CHAPTER 6 Quantitative Acupuncture Evaluation and Clinical Techniques

INTRODUCTION: QUANTITATIVE EVALUATION PREDICTS THE EFFICACY OF ACUPUNCTURE THERAPY

The following clinical example can help us to understand the nature of acupuncture therapy.

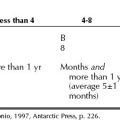

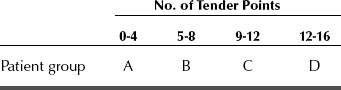

Statistically, patient A represents 28% of the patient population who can completely self-heal; patient B, 34%; patient C, 30% (B and C can partially self-heal); and patient D, 8% (can slowly, or not all, self-heal) (Table 6-1).

QUANTITATIVE ACUPUNCTURE EVALUATION

Thus the number of tender homeostatic acupoints (NHAs; see Chapter 5) shows the interaction between the self-healing potential (HP) and the severity of the symptoms (SS). This relationship can be roughly expressed in the following linear formula:

Dr. H.C. Dung classified patients into four groups (see Table 6-1) according to their self-healing potential and treatment prognosis, after studying more than 15,000 cases.

The selected landmark acupoints for patient evaluation are the H1 deep radial on the forearm (Figures 6-1 and 6-2) and H4 saphenous (Figure 6-3). The deep radial nerve and the saphenous nerve are similar to one another. Both emerge from deep tissues at similar locations just below the elbow and knee and start to branch to innervate other muscles. Figures 6-1 and 6-3 show that more HAs can appear distally to both H1 and H4. These additional points are located along the deep radial and saphenous nerves, about 2 to 3 cm apart. We call these points H1-2, H1-3, H1-4 (located on the deep radial nerve) and H4-2, H4-3, H4-4 (located on the saphenous nerve). Thus the total number of points is 16 bilaterally.

When examining a patient we palpate all these 16 diagnostic points on the forearms and legs on both sides of the body. Using the results of this examination we can classify our patients into four groups, as shown in Table 6-2.

Table 6-2 Classification of Patients According to 16 Evaluation Points (H1−1, −2, −3, −4) + (H4−1, −2, −3, −4)

By combining data from Tables 6-1 and 6-2, we can predict the efficacy, duration, and outcome of acupuncture treatments. Statistical analysis shows that about one third of patients belong to group A (28%). The effects of acupuncture can seem miraculous for this group. Group D accounts for about one tenth of patients (8%), and these are least able to benefit from acupuncture therapy. Most patients, about 64%, belong to groups B and C and represent an average or slightly below average health level. Acupuncture treatments can successfully control chronic pain for patients in groups B and C for some time. In some cases the pain will recur in about 4 to 6 months (see Table 6-1); some patients may enjoy longer pain relief if they take appropriate measures for health maintenance. The mechanism of pain relapse was explained in Chapters 3 and 5. Age and genetic factors may influence the self-healing potential. The age of most group A patients is below 40, and most group D patients are above 60 years of age. Nevertheless it is not uncommon to see older patients in group A and younger patients in group D. We should not assume that older patients are necessarily sick or weak.

The following simple guidelines facilitate the evaluation procedure:

CLINICAL TECHNIQUES

Definition of Efficacy of Acupuncture Treatments

Acupuncture efficacy is measured by (1) the number of treatments needed for maximal relief and (2) the duration of the pain relief. It depends on the interaction between a patient’s self-healing potential and the severity and nature of the symptoms. In Tables 6-1 and 6-2, we classify pain patients into four groups: A, B, C, and D. Accordingly we can classify acupuncture efficacy into four groups: excellent for group A, good for group B, average for group C, and poor for group D. Different groups need a different number of treatments and experience different durations of pain relief.

Collecting Information to Evaluate a Patient’s Healing Potential

Medical History

It is important to collect precise information about any surgical procedures the patient has undergone. Pain symptoms can be more difficult and time consuming to treat when they persist after surgery. This is because surgery alters some of the neuroanatomic structure, whereas acupuncture works best when applied to intact body anatomy.

Syncope or “Needle Fainting”

Dr. Chen, of the Center for Traditional Chinese Medicine of Veterans General Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan, reported 55 syncope events in 28,285 clinical acupuncture visits (0.19%).1 These data are similar to our own clinical evidence. According to Dr. Chen’s statistical analysis, 28,285 visits account for about 3,235 patients, with each patient having an average of eight acupuncture treatments. Thus an acupuncture practitioner may encounter one syncope event in about every 500 treatments; in other words about 2% of patients in an acupuncture clinic will experience syncope. Fortunately syncope, or “needle fainting” as it is called in China, can be predicted and prevented.

Handling Syncope

Prevention of Syncope During Acupuncture Treatment

The following types of patients are more likely to experience syncope, and practitioners should always be prepared when treating patients in these categories:

Pneumothorax

If an acupuncture needle perforates the pulmonary pleura (the serous membrane investing the lungs and lining the chest wall), the needle may cause a local lesion to the pleura or in some cases to the lung. As a result air could penetrate the lesion-damaged tissue of the thoracic wall and accumulate in the pleural cavity, which prevents lung expansion and results in difficult breathing accompanied by chest pain. This condition is called pneumothorax. Special attention to thoracic anatomy is needed (see Chapter 9 and Figure 9-12, p. 137) to avoid pneumothorax when needling points on the anterior, lateral, or posterior thorax.

No medical record exists to indicate that pneumothorax caused by needling has led to a life-threatening condition, but improper acupuncture needling will produce a severe traumatic effect on the patient. If an acupuncture needle perforates the pleura, the patient may suddenly feel pain radiating from the needling site. Usually the patient starts coughing about 30 minutes later and experiences short breaths, pain in the chest area, and tingling or numbness in the arms. When pneumothorax is suspected, the patient should be hospitalized for emergency aid. To prevent pneumothorax, we suggest using needles 25 to 30 mm (about 1 inch) long for paravertebral points (see Chapter 5) and 15 mm long for the lateral and anterior thorax.

When needling acupoints such as the H3 spinal accessory and H13 dorsal scapula (see Chapter 5), we recommend the following procedure: insert a needle (40 mm long) skin deep, and then grasp and hold up the muscle tissue between the fingers and the thumb. After the muscle is raised, continue inserting the needle until it reaches the nodule in the muscle and then immediately withdraw the needle without loosening grasp of the tissue. This safe procedure can be repeated a few times to achieve better muscle relaxation. This needling method should be performed only by experienced practitioners who are familiar with the gross anatomy of this region. Inexperienced practitioners may use an alternative procedure by inserting a few shorter needles (25 mm long) around H3 and H13 to achieve desirable results.

Needling Reaction

Latent Reaction

About 10% of patients feel more pain within 24 or 48 hours after acupuncture treatment. This pain may be “wandering” or appear in a new location. For instance, a patient complaining of lower back pain might experience shoulder pain, knee pain, or a headache for 1 or 2 days after acupuncture treatment.

Needling Skill

We highly recommend using disposable needles with individual guide tubes to minimize any possibility of infection. To insert this type of needle, hold the tube with one hand and lightly and swiftly tap the top of the tube with a finger of the other hand. Subsequently a practitioner can continue to insert the needle by either “pistoning” up and down or rotating clockwise and counterclockwise. These manipulation techniques help to relax the muscle contracture (see Chapter 3) and increase stimulation. Some patients might not tolerate the manipulation and will experience excessive pain, in which case the practitioner should use a finer needle and insert it with minimal twisting or rotating.

Frequency of Acupuncture Appointments

Types of Pain Relief

Three types of recovery are observed:

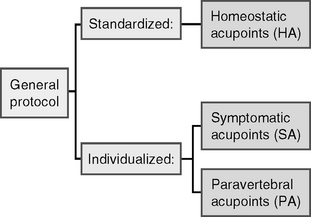

Explanation of the General Protocol

Standardized Protocol for the Prone Position

| Head (2): | H2 great auricular, H7 greater occipital |

| Shoulder bridge (1): | H3 spinal accessory |

| Shoulder (2): | H8 infraspinatus, H13 dorsal scapula |

| Upper back (2): | H20 spinous process of T7, H21 posterior cutaneous of T6 |

| Lower back (3): | H14 superior cluneal, H15 posterior |

Standardized Protocol for Supine Position

| Face (2): | H19 infraorbital, H23 supraorbital |

| Upper limbs (3): | H1 deep radial, H9 lateral antebrachial cutaneous, H12 superficial radial |

| Chest (1): | H17 lateral pectoral |

| Lower limbs (5): | H4 saphenous, H5 deep peroneal, H6 tibial H18 iliotibial, H24 common peroneal |

Individualized Protocol

Locating Symptomatic Acupoints

As explained in Chapter 5, HAs appear in a similar pattern in every patient. Each HA also serves as a “road map” for locating SAs. Finding and treating the right SAs greatly enhances the efficacy of the treatment. The following is an explanation of the general procedure of locating SAs.

Example 1: Locating SAs When Treating “Tennis Elbow”

Practical Application of the General Protocol

Below are examples of how to modify the protocol.

Example 1: Chronic Neck Pain

Evaluation and Prognosis

Clinical Notes

Treatments should be continued until the pain subsides. As more relief is experienced, time between treatments can be extended to 2 to 3 weeks. After maximal relief is achieved, regular maintenance treatments will be needed. The patient should understand that (1) chronic pain may recur even after it appears to have been relieved and (2) regular acupuncture maintenance not only prevents a recurrence but also promotes healthy body function.

Example 3: Chronic Lower Back Pain

Evaluation and Prognosis

Example 4: Shoulder Pain for More Than 6 Months

Evaluation and Prognosis

Repeat the treatment once or twice a week, according to the patient’s condition.

SUMMARY

Based on the number of tender HAs, we can statistically differentiate patients into four types of homeostasis/self-healing potential: 28%, excellent (group A); 34%, good (group B); 30%, average (group C); and 8%, poor (group D). Patients in each group react to acupuncture differently (see Tables 6-1 and 6-2).

The standardized part of the protocol is based on the 24 HAs, and the individualized part includes SAs and PAs. The SAs should be carefully searched for because they appear in different places for every patient. Local HAs provide the “road map” for finding local SAs. The location of SAs is in turn a direct guide to which PAs should be used (segmental mechanism, see Chapters 3 and 5).