs, aspirin, heparin) complicates the decision to perform regional anesthesia; therefore decisions must be individualized. Patients taking only nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs can safely have either single-shot or catheter regional anesthetics.18 Should spinal (or epidural) anesthesia be performed when unfractionated heparin is administered?

If heparin is to be administered, coexisting thrombocytopenia, antiplatelet medications, oral anticoagulants, and other bleeding dyscrasias suggest that regional techniques should be avoided.

If heparin is to be administered, coexisting thrombocytopenia, antiplatelet medications, oral anticoagulants, and other bleeding dyscrasias suggest that regional techniques should be avoided. The subcutaneous administration of minidose unfractionated heparin is not contraindicated. but it is best to time performance of the block when the heparin effect is minimal. Similarly, a heparin dose should be held if it is scheduled soon after performance of the block.

The subcutaneous administration of minidose unfractionated heparin is not contraindicated. but it is best to time performance of the block when the heparin effect is minimal. Similarly, a heparin dose should be held if it is scheduled soon after performance of the block. In vascular patients who will receive large doses of heparin, avoid regional techniques if other coagulopathies are present, delay heparin administration for at least 1 hour after the procedure, and time removal of the catheter for when heparin effect has diminished (1 hour before subsequent doses or 2 to 4 hours after the last dose). There are no data to guide in decision making should a bloody tap occur.

In vascular patients who will receive large doses of heparin, avoid regional techniques if other coagulopathies are present, delay heparin administration for at least 1 hour after the procedure, and time removal of the catheter for when heparin effect has diminished (1 hour before subsequent doses or 2 to 4 hours after the last dose). There are no data to guide in decision making should a bloody tap occur.19 Should spinal (or epidural) anesthesia be performed when low-molecular-weight heparin is administered?

Patients who have received low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) should be believed to have altered coagulation, and a single-shot spinal injection is the safest procedure for these patients. As in the case with unfractionated heparin, other factors that increase the likelihood of bleeding will increase the risk of spinal hematoma when LMWH is administered.

Patients who have received low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) should be believed to have altered coagulation, and a single-shot spinal injection is the safest procedure for these patients. As in the case with unfractionated heparin, other factors that increase the likelihood of bleeding will increase the risk of spinal hematoma when LMWH is administered. Timing of the neuraxial procedure and dosing LMWH is extremely important, as is the dose of LMWH. Needle placement should occur at least 10 to 12 hours after an LMWH dose. Neuraxial procedures should be delayed for 24 hours when the patient is receiving larger LMWH doses: enoxaparin 1 mg/kg q12h, enoxaparin 1.5 mg/kg daily, dalteparin 120 units/kg q12h, dalteparin 200 units/kg daily, or tinzaparin 175 units/kg.

Timing of the neuraxial procedure and dosing LMWH is extremely important, as is the dose of LMWH. Needle placement should occur at least 10 to 12 hours after an LMWH dose. Neuraxial procedures should be delayed for 24 hours when the patient is receiving larger LMWH doses: enoxaparin 1 mg/kg q12h, enoxaparin 1.5 mg/kg daily, dalteparin 120 units/kg q12h, dalteparin 200 units/kg daily, or tinzaparin 175 units/kg. A bloody spinal tap should not cause cancellation of the surgery but should delay administration of LMWH by 24 hours.

A bloody spinal tap should not cause cancellation of the surgery but should delay administration of LMWH by 24 hours. If a patient is to have an epidural catheter for postoperative pain management and is also to receive LMWH after surgery, twice daily dosing has a greater risk of spinal hematoma formation than single daily dosing, and the benefits of an epidural catheter in a patient receiving twice-daily dosing should be weighed against the risks. Although some authorities are more aggressive, a safe practice is to delay the first dose for at least 24 hours after surgery, and a catheter should be removed a minimum of 10 to 12 hours after the last dose of LMWH.

If a patient is to have an epidural catheter for postoperative pain management and is also to receive LMWH after surgery, twice daily dosing has a greater risk of spinal hematoma formation than single daily dosing, and the benefits of an epidural catheter in a patient receiving twice-daily dosing should be weighed against the risks. Although some authorities are more aggressive, a safe practice is to delay the first dose for at least 24 hours after surgery, and a catheter should be removed a minimum of 10 to 12 hours after the last dose of LMWH.21 What is transient neurologic syndrome and its cause?

KEY POINTS: Spinal Anesthesia

22 Since lidocaine is associated with TNS, what would be an appropriate local anesthetic selection for an ambulatory procedure?

1. Caplan R.A., Ward R.J., Posner K., et al. Unexpected cardiac arrest during spinal anesthesia: a closed claims analysis of predisposing factors. Anesthesiology. 1988;68:5-11.

2. Zaric D., et al. Transient neurologic symptoms after spinal anesthesia with lidocaine versus other local anesthetics: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:1811-1816.

3. Hocking G., Wildsmilth J.A.W. Intrathecal drug spread. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:568-578.

4. Moen V., Dahlgren N., Irestedt L. Severe neurological complications after central neuraxial blockades in Sweden 1990–1999. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:950-959.