CHAPTER 63 Sedation and Anesthesia Outside the Operating Room

1 What procedures outside the operating room require sedation or general anesthesia?

Radiologic procedures, including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and interventional radiology; often a lack of patient cooperation necessitates the need for anesthesia assistance

Radiologic procedures, including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and interventional radiology; often a lack of patient cooperation necessitates the need for anesthesia assistance Cardiac catheterizations, insertion of implantable cardiac defibrillators, coronary arteriography, radiofrequency ablation, and cardioversions

Cardiac catheterizations, insertion of implantable cardiac defibrillators, coronary arteriography, radiofrequency ablation, and cardioversions Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy, liver biopsy, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy, liver biopsy, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography2 What equipment and standards are necessary for safely conducting an anesthetic outside the operating room?

If inhalation anesthetics are to be used, an anesthesia machine complete with scavenging capabilities

If inhalation anesthetics are to be used, an anesthesia machine complete with scavenging capabilities Standard anesthetic drugs, airway equipment, and monitoring necessary for the intended anesthetic and the subsequent transport

Standard anesthetic drugs, airway equipment, and monitoring necessary for the intended anesthetic and the subsequent transport An emergency cart with a defibrillator, emergency drugs, and other equipment adequate to provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation

An emergency cart with a defibrillator, emergency drugs, and other equipment adequate to provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation3 What monitoring is necessary for administration of any anesthetic, regardless of whether it is in the operating room or elsewhere?

Oxygenation: During all anesthetics a quantitative method of assessing oxygenation such as pulse oximetry shall be used. When using an anesthesia machine, an oxygen analyzer with a low oxygen concentration limit alarm shall be used.

Oxygenation: During all anesthetics a quantitative method of assessing oxygenation such as pulse oximetry shall be used. When using an anesthesia machine, an oxygen analyzer with a low oxygen concentration limit alarm shall be used. Ventilation: At the very least, all patients undergoing an anesthetic will be assessed for qualitative clinical signs of ventilation such as observed chest excursion, movement of the reservoir breathing bag, or auscultation of breath sounds. When an endotracheal tube or laryngeal mask airway is inserted, its correct positioning must be verified by identification of carbon dioxide in the expired gas, and carbon dioxide must be monitored with capnography or capnometry.

Ventilation: At the very least, all patients undergoing an anesthetic will be assessed for qualitative clinical signs of ventilation such as observed chest excursion, movement of the reservoir breathing bag, or auscultation of breath sounds. When an endotracheal tube or laryngeal mask airway is inserted, its correct positioning must be verified by identification of carbon dioxide in the expired gas, and carbon dioxide must be monitored with capnography or capnometry. Circulation: Every patient receiving anesthesia shall have an electrocardiogram (ECG) continuously displayed throughout the anesthetic and shall have blood pressure and heart rate evaluated at least every 5 minutes. In addition, every patient receiving general anesthesia will have circulatory function continually evaluated by one of the following methods: palpation of a pulse, auscultation of heart sounds, monitoring of a tracing of intra-arterial pressure, or pulse oximetry.

Circulation: Every patient receiving anesthesia shall have an electrocardiogram (ECG) continuously displayed throughout the anesthetic and shall have blood pressure and heart rate evaluated at least every 5 minutes. In addition, every patient receiving general anesthesia will have circulatory function continually evaluated by one of the following methods: palpation of a pulse, auscultation of heart sounds, monitoring of a tracing of intra-arterial pressure, or pulse oximetry.4 How might anesthesiologists be involved in establishing standards for sedation and analgesia conducted by nonanesthesiologists?

5 Explain conscious sedation and the continuum of depth of anesthesia

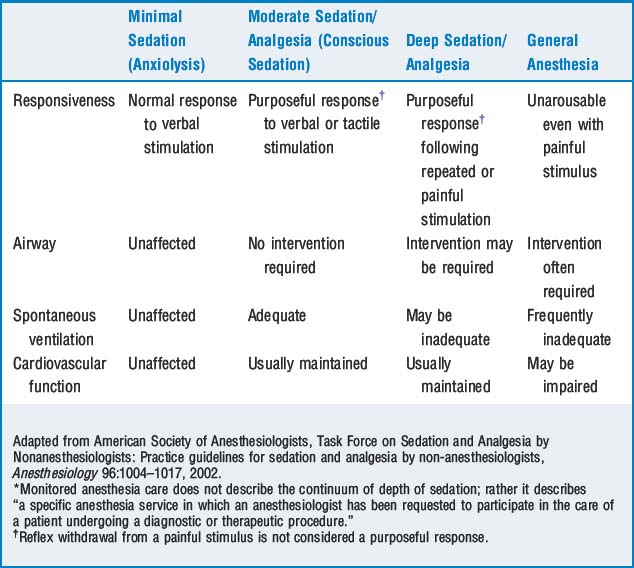

The ASA Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Nonanesthesiologists states that sedation and analgesia comprise a continuum of states ranging from minimal sedation to general anesthesia. Understanding the concept of the continuum of anesthesia is a critical first step for nonanesthesiologists to administer sedation and analgesia. The term conscious sedation, which is often used by nonanesthesiologists to refer to sedation administered in settings other than the operating room, is considered moderate sedation/analgesia and is defined in Table 63-1.

6 What are some of the requirements for the administration of moderate sedation by nonanesthesiologists?

A presedation or preanesthesia assessment must be performed for each patient before beginning sedation or anesthesia.

A presedation or preanesthesia assessment must be performed for each patient before beginning sedation or anesthesia. Before undergoing anesthesia or sedation, each patient must be provided preprocedural treatment, services, and education according to his or her plan of care.

Before undergoing anesthesia or sedation, each patient must be provided preprocedural treatment, services, and education according to his or her plan of care. Before administering sedating medications, a licensed independent practitioner must plan, or must concur with the plan, for sedation or anesthesia.

Before administering sedating medications, a licensed independent practitioner must plan, or must concur with the plan, for sedation or anesthesia. A sufficient number of qualified staff must be on hand to evaluate the patient, provide sedation/anesthesia, help with the procedure, and monitor and recover the patient.

A sufficient number of qualified staff must be on hand to evaluate the patient, provide sedation/anesthesia, help with the procedure, and monitor and recover the patient. Individuals administering sedation or anesthesia must be qualified and have credentials to manage and rescue patients at whatever level is achieved, either intentionally or unintentionally. Thus a practitioner administering deep sedation/analgesia to a patient must be prepared for the patient to slip into general anesthesia, during which time the patient may require intubation, positive-pressure ventilation, and cardiovascular stabilization.

Individuals administering sedation or anesthesia must be qualified and have credentials to manage and rescue patients at whatever level is achieved, either intentionally or unintentionally. Thus a practitioner administering deep sedation/analgesia to a patient must be prepared for the patient to slip into general anesthesia, during which time the patient may require intubation, positive-pressure ventilation, and cardiovascular stabilization.12 What are some of the more common manifestations of the reactions to soluble contrast media?

| Mild | Moderate | Life-Threatening |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea | Vomiting | Glottic edema/bronchospasm |

| Headache | Rigors | Pulmonary edema |

| Perception of warmth | Feeling faint | Life-threatening arrhythmias |

| Mild urticaria |

13 How is radiation exposure measured?

The roentgen equivalent in humans (rem) is a measure of equivalent dose and relates the absorbed radiation dose in human tissue to the effective biologic damage of the radiation. Equivalent doses are often expressed in terms of thousandths of a rem, or mrem. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that the general adult public limit their annual radiation dose to 5000 mrem/year. The equivalent doses from various sources are listed in Table 63-3.

TABLE 63-3 Equivalent Radiation Doses for Medical Procedures

| Medical Procedures | Equivalent Doses |

|---|---|

| Chest x-ray | 8 mrem |

| Extremities x-ray | 1 mrem |

| Dental x-ray | 10 mrem |

| Cervical spine x-ray | 22 mrem |

| Pelvis x-ray | 44 mrem |

| Upper gastrointestinal series | 245 mrem |

| Lower gastrointestinal series | 405 mrem |

| Computed tomography (whole body) | 1100 mrem |

| Background Sources of Radiation | |

| Coast-to-coast airplane roundtrip | 5 mrem |

| Average U.S. cosmic radiation | 27 mrem/year |

| Average U.S. terrestrial radiation | 28 mrem/year |

| Average dose to U.S. public from all sources | 360 mrem/year |

| Recommended Radiation Exposure Limits | |

| Occupational dose limit | 5000 mrem/year |

| Occupational exposure limit for minors | 500 mrem/year |

| Occupational exposure limits for pregnant females | 500 mrem/gestation |

mrem, Roentgen equivalent in humans (in thousandths).

14 How can anesthesiologists protect themselves from radiation exposure?

Maximize the distance to the source: Newton’s inverse square law, which applies to any point source that spreads its influence in all directions (such as light, sound, gravitational field) tells us that the intensity of the radiation at a given radius is the source strength divided by the sphere area. Or, put more plainly, the intensity (I) of radiation is inversely related to the square of distance (d) from the source:

Maximize the distance to the source: Newton’s inverse square law, which applies to any point source that spreads its influence in all directions (such as light, sound, gravitational field) tells us that the intensity of the radiation at a given radius is the source strength divided by the sphere area. Or, put more plainly, the intensity (I) of radiation is inversely related to the square of distance (d) from the source:

Minimize the time of exposure: Most medical occupational radiation exposure comes from x-rays scattered by both the patient and surrounding equipment. Obviously this scatter occurs only when the machine is on. A person’s radiation exposure is directly proportional to the length of exposure; thus every reasonable effort to limit the time of exposure is beneficial.

Minimize the time of exposure: Most medical occupational radiation exposure comes from x-rays scattered by both the patient and surrounding equipment. Obviously this scatter occurs only when the machine is on. A person’s radiation exposure is directly proportional to the length of exposure; thus every reasonable effort to limit the time of exposure is beneficial. Use shields: Most aprons contain the equivalent of 0.25 to 0.5 mm of lead, which is effective at blocking most scattered radiation in medical settings. Uncovered areas such as the lens of the eye still run the risk of radiation exposure. Other shields such as concrete walls and portable barriers should be used whenever possible. Lead aprons should be x-rayed periodically to determine if they are still effective barriers because they are known to deteriorate with lime particularly if mishandled.

Use shields: Most aprons contain the equivalent of 0.25 to 0.5 mm of lead, which is effective at blocking most scattered radiation in medical settings. Uncovered areas such as the lens of the eye still run the risk of radiation exposure. Other shields such as concrete walls and portable barriers should be used whenever possible. Lead aprons should be x-rayed periodically to determine if they are still effective barriers because they are known to deteriorate with lime particularly if mishandled.15 Define the unique problems associated with providing an anesthetic in the magnetic resonance imaging suite

16 What modifications in the anesthesia machine, ventilator, and monitoring equipment must be made to provide an anesthetic in the magnetic resonance imaging suite?

KEY POINTS: Anesthesia Outside the Operating Room

1. American Society of Anesthesiologists: Guidelines for nonoperating room anesthetizing locations (last amended on October 15). Park Ridge, Ill.

2. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Nonanesthesiologists: practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004-1017.

3. Carollo D.S., Nossaman B.D., Ramadhyani U. Dexmedetomidine: a review of clinical applications. Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2008;21:457-461.

4. Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals: The Official Handbook, effective January 2009, Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, pp PC 17–18, RC 5–7, RI 5

5. Kotob F., Twersky R.S. Anesthesia outside the operating room: general overview and monitoring standards. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2003;41:1-15.

6. MacKenzie R.A., Southom P., Stensrud P.E. Anesthesia at remote locations. In: Miller R.D., editor. Anesthesia. ed 5. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:2241-2269.