CHAPTER 62

Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome

Michael Fredericson, MD; Cindy Lin, MD; Kelvin Chew, MBBCh, MSpMed

Definition

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS) is a common cause of lateral extra-articular hip pain. GTPS is clinically characterized by peritrochanteric pain and focal tenderness [1]. GTPS describes a continuum of disorders with causes ranging from gluteus medius and minimus tears, tendinitis, or tendinopathy to trochanteric bursitis and external coxa saltans [2]. Previously, it was thought that excessive gluteal tendon friction at the greater trochanter attachment led to subgluteus maximus bursal inflammation; hence, it was called greater trochanteric bursitis [3]. However, histopathologic and imaging studies have not identified bursal inflammation as a consistent finding, thus leading to the current clinical description of this entity as GTPS [2].

The peak incidence of GTPS is between the fourth and sixth decades of life. It occurs four times more frequently in women than in men, which may be due to gender differences in pelvic and lower limb biomechanics [4,5]. It affects up to 10% of the general population and has been reported in up to 20% of patients with low back pain [5,6]. GTPS can result from direct macrotrauma after contusions from falls or contact sports [7]. However, it is more often due to cumulative microtrauma and abnormal loading forces on the gluteus medius and minimus tendons inserting on the greater trochanter. It has been suggested that gluteal tendon degeneration and tears at the greater trochanter attachment may induce secondary reactive inflammation in the bursae [4]. Contributing factors include hip or knee osteoarthritis, lumbar spine degenerative disorders, obesity, true or functional leg length discrepancies, gait abnormalities, and iliotibial band tightness [5,6,8]. GTPS can also occur after hip surgery, such as femoral osteotomy [9], hip joint replacement, or arthroscopic surgery, and from postoperative hip abductor weakness. Less common causes to consider in the differential diagnosis include infection and inflammatory arthritis if there are systemic symptoms and signs, lateral hip swelling, redness, or heat [10–12].

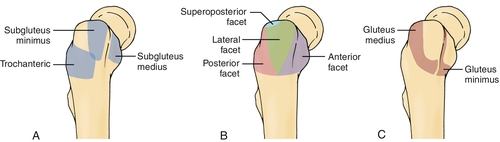

The greater trochanter of the femur is the insertion site of the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis, and obturator internus muscles, and it is also the origin of the vastus lateralis muscle [13]. Three main bursae surround the greater trochanter, including the subgluteal maximus, medius, and minimus bursae [14]. The subgluteus maximus bursa is the largest bursa and lies lateral to the greater trochanter beneath the gluteus maximus and iliotibial tract. The subgluteus medius bursa lies deep beneath the gluteus medius tendon and posterosuperior to the lateral facet of the greater trochanter. The subgluteus minimus bursa lies beneath the gluteus minimus tendon at the anterosuperior edge of the greater trochanter. The subgluteus maximus bursa is most often involved in cases of trochanteric bursitis [3].

Symptoms

The main clinical symptom is lateral hip pain at the greater trochanteric region. The pain can radiate down the lateral aspect of the thigh as a pseudoradiculopathy that does not extend past the knee. Symptoms are exacerbated by hip movements, in particular external rotation and abduction. Pain may also be provoked by standing, walking, stair climbing, crossing the legs, running, or running on banked surfaces. Recent changes in physical activity or sports training programs may precede symptoms. Sleep may be affected with pain aggravated by lying in the lateral decubitus position directly on the affected side or from lying with the affected side up and in passive hip adduction.

Physical Examination

In GTPS, localized tenderness is found on direct palpation of the greater trochanter. Lateral hip pain may be reproduced on examination with resisted hip abduction with the patient in a side-lying position. Pain can also be elicited with active hip internal or external rotation at 45 degrees of hip flexion [15].

Evaluation for gait, hip, or spine disorders and leg length discrepancy is important as abnormal motion and joint loading in one region of the kinetic chain can contribute to the development of GTPS. The Trendelenburg sign can be seen in GTPS as a result of weakness or inhibition of the hip abductor muscles [16]. The gluteus medius and minimus play an important role in hip abduction and pelvic stabilization during gait. In GTPS, with weight bearing on the affected limb during single-leg stance, the hip abductors are unable to stabilize the pelvis, resulting in contralateral pelvic drop [17]. Activity-related pain, particularly in the anterior groin, or restricted hip range of motion may indicate intra-articular hip disease, such as osteoarthritis, femoroacetabular impingement, or labral disorders that warrant further investigation. Lumbosacral radiculitis or radiculopathy should be ruled out with detailed history and neurologic examination; the neurologic examination findings should be normal in GTPS.

Functional Limitations

GTPS can limit activity and mobility and cause further weakness of the lateral hip rotator muscles and deconditioning. This can have an impact on basic activities of daily life, including walking, running, and stair climbing. Pain may also interrupt sleep.

Diagnostic Studies

Laboratory studies, although seldom required, should be performed if an infectious or rheumatologic process is suspected. The diagnosis of GTPS can usually be made by history and physical examination. Imaging studies are used mainly to exclude other underlying causes of lateral hip pain or when symptoms do not respond to conservative treatments.

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in cases in which there is clinical concern for other causes of lateral hip pain. Magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasonography can be used to detect tendinopathy, muscle tears, cortical irregularity, bursal fluid or thickening, or muscle atrophy [18,19]. The identification of bursal fluid on magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound examination is thought to be a secondary manifestation of local disease rather than the primary process in most cases of GTPS [18].

Ultrasound examination can be helpful in visualizing the muscle insertions on the facets of the greater trochanter to localize the pathologic process. The insertion for the gluteus minimus tendon is the anterior facet; for the gluteus medius tendon, the lateral and superolateral facets; and for the subgluteal maximus and trochanteric bursa, the posterior facet (Fig. 62.1) [20]. A “bald” facet, with absence of the tendinous insertion, suggests a complete tear. Anechoic defects within the tendon suggest partial tears. Gluteal tendinosis on ultrasound examination is identified by tendon thickening, heterogeneous signal, and decreased echogenicity [18].

Hip plain films may demonstrate calcifications in the region of the bursa or in the gluteal tendon insertions related to calcific tendinosis [2,18].

Treatment

Initial

Initial treatment is to provide acute pain relief through icing, analgesic pain medications, and sports and activity modification, such as avoidance of stair climbing and other exacerbating activities. Direct pressure on the painful lateral hip should be avoided; as such, recommendations on sleep positioning can be given. Gentle stretching of the iliotibial band, tensor fascia lata, and gluteal muscles is encouraged with avoidance of end-range hip motion in the acute phase.

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy entails a combination of strengthening, stretching, and correction of identifiable underlying spine or hip disorders that precipitated GTPS. Strengthening should focus on the core and hip abductors, extensors, and external rotators with progression to eccentric loading of the gluteal muscles in cases of tendinopathy. Myofascial soft tissue release, stretching, or therapeutic ultrasound may be helpful for the tensor fascia lata–iliotibial band complex.

Focal ice massage may be useful at the outset of the injury. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy can be beneficial for pain relief during the subacute to chronic phases [21]. Addressing gait abnormalities through orthotics or assistive devices, such as walkers or canes, should also be considered. Weight loss is advised in obesity.

Procedures

For cases unresponsive to noninvasive treatments, corticosteroid injections combined with local anesthetic can be used. Whereas some studies have found corticosteroid injections to be effective in the short term in improving pain and activity, other studies report incomplete long-term relief and symptom recurrence [21–24]. The injection technique involves the patient’s lying in the lateral decubitus position with the affected side up and the knees flexed comfortably. The point of maximal tenderness over the greater trochanter is identified and marked. Under sterile conditions, a syringe with a 25-gauge needle, containing triamcinolone (40 mg) with 1% lidocaine (3 to 4 mL), is advanced until contact is made with the greater trochanter bone; the needle is then withdrawn 3 or 4 mm. Once negative aspiration has verified that the needle is not intravascular, the solution is introduced after a lack of resistance is detected. Patients are reevaluated within a month after injection to assess therapeutic response.

Ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance may be used to enhance precise injection placement. However, fluoroscopically guided trochanteric injections have not been found to be superior to blind injections in terms of patient outcomes and are associated with increased cost [24]. Caution must be exercised with repeated injection because it may be associated with muscle and tendon weakening or rupture [25].

Surgery

In refractory cases and if significant functional limitations are present, surgery can be considered. Depending on the underlying pathologic process, this may involve arthroscopic bursectomy [26], iliotibial band release or lengthening, or open or endoscopic gluteal tendon repair [20,27,28].

Potential Disease Complications

GTPS should be a self-limited condition. If symptoms persist, consider other underlying causes. If the underlying predisposing factors are not appropriately addressed, the syndrome may progress to chronic pain, which can lead to muscle deconditioning, hip abductor muscle weakness, functional decline, and increased risk of falls in elderly or frail patients.

Potential Treatment Complications

Complications from anti-inflammatory medications include drug hypersensitivity, gastric ulceration, and renal toxicity. Complications from corticosteroid injections include bleeding, bruising, infection, drug hypersensitivity reactions, tendon ruptures, nerve injury, fat atrophy, and skin hypopigmentation [23,25].