CHAPTER 6. Food for life

June Gordon

Diet and diabetes – from past to present 123

The importance of diet 124

The role of the healthcare professional in providing dietary advice 124

The aims and goals of dietary advice 125

Current dietary recommendations 126

The dietary management of diabetes 131

Carbohydrate management 136

Additional dietary considerations 140

Specific considerations 143

Conclusion 148

References 148

Website addresses 150

Diabetes is one of the oldest diseases known to man and historically diet has been linked with both its cause and cure. For centuries little was known about the disease and the search for a dietary cure relied on trial and error. When it was discovered that the urine of people with diabetes was sweet, it was thought that the diet should be rich in carbohydrate to make up for these urinary losses. An alternative view was that the body could not cope with carbohydrate foods and that they should therefore be avoided.

Dietary advice fluctuated between the two extremes of high-carbohydrate ‘cures’ (based on skimmed milk and oatmeal) to low-carbohydrate diets of meat and boiled vegetables. Even after the discovery of insulin in 1921, carbohydrate restriction was advocated.

Today, diet still plays a central role in the management of diabetes, but the composition has changed considerably and recommendations are now in line with those for a healthy diet for the general population. There are, however, some important differences in emphasis for those with diabetes, which warrant intervention and monitoring to ensure that the nutritional objectives are met.

Diet is an essential component of diabetes management and it is said to be the cornerstone of treatment. For many it is the only form of treatment required. Approximately 80% of people diagnosed will have type 2 diabetes and will be controlled on either diet alone or diet and oral hypoglycaemic agents or diet and insulin therapy. The remaining 20% will have type 1 diabetes and will be controlled on diet and insulin injections. Hence, food choice and eating habits are important aspects of management of diabetes.

THE ROLE OF THE HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL IN PROVIDING DIETARY ADVICE

The clinical standards for diabetes (Clinical Standards Board for Scotland (CSBS) 2001) state that it is desirable that people with diabetes have appropriate access to key personnel, including dieticians. Both the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS; see Chapter 4) and the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT; see Chapter 5) demonstrate the value of dietetic intervention from diagnosis onwards. However, this advice should be part of a comprehensive management plan (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) 2001). The first 3 months from diagnosis have been shown to be vitally important in determining the response to dietary intervention (UKPDS 1990). Given the projected increase in type 2 diabetes, the ideal that dietary information be given only by a diabetes specialist dietician is unlikely to be met (Dyson 2003) and there might be a delay before newly diagnosed individuals have access to a dietician. In these cases, the healthcare professional will be required to give first-line advice. Suitable advice to give to a person newly diagnosed with diabetes is given in Box 6.1.

Box 6.1

Initial dietary advice suitable for a person newly diagnosed with diabetes before his or her appointment with a dietician

▪ Quench thirst with water or sugar-free drinks, e.g. diet lemonades or low-calorie diluting drinks

▪ Have regular meals, avoiding fried or very sugary foods

▪ Eat plenty of vegetables with cereal, bread, pasta, potato, rice or chapatti as the main part of the meal

▪ Have meat, fish, chicken, eggs or pulses as a small part of each meal

Diabetes UK produces general diet information leaflets, which can be useful as first-line advice.

The frequency of visits to a dietician will depend on available resources and local policies and protocols. Some hospital and community dietetic departments produce training packs and run training courses for other healthcare professionals involved in diabetes care. Whatever the situation, it is worth making contact with the local dieticians, as good communication can only benefit the individual as well as ensure consistency of advice. Other healthcare professionals can play a vital role in providing general dietary guidance. They can also reinforce dietetic advice and identify specific situations where more detailed information is required and refer on as appropriate.

THE AIMS AND GOALS OF DIETARY ADVICE

The immediate treatment aim is to control hyperglycaemia; the ultimate aim is to allow the person to lead as normal a life as possible, in good health, and for most people to achieve a weight as close as possible to the ‘ideal’. The overall aims and goals of nutritional advice are summarised in Box 6.2.

Box 6.2

Aims and goals of dietary advice (Diabetes UK 2003)

The aim is to provide those who need advice with the information required to make appropriate choices on the type and quantity of food eaten. The advice must:

▪ Take account of the individual’s personal and cultural preferences, beliefs and lifestyle

▪ Respect the individual’s wishes and willingness to change

▪ Be adapted to the specific needs of the individual, which might change with time and circumstance, e.g. age, pregnancy, nephropathy, intercurrent illness and other illnesses

The beneficial effects of physical activity in the prevention and management of diabetes and the relationship between exercise, energy balance and body weight are an integral part of nutrition counselling. The goals of dietary advice are to:

▪ To maintain or improve health through the use of appropriate and healthy food choices

▪ To achieve and maintain optimal metabolic and physiological outcomes, including:

▪ reduction of risk for microvascular disease by achieving near normal glycaemia without undue risk of hypoglycaemia

▪ reduction of risk for macrovascular disease, including management of body weight, dyslipidaemia and hypertension

▪ To optimise outcomes in diabetic nephropathy and any concomitant disorder such as coeliac disease or cystic fibrosis

BACKGROUND

Before the 1980s, dietary advice centred on carbohydrate restriction as the only means of controlling blood glucose levels. People were advised to limit their intake of carbohydrate foods such as bread, potatoes, rice, pasta and cereals and to fill up on foods such as meat, cheese, eggs, cream and butter. This resulted in a diet low in carbohydrate but high in fat. Research in the 1970s (Brunzell et al 1974, Simpson et al 1979) showed that high-carbohydrate diets could actually improve diabetic control, providing the carbohydrate was in a complex, high-fibre form. Studies were also beginning to show that reducing fat intake in non-diabetic people resulted in reduced morbidity from cardiovascular disease (Miettinen et al 1977). This led researchers to ask whether the high-fat diet could be contributing to the increased risk of heart disease in people with diabetes.

As a result of this research, guidelines were published in both the USA (American Diabetes Association 1979) and the UK (British Diabetic Association Nutrition Subgroup 1982). These overturned decades of teaching by recommending that people with diabetes should consume a diet high in carbohydrate and low in fat. These were considered to be radical documents, but they were followed by the introduction of almost identical policies by diabetes associations in many other countries. These were also very similar to nutritional guidelines published for the general population in the UK (Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) 1984) and by the World Health Organization (James et al, WHO 1988) for Europe. This had positive implications in that people with diabetes were no longer being advised to follow a ‘special diabetic diet’.

These guidelines have now become established practice throughout Europe and North America, although there have been some shifts in emphasis in the light of new knowledge and clinical experience (American Diabetes Association 2003, Diabetes UK Nutrition Subcommittee 2003, European Association for the Study of Diabetes 2000).

CURRENT RECOMMENDATIONS

The current recommendations on the composition of the diet for diabetes are summarised in Table 6.1 and Table 6.2.

| Component | Comment |

|---|---|

| Protein | |

| Not >1 g per kg body weight | |

| Fat | |

| Total fat | <35% of energy intake |

| Saturated + transunsaturated fat | <10% of energy intake |

| N-6 polyunsaturated fat | <10% of energy intake |

| N-3 polyunsaturated fat | Eat fish, especially oily fish, once or twice weekly |

| Fish oil supplements are not recommended | |

| Cis-monounsaturated fat | 10–20% = 60–70% of energy intake |

| Carbohydrate | |

| Total carbohydrate | 45–60% |

| Sucrose | Up to 10% of daily energy provided it is eaten in the context of a healthy diet. Those who are overweight or who have raised blood triglyceride levels should consider using non-nutritive sweeteners where appropriate |

| Fibre | |

| No quantitative recommendation | |

| Soluble fibre | Found in foods such as pulses, oats and fruit |

| Has beneficial effects on glycaemic and lipid metabolism | |

| Insoluble fibre | Found in wholegrain versions of bread, flour and pasta, brown rice and high fibre breakfast cereals |

| Has no direct effects on glycaemic and lipid metabolism but its high satiety content may benefit those trying to lose weight and it is advantageous to gastrointestinal health | |

| Vitamins and antioxidants | |

| Encourage foods naturally rich in vitamins and antioxidants | |

| There is no evidence for the use of supplements and evidence that some are harmful | |

| Salt | |

| <6 g sodium chloride per day | |

| Choice | Comment |

|---|---|

| Nutritive sweeteners: | |

| ▪ Fructose | No proven advantage over sucrose |

| ▪ Sugar alcohols (e.g. sorbitol) |

Lower cariogenic effect but no other advantages over sucrose

May cause diarrhoea

|

| Non-nutritive (artificial/intense) |

Useful in beverages sweeteners

Potentially useful in the overweight

Safe if acceptable daily intake is not exceeded

Heavy users should use a variety of different products

|

| [Diabetic] foods |

Unnecessary, expensive

Can cause diarrhoea

Not recommended

|

| Plant stanols and sterols | Approximately 2 g per day can reduce LDL-cholesterol by 10–15% (see section on dyslipidaemia on p. 146) |

| Fat replacers and substitutes |

Can facilitate weight loss

Long-term studies needed

|

| Herbal preparations | No convincing evidence of benefit |

The main differences in emphasis from previous recommendations (British Diabetic Association Nutrition Subgroup 1992) are:

▪ More flexibility in the proportions of energy from carbohydrate and monounsaturated fat. Monounsaturated fats are promoted as the main source of dietary fat because of their lower atherogenic potential (Kratz et al 2002). Sources of the different types of fatty acids are shown in Table 6.3.

| Type of oil | Example |

|---|---|

| Cis-monounsaturated |

Olive oil

Some rapeseed oils

Fat spreads derived from olive oil

|

| Trans-unsaturated |

Hydrogenated vegetable oils

Hard margarine

Manufactured foods containing hydrogenated vegetable oils (e.g. pies, pastry, biscuits, cakes)

Fat spreads derived from these oils

|

| Polyunsaturated |

N-6

Corn, sunflower

Safflower oil, soya bean oil and seeds

N-3

Oily fish and marine oils

|

▪ More active promotion of carbohydrate foods with a low glycaemic index (GI) (see p. 140).

▪ Greater emphasis on the benefits of regular exercise.

TRANSLATING RECOMMENDATIONS INTO PRACTICAL ADVICE

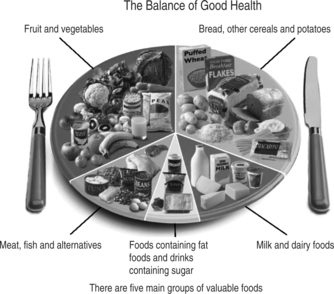

The scientific evidence for the effect of diet on diabetes management needs to be translated into practical and realistic advice for the individual. Because the nutritional objectives for those with diabetes are very similar to those advocated for the entire population, dietary guidance should be based on a framework of healthy eating principles such as the Balance of good health (Health Education Authority (HEA) 1994) shown in Fig. 6.1. More information on this is given in Box 6.3.

|

| Fig. 6.1The balance of good health (HEA 1994).Reproduced with kind permission of the Food Standards Agency |

Box 6.3

The Balance of good health plate model

▪ Primarily a device for encouraging healthy eating practices

▪ A visual method, with the dinner plate serving as a pie chart. This shows the proportions of the plate that should be covered by the various food groups

▪ Simple and adaptable; embodies the principles of healthy eating and promotes memory and understanding through visual methods

▪ Easily implemented in residential and nursing homes

This does not mean, however, that dietary advice is simply a matter of healthy eating guidance; many other issues have to be borne in mind and specific aspects relevant to diabetes will need to be superimposed on this. Table 6.4 shows how it can be adapted for diabetes.

| Food group | Points to emphasise |

|---|---|

|

Bread, cereal foods and potatoes

These should form the largest component of meals and snacks

|

Quantity and timing: these need to remain fairly constant from day to day

Good food choices: pasta, rice, bread, chapattis, potatoes, breakfast cereals (especially oat-based)

Reduce the amount of fat added to these foods

Wholemeal/wholegrain bread and cereals are high in fibre and have advantages in terms of satiety and helping to prevent constipation

|

|

Fruit and vegetables

At least 5 servings of a variety of these foods should be eaten every day

|

These have major health benefits for people with diabetes

1–2 servings of vegetables should be eaten with main meals

More use should be made of fresh fruit as a snack or dessert

Frozen or canned fruits and vegetables are useful alternatives to fresh varieties

Fruit juice should be regarded as a sugar-containing drink and so not consumed on its own – only with meals

Encourage consumption of salad or vegetables with manufactured convenience foods or ready meals

|

| Milk and dairy products 2–3 servings daily |

Low/reduced-fat varieties of milk, yoghurt, fromage frais, etc., should be chosen

Full-fat cheese should be used with care, especially by the overweight; it is best used as part of a meal rather than a snack

Cream should only be used as an occasional treat

|

| Meat, fish, pulses and alternatives 2 servings/day |

Greater use should be made of pulses (peas, beans and lentils), either as an alternative to meat or as a way of making a smaller quantity of meat go further. Fresh, canned or dried pulses are all suitable

Ideally at least 2 portions of fish should be consumed every week, one of which should be oily fish

Fat avoidance is important, e.g. meat should be lean: visible meat fat should be trimmed off after cooking. Consumption of meat products (e.g. burgers, pies, sausage rolls) or high-fat meat mixtures (mince) should be kept to a minimum. Poultry is only a low source of fat if the skin is removed and the fat that appears during cooking is discarded

|

|

Fat-rich and sugar-rich foods

These should be kept to a minimum

|

Sugar-rich foods:

The diet does not have to be sugar free, but sugar-rich confectionary and drinks will impair glycaemic control if consumed at inappropriate times or in addition to meals

Low-calorie [diet] counterparts

Either ordinary jam/marmalade or reduced-sugar varieties can be used in small amounts on bread

Small amounts of sugar-containing biscuits or cakes can be eaten as scheduled snacks, but higher fibre, lower sugar choices are best, e.g. teabreads, fruit cake, English muffins, plain cakes and biscuits. Those who are overweight should be encouraged to make more use of fruit as snacks

Intense artificial sweeteners should be used if sweet-tasting drinks are required

Fat-rich foods:

Sources of fat should be avoided as much as possible

Food should be boiled, baked, grilled, dry roasted or microwaved, but not fried

Minimum amounts of fat should be spread on bread, added to food or used in cooking. Reduced-fat monounsaturated spread and small amounts of monounsaturated oils (olive or rapeseed or canola) are the best choices

High-fat snack foods such as crisps and biscuits should be eaten less often and replaced by healthier alternatives such as fruit, low-fat yoghurt or wholewheat crispbread

|

It takes considerable skill to apply the nutritional objectives of diabetes management in a realistic and practical way. Initially, people should be assessed to determine their willingness to change their dietary behaviour (SIGN 2001). A simple, flexible approach is required and counselling skills should be used to motivate the individual to make positive and achievable dietary changes (see Chapter 3). Not everyone will be able (or willing) to achieve all dietary goals and a balance should be found between what is acceptable, achievable and beneficial to that individual person. For most, the actual target will be to make specific dietary changes in the right direction, i.e. towards the ideal. The nature of these changes will vary according to individual nutritional and clinical priorities, habitual diet and lifestyle and the prevalence of risk factors. The focus should always be on modifying an individual’s existing eating habits (food choice and the timing of its consumption) in a realistic and achievable way. Pre-printed standardised diet sheets alone are of little benefit in modern day diabetes management. The dietary management of diabetes should take place in the stages outlined in Box 6.4.

Box 6.4

Stages in the dietary management of diabetes

▪ Assessment: to decide which aspects of the diet need to be changed and what changes are possible, information will have to be gathered on the person’s background and usual eating habits. Nutritional, personal and clinical information will be relevant in determining the advice given

▪ Education: dietary education is essential to help individuals make the diet and lifestyle changes necessary to optimise diabetic control and long-term health. This cannot be delivered as a single package in a single session. Every one is different in terms of his or her nutritional priorities, dietary targets, pace and degree of change. Education should, therefore, be tailored to the needs of the individual

▪ Monitoring progress: follow-up and review are essential, but the frequency of this will depend on the type of treatment, the person’s ability and confidence, diabetic control and whether or not additional problems such as renal or coeliac disease exist

Approximately 80% of people with type 2 diabetes, and many with type 1 diabetes, are overweight and hence weight loss and stabilisation will be a major priority in their management.

Moderate weight loss of 5–10 kg can help to improve blood glucose and lipid levels, reduce insulin resistance and improve hypertension. It has also been shown that losing weight can improve life expectancy in overweight people with type 2 diabetes by an average of 3–4 months for each 1 kg (2.2 lb) of weight lost (Lean et al 1990). The largest published study to date into weight loss in overweight people with diabetes (Williamson et al 2000) showed that a weight loss of 11% of initial body weight was associated with a reduction in mortality of 25% and in heart disease of 28%. However, losing even small amounts of weight has health benefits. It is therefore worth stressing the benefits of any weight loss and maintenance of this loss for the overweight person with type 2 diabetes.

Assessing body weight and shape

To manage overweight and obesity, it is important to measure and define it in terms of its relative health risk. The body mass index (BMI; Box 6.5) has been adopted widely as the best method of assessing the degree of obesity or overweight.

Box 6.5

Classification of obesity using the body mass index (WHO 1998)

The body mass index (BMI) is calculated by applying the formula:

BMI = Weight (in kilograms) / Height (in metres)2

Weight is without shoes and in indoor clothing, and height is without shoes.

| ▪ ≤ 18.5 | = underweight |

| ▪ 18.5–24.9 | = healthy weight |

| ▪ 25–29.9 | = overweight |

| ▪ 30–39.9 | = moderately obese |

| ▪ >40 | = severely obese |

The ideal range for BMI is, therefore, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2.

Ideally, people with diabetes should have a BMI in the ‘healthy weight’ range, as both diabetes and overweight are risk factors for coronary heart disease. However, BMI does not measure body fat specifically and in recent years there has been a growing interest in the use of waist circumference to determine the risk of obesity (Lean et al 1995). Both diabetes and coronary heart disease are linked with abdominal obesity, where fatty tissue is deposited centrally, giving an apple shape, rather than on the hips and thighs, which gives a pear shape (see Chapter 4). Measuring the waist circumference in addition to BMI can be a useful guide for determining the health risk posed by overweight. Current recommended cut-off points for waist circumference are shown in Table 6.5.

| Substantially increased risk (Caucasian) | Substantially increased risk (Asian) | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | ≥ 102 (40 inches) | ≥ 90 cm (36 inches) |

| Women | ≥ 88 cm (35 inches) | ≥ 80 cm (32 inches) |

The only way to achieve weight loss is to consume less energy than the body needs and, ideally, to increase physical activity. This will incur an energy deficit, body fat stores will be used as an energy source and weight loss will result.

The person with diabetes who is advised to lose weight should, therefore, be given guidance on a reduced energy intake. This should focus primarily on appropriate food choice, with particular emphasis on avoiding fat-rich, energy-dense foods. Changes in food choices should be incorporated into the general healthy eating framework appropriate for diabetes along with any necessary advice on meal pattern and timing. Modification of existing eating habits will be more successful than handing out standardised pre-printed diet sheets.

Dieticians will tailor individual meal plans for the appropriate degree of energy restriction and many will offer training and provide resources for other healthcare professionals to support them in doing the same. Restricting the energy intake by 500 calories per day should produce a weight loss of 0.5 kg per week. In other words, if a person who usually consumes 2000 kcal per day reduces this by 500 kcal daily to 1500 kcal, that person could expect to lose an average of 0.5 kg per week. Weight loss should be gradual, and any weight-reducing programme should be based on realistic expectations of weight loss: 0.5–1 kg (1–2 lb) per week is ideal. Energy intakes of less than 1000 calories per day are not recommended, as they can result in loss of lean body tissue. This will affect metabolic rate and can result in less weight being lost in the long term.

It should be remembered that long-term weight control is the primary objective, so any weight loss should be viewed in a positive light.

Neil is a 54-year-old married man who has just joined the GP practice. His routine medical examination shows that he has glycosuria and subsequent blood tests confirm that he has type 2 diabetes. He is obese and consumes more than 30 units of alcohol per week. He enjoys a fried breakfast at the weekend, takes three teaspoons of sugar in his tea and drinks sugar-containing fizzy drinks. He admits to smoking 40 cigarettes per day and is unemployed.

In the first instance, Neil will require dietary advice alone for treatment management. There is obviously a lot of scope for improving his diet and there are many aspects to tackle. To summarise the key points, Neil:

▪ is obese

▪ probably has a high fat intake

▪ drinks sugar-containing fizzy drinks

▪ smokes

▪ has a high alcohol intake

▪ is unemployed.

The first priority would be to explain in simple terms what diabetes is and why diet is the main element in Neil’s treatment. It is important to emphasise diet and weight loss at this stage and to reinforce this on follow-up. Neil’s wife should be included in all educational sessions and they should be encouraged to discuss modifications of diet together.

Dietary management would be in stages (see Box 6.4) starting with assessment of his current diet and his readiness to change (SIGN 2001). Having completed the assessment, the advice should be broken down into stages so that he is not overwhelmed with information and the prospect of too many aspects of dietary change at once. Not all stages should be covered in the first consultation. Small, gradual changes instead of drastic ones tend to be more acceptable and lead to improved adherence.

Healthy eating

It is important to adopt a psychological approach to promote changes in diet (SIGN 2001) and to emphasise that the diet for diabetes is a healthy diet for all the family:

▪ Advise both Neil and his wife that this healthy way of eating is recommended for the rest of the population and that if they adopt this together they will both receive benefits in terms of reducing the risk of heart disease.

To emphasise that weight loss will help Neil control his diabetes:

▪ Explain that weight loss will only be achieved by reducing the energy content of the diet, but that this does not mean strict ‘dieting’ or starvation.

▪ Agree a realistic target weight with Neil. Use BMI and measure (or ask him to measure) his waist circumference.

▪ Break down the weight loss into small goals to make the ultimate goal seem more achievable.

▪ Offer regular follow-up to give him support and to keep him motivated.

Fat intake

Emphasise the importance of reducing fat intake as follows:

▪ Recommend that both Neil and his wife use alternative methods of cooking breakfast at the weekend, such as grilling, baking, poaching, steaming or microwaving.

▪ Suggest that an ideal breakfast should contain mainly complex carbohydrate (e.g. cereal followed by toast), which Neil might be willing to consider eating on weekdays.

Sugar intake

Reduce sugar intake by:

▪ Suggesting an artificial sweetener as an alternative to sugar and low calorie drinks or water instead of the sucrose-containing ones. Ultimately, Neil might be willing to take tea and coffee without any type of added sweetener.

▪ Assess the frequency of consumption of confectionary and cakes and suggest alternatives.

Smoking

Bear in mind that Neil is a smoker and that to stop smoking will be a very important aspect of his diabetes management. Neil should be encouraged to stop smoking (SIGN 2001) and if he decides that this is his first priority, support him as follows:

▪ Emphasise that to prevent further weight gain would be an appropriate goal at this stage. Weight reduction can be tackled at a later stage once he has stopped smoking.

▪ Point out that Neil might find that he will lose some weight by making changes to his fat and alcohol intake.

Further information on smoking cessation can be found in SIGN 55 (SIGN 2001).

Alcohol intake

To encourage Neil to think about reducing his alcohol intake:

▪ Ask him if he thinks this amount of alcohol is within recommended limits as he currently exceeds this.

▪ Explain that his reported intake of 30 units of alcohol per week equates to at least 2400 calories.

▪ Advise him to avoid the special ‘diabetic’ beers and lagers that have a high alcohol content and to have ordinary beers and lagers or spirits with low calorie mixers in moderation.

▪ Advise him that his excessive alcohol intake will actually make him feel unwell and might cause memory loss (SIGN 2001).

Financial implications

As Neil is unemployed, cost could be a major barrier to dietary change. He can be supported in his efforts by:

▪ Giving practical advice on buying foods that are not more expensive, e.g. fresh fruit and vegetables that are in season and on special offer.

▪ Advising him that he does not need to buy special ‘diabetic’ foods.

▪ Suggesting that he makes the complex carbohydrate food the main part of his meal and has a smaller portion of the more expensive protein foods.

▪ Encouraging him to reduce his alcohol intake and stop smoking.

Neil might be eligible for some of the benefits that are addressed in Chapter 11.

Follow-up

To encourage Neil to make the changes, use a theoretical model with a psychological approach (SIGN 2001):

▪ Offer regular follow-up so that motivation can be sustained and dietary counselling can continue.

▪ Reinforce the advice given by the dietician so that the information Neil receives is consistent.

▪ In consultation with Neil, address each practical step one at a time. Once he has reduced his intake of fried food, replaced the sugar-containing drinks with low-calorie ones and reduced his alcohol intake, consider negotiating an increase in fruit and vegetables, wholemeal bread and wholegrain cereals.

▪ Encourage his wife to support him in the dietary changes and to adopt these for the family as a whole.

▪ Always bear in mind that dietary change can be difficult and may be slow.

Neil’s case study should help to illustrate the stages in the dietary management for him and to give an example of a realistic means of adapting his diet for weight loss.

CARBOHYDRATE MANAGEMENT

Many factors affect the glycaemic response to foods, e.g. the amount and type of carbohydrate consumed, the effects of cooking or processing on food structure and other meal components such as fat and protein.

To maintain blood sugar levels within the acceptable range there has to be a balance between glucose entering the blood from the gastrointestinal tract and the supply of injected or pancreatically produced insulin available. In the person who does not have diabetes, this happens automatically, but in those with diabetes on hypoglycaemic medication (whether it be sulphonylureas or insulin), the situation is different. Once insulin is injected or an oral hypoglycaemic ingested, its hypoglycaemic action will operate whether or not food has been eaten. Hence, if food is not eaten at the usual time or insufficient food is taken, there is a risk that the person will become hypoglycaemic. Equally, consuming large amounts of carbohydrate at times of low activity of the hypoglycaemic agent will result in higher levels of blood glucose than desired. It is therefore vital that there is a balance between carbohydrate intake and hypoglycaemic medication.

Hypoglycaemia cannot occur in people treated by diet alone (or on metformin). In this situation (as in the person who does not have diabetes), insulin is produced when food is eaten. However, because the ability to produce insulin is limited, it is still important to ensure that carbohydrate intake is evenly spread throughout the day and within the body’s ability to handle it.

In practical terms, for people with diabetes, this balance is achieved by regulating the:

▪ meal pattern

▪ amount of carbohydrate consumed

▪ type of carbohydrate consumed.

REGULATING THE MEAL PATTERN

For most people, carbohydrate intake should be fairly evenly distributed throughout the day. Those who have erratic eating habits should be encouraged to adopt a more regular meal pattern to ensure a better and more constant balance between supply and usage of glucose. This can have added benefits in aiding weight loss in those who are overweight. For many, a meal pattern of three evenly sized meals and three snacks is ideal, but this will vary between individuals. Lifestyle might dictate the meal pattern for some and, for people with type 2 diabetes who are overweight, between-meal snacks might need to be discouraged. No matter what, the most important aspect is that the individual’s meal pattern stays relatively constant from day to day. Those who are treated with oral hypoglycaemic agentsor insulin should also be able to adapt their diet for different circumstances, e.g. exercise or illness.

REGULATING THE AMOUNT OF CARBOHYDRATE CONSUMED

Advice is essential so that an adequate carbohydrate intake can be achieved from day to day, especially for those on sulphonylureas or insulin. Traditionally, the amount of carbohydrate was regulated by various different systems, where foods containing a defined amount of carbohydrate were substituted for one another. This allowed individuals to calculate and usually restrict their intake of carbohydrate. Following the realisation in the 1980s that carbohydrate restriction was both unnecessary and counterproductive, simpler methods of meal planning were introduced:

▪ The ‘carbohydrate exchange’ system: this is a system first taught to people more than 30 years ago. People learned the amount of carbohydrate in various foods and how to exchange them for other carbohydrate-containing foods, if desired, to allow variety in the diet while maintaining a fairly consistent carbohydrate intake. For ease of reference, people could eat any type of carbohydrate as long as it was low in sugar and within their set allowance for their meal or snack. Table 6.6 gives some examples of carbohydrate exchanges. The drawbacks of this system are that it does not take into account the glycaemic effect (see p. 139) of a food, nor does it give an indication of protein, fat or energy content, which can draw attention away from these dietary components. The exchange system also tends to result in restriction of carbohydrate, which can result in higher-fat foods being consumed at the expense of carbohydrate.

| Food | Amount supplying 10 g carbohydrate |

|---|---|

| Wholemeal/white bread | 1 small slice |

| Bread roll | Half |

| Digestive biscuits | 1 |

| Apples | 1 |

| Tangerines | 2 |

| Potatoes | 1 egg-sized |

▪ Meal planning and household measures: using this system, advice on meal planning would be given, with emphasis on eating regular meals and snacks; eating a variety of foods; controlling energy intake; using appropriate cooking methods; including foods with a low glycaemic index; encouraging high-fibre, low-fat foods and eating more fruit and vegetables (particularly those containing soluble fibre). The person would be given some quantitative guidance on carbohydrate intake (e.g. the amount typically needed at a main meal, late-night snack or to prevent or treat hypoglycaemia), but grams of carbohydrate would not be mentioned.

It is worth remembering that different approaches will be required for different people in different circumstances and from different cultures. People who have had diabetes for many years might have been taught, and still use, the 10-g carbohydrate exchange system. Although it would be reasonable to encourage them to have a better composition of diet, it can be very disturbing for some to be told to abandon a system that they have used with confidence for many years to manage their diabetes. They should not therefore be forced to change the way in which they do manage the dietary aspects of their diabetes if they do not wish to do so, although many will welcome a more liberal approach.

Some people will feel more comfortable with two fixed daily injections of insulin and a regular meal pattern. Others, by contrast, who are knowledgeable and motivated can, in conjunction with frequent blood glucose monitoring, vary the amount of carbohydrate consumed, or the time at which it is eaten, by adjusting their insulin doses or physical activity or both. In the UK, the results of a trial (DAFNE Study Group 2002) into this liberal approach have been published. This is a 5-day outpatient programme that teaches individuals to adjust their insulin doses to carbohydrate portions by way of carbohydrate to insulin ratio. People are taught to make adjustments on their blood glucose trends associated with food, exercise, alcohol and illness. Although this intensive insulin therapy and carbohydrate counting is time intensive, this style of education helps people understand more about the effects of food on blood glucose levels and be empowered in their self-management (see Chapter 11).

REGULATING THE TYPE OF CARBOHYDRATE: THE GLYCAEMIC INDEX OF FOOD

It used to be thought that if you ate the same amount of carbohydrate – whatever it was – it would have the same effect on your blood glucose levels. It is now known that different carbohydrate-containing foods have different glycaemic responses (Jenkins et al 1984). This means that they have different effects on blood glucose levels, so 10 g of carbohydrate as bread does not have exactly the same effect as 10 g of carbohydrate as fruit or as pasta. Attempts have been made to quantify this effect and to classify foods according to their glycaemic index (GI). This is defined as the glycaemic response to individual foods in relation to that of glucose, i.e. the GI is a measure of how quickly foods containing carbohydrate raise blood glucose levels. Thus choosing slowly absorbed carbohydrates 1can help even-out the blood glucose levels. The glycaemic effect of a carbohydrate food is determined not only by its sugar and fibre content, but also by many physical and chemical characteristics; the way in which an individual food is cooked or processed, or its degree of ripeness, will also affect its GI. The glycaemic response to a single food will also change when it is eaten in combination with other foods, e.g. fat content will delay gastric emptying and therefore delay absorption of carbohydrate; the soluble fibre content of one carbohydrate food will affect the absorption of another. The concept of GI is useful as a pointer to food choice. Foods with consistently low glycaemic effect can be promoted as particularly good choices in preference to those with higher glycaemic potential (Box 6.6). It should be remembered, however, that GI should not be emphasised to such an extent that other important messages concerning meal pattern and overall dietary balance are lost.

Box 6.6

Foods with a low glycaemic index (GI)

These should be promoted as particularly good food choices:

▪ Peas, beans and lentils

▪ Fresh fruit (not over ripe)

▪ Pasta

▪ Barley and basmati rice

▪ Porridge

ORAL HYPOGLYCAEMIC AGENTS

Drugs will be required in the treatment of type 2 diabetes if diet alone fails to control diabetes adequately. Drugs should not, however, be used as an alternative to diet. There are different types of oral hypoglycaemic agents; the modes of action of these are discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

Sulphonylureas and meglitinides

These act by stimulating insulin production (whereas the glitazones enhance the action of insulin). All increase appetite, which can lead to weight gain and deterioration in glycaemic control. People should be made aware of the possible effects of these drugs and appropriate dietary counselling should be available to prevent or minimise weight gain. Although it is beneficial for everyone to eat regularly, it is especially important for those on sulphonylureas, as hypoglycaemia (see Chapter 11, p. 265) can result if meals are missed. For this reason, individuals should also be advised to avoid drinking alcohol on an empty stomach because of the combined hypoglycaemic effects of alcohol and sulphonylureas.

Meglitinides and glitazones

These work for a relatively shorter time, making the risk of hypoglycaemia less. However, people taking these drugs should still be given advice on the causes, recognition and management of hypoglycaemia.

Metformin

This does not act by stimulating insulin production and hence will not cause hypoglycaemia. It is usually the preferred drug for overweight people with type 2 diabetes, as weight gain is a less common side effect than with other oral hypoglycaemics.

Glucosidase inhibitors

These drugs (e.g. acarbose) act as enzyme inhibitors and delay the digestion and absorption of carbohydrate. This has the effect of reducing the rise in blood glucose levels after a meal. They can be useful for overweight individuals because they do not cause an increase in appetite, but they can cause flatulence, diarrhoea and abdominal distension. Glucosidase inhibitors do not cause hypoglycaemia when used as sole therapy, but if hypoglycaemia does occur when it is being used with another agent, then treatment must be with glucose and not sucrose. This is because this drug would prevent the breakdown and absorption of the sucrose into the bloodstream.

Betty is a 67-year-old woman who is overweight (BMI = 29) and has type 2 diabetes that is controlled by diet. She has had deteriorating glycaemic control over the last few months and it is now thought that she needs the addition of an oral hypoglycaemic agent.

There would be various stages to progress through to determine whether an oral hypoglycaemic agent is in fact required:

▪ The first step with Betty would be to review her diet to check whether any changes in meal pattern or food consumption could improve her glycaemic control. She might be inadvertently including foods that are making her blood glucose rise (e.g. drinking unsweetened fruit juice between meals, thinking it is a ‘healthy’ choice). Assessment of her diet and her willingness to make any changes using the information in Table 6.4 would provide useful information as to whether or not there are changes that can be made.

▪ Betty’s recent weight history should be discussed to ascertain whether she has gained weight over the last few months. If this were the case, dietary assessment and subsequent negotiation of dietary targets to facilitate weight loss would be appropriate. Her physical activity should be assessed and any possible increase in this should also be discussed and promoted (SIGN 2001).

▪ The addition of an oral hypoglycaemic agent might be appropriate if there was no improvement in glycaemic control despite the first two steps. Metformin would be the first drug of choice for Betty because it does not tend to increase appetite. Emphasis should be placed on preventing further weight gain by eating an energy-controlled diet and being as physically active as possible.

INSULIN TREATMENT

Type 2 diabetes controlled with insulin

Insulin therapy will be initiated when oral hypoglycaemic agents are insufficient to achieve good glycaemic control (see Chapter 4). Due to the anabolic effect of insulin, weight gain can be a problem. This potential weight gain should be anticipated and explained to the person so that dietary measures can be discussed and instituted. It might be appropriate for some people with type 2 diabetes to combine insulin with metformin, as the latter improves insulin resistance and has an anorectic effect, thereby reducing the insulin dosage required and minimising the anabolic effect (Relimpio et al 1998, Robinson et al 1998).

Balancing food and insulin in type 1 diabetes

The dietary advice that should be given to a person with type 1 diabetes is basically the same as that for a person with type 2 diabetes as the recommendations apply to diabetes per se. Eating regularly is important for people with type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes and is particularly relevant for those people using insulin therapy.

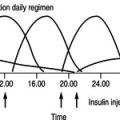

The nature of the insulin regimen has to be considered to ensure that food choice and meal timing are compatible with its hypoglycaemic activity. Many insulin preparations are available, each one having a different speed and duration of activity. They can broadly be categorised into short- or intermediate- and long-acting insulins; these are discussed in detail in Chapter 5. It is important that all members of the diabetes team work with the person with diabetes to choose an insulin and dietary regimen best suited to the individual’s lifestyle.

Many people are maintained on a combination of insulin preparations to optimise blood glucose control. Most are still managed on a combination of a short-acting and intermediate-acting insulin administered twice a day, but there is an increasing use of multiple injection regimens where one dose of long-acting insulin is injected at bedtime to give a continuous background insulin supply and small amounts of short-acting insulin are given via a pen injector before meals during the day. This gives more flexibility in terms of eating habits and is particularly suitable for adolescents and other people with variable lifestyles. As regimens become more flexible, more knowledge is required about the time–action profiles of different insulins and insulin analogues to give appropriate advice about diet. A dietician with experience in diabetes, whether it be at the hospital diabetes centre or within the primary care setting, would usually be responsible for the dietary education of the person in this respect, but all healthcare professionals involved in diabetes care should be aware of the type of advice that might be given. Insulin is anabolic and progressive weight gain can be a problem when glycaemic control is improved or when insulin replaces oral hypoglycaemics in people with type 2 diabetes.

The advent of easy-to-use blood glucose monitoring devices, together with encouraging individuals to take greater control over their own management, has resulted in greater flexibility in insulin administration with people being taught to alter insulin dosage as circumstances dictate. Similar flexibility also applies to diet. Many people learn to adjust their food intake as part of the overall process of achieving tight glycaemic control (see Chapter 11). However, it is important that the overall diet remains appropriate in terms of energy content and balanced in overall composition.

HYPOGLYCAEMIA

Glucose (10–20 g) is the preferred sugar for the immediate treatment of acute hypoglycaemia because it does not require digestion or metabolism. This could be given in the form of 50–100 mL Lucozade or between three and six glucose tablets. After recovery from hypoglycaemia, a further 10–20 g of slower-acting carbohydrate (e.g. two digestive biscuits) should be given, unless the next meal or snack is due, in which case it should be eaten straight away. See Chapter 11 for further explanation on the treatment of hypoglycaemia.

EXERCISE

Regular exercise has positive benefits in that it can lower blood pressure and blood lipids. It can also reduce insulin requirements and improve overall blood glucose control. For overweight individuals with type 2 diabetes, exercise will have the added benefit of increasing energy expenditure, which, when combined with a healthy diet, should assist weight loss. Regular exercise also helps to maintain lean body mass. This prevents the lowering of metabolic rate, which can be a danger with prolonged dieting.

Exercise and hypoglycaemia

Those whose diabetes is controlled by glucose-lowering medication (whether sulphonylureas, meglitinides or insulin) should be given advice on the prevention of hypoglycaemia during and after exercise (SIGN 2001). Exercise can affect blood glucose levels in two main ways:

1. If a person’s blood glucose control is poor and there is insufficient insulin, adrenaline will be released as a result of the exercise and will make the blood glucose rise.

2. If a person’s blood glucose is reasonably well controlled this usually implies that there is an adequate supply of insulin. Here the main concern is hypoglycaemia as a result of exercise.

To avoid hypoglycaemia, extra carbohydrate should be taken before the activity. Alternatively, the dosage of insulin or sulphonylurea can be reduced, but care needs to be taken not to reduce this too much. This will be discussed on an individual basis. The amount of extra carbohydrate required will depend on the individual and the type of exercise undertaken. It can be taken as part of the last meal before exercise (e.g. an extra 20 g of complex carbohydrate as digestive biscuits, fruit, yoghurt or nuts and raisins) or as a quick snack immediately before (e.g. 20 g of quicker-acting carbohydrate in the form of a small bar of chocolate). Top-ups of carbohydrate might be required for endurance exercises to prevent hypoglycaemia during the exercise. Extra carbohydrate might also be required after exercising has stopped due to the fact that the hypoglycaemic effect of exercise can last for several hours. It is also worth remembering that everyday activities such as running for the bus or vigorous housework can also cause hypoglycaemia.

ALCOHOL

There is no need for the person with diabetes to avoid alcohol completely, but it can create additional hazards. Alcohol consumption should be restricted to 3–4 units per day in men and 2–3 units per day in women, as in the general population (SIGN 2001). Alcohol can act as a very potent hypoglycaemic agent because it inhibits the formation of glucose by the liver. Glucose-lowering agents (e.g. sulphonylureas or insulin) together with alcohol can have a very serious effect if inadequate carbohydrate is eaten. Delayed hypoglycaemia can occur up to 16 hours after alcohol consumption – a fact that must be emphasised. People should avoid drinking alcohol on an empty stomach and ensure that they have extra carbohydrate to make up for the added hypoglycaemic effect of the alcohol. It is especially important to have a bedtime snack, as alcohol can continue to lower the blood glucose for several hours after alcohol consumption has stopped. Signs of hypoglycaemia can resemble signs of drunkenness; so that alcohol can mask the symptoms, which can therefore go unnoticed. Hence it is also vital that individuals carry identification that they have diabetes.

ILLNESS

Any illness can affect diabetic control. Individuals taking insulin or tablets must continue with these when ill (see Chapter 11). If people are vomiting they should contact their GP, but insulin must never be stopped. The body’s natural response to illness is to utilise more glucose. Insulin requirements rise and there is an increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis. This means that increased doses of insulin or oral hypoglycaemics might be required. Carbohydrate must also be taken in some form and meals can be replaced with liquid, semi-solid or solid foods containing carbohydrate depending on the person’s appetite. As a guide, 10 g of carbohydrate should be taken every hour until the person feels better. Regular blood testing is essential in times of illness. Table 6.7 suggests some sources of carbohydrate during illness.

| Food | Amount supplying 10 g carbohydrate |

|---|---|

| Lucozade | 50 mL/2 fl oz |

| Fruit juice | 1 small glass (100 mL/4 fl oz) |

| Milk | 1 cup (200 mL) |

| Thick soup | 1 cup (200 mL) |

| Ice cream | 1 briquette (1 scoop) |

| Yoghurt | Half tub low fat/1 tub ‘diet’ |

FASTING FOR RELIGIOUS FESTIVALS

During the month of Ramadan, practising Muslims abstain from food and liquids between dawn and sunset, commonly eating one large evening meal after sunset and a light meal before dawn. Fasting is obligatory for all healthy adult Muslims, although people with diabetes are exempt from fasting. Despite this, many choose to observe this religious obligation. Fasting can last up to 18 hours a day during the summer months and large quantities of sugary fluids, such as canned juices and fizzy drinks, together with fried foods and carbohydrate-rich meals are taken during the non-fasting hours. Sweet foods may also be specially prepared for Ramadan. Longer gaps between meals and greater amounts of foods (in particular foods high in sugar and starch) mean that people with diabetes can experience large swings in blood glucose levels during Ramadan.

Amina is a 56-year-old Muslim woman with type 1 diabetes that is controlled on a twice-daily mix of soluble and intermediate-acting insulin. She asks for advice with regard to her diet and insulin during the period of Ramadan. Although she is aware that she is exempt from fasting, she is choosing to observe this religious obligation.

With the appropriate advice, Amina should be able to undertake the fast safely. Ideally, discussions should take place well in advance of Ramadan as clinic attendance often drops at this time because people avoid exercise to conserve energy. Amina should be encouraged to attend the clinic to discuss monitoring her diabetes with the healthcare team and to be given advice about any changes to her insulin regime. Appointments should not be scheduled for days that she wishes to visit the mosque. Amina should be encouraged to take her blood glucose regularly because she will be at risk of hypoglycaemia. Some Muslims consider blood glucose testing as breaking a fast; however, an educational class designed specifically for self-management during Ramadan explains that this is a myth (Chowdhury et al 2003). Meal times should be discussed to ascertain the exact changes from Amina’s current meal pattern and some general dietary guidelines given:

▪ limit the amount of sweet foods taken after sunset, e.g. only have small amounts of ladoo, jelaibi or burfi

▪ fill up on starchy foods such as basmati rice, chapati or naan

▪ include fruits, vegetables, dhal and yoghurt in the meals after sunset and in the early morning

▪ choose water and sugar-free drinks to quench thirst. Avoid adding sugar to drinks and use a sweetener where needed

▪ limit fried foods such as paratha, puri, samosas, chevera, pakoras, katlamas, fried kebabs and Bombay mix. Measure the amount of oil used in cooking (between one and two tablespoons for a four-person dish).

Amina will also require advice about insulin. The most important message is for her not to stop taking insulin during Ramadan. She would need guidance on how to make appropriate adjustments to her insulin dosage and to negotiate for how long she can safely fast. There are some general guidelines regarding insulin:

▪ Her insulin could be changed to isophane alone before her morning meal and soluble mixed with a small dose of isophane in the evening. It is strongly recommended that premixed insulins are avoided during fasting, but if the person insists on staying on this, the dose should be changed so that less insulin is given at Sehri (the early morning meal).

▪ It might be useful to change her onto an insulin analogue as this would allow her to eat immediately after injecting. It is also short acting, which would reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia when fasting.

▪ She should be advised where possible to rest during the day to avoid low blood glucose levels.

It would be useful to ask:

▪ Have you fasted before with diabetes? What happened then? Valuable information can be obtained from past experience.

▪ Will you have the pre-fast meal in the morning or do you plan to omit this meal?

▪ Are you prepared to break the fast if you become hypoglycaemic and need sugar? It is recommended that people break their fast if they become hypoglycaemic.

With the appropriate support and guidance, the period of Ramadan should not pose a risk to the person with diabetes (www.diabetes/org.uk/healthcare).

DYSLIPIDAEMIA (RAISED BLOOD LIPID LEVELS)

Altered lipid metabolism occurs in people with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes but the pattern of dyslipidaemia is different. It is often present in people newly diagnosed with diabetes or those with poor glycaemic control. People’s lipid profiles should be reassessed after there has been control of hyperglycaemia. In people with type 1 diabetes with adequate control, lipid profiles tend to be similar to those of the non-diabetic population [elevated total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol; see Chapter 8]. As the risk of cardiovascular disease is higher in the population of people with diabetes, it is more important that these elevated levels are detected and corrected, ideally by means of dietary adjustment.

Most people with type 2 diabetes, and some overweight people with type 1 diabetes, have a dyslipidaemia associated with insulin resistance. This is characterised by an increase in triglyceride and harmful LDL cholesterol and a reduction in protective high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. This often persists after glycaemic control has been achieved. Lifestyle interventions include weight loss, particularly by reduction of saturated fat (which reduces concentrations of triglyceride, LDL cholesterol and may increase HDL cholesterol). If weight loss is not required, energy from saturated fat can be replaced by carbohydrate or cis-monounsaturated fat. Regular physical exercise will help to reduce triglyceride concentrations and to improve insulin sensitivity. Sterols and stanols of plant origin have been shown to lower LDL cholesterol. These are now being incorporated into spreads and other fat-derived products such as yoghurts, semi-skimmed milk, etc., and are marketed as adjuncts to other dietary methods of reducing LDL cholesterol. However, they are very expensive (two to four times more than conventional) and their long-term effects on morbidity and mortality due to coronary heart disease are unknown. Hypertriglyceridaemia is sometimes associated with alcohol consumption and this possibility should always be considered. Fish oil supplements should not be recommended because of potential deleterious effects on LDL cholesterol and glycaemic control (Franz et al 2002).

COELIAC DISEASE

People with type 1 diabetes have a greater risk of developing coeliac disease than the general population, possibly as a result of the presence of HLA-related autoimmune factors common to both conditions (Cronin & Shanahan 1997). Because of this, coeliac disease should be suspected in anyone with diabetes with gastrointestinal symptoms or unexplained anaemia. Coeliac disease is characterised by intolerance to gluten, a protein found in wheat and rye and to similar proteins found in barley and possibly oats. The reaction to gluten damages the mucosal lining of the small intestine, flattening the villi and reducing the ability to absorb nutrients. As a result, symptoms of malabsorption commonly occur, although these can vary in nature and severity. The intolerance is permanent and requires complete and life-long exclusion of gluten from the diet. This not only corrects the histological and clinical consequences but also reduces the risk of long-term detrimental effects on health.

Belinda is a 35-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes who presents to her GP with a history of fatigue and unexplained iron-deficiency anaemia. She undergoes blood tests and an intestinal biopsy and is subsequently found to have coeliac disease.

Belinda will need to be referred to a dietician for detailed advice about commencing on a strict gluten-free diet. This is a major undertaking in itself, as it will place a double dietary burden on someone who already has diabetes and it is vital that she receives good dietetic support. There will be additional constraints on food choices many of which are key dietary sources of carbohydrate, such as bread, pasta, breakfast cereals, biscuits and many other manufactured foods. When coeliac disease is untreated, there is an increased risk of hypoglycaemia, and the introduction of a gluten-free diet results in an increase in insulin requirement (Iafusco et al 1998). There should be good liaison within the diabetes team to ensure that the appropriate support and advice is given. Dietetic guidance will be essential to ensure that Belinda’s carbohydrate intake is not compromised and that she has appropriate information on avoiding gluten, how to make alternative food choices (such as rice and potatoes) or how to make substitutes in foods (such as specially manufactured gluten-free breads, flours and pasta). It will also be necessary to ensure that Belinda has a balanced diet to maintain health and protect against disease, particularly osteoporosis. She should have regular dietetic follow-up to encourage adherence with thegluten-free diet. The difficulties in following a gluten-free diet, both in terms of family meals and eating away from home, should not be underestimated.

Diet is the cornerstone of treatment for diabetes. Nutritional recommendations have changed over the years in the light of new scientific evidence available and are now similar to those for healthy eating for the rest of the population. This still represents a significant deviation from the typical UK diet and many people with diabetes consider diet to be the most difficult and traumatic part of management. All members of the healthcare team should be aware of the current nutritional guidelines for diabetes to ensure that consistent information is given to individuals and the positive aspects of dietary change emphasised. Regular follow-up and support will be vital to encourage the individuals and their families to make the necessary changes. If the whole family is supportive and prepared to make changes towards better eating habits, it can help the individual person follow the appropriate dietary advice. Diabetes should be seen as the catalyst for change, which can ultimately improve the future health of the whole family.

REFERENCES

American Diabetes Association (ADA), Principles of nutrition and dietary recommendations for individuals with diabetes mellitus, Diabetes 28 (1979) 1027–1030.

American Diabetes Association (ADA), Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Position statement, Diabetes Care 26 (2003) S51–S61.

British Diabetic Association (BDA) Nutrition Subcommittee, Dietary recommendations for diabetics for the 1980s, Human Nutrition: Applied Nutrition 36A (1982) 378–394 .

British Diabetic Association (BDA) Nutrition Subcommittee, Dietary recommendations for people with diabetes: an update for the 1990s, Diabetic Medicine 9 (2) (1992) 189–202.

JD Brunzell, RL Lerner, D Porte, et al., Effect of a fat-free high carbohydrate diet on diabetic subjects with fasting hyperglycaemia, Diabetes 23 (1974) 138–142.

TA Chowdhury, HA Hussain, M Hayes, An educational class on diabetes self-management during Ramadan, Practical Diabetes International 20 (8) (2003) 306–308.

Clinical Standards Board for Scotland (CSBS), Clinical standards diabetes. (2001) CSBS, Edinburgh .

C Cronin, F Shanahan, Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and coeliac disease, Lancet 349 (1997) 1096–1097.

DAFNE Study Group, Training in flexible, intensive insulin management to enable dietary freedom in people with type 1 diabetes: dose adjustment for normal eating (DAFNE) randomized controlled trial, British Medical Journal 325 (2002) 746–749.

Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy (COMA), Diet and cardiovascular disease. Report on health and social subjects 28. (1984) HMSO, London .

Diabetes UK Nutrition Subcommittee, The implementation of dietary advice for people with diabetes, Diabetic Medicine 20 (2003) 786–807.

P Dyson, The role of nutrition in diabetes, Nursing Standard 17 (51) (2003) 47–53.

European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Diabetes and Nutrition Study Group, Recommendations for the nutritional management of patients with diabetes mellitus, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 54 (2000) 353–355.

MJ Franz, JP Bantle, CA Beebe, et al., Evidence based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications, Diabetes Care 25 (2002) 148–198.

Health Education Authority (HEA), The balance of good health. Introducing the National Food Guide. (1994) HEA, London .

D Iafusco, F Rea, F Prisco, Hypo and reduction of the insulin requirement as a sign of coeliac disease in children with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, Diabetes Care 21 (8) (1998) 1379–1380.

WPT James, A Ferro-Luzzi, B Izaksson, et al., Healthy nutrition. (1988) World Health Organization, Copenhagen ; WHO Regional Publications No 24..

DJA Jenkins, TMS Wolever, AL Jenkins, et al., The glycaemic response to carbohydrate foods, Lancet 2 (1984) 388–391.

M Kratz, P Cullen, F Kannenberg, et al., Effects of dietary fatty acids on the composition and oxidizability of low density lipoprotein, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 56 (2002) 72–81.

MEJ Lean, JK Powrie, AS Anderson, et al., Obesity, weight loss and prognosis in type 2 diabetes, Diabetic Medicine 7 (1990) 228–233.

MJ Lean, TS Han, CE Morrison, Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management, British Medical Journal 311 (1995) 158–161.

M Miettinen, O Turpeinen, MN Karvonen, et al., Cholesterol-lowering diet and mortality from coronary heart disease, Lancet 2 (1977) 1418–1419.

F Relimpio, A Pumar, MA Losada Mangas, et al., Adding metformin versus insulin dose increase in insulin-treated but poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: an open-label randomized trial, Diabetic Medicine 15 (1998) 997–1002.

AC Robinson, J Burke, S Robinson, et al., The effects of metformin on glycaemic control and serum lipids in insulin treated NIDDM patients with suboptimal metabolic control, Diabetes Care 21 (1998) 701–705.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), SIGN 55: management of diabetes. (2001) SIGN, Edinburgh .

RW Simpson, JI Mann, J Eaton, et al., High-carbohydrate diets and insulin dependent diabetes, British Medical Journal 2 (1979) 523–525.

In: (Editor: B Thomas) Manual of Dietetic Practice 3rd edn. (2001) Blackwell Science, UK.

United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes (UKPDS) Study Group, Response of fasting plasma glucose to diet therapy in newly presenting type 2 diabetic patients (UKPDS 7), Metabolism 39 (1990) 905–912.

DE Williamson, TJ Thompson, M Thun, et al., Intentional weight loss and mortality among overweight individuals with diabetes, Diabetes Care 23 (2000) 1499–1504.

WEBSITE ADDRESSES

British Dietetic Association: www.bda.uk.com

Clinical Standards: can be accessed via: www.show.scot.nhs.uk/organisations/orgindex.htm

Coeliac Society: www.coeliac.co.uk

Diabetes UK: www.diabetes.org.uk

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines: www.sign.ac.uk