Case 6 Dermatitis/eczema

Description of dermatitis/eczema

Definition

Dermatitis, or eczema, is a superficial inflammatory disorder of the skin that can manifest as an acute, subacute or chronic disorder. Depending on the aetiology of the condition, dermatitis can be classified as either endogenous or exogenous. Endogenous forms include atopic, seborrhoeic, nummular and stasis dermatitis, while exogenous forms include contact and infective dermatitis.

Epidemiology

Atopic dermatitis affects between ten and twelve per cent of the population, occurring predominantly in children less than 5 years of age.1 Contact dermatitis affects between 1.5 and 14 per cent of the population and can develop at any age.2 Infective dermatitis can also occur at any age, while nummular and stasis dermatitis are most likely to occur in middle-aged people and elderly women, respectively.3

Aetiology and pathophysiology

There are many factors that contribute to the pathogenesis of dermatitis. The range of exogenous factors include, but are not limited to, chemicals, cosmetics, detergents, dyes, latex, metal compounds, mineral oils, plants, synthetic fibres, wool, topical drugs, and bacterial or fungal pathogens.3 Exposure to these agents can produce physiological effects ranging from skin damage and irritation (irritant contact dermatitis) to hypersensitivity reactions (allergic contact dermatitis), depending on individual susceptibility, concentration of the agent and duration of exposure.4

Myriad endogenous factors can also facilitate the development of dermatitis, including immunological abnormalities, such as a family history of atopic disease, environmental elements, such as food allergies, and psychoemotional influences, such as stress.4 Patients with endogenous dermatitis may also demonstrate diminished skin itch threshold, reduced ceramide content of the stratum corneum, decreased antimicrobial peptide production of keratinocytes, intestinal Candida overgrowth, increased proinflammatory cytokine production and intestinal dysbiosis.1 For contact dermatitis, an individual’s susceptibility to the condition may be increased through excessive water exposure, heat, sweating, low humidity and mechanical stress, such as repeated hand washing.2

Clinical manifestations

The three key manifestations of dermatitis, including erythema, heat and pruritus, are attributed to the underlying inflammatory process of the condition. These symptoms are common across all subtypes of dermatitis, although there are some distinct differences in the presentation of each subtype. Acute dermatitis, for instance, is associated with oedema, vesicle formation, pain, exudation and impaired function. Subacute dermatitis manifests as erosions, scaling, crusting and exfoliation, whereas chronic dermatitis appears as scaling, dryness, thickening and hardening of the skin.5 As well as the physical manifestations, dermatitis is also associated with a decline in health-related quality of life due to irritability, sleep disturbance and negative self-esteem and self-image.6

The clinical presentation of atopic eczema is somewhat more defined than the subtypes. According to Ring’s criteria, a diagnosis of atopic eczema may be made if four of the following criteria are present: pruritus, family history of atopy, IgE-mediated sensitisation, stigmata of atopic eczema, age-specific distribution of skin lesions and age-specific morphology.7

Clinical case

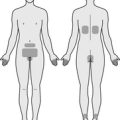

4-year-old boy with neck, cubital fossae and popliteal fossae dermatitis

Medical history

Lifestyle history

Illicit drug use

| Diet and fluid intake | |

| Breakfast | Nutri-Grain® cereal with full cream milk. |

| Morning tea | Apple, raisin bread. |

| Lunch | Spaghetti bolognaise, lasagne, vegetable slice, risotto with ham and peas, sandwich with white bread, margarine and jam or peanut butter. |

| Afternoon tea | Fruit, sweet biscuits. |

| Dinner | Beef schnitzel with mashed potato, ham and pineapple pizza, hot chips, roast chicken with roast potato and pumpkin, plain white pasta. |

| Fluid intake | 1 cup of juice daily, 1 cup of water daily, 1 cup of cordial daily, 1 cup of full cream milk daily. |

| Food frequency | |

| Fruit | 2–3 serves daily |

| Vegetables | 2–3 serves daily |

| Dairy | 2 serves daily |

| Cereals | 6–7 serves daily |

| Red meat | 2 serves a week |

| Chicken | 3 serves a week |

| Fish | 0–1 serve a week |

| Takeaway/fast food | 2–3 times a week |

Diagnostics

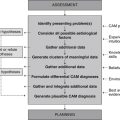

CAM practitioners may request, perform and/or interpret findings from a range of diagnostic tests in order to add valuable data to the pool of clinical information. While several investigations are pertinent to this case (as described below), the decision to use these tests should be considered alongside factors such as cost, convenience, comfort, turnaround time, access, practitioner competence and scope of practice, and history of previous investigations.

Diagnosis

Planning

Expected outcomes

Based on the degree of improvement reported in clinical studies that have used CAM interventions for the management of dermatitis,8–11 the following are anticipated.

Application

Diet

Elimination diet (Level I, Strength B, Direction +)

The effectiveness of the elimination diet in the treatment of dermatitis has been examined in a number of prospective studies and systematic reviews.8,12,13 The majority of these studies have shown that the elimination of eggs, and possibly cow’s milk, from infant diets effectively reduces the severity of dermatitis when the food allergy has been confirmed (i.e. the client has a positive specific IgE to eggs or cow’s milk). There is little evidence in support of elemental or general elimination diets, possibly because the presence of food allergy was not established in these studies.

Lifestyle

Relaxation therapy (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

The relaxation response can be induced by a number of behavioural therapies. In one RCT that involved 137 subjects with atopic dermatitis, autogenic relaxation training, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and a combined dermatological educational (DE) and CBT program resulted in significantly greater improvements in lesion severity and a significant reduction in topical steroid use when compared with DE or standard dermatological treatment alone.9

Nutritional supplementation

Ascorbic acid (Level III-2, Strength D, Direction o)

Even though serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (a marker of acute inflammation) have been shown to be inversely related to vitamin C levels in healthy elderly men,14 findings relating to the clinical effectiveness of ascorbic acid supplementation in atopic disease have been inconsistent. One study demonstrated an inverse relationship between vitamin C content of breastmilk and risk of atopic disease in infants,15 while two studies found a positive association between perinatal vitamin C intake and risk of atopic eczema in infants at 2 years of age.16,17

Lactobacillus spp. (Level I, Strength A, Direction + (for prevention only))

Probiotics exhibit local and systemic anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activity, although this may be more effective in the prevention of atopic eczema than as a treatment. This is highlighted in a recent meta-analysis of 10 RCTs, which concluded that probiotic supplementation, particularly with the L. rhamnosus strain, reduced the incidence of infant atopic dermatitis by thirty-nine per cent. As a treatment, probiotic supplementation was associated with only a small, statistically non-significant reduction in symptom severity.18

Omega 3 fatty acids (Level I, Strength A, Direction o)

The anti-inflammatory effects of essential fatty acids have been demonstrated in numerous population and clinical studies.19 In spite of this, a meta-analysis of 19 placebo-controlled trials found gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) and fish oil were no more effective than placebo at reducing the severity of atopic dermatitis.20

Selenium (Level II, Strength B, Direction o)

The mineral selenium exhibits a number of actions that may facilitate recovery in dermatitis. The inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB activation in vitro21 and the enhancement of T-cell function and B-cell activation and proliferation in healthy men22 are just a few of these effects. Yet in a double-blind RCT of 60 adults, selenium (600 μg daily for 12 weeks) had no statistically significant effect on the severity of atopic dermatitis when compared with placebo.23

Vitamin A (Level I, Strength B, Direction o)

While vitamin A is essential for collagen synthesis, epithelial cell differentiation, antibody production, phagocytosis and intercellular adhesion,24 these effects have not transpired in clinical research findings. In fact, a Cochrane review of vitamin A and eczema found only one placebo-controlled trial, and it concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of topical vitamin A preparations in the prevention or treatment of napkin dermatitis.24 The number of case reports that associate topical vitamin A preparations with contact dermatitis should also alert clinicians to the need for caution when using topically administered vitamin A.

Vitamin E (Level II, Strength C, Direction +)

The tocopherols show some promise as a treatment for dermatitis due to their capacity to decrease the release of proinflammatory cytokines and to reduce monocyte adhesion to endothelial tissue.25 This is partly supported by findings from a single-blind RCT of 96 subjects with atopic dermatitis. After 8 months of treatment, a greater number of patients receiving vitamin E supplementation (400 IU daily) demonstrated major improvement or complete remission of eczema and a larger reduction in serum IgE levels when compared with those receiving placebo.26

Zinc (Level III, Strength C, Direction o)

The use of zinc in the treatment of dermatitis is controversial. While this mineral has been shown to reduce spontaneous cytokine release and improve T-cell response in healthy elderly subjects,27 findings from a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 50 children (1–16 years) found oral zinc sulphate (185.4 mg per day for 8 weeks) to be no more effective than placebo at reducing the severity of atopic dermatitis.28

Iron, quercetin and vitamin D

These nutrients demonstrate an array of effects that could affect the outcomes of dermatitis;29–31 however, the efficacy of administration of these nutrients in dermatitis is not yet supported by rigorous clinical evidence, only by pathophysiologic rationale or experimental research findings. Given the diversity in organism physiology and metabolism, and the subsequent differences in dosage requirements between species, the translation of experimental data to human subjects is neither reliable nor appropriate.

Herbal medicine

Chamomilla recutita (Level II, Strength C, Direction +)

German chamomile exhibits a range of effects that are pertinent to the management of dermatitis, including anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, immunostimulant and mild sedative activity. The clinical efficacy of topically administered chamomile ointment, specifically, the proprietary product Kamillosan, has also been examined in a number of comparative trials and shown to be as effective as 0.25 per cent hydrocortisone, yet superior to 0.75 per cent fluocortin butyl ester and 5 per cent bufexamac in patients with eczema of the hands, forearms and lower legs after 3–4 weeks,32 more effective than 0.5 per cent hydrocortisone cream and placebo in patients with atopic dermatitis after 2 weeks33 and superior to 0.1 per cent hydrocortisone acetate and Kamillosan ointment base in subjects with experimentally induced toxic contact dermatitis.34 The methodological limitations of these trials suggest further research is needed.

Centella asiatica (Level IV, Strength D, Direction +)

Gotu kola is used in traditional Western herbal medicine for its anti-inflammatory and vulnerary activity. One of the constituents of the plant, madecassol, has been shown to be more effective than controls at reducing the severity of acute radiation dermatitis in rats. This could be attributed to the anti-inflammatory effect of the plant.35 The topical application of a C. asiatica extract and essential oil formulation in 20 adults also prevented wound infection in seventy-five per cent of contaminated wounds at 6 weeks, while healing sixty-four per cent of all acute and chronic wounds.36 The absence of blinding and a suitable control in this study and the lack of specific clinical data on the efficacy of gotu kola in dermatitis suggest further investigation is required.

Glycyrrhiza glabra (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

Licorice has a long history of use as an anti-inflammatory and demulcent agent. This use is partly supported by a double-blind RCT of 60 patients with atopic dermatitis that found the topical application of a two per cent licorice gel for 2 weeks to be more effective than one per cent licorice gel in reducing the scores for erythema, oedema and pruritus (p<0.05).37 Without a suitable control, it remains uncertain whether licorice offers any clinical benefit over and above the placebo effect.

Hypericum perforatum (Level II, Strength B, Direction +)

St John’s wort plays an important role in the treatment of integumentary disease due to its vulnerary, anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. Building on this traditional evidence are findings from a double-blind RCT of 21 patients with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. The study found that five per cent hypericum cream (standardised to 1.5 per cent hyperforin) applied twice daily for 4 weeks significantly reduced the intensity of eczematous lesions (p<0.05), as well as skin colonisation with Staphylococcus aureus (p = 0.06), when compared with placebo.11

Other

Aromatherapy (Level III-1, Strength D, Direction o)

Essential oils exhibit a range of physiological, emotional and psychological effects that may be useful in the overall treatment of dermatitis. To test this assumption, a small RCT set out to compare the efficacy of counselling and massage with essential oils to counselling and massage without essential oils in eight children with atopic dermatitis. After 8 weeks of daily therapy, improvements in dermatitis were evident, although the differences between groups were not statistically significant.38

Homeopathy (Level II, Strength C, Direction +)

Homeopathic medicine has long been used as a treatment of acute and chronic integumentary disorders. While good clinical evidence is lacking for many of these conditions, the evidence supporting the use of homeopathy in the management of dermatitis is promising, though not convincing. One small RCT of 29 patients showed the administration of a homeopathic complex for 10 weeks to be significantly more effective than placebo at improving seborrheic dermatitis.39 A prospective multicentre cohort study of 118 children has also found 12 months of homeopathic treatment to be as effective as conventional treatment at reducing dermatitis symptoms and disease-related quality of life.10

Massage (Level III-1, Strength D, Direction +)

Psychosocial stress can be an exacerbating factor in endogenous dermatitis. Thus, therapies that induce the relaxation response may be helpful in managing this form of dermatitis. One therapy that may be of particular benefit is massage. In a controlled clinical trial of 20 children suffering from atopic eczema, for instance, parent-administered massage, 20 minutes daily for 4 weeks, significantly (p<0.05) reduced erythema, lichenification, scaling, excoriation and pruritus, compared with the control, which demonstrated significant improvement only on the scaling measure.40

CAM prescription

Primary treatments

Referral

1. Hogan P.A. Atopic dermatitis. In Marks R., editor: Dermatology, 2nd ed, Sydney: Australasian Medical Publishing Company, 2005.

2. Nixon R.L., Frowen K.E. Contact dermatitis and occupational skin disease. In Marks R., editor: Dermatology, 2nd ed, Sydney: Australasian Medical Publishing Company, 2005.

3. Porter R., et al, editors. The Merck manual. Rahway: Merck Research Laboratories, 2008.

4. Graham-Brown R., Burns T. Lecture notes on dermatology, 9th ed. Oxford: Blackwell; 2007.

5. Buchanan P., Courtenay M. Prescribing in dermatology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

6. Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2006;60(8):984-992.

7. Ring J., Przybilla B., Ruzicka T. Handbook of atopic eczema, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2006.

8. Bath-Hextall F.J., Delamere F.M., Williams H.C. Dietary exclusions for established atopic eczema. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008. (1): CD005203

9. Ehlers A., Stangier U., Gieler U. Treatment of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of psychological and dermatological approaches to relapse prevention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(4):624-635.

10. Keil T., et al. Homoeopathic versus conventional treatment of children with eczema: a comparative cohort study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2008;16(1):15-21.

11. Schempp C.M., et al. Topical treatment of atopic dermatitis with St. John’s wort cream: a randomized, placebo controlled, double blind half-side comparison. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(Suppl 4):31-37.

12. Fiocchi A., et al. Dietary treatment of childhood atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome (AEDS). Allergy. 2004;59(S78):78-85.

13. Norrman G., et al. Significant improvement of eczema with skin care and food elimination in small children. Acta Paediatrica. 2007;94(10):1384-1388.

14. Wannamethee S.G., et al. Associations of vitamin C status, fruit and vegetable intakes, and markers of inflammation and hemostasis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;83(3):567-574.

15. Hoppu U., et al. Vitamin C in breast milk may reduce the risk of atopy in the infant. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;59(1):123-128.

16. Laitinen K., et al. Evaluation of diet and growth in children with and without atopic eczema: follow-up study from birth to 4 years. British Journal of Nutrition. 2005;94(4):565-574.

17. Martindale S., et al. Antioxidant intake in pregnancy in relation to wheeze and eczema in the first two years of life. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005;171(2):121-128.

18. Lee J., Seto D., Bielory L. Meta-analysis of clinical trials of probiotics for prevention and treatment of pediatric atopic dermatitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2008;121(1):116-121.

19. Jho D.H., et al. Role of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in inflammation and malignancy. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2004;3(2):98-111.

20. van Gool C.J., Zeegers M.P., Thijs C. Oral essential fatty acid supplementation in atopic dermatitis-a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. British Journal of Dermatology. 2004;150(4):728-740.

21. Vunta H., et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of selenium are mediated through 15-deoxy-Delta12, 14-prostaglandin J2 in macrophages. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(25):17964-17973.

22. Hawkes W.C., Kelley D.S., Taylor P.C. The effects of dietary selenium on the immune system in healthy men. Biological Trace Element Research. 2001;81(3):189-213.

23. Fairris G.M., et al. The effect on atopic dermatitis of supplementation with selenium and vitamin E. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1989;69(4):359-362.

24. Davies M.W., Dore A.J., Perissinotto K.L. Topical vitamin A, or its derivatives, for treating and preventing napkin dermatitis in infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005. (4): CD004300

25. Singh U., Devaraj S., Jialal I. Vitamin E, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2005;25:151-174.

26. Tsoureli-Nikita E., et al. Evaluation of dietary intake of vitamin E in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a study of the clinical course and evaluation of the immunoglobulin E serum levels. International Journal of Dermatology. 2002;41(3):146-150.

27. Kahmann L., et al. Zinc supplementation in the elderly reduces spontaneous inflammatory cytokine release and restores T cell functions. Rejuvenation Research. 2008;11(1):227-237.

28. Ewing C.I., et al. Failure of oral zinc supplementation in atopic eczema. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1991;45(10):507-510.

29. Giulietti A., et al. Monocytes from type 2 diabetic patients have a pro-inflammatory profile. 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D(3) works as anti-inflammatory. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2007;77(1):47-57.

30. Muthian G., Bright J.J. Quercetin, a flavonoid phytoestrogen, ameliorates experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by blocking IL-2 signaling through JAK-STAT pathway in T lymphocyte. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2004;24(5):542-552.

31. Shaheen S.O., et al. Umbilical cord trace elements and minerals and risk of early childhood wheezing and eczema. European Respiratory Journal. 2004;24(2):292-297.

32. Aertgeerts P., et al. Comparative testing of Kamillosan cream and steroidal (0.25% hydrocortisone, 0.75% fluocortin butyl ester) and non-steroidal (5% bufexamac) dermatologic agents in maintenance therapy of eczematous diseases. Zeitschrift fur Hautkrankheiten. 1985;60(3):270-277.

33. Patzelt-Wenczler R., Ponce-Poschl E. Proof of efficacy of Kamillosan(R) cream in atopic eczema. European Journal of Medical Research. 2000;5(4):171-175.

34. Nissen H.P., Biltz H., Kreysel H.W. Profilometry, a method for the assessment of the therapeutic effectiveness of Kamillosan ointment. Zeitschrift fur Hautkrankheiten. 1988;63(3):184-190.

35. Chen Y.J., et al. The effect of tetrandrine and extracts of centella asiatica on acute radiation dermatitis in rats. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1999;22(7):703-706.

36. Morisset R., et al. Evaluation of the healing activity of Hydrocotyle tincture in the treatment of wounds. Phytotherapy Research. 1987;1(3):117-121.

37. Saeedi M., Morteza-Semnani K., Ghoreishi M.R. The treatment of atopic dermatitis with licorice gel. Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 2003;14(3):153-157.

38. Anderson C., Lis-Balchin M., Kirk-Smith M. Evaluation of massage with essential oils on childhood atopic eczema. Phytotherapy Research. 2000;14(6):452-456.

39. Smith S.A., Baker A.E., Williams J.H. Effective treatment of seborrheic dermatitis using a low dose, oral homeopathic medication consisting of potassium bromide, sodium bromide, nickel sulfate, and sodium chloride in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Alternative Medicine Review. 2002;7(1):59-67.

40. Schachner L., et al. Atopic dermatitis symptoms decreased in children following massage therapy. Pediatric Dermatology. 1998;15(5):390-395.