CHAPTER 61

Total Hip Replacement

Juan A. Cabrera, MD; Alison L. Cabrera, MD

Definition

Total hip arthroplasty (THA), commonly called hip replacement surgery, involves the reconstruction of a diseased, damaged, or ankylosed hip joint. The most common causes of adult hip disease are osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritides, avascular necrosis, post-traumatic degenerative joint disease, congenital hip disease, oncologic bone disease, and infection involving the hip joint. The surgical treatment of hip arthritides has evolved from the first excisional arthroplasty by Anthony White in 1821 into the modern THA [1]. The modern era of hip joint replacement began in the late 1960s when Sir John Charnley combined a stainless steel femoral component with a polyethylene socket fixed to the adjacent acetabulum with polymethyl methacrylate (cement). Since that time, arthroplasty of the hip joint has become an accepted and standard treatment of common adult hip joint disease. Modern hip arthroplasty surgery has resulted in the restoration of pain-free motion and improved quality of life for millions [2]. Total joint arthroplasty, including hip and knee, has become the most common elective surgical procedure performed in the United States, with more than one million performed in 2009 [3]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 327,000 total hip replacements were performed in the United States in 2009 [3].

Hip joint arthroplasty can be divided into either THA, which provides a prosthetic replacement of the proximal femur and acetabulum, or hemiarthroplasty, which replaces the proximal femur while leaving the native acetabulum intact. Hip hemiarthroplasty is reserved for patients with a healthy articular surface in the acetabulum and is most commonly seen after proximal femur fractures. The focus of this chapter is on THA, which is the preferred surgical option for patients with degenerative changes affecting both the femur and acetabulum. Further categorization for hip arthroplasty can be made by prosthetic hardware components, surgical approach, or fixation method of the prosthesis (cement versus biologic or “press-fit” integration). Surgical decision-making for hardware type, approach, and prosthetic fixation is beyond the scope of this chapter, but it is important to note that there are no published consensus guidelines on best prostheses, approach, or fixation method among surgeons performing total hip arthroplasties.

Symptoms

The primary symptom of hip disease is groin pain, but patients may also have associated back and knee pain. Patients may describe a decline in mobility, self-care, and activities of daily living. They may present with an abnormal gait or may describe difficulty in walking long distances and need for an assistive device. Donning their shoes or socks and taking them off and getting in and out of the seated position may be difficult daily activities. Inability to participate in recreational activities or light sports may be a presenting complaint.

Physical Examination

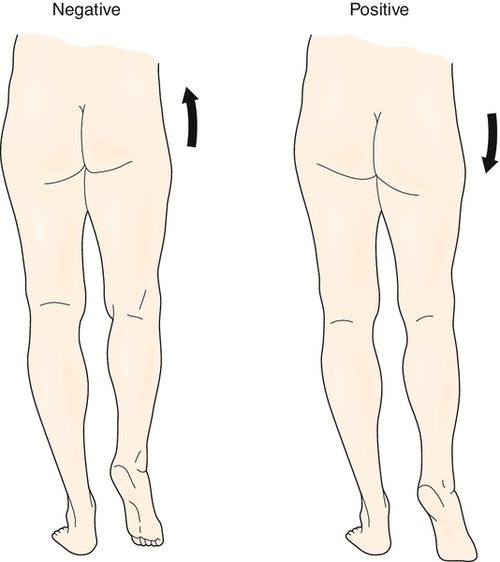

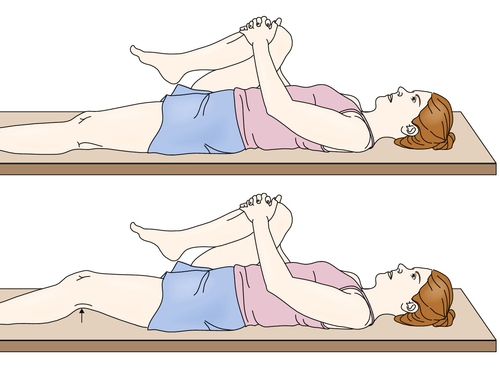

Patients with hip disease are likely to have physical examination findings that will require continued attention postoperatively (Table 61.1). The examiner should examine both hips, knees, and back for range of motion. Decreased range of motion of the affected hip will be found and may be the first physical examination finding in cases of mild disease. Also, a thorough neurovascular examination of all extremities should be performed. One of the most commonly observed examination findings is an antalgic (painful) gait pattern representing a combination of pain that inhibits motion, structural loss of joint motion, avoidance behavior, and weakness. Hip pain or weakness of the hip abductors can result in contralateral pelvic tilt or drop (Trendelenburg sign) with ipsilateral weight bearing (Fig. 61.1). Muscle weakness is typically not true neurologic weakness but rather represents a disuse weakness associated with pain and avoidance. A hip flexion contracture may be observed with the Thomas test (Fig. 61.2), and accentuated lumbar lordosis may be seen in those with a hip flexion contracture, which may result in secondary mechanical low back pain due to alteration of normal spine mechanics. A limb length discrepancy may be observed, with the affected hip being the shorter limb.

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations from severe hip disease include difficulty in walking and with all mobility, even rising from a seated position, because of pain and weakness. This may affect a patient’s ability to dress, to bathe, to perform household chores, to participate in recreational activities, and to work outside the home. The goal of THA is to improve pain and consequently to improve function with activities of daily living.

Diagnostic Studies

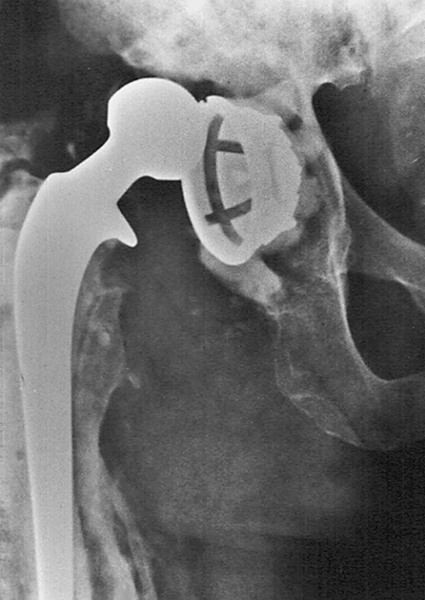

Plain radiography remains the primary imaging tool for evaluation of hip disease and for postoperative assessment of THA. On radiographic examination, significant loss of joint cartilage as demonstrated by joint space narrowing, joint incongruity, osteophyte formation, subchondral cysts, and sclerosis are seen in individuals being considered for THA (Fig. 61.3). Many postoperative complications after THA can be evaluated by plain radiography. In patients thought to have a dislocation after THA, radiographs should be obtained urgently because a true dislocation must be relocated expediently (Fig. 61.4). Plain radiographs are also obtained in patients thought to have prosthetic loosening or periprosthetic fracture (Fig. 61.5). If plain radiographs do not show pathologic changes in a patient with enigmatic hip pain after THA, magnetic resonance imaging can be done with minimal artifact and can demonstrate disease in the periprosthetic soft tissues, including synovitis, periprosthetic inflammation, osteolysis, and iliopsoas tendinitis [4]. A computed tomography scan or bone scan may be part of the evaluation for osteolysis or loosening and infection.

Treatment

Treatment protocols after THA can be broadly divided into an initial (acute postoperative) phase and a rehabilitation phase. All patients will have weight-bearing and activity restrictions for approximately 6 weeks postoperatively. These restrictions are not universally accepted, are influenced by surgical technique (cemented versus uncemented fixation of the prosthesis), and can vary by surgeon preference. Ultimately, postoperative restrictions should be clarified by communication with the surgeon.

Initial

The initial phase (acute postoperative) usually includes up to 4 days after surgery and is performed on an inpatient basis. Therapy typically begins on postoperative day 1 and focuses on getting the patient out of bed; education is provided on safe transfers, and static exercises are performed for gluteal muscles, quadriceps, and ankle pumps. Pain control strategies frequently begin with intravenous narcotics (patient-controlled analgesic pumps), cryotherapy, and appropriate education to reduce anxiety. Rehabilitation strategies on postoperative day 2 through the day of discharge should stress education on hip precautions, compliance with weight-bearing restrictions, early mobilization with use of an assistive device, instruction on the use of adaptive equipment for functional independence (bathing, grooming), and continued pain control [5]. Pain control should be transitioned to oral medications and may require any combination of non-narcotic analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, long-acting narcotics, or short-acting narcotics. Recently, intravenous acetaminophen has been shown to be a safe and effective pain medication in patients after joint replacement, which is of paramount importance considering the many side effects of narcotics in the elderly population [6]. Other interventions during the initial phase after THA include administration of perioperative prophylactic antibiotics, autologous blood transfusions for blood loss–induced anemia, and initiation of deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis. The patient may be receiving pharmacologic or mechanical deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis based on current clinical practice guidelines and individual patient factors [7]. By the third postoperative day, the patient should be able to tolerate 2 to 3 hours of therapy a day unless severe anemia or other medical problems result in further functional limitations. If the patient’s condition is stable, the patient is ready for discharge from the acute care hospital by the third or fourth postoperative day.

Rehabilitation

Once the initial (acute postoperative) phase is complete, a decision needs to be made for the most appropriate environment for the rehabilitation phase. This decision is based on physical and social factors and should be made with the patient, the patient’s primary caregiver, surgeon, physiatrist, therapists, nursing staff, and social worker. Goals for rehabilitation after THA should be to restore maximal range of motion, to minimize pain, to improve muscle strength, to promote ambulation, and to facilitate functional independence (Table 61.1).

Hip precautions should be followed and are taught to patients to minimize the possibility of hip dislocation. Patients with weak periarticular tissues, revision surgeries, or previous dislocations are at the highest risk for a dislocation, which is greatest during the first postoperative week. Most surgeons use a posterolateral approach to the hip joint and dislocate the joint by hyperflexion (greater than 90 degrees), adduction, and internal rotation. After hip replacement, that combination of movements increases the risk of dislocation. Therefore, an abduction pillow or wedge can be placed between the legs to maintain a safe position. Patients are taught not to use low chairs or to reach forward by flexing at the hip. Many surgeons who perform THA by anterior and anterolateral approaches are advocates for these approaches because of a lessened risk of dislocation. There is level II evidence suggesting that the risk of hip dislocation is reduced with a direct anterior or anterolateral approach, and strict hip precautions are not necessary [8]. There is little information in the literature to guide the duration of hip precautions. Most surgeons encourage strict precautions for at least 6 weeks and some encourage these precautions indefinitely. The performing surgeon should clarify the prescription of hip precautions, including restricted movements and duration of precautions, before initiating any rehabilitation protocol.

Active-assisted range of motion and strengthening exercises are progressed as tolerated. Resisted hip exercises should be avoided in the first 4 to 6 weeks to prevent excessive torsional forces on the implant [5]. Strengthening exercises for knee extension are encouraged. Quadriceps weakness can persist for up to 1 year after THA if it is not addressed during rehabilitation [5]. Electrical stimulation can be used for patients with atrophy of the quadriceps. Range of motion including stretching exercises for the hip flexor and adductor muscles should be included to prevent gait abnormalities. Subjective leg length discrepancy (typically longer on the side of THA) is commonly corrected with improved posture and stretching of hip abductor muscles [5].

Early protected ambulation progresses toward independent mobility as tolerated on the basis of the individual’s response and weight-bearing restrictions. Ambulation training after THA begins with appropriate assistive devices, such as a rolling walker. Weight-bearing restrictions in the postoperative phase are used to prevent “out of plane” or torsional forces on the implant. Patients should be taught to ascend stairs one step at a time and should lead with the contralateral limb to avoid torsional forces on the implant [5]. Determination of weight-bearing restrictions is made by surgeon preference and surgical technique; little literature exists to support consensus guidelines for weight-bearing restrictions after THA. However, there is some evidence to support early rehabilitation with unrestricted weight bearing after uncemented THA with a reciprocating gait pattern [9]. These patients should use protected weight bearing with stair climbing during the first weeks after surgery because of excessive forces through the hip [9]. Most patients should be able to ambulate community distances, initially with a walker or a cane, and then advance to ambulation without an assistive device or return to their presurgical baseline within 4 to 12 weeks after hip arthroplasty. The rate of advancement in gait training is usually limited by the weight-bearing status established at the time of surgery.

Postoperative gait changes include decreased velocity, decreased stride length, decreased sagittal hip range of motion, reduced peak hip abduction, and increased peak hip flexion and extension moments [10]. Gait symmetry and velocity at 1 year after THA were most improved with supervised rehabilitation focusing on muscle strengthening and motor relearning [11].

The existing literature does not allow us to draw definitive conclusions on sports in general or high-risk activity after THA [12]. Most surgeons agree that patients should avoid contact or high-impact athletic activity after THA. Some patients can return to noncontact, low-impact athletic activity between 3 and 6 months after surgery; however, the true relationship between athletic activity and rate of revision surgery remains unclear [12]. Patients should be counseled of the details of possible complications, prosthesis failure, and revision surgery before resuming athletic activity [12].

Activities of daily living are assessed, and each individual’s unique needs and goals drive the specific, individualized plan of care and treatments given. Upper and lower body bathing and dressing within hip and weight-bearing precautions are essential components of the rehabilitation program. Appropriate adaptive equipment including sock aids, reachers, and dressing sticks to perform lower body self-care should be provided. Bathroom transfers and kitchen activities are also incorporated into the rehabilitation program. Often, raised toilet seats or commodes and tub transfer benches are helpful and necessary to prevent excessive hip flexion and dislocation in the sitting position.

Discharge planning to the next level of care, including durable medical equipment, medical follow-up, and follow-up rehabilitation services (either in the home or in the community), must be communicated to the patient and family. Discharge to an inpatient rehabilitation facility has been influenced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which has determined that hospitals are eligible for payment of rehabilitation after total joint arthroplasty if (1) it is a bilateral procedure, (2) age is older than 85 years, or (3) body mass index is above 50. A typical total hip replacement clinical pathway or protocol for inpatient rehabilitation is now a 7- to 10-day program [13]. Many published sources outline the benefits as well as the elements of the total hip replacement clinical pathway; however, there is a need to update the literature, given the changes in surgical technique [14–16]. There is also a shift toward rapid discharge to home from acute care with an outpatient rehabilitation program, especially in the era of minimally invasive surgery [17]. A Cochrane review with silver level of evidence showed that early multidisciplinary rehabilitation can improve outcomes with regard to activity levels and postoperative participation [18]. There is a paucity of literature discussing the optimal intensity, frequency, cost-effectiveness, and long-term effects of early multidisciplinary rehabilitation.

Individuals who undergo THA revision surgery have a more difficult postoperative rehabilitation experience; they often show less progress in functional independence measures, longer rehabilitation length of stay, and greater hospital charges compared with patients undergoing primary hip replacement surgery. These differences in outcomes are even more pronounced if an infected prosthesis is the cause of the revision arthroplasty [19].

Procedures

Wound care, staple or suture removal, and Steri-Strip application are typically performed after THA.

Surgery

Most surgeons will consider THA if a patient is having severe pain that is affecting the patient’s quality of life, there are signs of degenerative joint disease on radiographs, and the patient has maximized conservative treatment options. However, there are no minimum standards or universally accepted criteria for patient selection. Patient selection may also be influenced by the patient’s ability to cooperate with the rehabilitation program after surgery, serious comorbid medical conditions, morbid obesity, high levels of activity, high fall risk, or younger age [20]. These factors can contribute to early failure and complications. Contraindications include local or systemic infection, neuromuscular compromise, dementia, poor bone quality, and poor vascular supply.

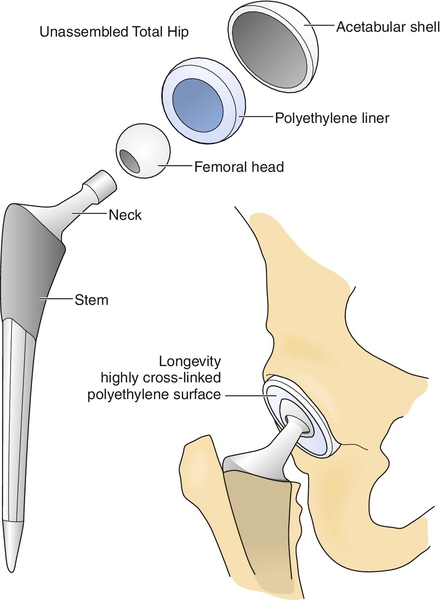

The THA components include a femoral stem, a femoral neck, a femoral head, and an acetabular shell or cup with a polyethylene liner (Fig. 61.6). This allows resurfacing of both sides of the hip joint and permits the highest degree of “customization” for each individual. Surgical technique and decision-making are beyond the scope of this text; however, there are some considerations that will have implications for rehabilitation.

Rehabilitation of THA will be affected by fixation techniques: cemented versus uncemented. The cemented technique is used only on the femoral component. After a cement restrictor plug is placed in the distal femoral canal, polymethyl methacrylate cement is freshly made and inserted into the femoral canal by pressurized cementing technique. Insertion of the femoral stem creates an intimate fit of the prosthesis to the intramedullary canal with a small circumferential cement mantle. Cement polymerization rigidly fixates the femoral component. Frequently, the patient with a cemented prosthesis is allowed to bear weight as tolerated immediately, whereas the individual with a noncemented press-fit prosthesis often must wait for 6 to 8 weeks before fully bearing weight to allow stability by bone ingrowth. Rehabilitation will also be affected if surgical technique includes trochanteric osteotomy. If a trochanteric osteotomy is performed during the surgery, hip abduction resistance exercises are usually restricted.

The changing population of patients undergoing THA is driving the current trends in THA. The high-demand, younger patient population with hip disease has led to the use of alternative bearing surfaces (ceramic-ceramic articulations, metal-on-metal articulations, and improved polyethylene surfaces). These alternative bearing surfaces are intended to improve durability and wear for highly active patients. There is growing interest in the orthopedic literature on the safety and outcomes of these alternative surfaces; however, there is no superior articulation at this time. Less invasive and minimally invasive approaches have been developed to facilitate rehabilitation and to decrease rehabilitation time. Navigation technology has been used in total knee arthroplasty but is now being considered to assist with implant positioning in hip replacement (particularly with the use of minimally invasive approaches). Bone-preserving techniques, including resurfacing techniques and short-stemmed femoral implants, have also been considered for the younger and more active patients undergoing THA. The long-term effects and outcomes of these trends have yet to be determined in the literature but are currently being studied.

Whereas all patient subgroups have demonstrated functional improvements from joint arthroplasty, younger age and male sex are associated with the increased risk of revision surgery. In one systematic review, older age and male sex are associated with increased mortality, and older age (particularly in women) is related to worse function after arthroplasty [21].

Potential Disease Complications

Common physical impairments of hip disease after THA include decreased muscle strength, limited hip range of motion, limited flexibility, and abnormalities of gait. Hip joint weakness has been shown to persist at 2 years after surgery, indicating a need for prolonged exercise. Current data suggest that THA patients continue to experience physical and functional limitations lasting at least 1 year postoperatively. Persistent groin pain after an otherwise successful surgery has been documented in as high as 18% of total hip arthroplasties [22]. Therefore it is reasonable to have patients continue with therapeutic exercises to address these limitations well beyond the early recovery period (first 12 weeks) [23,24].

Potential Treatment Complications

Perioperative and postoperative complications after THA include infection, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, dislocation, periprosthetic fracture, nerve injury, iliopsoas impingement, limb length inequality, anemia, bleeding, myocardial infarction, and death.

The incidence of deep venous thrombosis after total hip implantation without prophylactic anticoagulation is 45% to 57%; the incidence of proximal clot (defined as any thrombosis in the popliteal vein or more proximal) is between 23% and 36%; and the incidence of fatal pulmonary embolism is between 0.7% and 30% [25]. Clinical practice guidelines encourage surgeons to assess the thrombosis and bleeding risk for each individual patient and help guide which prophylactic treatment is indicated [6]. Postoperative limb swelling should trigger deep venous thrombosis surveillance screening with venous ultrasonography and Doppler wave signal analysis (commonly referred to as duplex scanning). If pulmonary embolism is suspected in a patient with hypoxia or shortness of breath, chest radiography, electrocardiography, and ventilation/perfusion scanning or computed tomographic pulmonary angiography are included as part of the evaluation.

Careful attention is given to treatment of anemia because patients with adequate hemoglobin levels generally tolerate activity well and progress in rehabilitation more readily than do those with low hemoglobin levels. Adequate nutrition, iron supplements, vitamins, and, if needed, erythropoietin can be used. Blood transfusions may be necessary if the hemoglobin level continues to drift downward and there is concern of hemodynamic instability or if the patient has symptoms or physical examination findings indicative of low perfusion status.

A hip dislocation is not subtle and should be suspected if the patient cannot endure weight bearing, the limb is acutely shortened and internally rotated, or the patient is intolerant of gentle hip motion because of excessive pain. A patient can usually give an exact moment or event that led to the dislocation. A dislocation often results in a significant functional setback as the patient is often more cautious and fearful of performing activities of daily living and mobility training. Reduction typically requires sedation and muscle relaxation and may require a return trip to the operating room.

Wound care of the incision line is accomplished with dry sterile dressing changes once or twice a day. Once wound drainage ceases, a dressing is no longer essential. Tape burns around the surgical incision are a common problem and can be treated with a hydrogel pad such as DuoDerm for approximately 1 week. Serous drainage without signs of erythema or induration is commonplace for 3 or 4 days postoperatively, but persistent drainage beyond 7 days should trigger clinical suspicion for wound infection. Wound problems should be communicated to the operative surgeon for collaboration on additional management including cultures, antibiotics, and more invasive intervention if necessary.

Late prosthetic hip infection by a hematogenous source can be a serious complication, often requiring extensive hospitalization, intravenous administration of antibiotics, and removal of the hip prosthesis. Eventual reimplantation is done after the infection is eradicated. Currently, there is no consensus for antibiotic prophylaxis before invasive procedures (dental work, colonoscopy). Most surgeons do recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for their patients after THA, but there is no consensus on how long after THA, if not indefinitely, they should have antibiotic prophylaxis.

Iliopsoas impingement can cause significant pain in the otherwise successful THA patient. Typically, the culprit is iatrogenic, from an oversized acetabulum component with anterior overhang, relative retroversion of the components, or protrusion of fixation screws, which results in iliopsoas tendinitis from tendon impingement.