Section 6 Special topics

Childhood and adolescence

Type 1b diabetes has the same clinical presentation as T1aDM, but islet autoantibodies are absent.

The principal aims of treatment of diabetes in childhood are:

• achievement of good metabolic control

• attainment of normal growth and development

Management of diabetes in childhood

Cerebral oedema

• more profound dehydration, hyperventilation and acidosis at presentation

• excessive and rapid fluid administration, especially if initial serum osmolality is greater than 320 mOsm/L

• failure of serum sodium level to rise as hyperglycaemia resolves

• initial IV insulin bolus or too early initiation of insulin infusion.

Insulin therapy

Injection regimens should be individualized and include:

• Basal bolus regimen: 40–60% of the total daily dose as a basal insulin analogue (glargine, detemir) in 1–2 doses a day plus a rapid-acting insulin analogue with each meal (in some patients after the meal); soluble human insulin requires administration at least 20–30 min before each meal

• Intermediate-acting human (or neutral protamine Hagedorm; NPH) insulin twice daily and soluble human insulin 20–30 min before each meal

• Two injections daily of a (pre-mixed) mixture of short or rapid and intermediate-acting insulin before breakfast and before the evening meal

• Three injections using some variation of the following: a mixture of short- or rapid-acting and intermediate-acting insulin before breakfast, rapid-acting or soluble human insulin before the afternoon snack or evening meal, and intermediate or basal/long-acting insulin before bed.

Glargine or detemir insulins should not be mixed with any other insulin.

Paediatric diabetes outpatient care

Diabetes is managed primarily in the outpatient setting by a team including:

Education

• overall health and well-being is assessed

• growth and vital signs are monitored

• routine screening for diabetes-associated complications and comorbidities is performed

The dietitian should review dietary habits and provide ongoing nutrition education as needed.

Diabetes management in school

Sick-day management

• Written instructions are important

• Most parents require telephone advice when first facing sickness in their child and some may need repeated support.

However, infections and other illnesses may be associated with an increase in insulin requirements.

Transition to the adult diabetes clinic

Adolescence is a transitional stage of human development that:

• occurs between childhood and adulthood

• is characterized by significant and complex biological, social and psychological changes.

A powerful predictor of good self-care is self-efficacy. Adolescents should be encouraged to have confidence in their capability to make decisions and take actions that demonstrate good diabetes self-care (see Appendix 6.1: Principles of dietary planning in children with diabetes).

Diabetes in the elderly

Diabetes, mainly type 2 diabetes, is particularly common in the elderly; more than 50% of patients in the UK are over 60 years of age (the majority having type 2 diabetes). In many countries diabetes affects 10–25% of elderly people (> 65 years), with particularly high rates in populations such as Pima Indians, Mexican Americans and South Asians. Glucose tolerance worsens with age, the main factor being impairment of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis in skeletal muscle; progressive insulin resistance also contributes (Table 6.1). Symptoms of diabetes may be non-specific, vague or absent.

Table 6.1 Factors contributing to glucose intolerance in old age

| Impaired glucose disposal and utilization |

|

NIMGU accounts for 70% of glucose uptake under fasting conditions (primarily into the CNS) and for 50% of post-prandial glucose uptake (especially into skeletal muscle) |

Aims of treatment

The management of T2DM and its common comorbidity of cardiovascular disease is complicated because of the added effects of ageing on metabolism and renal function, the use of potentially diabetogenic drugs, and low levels of physical activity. Cardiovascular risk is particularly high because many risk factors of the metabolic syndrome can be present for up to a decade before T2DM is diagnosed. Management strategies for many elderly people with diabetes are the same as those for the younger population, with similar lipid-lowering and antihypertensive treatment schedules, and aspirin or clopidogrel for patients with increased cardiovascular risk. Effective delivery of diabetes care depends on close cooperation between hospital and community, the involvement of diabetes teams and practice nurses, and attention to all causes of disability and ill-health (Table 6.2).

Table 6.2 Special characteristics of older subjects with diabetes

Management of diabetes in women of childbearing age

Pre-pregnancy and pregnancy care

Contraception

Pregnancy should be planned; good contraceptive advice and pre-pregnancy counselling are essential.

Pre-pregnancy targets for blood sugar

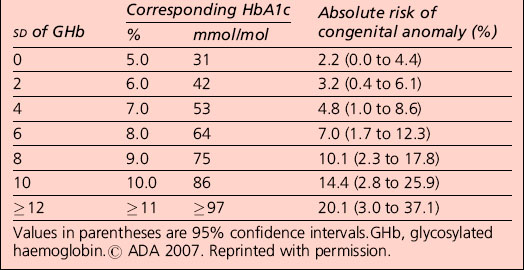

Observational evidence has found an association between maternal glycaemia (before and during pregnancy) and the increased risk of congenital malformation and miscarriage. The risk of congenital anomaly in the offspring of women with pre-pregnancy diabetes is increased with an increasing level of HbA1c. No HbA1c threshold for such effects has been identified (Table 6.3).

Oral medication before and during pregnancy

Nutritional management

It is good clinical practice to provide dietary advice to women before, during and after pregnancy.

Advice on diet and exercise should be offered in line with recommendations for adults with diabetes.

Optimization of glycaemic control

Glucose monitoring

All women with pre-gestational diabetes should be encouraged to achieve excellent glycaemic control.

Complications during pregnancy

Fetal assessment

Screening for GDM

Later pregnancy

Strategies to detect previously existing but undetected diabetes in early pregnancy, and strategies to screen for gestational diabetes at 24–28 weeks, will be refined as information on the characteristics of this testing becomes apparent for the local population. Strategies are likely to be simplified for women believed to be at low risk based on risk factors (Table 6.4).

| BMI > 30 kg/m2 Previous macrosomic baby weighing 4.5 kg or more Previous gestational diabetes Family history of diabetes (first-degree relative with diabetes) Family origin with a high prevalence of diabetes: |

Screening later in pregnancy

All women with risk factors should have a 75-g OGTT at 24–28 weeks.

Fasting plasma glucose at 24–28 weeks is recommended in low-risk women.

Diagnosis of GDM

The adoption of internationally agreed criteria for gestational diabetes using the 75-g OGTT is recommended (Table 6.5):

OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus.

Infants of mothers with diabetes

Specialist advice should be sought if the baby is premature or unwell.

Surgery and diabetes

Anti-insulin effects of surgical stress

Approaches to management

The aims of perioperative management are:

• to avoid hypoglycaemia particularly during anaesthesia

• to avoid excess metabolic decompensation

• to achieve a locally agreed care pathway with which health professionals are familiar.

Insulin-treated patients

Insulin

| Blood glucose level (mmol/L) | Infusion rate (units/h) |

|---|---|

| < 4 | 0 |

| 4.1–7.0 | 1 |

| 7.1–11.0 | 2 |

| 11.1–17.0 | 3 |

| 17.1–22.0 | 4 |

| > 22 | 5 |

Check capillary blood glucose level hourly initially and then 2 hourly.

The glucose–potassium–insulin (GKI) regimen in adults (≥ 16 years of age)

The GKI regimen should be considered in the following situations:

• patients with insulin-requiring diabetes who need surgery

• patients with type 2 diabetes who need major surgery

• patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes who require surgery

• patients with insulin-requiring diabetes who need to fast for procedures (e.g. endoscopy or radiology procedures)

• patients with diabetes who are unable to eat or are nil by mouth (e.g. vomiting due to autonomic neuropathy)

Instructions

1. No subcutaneous insulin to be given on morning of operation or procedure.

2. Prior to setting up the GKI infusion, send blood to the laboratory for urgent glucose and urea and electrolytes and glucose estimation (use an emergency form).

3. Set up the GKI infusion at 8 a.m.:

| 500 mL 10% glucose with 10 mmol KCl (10% glucose and 0.15% potassium chloride IV infusion BP) plus 15 units Actrapid insulin added to bag and mixed well |

To be administered over 5 hours (100 ml/h) |

4. The glucose and insulin infusion must be continued, regardless of whether other IV fluids are required.

5. Subsequent adjustment of the insulin regimen should be as follows:

| Blood glucose result | Action |

|---|---|

| 6–11 mmol/L | Continue infusion as above |

| > 11 mmol/L | Increase insulin concentration by discarding original bag and making up a new bag with 20 units Actrapid added |

| < 6 mmol/L | Decrease the insulin concentration by discarding original bag and making up a new bag with 10 units Actrapid added |

See Section 2, page 87 on adjustment of insulin dose if further dosage change becomes necessary.

Adjustment of insulin dose in GKI regimen

• Measure blood glucose every 2 h initially – frequency of monitoring is variable and depends on the clinical situation; levels can usually be measured less frequently as time progresses.

• Adjust infusion as follows: continue to adjust in 5 units insulin per 500 mL glucose 10% with 10 mmol KCl (1 unit insulin per h) increments/decrements as necessary. However, if moving outwith the range of 10–20 units insulin/500 mL (2–4 units/h) consider the factors listed below before making change.

| Blood glucose result | Action |

|---|---|

| 6–11 mmol/L | Continue usual GKI regimen: 15 units per 500 mL 10% glucose (3 units/h) |

| > 11 mmol/L | Increase to 20 units per 500 mL 10% glucose (4 units/h) |

| < 6 mmol/L | Decrease to 10 units per 500 mL 10% glucose (2 units/h) |

Where target blood glucose levels are not achieved using the above algorithm, consider:

1. The GKI regimen assumes that metabolism is in a steady state. It will work only if the initial blood glucose level was in the target range. It should not be used for patients who are severely hyperglycaemic at the onset (when a separate insulin infusion is better suited), or when they have started to eat again. If the initial blood glucose level is outwith the target range, appropriate measures must be taken to bring it within the range before using the GKI regimen.

2. Check that the IV cannula (Venflon) is patent and functioning, and consider that the GKI solution may have been constituted incorrectly.

3. The constant infusion of glucose at the rate specified is an essential part of the regimen. The insulin regimen cannot be applied when an infusion fluid other than 10% or 5% glucose administered over 5 h is being used (although additional 0.9% sodium chloride can be infused at the same time as 10% glucose when required).

4. In the following situations, altered insulin requirement is likely to occur:

| Condition | Insulin requirement |

|---|---|

| Patients with subcutaneous insulin requirement < 30 units per day; thin elderly type 2 diabetics | May require reduced insulin – start at 10 units per 500-mL bag 10% glucose and 0.15% KCl IV infusion (2 units/h) |

| Obesity | May require increased insulin – start at 15 units per 500-mL bag 10% glucose and 0.15% KCl IV infusion (3 units/h), but be aware of possibility of increased requirement |

| Severe infection | May require increased insulin – may need as much as 25–40 units per 500-mL bag 10% glucose and 0.15% KCl IV infusion (5–8 units/h), or more |

| Any severe illness, infusion of catecholamines or inotropes | Often marked increase in insulin requirement – consider using infusion pump for insulin rather than adding to bag of glucose. Insulin infusion requirement of ≥ 6–12 units/h possible. More frequent monitoring and adjustment required |

| Steroid therapy | May require increased insulin |

5. Insulin-dependent diabetics never require no insulin (other than very transiently). The half-life of IV insulin is approximately 4 min, and that of its biological effect approximately 20 min. The presence of an apparently zero insulin requirement therefore implies a tissue depot of insulin, such as a recent subcutaneous administration of insulin, or persistence of a depot of long-acting insulin (e.g. Lantus®).

Intercurrent illnesses

Type 1 diabetes: sick-day rules

What action should be taken if blood glucose levels are high?

Guidelines

| What action should be taken for a positive ketone test? |

|

• Take extra rapid-acting insulin as soon as possible (see table above). • Drink plenty of water and unsweetened fluids. • Test blood glucose every 1–2 h and repeat the extra insulin (see table above) until blood/urine is negative to ketones. • Try to identify cause of high blood glucose level and seek treatment if necessary. • Contact diabetes team if high glucose and ketone levels persist. • Contact GP/accident and emergency department if you are vomiting, as dehydration may occur. REMEMBER – drink at least a cupful of unsweetened fluid every 15 min (about 500 mL per hour) while blood glucose levels are high. |

Bariatric surgery

Male and female sexual dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction (Tables 6.6–6.9)

Table 6.6 Key features in the clinical history of erectile dysfunction in diabetes

Table 6.7 Medications associated with erectile dysfunction

| Antihypertensives |

(NB: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can cause ejaculatory problems)

Table 6.8 Conditions associated with erectile dysfunction

| Psychological disorders |

| Vascular disorders |

| Neurological disorders |

| Endocrine and metabolic disorders |

| Miscellaneous |

Table 6.9 Investigation of erectile dysfunction in diabetes

| Serum testosterone if libido reduced or hypogonadism suspected (ideally taken at 9 a.m.) Serum prolactin and luteinizing hormone if serum testosterone subnormal Assessment of cardiovascular status if clinically indicated: Glycosylated haemoglobin, serum electrolytes if clinically indicated |

• Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) has a role in endothelium-dependent relaxation of human penile arteries, and this is significantly impaired in penile resistance arteries in men with diabetes.

• The formation of products of non-enzymatic glycosylation to produce advanced glycosylation end-products generates reactive oxygen species that impair NO bioactivity.

• Non-enzymatic glycation of proteins has been reported to impair endothelium-dependent relaxation of aorta in rats.

Erectile dysfunction as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease

There is also evidence that ED is an early marker of endothelial dysfunction.

Cigarette smoking almost doubles the risk of developing ED after about 7 years.

Oral agents

Female sexual dysfunction

Topical oestrogen or simple lubricant gels are usually effective.

Managing loss of libido in women with diabetes is more complex.

Psychosocial and legal aspects

Employment

With a few provisos, diabetes is not a bar to most occupations, and people with diabetes are protected in many countries by legislation against discrimination on the grounds of disability. However, there remains some prejudice against people with diabetes, and access to employment may be limited through discriminatory employment practices and restrictions posed by employers (rather than by legislation). There may be perceived problems associated with diabetes or job-sensitive issues related to the potential risks of hypoglycaemia or visual impairment. Diabetes can also affect employment through increased sick leave and absenteeism, and by adversely influencing productivity. Employment is generally restricted where hypoglycaemia could be hazardous to the worker with diabetes, their colleagues or the general public (Table 6.10). In fact, severe hypoglycaemia in the workplace is uncommon and shift work seldom compromises glycaemic control.

Table 6.10 Forms of employment from which insulin-treated people with diabetes are generally excluded in the UK

| Vocational driving |

Driving

• visual impairment resulting from cataract or retinopathy

• rarely, peripheral neuropathy

• lower limb amputation can present mechanical difficulties with driving – these problems may be overcome by adapting the vehicle and using automatic transmission systems.

Visual impairment

Influence of psychosocial factors on diabetes control

The following factors are associated with poorer control in adults with type 1 diabetes:

Screening for psychological distress

Healthcare professionals should:

• on those occasions where significant psychosocial problems are identified, try to explain the link between these and poorer diabetes control. If possible, it is good practice also to give written information.

• be mindful of the burden caused by psychosocial problems such as clinical and subclinical levels of depression when setting goals and adjusting complex treatment regimens. Patients are less able to make substantial changes to their lives during difficult times.

People with diabetes (or parents/guardians) should:

• try to speak to their general practitioner or diabetes team if they feel they (or their children) have significant psychosocial issues such as those detailed in this section

• be aware that many psychosocial problems make diabetes self-care more difficult, and also that many difficulties can be successfully treated with the right help.

There are no validated tools to screen for eating disorders in people with diabetes.

Effect of psychological interventions on diabetes outcomes

Appendix 6.1 Principles of dietary planning in children with diabetes

1. Eat a well balanced diet, with daily energy intake distributed as follows:

2. If possible, eat meals and snacks at the same time each day.

3. Use snacks to prevent and treat hypoglycaemia (avoid overtreatment):

4. Gauge energy intake to maintain appropriate weight and body mass index:

5. Recommended fibre intake for children older than 1 year: 2.8–3.4 g/MJ; children older than 2 years should eat = (age in years + 5) g fibre/day.

6. Avoid foods high in sodium that may increase the risk of hypertension; target salt intake – to less than 6 g/day.

7. Avoid excessive protein intake.

8. Children with diabetes have the same vitamin and mineral requirements as other healthy children.

9. There is no evidence of harm from an intake of artificial sweeteners in doses not exceeding acceptable daily intakes.

10. Specially labelled diabetic foods are not recommended because they are expensive, unnecessary, often high in fat and may contain sweeteners with laxative effects. These include the sugar alcohols such as sorbitol.

11. Although alcohol intake is generally prohibited in youth, teenagers continue to experiment with and sometimes abuse alcohol. Alcohol may induce prolonged hypoglycaemia in young people with diabetes (up to 16 hours after drinking). Carbohydrate should be eaten before, during and/or after alcohol intake. It may be also necessary to lower the insulin dose, particularly if exercise is performed during or after drinking (e.g. dancing).

12. Approximately 10% of patients with type 1 diabetes have serological evidence of coeliac disease. Those with positive intestinal biopsy or symptomatic have to be treated with a gluten-free diet (GFD). Products derived from wheat, rye, barley and triticale are eliminated and replaced with potato, rice, soy, tapioca, buckwheat and perhaps oats. Most of the children are asymptomatic but the long-term consequences of untreated coeliac autoimmunity appear to warrant a GFD.

Appendix 6.2 Checklist for provision of information to women with GDM

Pre-pregnancy

• Discuss pregnancy planning with women with diabetes of childbearing age at their annual review.

• Advise women with diabetes who are planning pregnancy that they will be referred to a pre-pregnancy multidisciplinary clinic and outline the benefits of multidisciplinary management.

• Provide information on the risks of diabetes to both mother and the fetus.

• Explain why a review of glycaemic control is necessary. Suggest that they should aim for a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level of < 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) for 3 months prior to pregnancy.

• Advise that folic acid 5 mg (available on prescription only) should be taken for 3 months prior to conception and until the end of week 12 of pregnancy.

• Offer lifestyle advice, for example on stopping smoking, alcohol consumption and exercise.

• Explain about the need for a review with the dietitian.

• Explain that a review of all medication will be necessary when planning a pregnancy and offer advice on which medications may need to be stopped, the reasons behind stopping and what the alternatives are.

Pregnancy

• Ensure that the principles of the Keeping Childbirth natural and Dynamic (KCND) initiative are maintained where possible.

• Advise women with diabetes who are pregnant that they will be referred to a joint diabetes antenatal clinic (where available) and outline the benefits of multidisciplinary management.

• Explain that a review of all medication will be necessary when pregnant and offer advice on which medications may need to be stopped, the reasons behind stopping and the alternatives available.

• Advise women about the risks of hypoglycaemia, how to recognize the warning signs and symptoms and what treatment they may require. Ensure they have a glucagon kit and know how and when to use it.

• Advise that during pregnancy tight glycaemic control is necessary and they will need to monitor their blood glucose more often. Be clear about the targets that need to be achieved.

• Offer advice about sick day rules and planning for periods of illness (even minor) that may cause hyperglycaemia. These may include:

• Explain about the need for a review with the dietitian.

• Offer lifestyle advice, for example on stopping smoking, alcohol consumption and exercise.

• Offer advice on safe driving and ensure that women inform the DVLA and their insurance company if they are starting on insulin.

• Inform women about the risk of retinopathy and advise that they will have retinal screening during each trimester. Explain what screening involves and what treatment to expect if retinopathy is found.