CHAPTER 6 Diagnostic Rating Scales and Psychiatric Instruments

OVERVIEW

However, in some settings, the MSE alone is insufficient to collect a complete inventory of patient symptoms or to yield a unifying diagnosis. For example, if a psychotic patient has symptoms of avolition, flat affect, and social withdrawal, it might be difficult to determine (from the standard diagnostic interview alone) whether this pattern reflects negative symptoms, co-morbid depression, or medication-induced akinesia.1 At other times, performing a MSE may not be an efficient use of time or resources to achieve the desired clinical goal: imagine how many fewer patients might be identified during depression screening days if the lengthy, full MSE were the screening instrument of choice.2 Finally, the subjective nature of the MSE often renders it prohibitive in research studies, in which multiple clinicians may be assessing subjects; without the use of an objective, reliable diagnostic tool, subjects may be inadequately or incorrectly categorized, generating results that are difficult to interpret and from which it is difficult to generalize.3

By using diagnostic rating scales, clinicians can obtain objective, and sometimes quantifiable, information about a patient’s symptoms in settings where the traditional MSE is either inadequate or inappropriate. Rating scales may serve as an adjunct to the diagnostic interview, or as stand-alone measures (as in research or screening milieus). These instruments are as versatile as they are varied, and can be used to aid in symptom assessment, diagnosis, treatment planning, or treatment monitoring. In this chapter, an overview of many of the psychiatric diagnostic rating scales used in clinical care and research is provided (Table 6-1). Information on how to acquire copies of the rating scales discussed in this chapter is available in the Appendix.

| General Ratings | |

| SCID-I and SCID-CV | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Diagnosis |

| MINI | Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview |

| SCAN | Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry |

| GAF | Global Assessment of Function Scale |

| CGI | Clinical Global Impressions Scale |

| Mood Disorders | |

| HAM-D | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| IDS | Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology |

| Zung SDS | Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale |

| HANDS | Harvard Department of Psychiatry National Depression Screening Day Scale |

| MSRS | Manic State Rating Scale |

| Y-MRS | Young Mania Rating Scale |

| Psychotic Disorders | |

| PANSS | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale |

| BPRS | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale |

| SAPS | Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms |

| SANS | Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms |

| SDS | Schedule of the Deficit Syndrome |

| AIMS | Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale |

| BARS | Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale |

| EPS | Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effects Scale |

| Anxiety Disorders | |

| HAM-A | Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| Y-BOCS | Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale |

| BSPS | Brief Social Phobia Scale |

| CAPS | Clinician Administered PTSD Scale |

| Substance Abuse Disorders | |

| CAGE | CAGE questionnaire |

| MAST | Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test |

| DAST | Drug Abuse Screening Test |

| FTND | Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence |

| Cognitive Disorders | |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| CDT | Clock Drawing Test |

| DRS | Dementia Rating Scale |

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THE SELECTION OF DIAGNOSTIC RATING SCALES

How “good” is a given diagnostic rating scale? Will it measure what the clinician wants it to measure, and will it do so consistently? How much time and expense will it require to administer? These questions are important to consider regardless of which diagnostic ratings scale is used, and in what setting. Before describing the various ratings scales in detail, several factors important to evaluating rating scale design and implementation will be considered (Table 6-2).

| Reliability | For a given subject, are the results consistent across different evaluators, test conditions, and test times? |

| Validity | Does the instrument truly measure what it is intended to measure? How well does it compare to the gold standard? |

| Sensitivity | If the disorder is present, how likely is it that the test is positive? |

| Specificity | If the disorder is absent, how likely is it that the test is negative? |

| Positive predictive value | If the test is positive, how likely is it that the disorder is present? |

| Negative predictive value | If the test is negative, how likely is it that the disorder is absent? |

| Cost- and time-effectiveness | Does the instrument provide accurate results in a timely and inexpensive way? |

| Administration | Are ratings determined by the patient or the evaluator? What are the advantages and disadvantages of this approach? |

| Training requirements | What degree of expertise is required for valid and reliable measurements to occur? |

Recall that for this patient, though, negative symptoms constituted only one possible etiology for her current presentation. If the underlying problem truly reflected a co-morbid depression, and not negative symptoms, a valid negative symptom rating scale would indicate a low score, and a valid depression rating scale would yield a high score. The validity of a rating scale concerns whether it correctly detects the true underlying condition. In this case, the negative symptom scale produced a true negative result, and the depression scale produced a true positive result (Table 6-3). However, if the negative symptom scale had indicated a high score, a type 1 error would have occurred, and the patient may have been incorrectly diagnosed with negative symptoms. Conversely, if the depression scale produced a low score, a type 2 error will have led the clinician to miss the correct diagnosis of depression. The related measures of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value (defined in Table 6-2 and illustrated in Table 6-3) can provide estimates of a diagnostic rating scale’s validity, especially in comparison to “gold standard” tests.

Table 6-3 Validity Calculations

| Disorder Present | Disorder Not Present | |

|---|---|---|

| Test positive | A (true positive) | B (type 1 error) |

| Test negative | C (type 2 error) | D (true negative) |

Sensitivity = A/(A + C)

Specificity = D/(B + D)

Positive predictive value = A/(A + B) Negative predictive value = D/(C + D)

False-positive rate = 1 minus positive predictive value

False-negative rate = 1 minus negative predictive value

Several important logistical factors also come into play when evaluating the usefulness of a diagnostic test. Certain rating scales are freely available, whereas others may be obtained only from the author or publisher at a cost. Briefer instruments require less time to administer, which can be essential if large numbers of patients must be screened, but they may be less sensitive or specific than longer instruments and lead to more diagnostic errors. Some rating scales may be self-administered by the patient, reducing the possibility of observer bias; however, such ratings can be compromised in patients with significant behavioral or cognitive impairments. Alternatively, clinician-administered rating scales tend to be more valid and reliable than self-rated scales, but they also tend to require more time and, in some cases, specialized training for the rater. A final consideration is the cultural context of the patient (and the rater): culture-specific conceptions of psychiatric illness can profoundly influence the report and interpretation of specific symptoms and the assignment of a diagnosis. The relative importance of these factors depends on the specific clinical or research milieu, and each factor must be carefully weighed to guide the selection of an optimal rating instrument.4,5

GENERAL DIAGNOSTIC INSTRUMENTS

One of the most frequently used general instruments is the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Diagnosis (SCID-I). The SCID-I is a lengthy, semistructured survey of psychiatric illness across multiple domains (Table 6-4). An introductory segment uses open-ended questions to assess demographics, as well as medical, psychiatric, and medication use histories. The subsequent modules ask specific questions about diagnostic criteria, taken from the DSM-IV, in nine different realms of psychopathology. Within these modules, responses are generally rated as “present,” “absent (or subthreshold),” or “inadequate information”; scores are tallied to determine likely diagnoses. The SCID-I can take several hours to administer, although in some instances, raters use only portions of the SCID that relate to clinical or research areas of interest. An abbreviated version, the SCID-CV (Clinical Version), includes simplified modules and assesses the most common clinical diagnoses.

Table 6-4 Domains of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Diagnosis (SCID)

| I. | Overview section |

| II. | Mood episodes |

| III. | Psychotic symptoms |

| IV. | Psychotic disorders differential |

| V. | Mood disorders differential |

| VI. | Substance use |

| VII. | Anxiety disorders |

| VIII. | Somatoform disorders |

| IX. | Eating disorders |

| X. | Adjustment disorders |

A third general interview, the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN), focuses less directly on DSM-IV categories and provides a broader assessment of psychosocial function (Table 6-5). The SCAN evolved from the older Present State Examination, which covers several categories of psychopathology, but also includes sections for collateral history, developmental issues, personality dis-orders, and social impairment. However, like the SCID-I, the SCAN can be time consuming, and administration requires familiarity with its format. While the SCAN provides a more complete history in certain respects, it does not lend itself to making a DSM-IV diagnosis in as linear a fashion as does the SCID-I and the MINI.

Table 6-5 Components of the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN)

| I. Present State Examination |

| Part I: Demographic information; medical history; somatoform, dissociative, anxiety, mood, eating, alcohol and substance abuse disorders |

| Part II: Psychotic and cognitive disorders, insight, functional impairment |

| II. Item Group Checklist |

| Signs and symptoms derived from case records, other providers, other collateral sources |

| III. Clinical History Schedule |

| Education, personality disorders, social impairment |

Adapted from Skodol AE, Bender DS: Diagnostic interviews in adults. In Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, editors: Handbook of psychiatric measures, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Two additional general diagnostic scales may be used to track changes in global function over time and in response to treatment. Both are clinician-rated and require only a few moments to complete. The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) consists of a 100-point single-item rating scale that is included in Axis V of the DSM-IV diagnosis (Table 6-6). Higher scores indicate better overall psychosocial function. Ratings can be made for current function and for highest function in the past year. The Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI) consists of two scores, one for severity of illness (CGI-S), and the other for degree of improvement following treatment (CGI-I). For the CGI-S, scores range from 1 (normal) to 7 (severe illness); for the CGI-I, they range from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse). A related score, the CGI Efficacy Index, reflects a composite index of both the therapeutic and adverse effects of treatment. Here, scores range from 0 (marked improvement and no side effects) to 4 (unchanged or worse and side effects outweigh therapeutic effects).

Table 6-6 Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) Scoring

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 91-100 | Superior function in a wide range of activities; no symptoms |

| 81-90 | Good function in all areas; absent or minimal symptoms |

| 71-80 | Symptoms are transient and cause no more than slight impairment in functioning |

| 61-70 | Mild symptoms or some difficulty in functioning, but generally functions well |

| 51-60 | Moderate symptoms or moderate difficulty in functioning |

| 41-50 | Serious symptoms or serious difficulty in functioning |

| 31-40 | Impaired reality testing or communication, or seriously impaired functioning |

| 21-30 | Behavior considerably influenced by psychotic symptoms or inability to function in almost all areas |

| 11-20 | Some danger of hurting self or others, or occasionally fails to maintain hygiene |

| 1-10 | Persistent danger of hurting self or others, serious suicidal act, or persistent inability to maintain hygiene |

| 0 | Inadequate information |

Adapted from Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV-TR fourth edition (text revision), Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

SCALES FOR MOOD DISORDERS

The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) is a clinician-administered instrument that is widely used in both clinical and research settings. Its questions focus on the severity of symptoms in the preceding week; as such, the HAM-D is a useful tool for tracking patient progress after the initiation of treatment. The scale exists in several versions, ranging from 6 to 31 items; longer versions include questions about atypical depression symptoms, psychotic symptoms, somatic symptoms, and symptoms associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Patient answers are scored by the rater from 0 to 2 or 0 to 4 and are tallied to obtain an overall score. Scoring for the 17-item HAM-D-17, frequently used in research studies, is summarized in Table 6-7. A decrease of 50% or more in the HAM-D score suggests a positive response to treatment. While the HAM-D is considered reliable and valid, important caveats include the necessity of training raters and the lack of inclusion of certain post-DSM-III criteria (such as anhedonia).

Table 6-7 Scoring the 17-Item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D-17)

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0-7 | Not depressed |

| 8-13 | Mildly depressed |

| 14-18 | Moderately depressed |

| 19-22 | Severely depressed |

| ≥23 | Very severely depressed |

Adapted from Kearns NP, Cruickshank CA, McGuigan KJ, et al: A comparison of depression rating scales, Br J Psychiatry 141:45-49, 1982.

The most frequently used self-administered depression rating scale is the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The BDI is a 21-item scale in which patients must rate their symptoms on a scale from 0 to 3; the total score is tallied and interpreted by the clinician (Table 6-8). Like the HAM-D, the BDI may be used as a repeated measure to follow progress during a treatment trial. Although easy to administer, the BDI tends to focus more on cognitive symptoms of depression, and it excludes atypical symptoms (such as weight gain and hypersomnia). An alternative rating scale, the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS), provides more thorough coverage of atypical depression and symptoms of dysthymia. The IDS is available in both clinician-rated (IDS-C) and self-administered (IDS-SR) versions, and it contains 28 or 30 items. Suggested interpretation guidelines are given in Table 6-9.

Table 6-8 Scoring the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0-9 | Minimal depression |

| 10-16 | Mild depression |

| 17-29 | Moderate depression |

| >29 | Severe depression |

Table 6-9 Scoring the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (IDS)

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0-13 | Normal |

| 14-22 | Mildly ill |

| 22-30 | Moderately ill |

| 30-38 | Moderately to severely ill |

| >38 | Severely ill |

Two other self-administered scales, the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (Zung SDS) and the Harvard Department of Psychiatry National Depression Screening Day Scale (HANDS), are frequently employed in primary care and other screening sessions due to their simplicity and ease of use. The Zung SDS contains 20 items, with 10 items keyed positively and 10 keyed negatively; subjects score each item as present from 1 or “a little of the time” to 4 or “most of the time.” To obtain the total score, positively keyed items are reversed and then all of the items are summed (Table 6-10). The HANDS includes 10 questions about depression symptoms, and it is scored based on the experience of symptoms from 0 or “none of the time” to 3 or “all of the time” (Table 6-11). Although the Zung SDS and HANDS take only a few minutes to administer, they are less sensitive to change than are the HAM-D and the BDI; like these other scales, the Zung SDS lacks coverage for atypical symptoms of depression.

Table 6-10 Scoring the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (Zung SDS)

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0-49 | Normal |

| 50-59 | Minimal to mild depression |

| 60-69 | Moderate to severe depression |

| >69 | Severe depression |

Table 6-11 Scoring the Harvard Department of Psychiatry National Depression Screening Day Scale (HANDS)

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0-8 | Unlikely depression |

| 9-16 | Likely depression |

| >16 | Very likely depression |

SCALES FOR PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS

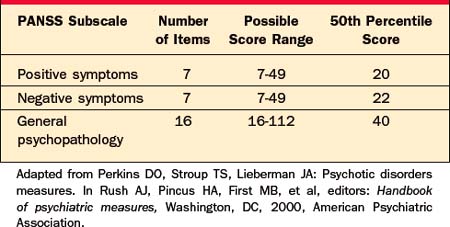

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is a 30-item instrument that emphasizes three clusters of symptoms: positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions, and disorganization), negative symptoms (e.g., apathy, blunted affect, and social withdrawal), and general psychopathology (which includes a variety of symptoms, e.g., somatic concerns, anxiety, impulse dyscontrol, psychomotor retardation, mannerisms, and posturing). Separate scores are tallied for each of these clusters, and a total PANSS score is calculated by adding the scores of the three subscales. Each item is rated on a scale from 1 (least severe) to 7 (most severe) following a semistructured interview (the Structured Clinical Interview for Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, SCI-PANSS). Normative data for the PANSS subscales, taken from a sample of 240 adult patients who met DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia, are given in Table 6-12.6 Designed to organize data from a broad range of psychopathology, the PANSS provides an ideal scale for monitoring baseline symptoms and response to antipsychotic medications. However, it can take 30 to 40 minutes to administer and score the PANSS, and examiners must have familiarity with each of the PANSS items.

Several additional instruments are available to assess global psychopathology and positive and negative symptom severity in psychotic patients. The 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) evaluates a range of positive and negative symptoms, as well as other categories (such as depressive mood, mannerisms and posturing, hostility, and tension). Each item is rated on a 7-point scale following a clinical interview. The BPRS has been used to assess psychotic symptoms in patients with both primary psychotic disorders and secondary psychoses, such as depression with psychotic symptoms. More detailed inventories of positive and negative symptoms are possible with the 30-item Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Table 6-13) and the 20-item Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Table 6-14). For each of these instruments, items are rated on a scale of 0 to 5 following a semistructured clinical interview, such as the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH). Correlations between SAPS and SANS scores with their counterpart subscales in the PANSS are quite high.6 Recently it has been argued that the SANS demonstrates higher validity if attention scores are removed.7

Table 6-13 Domains of the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)

| SAPS Domain | Number of Items | Possible Score Range |

|---|---|---|

| Hallucinations | 6 | 0–35 |

| Delusions | 12 | 0–70 |

| Bizarre behavior | 4 | 0–20 |

| Formal thought disorder | 8 | 0–40 |

Table 6-14 Domains of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

| SANS Domain | Number of Items | Possible Score Range |

|---|---|---|

| Affective flattening and blunting | 7 | 0-35 |

| Alogia | 4 | 0-20 |

| Avolition-apathy | 3 | 0-15 |

| Anhedonia-asociality | 4 | 0-20 |

| Attentional impairment | 2 | 0-10 |

An additional consideration in evaluating negative symptoms is whether they occur as a primary component of the disorder, or as a consequence of co-morbid processes, such as depression, drug effects, or positive symptoms. The Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome (SDS) uses four criteria to establish whether negative symptoms are present, enduring, and unrelated to secondary causes (Table 6-15). Each of the four criteria must be satisfied for a patient to qualify for the deficit syndrome, as defined by Carpenter and colleagues.8

Table 6-15 Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome (SDS)

| Criterion 1 |

Adapted from Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, Mckenney PD, et al: The Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome: an instrument for research in schizophrenia, Psychiatry Res 30:119-123, 1989.

SCALES FOR ANXIETY DISORDERS

The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) is the most commonly used instrument for the evaluation of anxiety symptoms. The clinician-implemented HAM-A contains 14 items, with specific symptoms rated on a scale from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (severe, grossly disabling symptoms). Covered areas include somatic complaints (cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and muscular), cognitive symptoms, fear, insomnia, anxious mood, and behavior during the interview. Administration typically requires 15 to 30 minutes. Clinically significant anxiety is associated with total scores of 14 or greater; of note, scores in primarily depressed patients have been found in the range of 14.9 to 27.6, and those in patients with primary schizophrenia have been found to be as high as 27.5.9

A frequently used self-rated anxiety scale is the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). In this 21-item questionnaire, patients rate somatic and affective symptoms of anxiety on a four-point Leikert scale (0 = “not at all”, 3 = “severely: I could barely stand it”). Guidelines for interpreting the total score are given in Table 6-16. The BAI is brief and easy to administer, but like the HAM-A, it does not identify specific anxiety diagnoses or distinguish primary anxiety from co-morbid psychiatric conditions.

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0-9 | Normal |

| 10-18 | Mild to moderate anxiety |

| 19-29 | Moderate to severe anxiety |

| >29 | Severe anxiety |

Other anxiety rating scales are geared toward specific clinical syndromes. For example, the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) is a clinician-administered semistructured interview designed to measure the severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. The interview is preceded by an optional checklist of 64 specific obsessive and compulsive symptoms. Following the interview, the examiner rates five domains in both obsessive and compulsive subscales (Table 6-17), with a score of 0 corresponding to no symptoms and 4 corresponding to extreme symptoms. Total scores average 25 in patients with OCD, compared with less than 8 in healthy individuals.9 The Brief Social Phobia Scale (BSPS) consists of clinician-administered ratings in 11 domains related to social phobia (Table 6-18). Severity of each symptom is rated from 0 (none) to 4 (extreme), generating three subscale scores: Fear (BSPS-F), Avoidance (BSPS-A), and Physiological (BSPS-P). These scores are summed in the Total Score (BSPS-T). A total score greater than 20 is considered clinically significant. Posttraumatic stress–associated symptoms can be measured with the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS), which is closely matched to DSM-IV criteria. The CAPS contains 17 items that are assessed by the clinician during a diagnostic interview; each item is rated for frequency, from 0 (never experienced) to 4 (experienced daily), and for intensity, from 0 (none) to 4 (extreme). The items follow each of the four DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as several extra items related to frequently encountered co-morbid symptoms (such as survivor guilt and depression). Scores are tallied within all DSM-IV diagnostic criteria to determine whether the patient qualifies for a PTSD diagnosis.

Table 6-17 Domains of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS)

| Domain | Obsession Score Range | Compulsion Score Range |

|---|---|---|

| Amount of time that symptoms occupy | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Interference with normal functioning | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Subjective distress caused by symptoms | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Degree that patient resists symptoms | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Degree that patient can control symptoms | 0-4 | 0-4 |

Adapted from Shear MK, Feske U, Brown C, et al: Anxiety disorders measures. In Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, editors: Handbook of psychiatric measures, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Table 6-18 Domains of the Brief Social Phobia Scale (BSPS)

| Domain: Avoidance and Fear Symptoms | Possible Avoidance Score Range | Possible Fear Score Range |

|---|---|---|

| Public speaking | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Talking to authority figures | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Talking to strangers | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Being embarrassed or humiliated | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Being criticized | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Social gatherings | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Doing something while watched | 0-4 | 0-4 |

| Total scores | 0-28 (BSPS-A) | 0-28 (BSPS-F) |

| Physiological Symptoms | Possible Physiologic Score Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Blushing | 0-4 | |

| Trembling | 0-4 | |

| Palpitations | 0-4 | |

| Sweating | 0-4 | |

| Total score | 0-16 (BSPS-P) |

Adapted from Shear MK, Feske U, Brown C, et al: Anxiety disorders measures. In Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, editors: Handbook of psychiatric measures, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

SCALES FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE DISORDERS

The CAGE questionnaire is ubiquitously used to screen for alcohol abuse and dependence. Consisting of four “yes/no” questions (organized by a mnemonic acronym) about alcohol consumption patterns and their psychosocial consequences, the CAGE takes only a few moments to administer(Table 6-19). Positive answers to at least two of the four questions signify a positive screen and the necessity of a more extended work-up; sensitivity of a positive screen has been measured at 0.78 to 0.81, and specificity at 0.76 to 0.96.10 Further, the psychometric measures for the CAGE are significantly better than are single questions (e.g., “How much do you drink?)” or laboratory values (such as Breathalyzer or liver function tests). A slightly longer, self-administered instrument called the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) contains 25 “yes/no” items concerning alcohol use. The MAST also includes questions about tolerance and withdrawal, and thus it can point out longer term problems associated with chronic alcohol abuse. While “no” answers are scored as 0, “yes” answers are weighted from 1 to 5 based on the severity of the queried symptom. Interpretation of the total MAST score is described in Table 6-20.

| C | Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking? |

| A | Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? |

| G | Have you ever felt bad or guilty about your drinking? |

| E | Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning (“eye-opener”) to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover? |

Table 6-20 Scoring the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST)

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0-4 | No alcoholism |

| 5-6 | Possible alcoholism |

| >6 | Probable alcoholism |

A readily administered screen for drug abuse or dependence, the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) is a self-rated survey of 28 “yes/no” questions. As with the MAST, the DAST includes questions about tolerance and withdrawal and can therefore identify chronic drug use problems. A briefer, 20-item version of the DAST is also available and has psychometric properties that are nearly identical to the longer version; however, each takes only a few minutes to administer and to score. A total score on the 28-item DAST of 5 or more is consistent with a probable drug abuse disorder.

Nicotine use is highly prevalent among patients with certain psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia). Smoking among psychiatric patients represents a concern not only because it places them at substantially higher risk for life-threatening medical problems, but also because it can interact with hepatic enzymes and significantly alter the metabolism of psychotropic drugs. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) is a six-item, self-rated scale that provides an overview of smoking habits and likelihood of nicotine dependence (Table 6-21). Although there is no recommended cutoff score for dependence, the average score in randomly selected smokers is 4 to 4.5.10

Table 6-21 The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence

Adapted from Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al: The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire, Br J Addiction 86:1119-1127, 1991.

SCALES FOR COGNITIVE DISORDERS

Diagnostic rating scales can be useful in identifying primary cognitive disorders (e.g., dementia) and for screening out medical or neurological causes of psychiatric symptoms (e.g., stroke-related depression). A positive screen on the cognitive tests described in this section often indicates the need for a more extensive work-up, which may include laboratory tests, brain imaging, or formal neurocognitive testing. As with formal cognitive batteries (which are described in detail in Chapter 8), it is important to keep in mind that the patient’s intelligence, level of education, native language, and literacy can greatly influence his or her performance on screen-ing cognitive tests, and these factors should be carefully considered when interpreting the results.

Useful as both a baseline screening tool and an instrument to track changes in cognition over time, the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) is one of the most widely used rating scales in psychiatry. The MMSE is a clinician-administered test that provides information on function across several domains: orientation to place and time, registration and recall, attention, concentration, language, and visual construction. It consists of 11 tasks, each of which is rated and summed to determine the total MMSE score (Table 6-22). A score of 24 or lower is widely considered to be indicative of possible dementia; however, early in the course of Alzheimer’s disease, patients can still perform comparably with unaffected individuals. A second limitation of the MMSE is that it does not include a test of executive function, and thus might fail to detect frontal lobe pathology in an individual with otherwise intact brain function.

| Point Value | Task |

|---|---|

| 5 | Orientation to state, country, town, building, floor |

| 5 | Orientation to year, season, month, day of week, date |

| 3 | Registration of three words |

| 3 | Recall of three words after 5 minutes |

| 5 | Serial 7s or spelling “world” backward |

| 2 | Naming two items |

| 1 | Understanding a sentence |

| 1 | Writing a sentence |

| 1 | Repeating a phrase (“No ifs, ands, or buts”) |

| 3 | Following a three-step command |

| 1 | Copying a design |

| 30 | Total possible score |

Adapted from Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician, J Psychiatr Res 12:189-198, 1975.

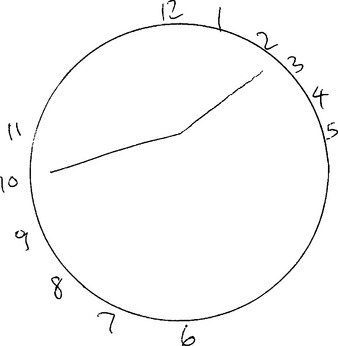

The Clock Drawing Test provides an excellent screen of executive function and can be a useful adjunct to the MMSE. In the test, patients are asked to draw the face of the clock, indicating a specified time. Figure 6-1 illustrates the clock drawn by a patient with a frontal lobe lesion; the patient was asked to indicate the time “10 to 2.” Note how the numbers are drawn outside the circle (which was provided by the examiner in this case) and are clustered joined than evenly spaced, indicating poor planning. The hands are joined near the top of the clock, near to the numbers 10 and 2, instead of at the center, indicating that the patient was stimulus bound to these numbers. The Clock Drawing Test can also detect neglect syndromes in patients with parietal lobe lesions; in these individuals, all of the numbers may be clustered together on one side of the circle.

The Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) presents a longer but often more prognostically valid instrument for dementia screening and follow-up. The DRS is a clinician-administered test that covers five cognitive domains (listed in Table 6-23), taking 30 to 40 minutes to complete. Within each domain, specific items are presented in hierarchical fashion, with the most difficult items presented first. If subjects are able to perform the difficult items correctly, many of the remaining items in the section are skipped and scored as correct. A cutoff score of 129 or 130 has been associated with 97% sensitivity and 99% specificity in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease in a large cohort of Alzheimer’s patients and healthy control subjects. Repeated measures of the DRS have been demonstrated to predict the rate of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease; further, performance deficits in specific domains have been significantly correlated with localized brain pathology. The DRS may also have some utility in differentiating Alzheimer’s disease from other causes of dementia, including Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and Huntington’s disease.11

Table 6-23 Domains of the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS)

| Domain | Contents | Point Value |

|---|---|---|

| Attention | Forward and backward digit span, one- and two-step commands, visual search, word list, matching designs | 0–37 |

| Initiation and perseveration | Verbal fluency, repetition, alternating movements, drawing alternating designs | 0–37 |

| Construction | Copying simple geometric figures | 0–6 |

| Conceptualization | Identifying conceptual and physical similarities among items, simple inductive reasoning, creating a sentence | 0–39 |

| Memory | Delayed recall of sentences, orientation, remote memory, immediate recognition of words and figures | 0–25 |

| Total score | 0–144 |

Adapted from Salmon DP: Neuropsychiatric measures for cognitive disorders. In Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, editors: Handbook of psychiatric measures, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

1 Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, Ross DE, et al. A separate disease within the syndrome of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:165-171.

2 Bear L, Jacobs DG, Meszler-Reizes J, et al. Development of a brief screening instrument: the HANDS. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69:35-41.

3 Mischoulon D, Fava M. Diagnostic rating scales and psychiatric instruments. In Stern TA, Herman JB, editors: Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatry update and board preparation, ed 2, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

4 Roffman JL, Stern TA. Diagnostic rating scales and laboratory tests. In Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem NH, et al, editors: Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry, ed 5, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2004.

5 Zarin DA. Considerations in choosing, using, and interpreting a measure for a particular clinical context. In: Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, editors. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

6 Perkins DO, Stroup TS, Lieberman JA. Psychotic disorders measures. In: Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, editors. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

7 Atbasoglu EC, Ozguven HD, Olmez S. Dissociation between inattentiveness during mental status testing and social inattentiveness in the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms attention subscale. Psychopathology. 2003;36:263-268.

8 Carpenter WT, Heinrichs DW, Wagman AMI. Deficit and nondeficit forms of schizophrenia: the concept. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:578-583.

9 Shear MK, Feske U, Brown C, et al. Anxiety disorders measures. In: Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, editors. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

10 Rounsaville B, Poling J. Substance use disorders measures. In: Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, editors. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

11 Salmon DP. Neuropsychiatric measures for cognitive disorders. In: Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, editors. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

Andreasen NC. Scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa, 1983.

Andreasen NC. Scale for the assessment of positive symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa, 1984.

Barnes TRE. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672-676.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561.

Beigel A, Murphy D, Bunney W. The manic state rating scale: scale construction, reliability, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;25:256.

Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LN, et al. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: the CAPS-1. Behav Therapist. 1990;18:187-188.

Davidson JRT, Potts NLS, Richichi EA, et al. The Brief Social Phobia Scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:48-51.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

Freedman M, Leach L, Kaplan E, et al. Clock Drawing: a neuropsychological analysis. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006-1011.

Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. Validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1012-1016.

Guy W: ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology—revised (DHEW pub no ADM 76-338), Rockville, MD, 1976, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health Psychopharmacology Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs.

Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62.

Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addiction. 1991;86:1119-1127.

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261-276.

Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, Mckenney PD, et al. The Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome: an instrument for research in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1989;30:119-123.

Mattis S. Mental status examination for organic mental syndrome in the elderly patient. In: Bellak L, Karasu TB, editors. Geriatric psychiatry: a handbook for psychiatrists and primary care physicians. New York: Grune & Stratton, 1976.

Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale: professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1988.

Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131:1121-1123.

Munetz MR, Benjamin S. How to examine patients using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39:1172-1177.

Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799.

Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, et al. The Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res. 1985;18:65-87.

Selzer ML. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;127:1653-1658.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22-33.

Simpson GM, Angus JWS. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;212:11-19.

Skinner HA. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addict Behav. 1982;7:363-371.

Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I. History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624-629.

Tuokko H, Hadjistavropoulos T, Miller JA, et al. The Clock Test: administration and scoring manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems, 1995.

Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). II. Multisite test-retest reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:630-636.

Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, et al. SCAN: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:589-593.

Wolf-Klein GP, Silverstone FA, Levy AP, et al. Screening for Alzheimer’s disease by clock drawing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:730-734.

Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, et al. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429-435.

Zung WWK. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70.

APPENDIX 6-1

| Scale | Author/Publisher | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SCID-I | New York State Psychiatric Institute | www.scid4.org |

| SCID-CV | American Psychiatric Press | www.appi.org |

| MINI | Sheehan et al (1998) | See ref.* |

| SCAN | American Psychiatric Press | www.appi.org |

| GAF | American Psychiatric Press | www.appi.org |

| CGI | Guy et al (1976) | See ref. |

| HAM-D | Hamilton (1960) | See ref. |

| BDI | The Psychological Corporation | www.psychcorp.com |

| IDS | Rush et al (1985) | See ref. |

| Zung SDS | Zung (1965) | See ref. |

| HANDS | Baer et al (2000) | See ref. |

| MSRS | Beigel et al (1971) | See ref. |

| Y-MRS | British Journal of Psychiatry | See ref. |

| PANSS | Multi-Health Systems, Inc. | www.mhs.com |

| BRPS | Overall et al (1988) | See ref. |

| SAPS | Andreasen et al (1984) | See ref. |

| SANS | Andreasen et al (1983) | See ref. |

| SDS | Kirkpatrick et al (1989) | See ref. |

| AIMS | Munetz et al (1986) | See ref. |

| BARS | Barnes et al (1989) | See ref. |

| EPS | Simpson et al (1970) | See ref. |

| HAM-A | Hamilton (1959) | See ref. |

| BAI | The Psychological Corporation | www.psychcorp.com |

| Y-BOCS | Goodman et al (1989) | See ref. |

| BSPS | Davidson et al (1991) | See ref. |

| CAPS | Blake et al (1990) | See ref. |

| CAGE | Mayfield et al (1974) | See ref. |

| MAST | Selzer (1971) | See ref. |

| DAST | Skinner (1982) | See ref. |

| FTND | Heatherton et al (1991) | See ref. |

| MMSE | Folstein et al (1975) | See ref. |

| Clock Drawing Test | Multi-Health Systems, Inc. | www.mhs.com |

| DRS | Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. | 800-331-8378 |

* See ref.: Refer to the reference list and suggested readings.

Collected from Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, editors: Handbook of psychiatric measures, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association. Note that copies of many of these rating scales are included in CD-ROM that accompanies the Handbook of Psychiatric Measures.