CHAPTER 6 PAEDIATRICS

EXAMINATION OF THE NEONATE

Routine examination should include:

6–8-WEEK CHECK

This check is completed by the GP and is combined with the first immunisations. It should include:

NEONATAL JAUNDICE

INFANT FEEDING

BOTTLE-FEEDING

Bottle-fed babies, like breast-fed babies, should be fed on demand and allowed to find their own pattern. Bottles and teats should be sterilised until the baby is >6 months old. Formula milk, as opposed to cow’s milk (which has relatively low iron and vitamin A, C, D and E content), should ideally be given until the baby is 1 year old. The baby requires about 150 ml per kg body weight per day. This is usually given as about six feeds/bottles per day. In the first week or so, the baby takes about 50–70 ml 7–8 times per day.

WEANING

BABIES WITH COLIC

Colic tends to start after 2 weeks of age, and usually settles by 4 months of age. The infant is often well in the morning, but by the evening may be distraught, pale and drawing up its legs. The parents are often quite unable to comfort the baby. They need reassurance that the problem is self-limiting and that they are not at fault since there is no clear cause. Involve the health visitor and encourage the parents to get as much rest as possible. Changing milk formulae is rarely helpful. Breast-feeding technique may need attention. A consistent feeding and sleeping routine may help, as may increased carrying and treatment with e.g. dimethicone (Infacol) 0.5–1 ml before feeds. Be alert for a child at risk (see child protection, p. 99).

CONSTIPATION

CONSTIPATION IN INFANTS

CONSTIPATION AND SOILING IN OLDER CHILDREN

Acute constipation often follows febrile illnesses.

Management

The aim of treatment is to regain the child’s confidence in being able to defaecate painlessly.

NOCTURNAL ENURESIS

Diagnosis

URINARY TRACT INFECTION IN CHILDREN

Management

Follow local guidelines if available:

SLEEP PROBLEMS

Exclude specific problems, e.g. unhappiness, fear, bed-wetting, environmental noise or illness.

Management

Advice

GROWTH PROBLEMS

Growth reflects general health and also the nutritional and emotional environment of a child. (For standard growth charts for girls and boys see appendices, pp. 349–352.)

FAILURE TO THRIVE

If the infant’s growth pattern is causing concern:

SHORT/TALL STATURE

Short stature is considered to be a height below the 3rd centile, tall stature is above the 97th centile (see pp. 349–352). Both are usually normal variants. If there is concern about a child’s height:

A height 8.5 cm above the mean centile is the 97th centile; 8.5 cm below it is the 3rd centile.

RESPIRATORY PROBLEMS

CORYZA

There is rarely any need for antibiotic treatment. Consider paracetamol syrup to reduce irritability, and nasal decongestants if feeding is difficult, e.g. xylometazoline paediatric nasal drops, 2 drops per nostril tds (maximum duration of use 7 days).

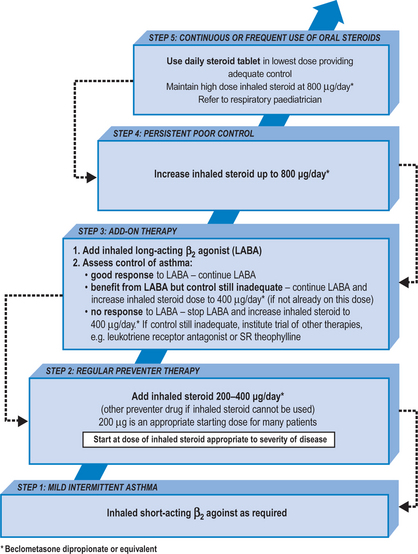

CHRONIC ASTHMA IN CHILDREN UP TO AGE 12

Management of chronic asthma

CONVULSIONS AND SEIZURES

ABSENCE SEIZURES (PETIT MAL EPILEPSY)

During these episodes, the child suddenly ceases activity, and may stare blankly for a period of seconds. The child may seem to be day-dreaming, and the episodes may occur many times per day. Diagnosis relies on witness reports usually from family or school teachers.

Refer to a paediatric neurologist for investigation and management.

NON-FEBRILE CONVULSIONS

CHILD PROTECTION

CHILD PROTECTION PROCEDURES

SUDDEN INFANT DEATH

Management

The management of families suffering a sudden infant death has similarities with other cases of bereavement (see p. 327).