IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM

Policy problems addressed through federal–state relations in health usually centre on ‘fiscal squabbles’, ‘waiting’ and ‘waste’. ‘Fiscal squabbles’ break out between different levels of government when one level tries to shift costs to another or, alternatively, seeks to minimise its contributions to funding health services. Much of the politics and negotiation between the federal and state governments involves deciding who has fiscal responsibility for various health functions and programs and then developing mechanisms to ensure that each level of government meets its agreed responsibilities for funding.

‘Waiting’ drives much of the politics of health. The public, through the media, is primarily concerned about access to services (particularly acute hospital services). As Kingdon has stressed, indicators frequently identify problems requiring policy intervention (Kingdon 1984). When indicators of access suggest services are unavailable, unaffordable, very distant or require a long wait governments come under pressure. Not surprisingly, professional groups and service providers often fuel these debates. Given the Australian and state governments share responsibility for service provision, they then share responsibility for criticisms over access to services. As with cost shifting, there is a tendency for each level of government to blame the other for access problems. In addition to the fiscal rules, health agreements between the Australian and state governments often have a heavy emphasis on defining responsibilities for demand and access to services.

‘Waste’ is a proxy for inefficiency, fragmentation and duplication in the delivery of health programs. At its worst, this leads to significant concerns about quality. Often discontinuity and conflict between the Australian and state governments is blamed for poor health outcomes and inefficient use of resources. A significant drive to improve the productivity, quality and effectiveness of the health system underpins inter-governmental negotiations.

In this chapter we approach analysis of these policy problems by focusing on how inter-governmental relationships within the federal system affect the design and implementation of particular health programs. It is our view that coordination across programs and the boundaries between them is the most fruitful area of analysis in addressing the problems we have briefly outlined above.

However, before moving to a more detailed discussion of program coordination and boundaries and policy options for addressing them, we need to consider how federal and state government responsibilities are distributed and what mechanisms have been put in place to manage federal–state relationships.

THE CURRENT DISTRIBUTION OF FEDERAL AND STATE GOVERNMENT RESPONSIBILITIES

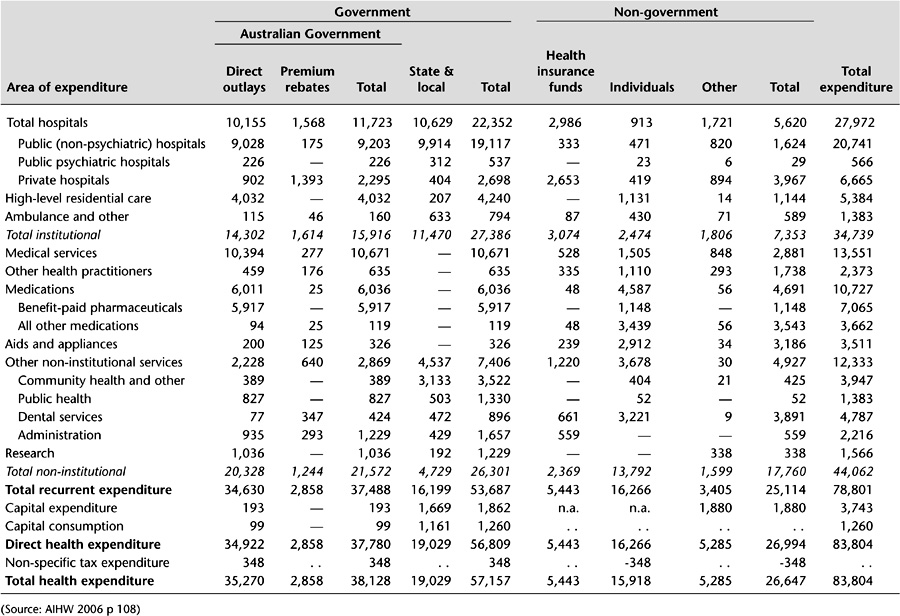

In Australia, total health expenditure has grown rapidly over the past decade. In constant prices, expenditure has increased by $31 billion and 1.7% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the decade from 1994–95 to $87.5 billion and 9.8% of GDP in 2004–05. Estimated health expenditure was $4319 per person, up from $2797 10 years earlier (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2006).

Table 6.1 shows the distribution of health expenditure for different areas of activity for 2004–05. Of the total, 42% went to hospitals and residential care. Non-institutional services made up 53% of total expenditure. Only 1.5% was spent on public health programs to promote health and prevent illness and disease.

Table 6.1 Total health expenditure, constant prices, Australia, by area of expenditure and source of funds, 2004–05 ($million)

The Australian government is by far the most significant funder of health services. In 2004–05, the federal government provided 45.6% of the funding, states and territories 22.6%, individuals (out-of-pocket expenditure) 19%, health insurance 6.5% and other non-government sources (including injury compensation agencies) 6.3% (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2006). These shares are unevenly distributed across programs.

The federal government has primary responsibility for funding primary and specialist medical services through the Medicare program. In practice, the states and the Australian government jointly regulate medical services through registration bodies and the policy and compliance provisions of the Medicare program. Inpatient and outpatient medical services in public hospitals are the responsibility of the states. The federal government provides a Medicare subsidy for medical services provided in private hospitals.

The states are primarily responsible for providing a range of public health, primary health, and community care services, including maternal and child health, school health, community health, mental health, and alcohol and drug services. More recently, the Australian government has augmented these primary care services through Medicare and by directly funding non-government agencies for allied health services.

The federal and state governments jointly fund home and community care for frail older people and younger people with disabilities through the Home and Community Care (HACC) Agreements and the Commonwealth State Disability Agreements. The states are primarily responsible for the operation of the services covered by these agreements, although the Australian government retains responsibility for providing employment services for younger people with disabilities.

While in Australia government provides the majority of funding for most mainstream health programs and services, this is not the case for oral health. Individuals pay the majority of the costs of these services themselves. The states provide limited public oral health programs for children and low-income adults. Almost no funds for public oral health services are provided from federal sources.

The Australian government has the major responsibility for funding the provision of pharmaceuticals in primary and community care settings, and meets the lion’s share of pharmaceutical expenditure (85% for prescribed medications). Pharmaceuticals are provided to consumers through the Pharmaceuticals Benefits Scheme (PBS) with a mandatory co-payment and a safety net where total annual expenditure exceeds preset limits. Safety and quality of pharmaceutical products and other therapeutic goods are managed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Pricing by pharmaceutical companies is regulated through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC). States are responsible for the provision of inpatient pharmaceuticals in public hospitals with some exceptions for highly specialised drugs. Responsibility for funding outpatient pharmaceuticals in public hospitals varies between the states. The Australian government, consumers and health insurers have joint responsibility for funding pharmaceuticals in private hospitals.

The states have primary responsibility for operating and regulating public hospitals. Funding is provided jointly by the federal and state governments through the Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCA). These 5-year, bilateral agreements are designed to provide universal, free public hospital care on the basis of clinical need to all Australians, regardless of location. They set the national framework for public hospital services.

The federal and state governments have very different emphases in terms of their respective expenditure patterns. Public hospitals and community and public health services are the main objects of state government expenditure: these two items together account for almost three-quarters of their health expenditure. The main objects of federal government expenditure are medical benefits (28% of its funding), public hospitals (25%), pharmaceutical benefits (16%), and high-level residential care (nursing homes, 11%). This different expenditure pattern leads to different emphases in policy focus and attention, discussed further below.

Australian and state government funding, regulation and operation of health programs is a mosaic of overlapping and blurred boundaries. Much of this reflects the history of federal–state relationships through Australia’s unique form of federalism. The next section outlines the institutions of Australian federalism.

POLICY RESPONSES: THE INSTITUTIONS OF FEDERALISM

The Constitution

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia (Parliament of Australia 1987), drafted last century, defined the relationship between the national government and the states to limit the powers of the former and to make these powers difficult to change. Where the Australian government had powers, it was intended that these should prevail over the powers of the states. But the states retained sovereignty over areas where the national government had no jurisdiction. Unlike the United Kingdom, where the national parliament is able to resolve constitutional questions, in Australia the High Court was established as the vehicle for adjudicating in disputes about the powers of the Australian government, thereby inevitably placing the High Court in a quasi political and legislative role (Davis et al. 1988).

As economic and social pressure on the Australian state has become more complex, the federal government has progressively sought to extend its powers. Section 96 of the Constitution gives it power to provide general and specific purpose payments to the states as it sees fit. In order to exercise that power it must have the fiscal wherewithal to force the states to the table. It achieved this by restricting state borrowing powers through establishing the Loans Council in 1927 and by its acquisition of universal income tax powers in 1942 (Rydon 1989). The Australian government has progressively gathered significantly more revenue than it spends for its own purposes, while the converse is true for the states – a situation known as ‘vertical fiscal imbalance’.

The states have therefore become dependent on the Australian government for specific-purpose payments made through federal–state agreements to provide services. In health and related areas these include the Australian Health Care Agreements, the HACC Agreements and the Commonwealth State Disability Agreements. In 1999 an Intergovernmental Agreement on the Reform of Commonwealth–State Financial Relations established a Goods and Services Tax (GST) implemented federally to provide the states with a revenue stream. Funds from the GST flow to the states on the basis of relativities determined by the Commonwealth Grants Commission. The GST is a growth tax which largely replaces previous financial assistance grants made by the national government to the states. It also places a set of specific state government taxes. In part, the intention of the GST is to provide a more certain fiscal environment for state governments.

Notwithstanding the introduction of the GST, the own-purpose expenditure of the states continues to exceed their own-purpose revenue. Currently, it would be difficult for the states to replace federal government contributions in major agreements, such as the AHCA and HACC, from their own revenue streams. Therefore they have only limited ability to resist the national government’s fiscal directives in health-related Special Purpose Payments (SPPs).

The Australian government’s powers have been increased through judicial decisions and constitutional referendums. While referendums have generally been unsuccessful, two of the eight that have been carried since federation were vital for extending the federal government’s ability to develop national social policy. The most important of these, the creation of section 51xxiiiA in 1946, allowed for:

the provision of maternity allowances, widows’ pensions, child endowment, unemployment, pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services (but not so as to authorise any form of civil conscription), benefits to students and family allowances.

In the second case, the successful 1967 referendum to amend section 51xxvi allowed the Australian government to make laws for Aboriginal people.

High Court decisions

As Rydon notes, the Constitution is not clearly worded and there is considerable scope for interpretation (Rydon 1995). As a result, in a number of cases High Court decisions have also extended the federal government’s powers to make laws in relation to social programs. For example, the Australian government has been able to use the external affairs power to enter into international agreements and then legislate and create programs in areas where previously it had no direct powers.

In combination with the original constitutional powers over quarantine, marriage and divorce, invalid and old-age pensions, immigration and emigration and ‘the influx of criminals’, these new powers form the basis for the Australian government’s ability to create and administer its own social programs. As well, section 96 gives the Australian government power ‘to grant financial assistance to any state on such terms and conditions as the Parliament thinks fit’. This section has formed the basis for gaining state agreement to federal government policy objectives where the national government’s powers are absent or difficult to exercise for practical or political reasons. It has been particularly used to circumvent the constitutional limitation on the nationalisation of key sectors of social and economic activity which is set out in section 92.

Most recently the Australian government has won a major extension of its powers when the High Court decided in relation to Workplace Relations Case (Roth & Griffith 2006) that the national government has a broad power to regulate foreign, trading or financial corporations. Many health institutions, particularly public hospitals and larger community health agencies, are corporations and the federal government therefore appears to have the power to regulate any aspect of what they do.

Nevertheless, although the Australian government’s power has grown, its dominance is not absolute and constitutional ambiguity and the interpretative powers of the High Court ensures an inherently flexible, emerging and contested relationship between the federal government and the states. For many important areas of national social and economic policy, the Australian government requires the agreement of the states to achieve change. Moreover, in a number of cases, where the constitution gives neither level of government dominance, dual systems of federal and state administration, funding and provision have developed. In the face of changing social and economic conditions federalism is continually being reinvented. Not surprisingly, a number of coordinating and negotiation structures have arisen to deal with these uncertainties.

Federal–state councils

Most importantly, federal, state and territory heads of government meet annually (since 1992 called the Council of Australian Governments, COAG) to consider a range of federal–state matters of national importance. In 1999, the Ministerial Council for Commonwealth–State Financial Relations (Treasurers Conference) was established as part of the Intergovernmental Agreement to Reform Commonwealth–State Financial Relations. The council considers overall fiscal policy, revenue shares and federal payments to the states and territories, including the GST and SPPs.

Similarly federal, state and territory portfolio ministers meet annually as ministerial councils to consider specific policy issues. In this respect, for example, the Australian health ministers’ and community services ministers’ councils are central to the resolution of national policy disputes regarding the development of specific social programs such as those which relate to continuing care services for people with psychiatric illness, frail older people and those with disabilities.

Given its constitutional limitations, which necessarily fragment legislative and administrative responsibilities for significant social and economic functions across levels of government, the national government is forced to negotiate with the states and territories through these forums when it wants to initiate major reform proposals which cross-jurisdictional boundaries. While the Australian government is able to wield significant fiscal power and use its national voice in direct appeals through electoral processes, the states and territories nevertheless have significant capacity to frustrate the federal government by refusing to cooperate. Clearly when differing political parties are in government at the national and state levels, particularly in the most populous eastern seaboard states, these problems are accentuated.

The previous sections have outlined the broad context for understanding federalism and health. However, the issues come alive for health consumers when they try to access particular services. The way services operate is determined by the programs which each level of government provides. Programs are the currency for discussing federal–state relations in health. Both levels of government organise their funding, regulation and direct provision of services through programs. Programs have goals, objectives, funding and accountability mechanisms, guidelines and regulations. As outlined above, the Australian federation ensures that each level of government has sovereignty in the way it designs its programs. The problems of federation (and the actual experience of consumers) are then the problems of program boundaries and coordination.

PROGRAM BOUNDARIES AND COORDINATION

Program boundaries are an inevitable consequence of public sector program design. In order to ensure appropriate parliamentary accountability of expenditure, programmatic rules need to be developed to determine what services will be funded, what people will be eligible, and in the case of ‘special appropriations’, rules also need to be developed about how much will be paid for each service or product. These rules inevitably create problems at the margin. With income-support schemes, rules can create poverty traps and very high effective marginal rates of taxation if a low-income person earns additional income. Service delivery programs create equivalent gaps and perverse incentives and so it is not possible to design a service system with no problems of service coordination and transitions across boundaries. The quixotic quest for a perfectly coordinated system ignores the service reality: strengthening some interrelationships necessarily weakens others. Strong coordination of community and inpatient mental health services inevitably implies weaker links between community mental health and generalist community services and between inpatient psychiatry and other inpatient services. As Leutz paraphrased Abraham Lincoln: ‘You can integrate some services for all of the people or all services for some of the people but you can’t integrate all services for all of the people’ (Leutz 1999).

But this is not to say that policy should not attempt to minimise the perverse impact of program boundaries. Programmatic boundary issues can be characterised as being of two kinds:

These programmatic discontinuities can cause problems in terms of continuity of care or efficiency, and can be schematically represented (see Table 6.2).

|

Table 6.2 Examples of problems of programmatic boundary alignment |

||

| System attribute affected | Programmatic discontinuity | |

|---|---|---|

| Silos and cliffs | Price at the margin for substitutes | |

| Continuity of care | Failures of MBS chronic disease design | Long stay in hospital–residential care interface |

| Efficiency | Workforce | Hospital outpatient–specialist rooms interface |

Of course, program boundaries can create problems for service delivery even in unitary countries such as the United Kingdom (Pritchard & Hughes 1995) and where a single level of government has sole responsibility. For example, the Australian government is responsible for residential aged care and its direct substitutes and has a number of tightly designed programs to fulfil this responsibility. Two such programs, known by their acronyms EACH (Extended Aged Care at Home) and CACP (Community Aged Care Package), provide support in the community for people assessed as requiring residential aged care. There is a significant gap in the level of support provided under the two programs, whereas support needs vary as a continuous function. This dichotomous nature of the design of support programs and their relative availability creates a programmatic discontinuity in a program area in which the federal government has sole responsibility. But an additional layer of complexity is involved when there are multiple players because of the creation of externalities, if costs fall on the payer but the benefits fall on the other level of government or other participants in the policy area.

Table 6.2 provides four examples of alignment problems caused by programmatic discontinuities associated with federalism. The first row, identifying problems associated with continuity of care, is becoming increasingly important. In a system characterised by chronic disease, the patient journey crosses a number of different funding programs. At each programmatic boundary, problems of continuity of care can emerge, exacerbating handover problems associated with institutional provision.

The example used in the table relating to chronic disease is one of missed opportunities. From a state government perspective, managing the increasing costs of chronic disease requires a significant investment in prevention programs. But the key to enhancing investment rests with changing the behaviour of medical practitioners, the levers for which are in the hands of national government through its responsibility for the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). The benefits of better designed chronic disease programs fall in part on the Australian government (through reduced use of medical and pharmaceutical services) but also significantly on state governments through reduced use of hospital services. The Australian government may emphasise that significant benefits fall on states, reducing its incentive to redesign the MBS arrangements to reflect the contemporary reality of chronic disease. This is all the more important because of the economics of the Medicare Schedule: the time of medical practitioners is limited and the cost of incentive payments to redirect medical practitioner time from one activity to another is thus quite low. In contrast, for the state to design an incentive program to apply to medical practitioners, it would need to create an infrastructure for paying doctors and it would face the full costs of any programmatic design.

A second example of problems in terms of patient flow is the second cell in the first row of the table. People in need of long stay care can be accommodated in either residential aged care facilities, provision of which is funded and rationed by the Australian government, or they can occupy a hospital bed after the conclusion of an acute stay episode. Because the services are substitutes, failure to provide adequate residential aged care will cause a backup of people inappropriately accommodated in acute hospital beds. Here the federal government makes the savings from under-provision and the costs fall on the state government through its provision of hospital services. The political and economic costs of backup of patients in acute wards falls on states, the benefits of reduced expenditure falls on the Australian government.

Other examples of programmatic discontinuity occur in terms of realisation of the efficiency goal of public sector management. Two examples are provided in the table, one of problems of programmatic silos and one of pricing at the margin.

The Australian government has a large degree of control over workforce supply through its control of immigration and the university sector. But the cost of tight supply controls fall in part on state governments through an inability to staff public hospitals.

The second example relates to specialist outpatient services in public hospitals funded by state governments and specialist services in the community funded through the MBS, clear service substitutes. Anomalies in the AHCAs mean that a service provided to the same patient seen by the same clinician for the same condition in the same building can be characterised as being provided in four different ways:

2. by a ‘privatised’ clinic where services are bulk-billed and subsidised by the hospital

4. by a pre-1998 clinic which cannot be privatised under the AHCA.

The absurdity of this arrangement is patently obvious; it is made more absurd because record keeping of what are pre-1998 and post-1998 services is relatively unclear (Auditor-General 2007). Assuming that a local hospital is committed to providing access to ambulatory specialist services, there is strong incentive on the hospital to have those services provided through the uncapped fully federally funded Medicare arrangements rather then through state government funding arrangements (which may only have weak incentives for outpatient provision given the typically poor recording in this sector).

These problems of programmatic discontinuity are also affected by problems of programmatic design. The principal objects of direct federal government expenditure are through the MBS, the PBS, health insurance subsidies and residential aged care. In contrast, state government’s principal objects of expenditure are for hospitals, community healthcare and prevention. These different foci of expenditure tend to create a similar set of foci of policy interventions. The concept of bounded rationality advanced by Lindblom (1958) is relevant here. Managers cannot be totally ‘synoptic’ and so they tend to limit their consideration of policy options to ones that emphasise incremental change to existing programs. Thus state officials addressing problems of chronic disease might tend to focus on community health provision rather than involvement of general practitioners.

For similar reasons, there is a tendency towards ‘programmatic isomorphism’ programs at a single level of government tending to evolve to look similar in basic design. The vast bulk of federal government expenditure is allocated through payments to private sector (and non-government sector) agents: Medicare to doctors, pharmaceutical payments to pharmacists, residential aged care payments to residential aged care facilities, subsidies to health insurance. The states are much more involved in direct service delivery. Governments thus tend to develop new programs (or change old programs) in ways that align with the dominant provision type of the relevant government. All of this means that states and the Australian government approach the health system with very different eyes and very different inclinations in terms of program design. This in turn means that programmatic alignment can be quite difficult.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR POLICY DEVELOPMENT

But what are the solutions? In terms of the column relating to pricing at the margin, solutions should be to reduce or eliminate the incentives in these substitute programs. In the case of residential aged care and long stay hospital care, the incentive would be eliminated if the federal government had responsibility for both residential aged care and long stay patients in hospitals. Similarly with hospital outpatient and specialist services, the Australian government could easily assume responsibility for both types of provision, a policy direction which appears to be supported by current Health Minister Tony Abbott.

The problems of silos and cliffs are somewhat more complex. Two broad groups of solutions have been articulated: clearer functional separation and the alternative, closer cooperative action.

Functional separation

There are three main approaches to functional separation: capitated fund holding, jurisdictional realignment and addressing perverse incentives.

Capitated fund holding

Capitated fund holding addresses boundary problems by creating new, integrated organisations assuming responsibility for what was previously the responsibility of both levels of government. It is the most dramatic of the functional separation approaches as effectively both levels of government have diminished roles in healthcare. In the most extreme version of the proposal, the capitated organisations are privatised and the role of government becomes simply a funder.

Two versions of capitated fund holding have been proposed: competitive and non-competitive. The competitive model is exemplified by Scotton’s suggestions for managed competition (1999). He has proposed that the federal government fund a single program of adjusted capitation grants for a comprehensive range of healthcare to competing budget holders. Budget holders would compete for consumers who elect to enrol with them on the basis of the services and co-payment arrangements they offer. Budget holders would contract with a range of public and private providers to provide healthcare services. Providers would therefore compete to develop contracts with fundholders. In Scotton’s model the states would have responsibility for providing public health services and supervising and underwriting regionally based budget holders. Managed competition has a number of inherent significant challenges. These include the difficulties of combining existing programs, realigning federal and state responsibilities, developing contractual rules for providers and designing risk adjusted capitation models that do not lead to adverse selection. The risks and costs associated with these changes are high for relatively unquantifiable benefits. Large scale, managed competition is therefore unlikely to be adopted in Australia (Productivity Commission 2002).

Alternatively, various proposals for non-competitive enrolment with budget holders have been developed (Segal et al. 2002). In non-competitive models consumers would be enrolled with a budget holder based on residence. Budget holders would have responsibility for the health of geographically defined populations. Ensuring efficiency is a major issue for non-competitive models. Regulation by government rather than competition is proposed to achieve efficiency. The Australian government would retain broad responsibility for the overall distribution of funds to ensure national equity and efficiency. The states or the national government could have responsibility for managing the performance of regional fundholders and health providers.

Jurisdictional realignment

There have been two major realignments in federal–state responsibility for health in the past 60 years. Both have seen the progressive increase in the Australian government powers in relation to the provision of health services. The first occurred during the period of the Curtin–Chifley Labor Governments that saw the amendment to section 51xxiiiA of the Constitution to allow the Australian government to make payments for health services. Only the pharmaceutical benefits component of the Chifley Government’s social insurance scheme for health was introduced at the time but this constitutional change significantly altered the balance of federal–state powers over health.

The second major realignment occurred during the first half of the 1970s when, building on the Chifley Government’s policies, the Whitlam Government introduced the Medibank program, including the federal–state hospital financing agreements. Doing so gave the Australian government a much more significant role in providing health services than had previously been the case under the largely state government and private health insurance model which had prevailed. Although structural arrangements introduced by Whitlam were substantially wound back by the Fraser Government, they were again strengthened by the Hawke Government in the 1980s and have largely remained intact until the present period.

More recently there have been proposals that the national government should take over greater responsibility for public hospitals. The most concrete of these was the Medicare Gold policy proposed by the Labor Opposition at the 2004 election. This would have seen the Australian government take over responsibility for all public and private hospital funding for people aged 75 and over.

Most recently, the Howard Government has developed a strategy of ‘national localism’ which bypasses state governments to directly fund local agencies, including hospitals, health services and local government. The most spectacular example was the Commonwealth’s promise of direct funding for Mersey Hospital in Tasmania, following a decision by the Tasmanian State Government to rationalise specialist services between Burnie and Devonport. The Howard Government sought to capitalise on community opposition to the plan in the context of a looming Federal election by promising to establish and fund a community trust to run the hospital. In doing so, the Commonwealth rode roughshod over protracted state planning and consultation process without any consultation with the state government. Subsequently, the Prime Minister sought to justify these actions by appeals to the critical protection of local community interests over the need for a wider analysis of costs and benefits. Significant concerns about safety, quality and practicality of the proposed arrangement were deemed irrelevant. What is interesting is that, for ill or for good, the Commonwealth is now clearly expanding its propensity to act in areas that were previously the province of the states. The Tasmanian State Government capitulated shortly after the Commonwealth’s decision and agreed to treat the Mersey Hospital as a private facility funded by the Commonwealth and to redirect its funding to other services. Nor do the states have much capacity to optimise the financial outcomes when the Commonwealth chooses to act capriciously. Despite the state’s protestations, it is highly likely that the Commonwealth has the power to adjust Commonwealth health funding to Tasmania to take account of its direct contribution to the Mersey.

Addressing perverse incentives

As argued above, boundary problems associated with perverse price or ‘cost-shifting’ incentives for substitutes can be ameliorated by boundary realignment and shifting responsibility from one level of government to another.

Strengths and weaknesses of functional separation options

The health sector is large, representing a significant share of the budgets of both the federal and state governments. Healthcare is high on political agendas. A consequence of this is that achieving major functional realignment involves major fiscal and political responsibility realignment, with fiscal and political winners and losers. (The concept of ‘political winner’ here is complex: gaining additional political responsibilities is not necessarily desirable if the responsibility brings with it accountability for a politically difficult and resource-hungry sector like health.) Functional realignment (other than at the margin to address clear perverse incentives) is thus hard and, as history has shown, relatively rare.

Our judgment is that transition and implementation difficulties consign major functional realignment to the basket of ‘neat and tidy but unlikely’ reform solutions. But there is significant scope for program realignment at the margins. This might, for example, see the federal government take full responsibility for primary care services, including state-run community health services.

Improved cooperative action

Improved cooperative action is hard to argue against and proposals to end bickering and ‘blame-shifting’ by working more cooperatively are advanced regularly. Three broad classes of such proposals are advanced: development of new joint governance arrangements; better benefit sharing; and clearer national policy and goal setting. These proposals are not mutually exclusive.

Joint governance

Recently Menadue (2004) has proposed the establishment of a joint national federal–state ‘health commission’. Joint commissions would be state-based with up to six (excluding the territories) commissions, each varying in their approach. Each commission would share responsibility for funding and governance between the national government and the states. Funds for all major programs would be pooled at the state level on an agreed formula. The commission would then purchase health services from existing public and private health providers.

Softer options along the same lines involve more (or better) cooperative structures. Here one could see bilateral federal–state ministerial councils established in each state to structure formal coordination and exchange locally. Bilateral ministerial councils could be charged with identifying local opportunities for service improvement, specific barriers to implementation and potential joint action to address these.

Better benefit sharing

As argued above, Australia’s federated structure, with responsibility for healthcare shared by two levels of government, creates an overlay of potential externalities to the complexity of program design. Formal benefit sharing is designed to address this by facilitating introduction of initiatives where the benefits and costs fall unequally by developing mechanisms to reallocate the benefits appropriately (or equally). Formalisation of these proposals was incorporated in the 1998–2003 AHCAs that stipulated that:

The Commonwealth and Victoria2 will consider proposals which move funding for specific services between Commonwealth and State funded programs on the basis that each proposal meets the following criteria:

- The proposal must be consistent with accepted evidence-based best practice care models.

- There should be a sound basis for believing that the reform will lead to improved patient outcomes and/or more cost-effective care.

- The impact of the proposal should be measurable in terms of change in services delivered and costs to the health system as a whole and to each party to this Agreement.

- If the proposal is expected to lead to net savings these should be shared equitably between the Commonwealth and Victoria.

- The proposal should have potential to be replicated on a scale such that extension can be realistically tested and be evaluated in terms of such extension; and

- The proposal must preserve eligible persons’ current access to Medicare Benefits Schedule services or their equivalent.

- Reform proposals may result in cashing out of State funded programs and/or Commonwealth funded programs, including the Medicare Benefits Schedule and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

- There should be a sound basis for believing that the reform will lead to improved patient outcomes and/or more cost-effective care.

These ‘measure and share’ provisions were dropped from the subsequent 2003–2008 agreements, perhaps because they were not, in the end, utilised.

Clearer national policy and goal setting

Cooperative action could be enhanced if there were clarity and agreement about goals (and targets) that provided sufficient clarity as to give clear guides for action. This thinking underlies regular calls for a ‘national health policy’ or similar to provide such a road map. But developing a clear strategy is challenging in the face of differing political priorities (and complexions), achieving agreement often requires some vagueness to provide latitude for different parties to give different interpretations or priorities. The vaguer and more encompassing the language, the less a policy will provide any real guide to action.

National policy might also be developed by the Australian government alone. Under this scenario, the Australian government might assume the role of articulating goals and standards and use its financial powers to obtain state sign-up. The Australian government (or a quasiindependent agency such as the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW]) might then publish tracking reports to benchmark and compare performance. The federal government has assumed this role under the current AHCA.3 ‘Competitive federalism’ and local political pressure then become levers to improve services and outcomes in the different states.

A variant of the policy and goal setting approach is for the Australian government to develop more clearly as a ‘purchaser’ of services. Under this approach, the federal government would become more explicit in articulating desired outcomes of its investments and funding and allow states more autonomy in the means to achieve these outcomes. Such an approach would require specifying targets in terms of outcomes (Duckett & Swerissen 1996) and the ability to define the ‘products’ being purchased (Ashton 1998).

Strengths and weaknesses of cooperative action options

Cooperative action proposals have little political salience: it is hard to get public support or interest about more opportunities for bureaucrats to talk to each other! But one clear example of federal–state cooperative action was the coordinated care trials that involved testing a hypothesis that elimination of programmatic boundaries would either improve continuity of care or efficiency. Both federal and state action was required to effect these trials. Recent COAG decisions about health workforce were designed to ameliorate the problems of program discontinuity in this area with creation of federal–state committees to facilitate joint planning of health workforce needs.

Cooperative action requires both levels of government to commit to real action: giving up individual power in favour of shared power and negotiating additional funding or funding flexibility from central agencies. Neither component of this is easy, and the benefits of cooperative action may in the end prove illusory, hard to document or accruing after the initiators have moved on. Thus, despite the logic and superficial appeal of such proposals, there have been few documented successes of these arrangements.

CONCLUSION

We have argued that the policy problems governments try to address through federal–state negotiations are best thought of as the problems of aligning and coordinating programs. While ‘big bang’ solutions to realignment are attractive to policy spectators, they are unlikely to be adopted. Health will never be integrated into one program which is the responsibility of one level of government.

Addressing the ‘fiscal squabbles’, ‘waiting’ and ‘waste’ we alluded to at the beginning of this chapter will require the Australian government and the states to consider strategies for functional alignment and cooperative action in relation to specific programs.