CHAPTER 59

Pubalgia

Definition

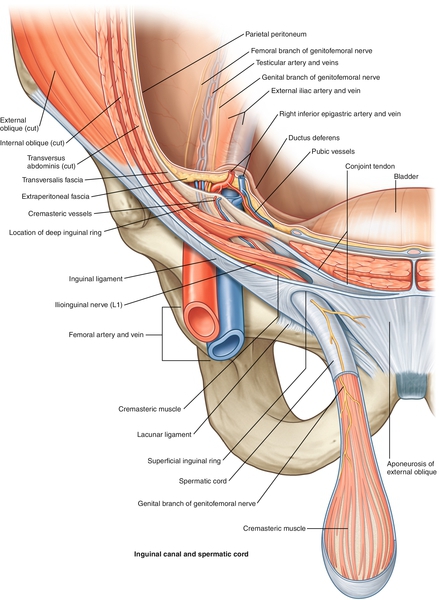

Although there is no universally accepted definition of this condition, pubalgia is pain in the groin area that is due to musculoskeletal causes. Despite the prevalence of the condition, the literature is filled with varying causes, anatomy involved, and terminology. Pubalgia usually refers to pain in the groin or lower abdominal area, typically in athletes who engage in activities involving repetitive sprinting, kicking, or twisting movements. Most of the published studies include athletes involved in soccer, rugby, ice hockey, running, or football. It is typically a multifactorial condition initially thought to be due to weakness of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal (Fig. 59.1). These patients have no obvious hernias or symptoms, such as numbness, clicking, a lump, or dysuria, to suggest other causes. However, medical causes need to be considered and recognized before it is concluded that the pain is due to a musculoskeletal cause [1,2]. The majority of the conditions resulting in chronic groin pain in athletes are musculoskeletal in origin [3,4]. There is ample evidence that this condition is much more common in amateur and professional athletes than in the general population [5–7].

Symptoms

The symptoms are often vague and diffuse and in the area of the lower abdomen, groin, or medial thigh. The pain is often insidious in onset and a chronic aching type [8]. Most athletes cannot remember how or when the pain started. The symptoms are worse during and after strenuous activity and exacerbated by an increase in abdominal pressure, such as coughing or sneezing. The pain may limit the ability to stand or to sit. In men, the pain can radiate into the testicle on the involved side and to the surrounding areas of the abdomen and lower back. Women may complain of a dull ache in the groin aggravated by physical exertion or intermittent neurologic pain in the distribution of the ilioinguinal nerve [9].

Physical Examination

The findings on examination can be tenderness in the area of the pubic symphysis [10,11] and pain on contraction of the hip flexors, hip adductors, or abdominal muscles [12]. Pain and tenderness at the external inguinal ring without a frank lump may be associated with pubalgia, but the presence of a lump would indicate an inguinal hernia [13]. Tenderness and dilation of the external inguinal ring can be found in up to 94% of patients with an athletic hernia [14]. Reduced range of motion of the short adductors of the hip may indicate injury to these muscles. Decreased internal hip range of motion can be due to osteitis pubis, whereas generalized reduction in hip range of motion is suggestive of hip joint disease. The muscles originating from the pubic area should be palpated to assess for possible strain (adductors, sartorius, rectus femoris, and rectus abdominis). A general examination of the region should be carried out to assess for other potential causes of the symptoms. This should include examination of the testis in men and the rectum in both sexes. A gynecologic examination may be indicated in a female patient. A multidisciplinary approach to the evaluation should be considered in these patients, given the spectrum of potential diagnoses and various areas involved (abdomen, genitourinary system, musculoskeletal system) [15,16].

Functional Limitations

Pubalgia can limit activities that require repetitive hip flexion or abduction on the side of the injury. Because the pain is usually brought on by activity, it can limit athletic activities such as kicking, sprinting, or twisting.

Diagnostic Studies

Plain radiography of the pelvis can be helpful in assessing for degenerative changes involving the hips, sacroiliac joints, and lower spine. In addition, it can be helpful in assessing for other bone disease, such as stress fractures or tumors. Osteitis pubis typically produces symmetric bone resorption and sclerosis and may show widening of the symphysis [17]. Magnetic resonance imaging can be helpful in assessing the soft tissues of the pelvis and proximal thigh. It can also detect bone marrow edema about the pubic symphysis and tendon injuries [18]. Magnetic resonance imaging can help with identifying hip joint disease, such as labral tears, which too can be manifested with activity-related groin pain of insidious onset in young to middle-aged patients [18]. Selective injections can have diagnostic value in differentiating the source of pain, for example, the symphysis pubis or hip joint [19]. These are usually performed with guidance by fluoroscopy or ultrasonography. Herniography can be a sensitive way to diagnose hernias [20]. Ultrasound examination is becoming an inexpensive and noninvasive way of assessing for hernias in the groin area and tendinopathy [21].

Treatment

Initial

The patient usually presents with chronic symptoms. However, when the patient does present with an acute groin injury or groin pain, the treatment should include rest, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesic medications, and ice. The patient may benefit from a muscle relaxant if there are muscle spasms.

Rehabilitation

There are limited studies in the literature on the treatment of pubalgia or adductor muscle strain and no specific protocols for therapy after surgery. Clinical experience dictates that the acute treatment consist of interventions to prevent further injury and inflammation. After the acute phase, the goals are to restore range of motion of the hip and to prevent muscle atrophy and deconditioning. The muscles that tend to be weak are the ipsilateral adductors, lower abdominals, ipsilateral gluteus medius and minimus, and contralateral tensor fascia lata. The patient may require stretching of surrounding muscles and need to learn techniques to transfer with less pain. The postoperative patient can have similar deficits and may benefit from the same therapies once wound healing is stable. Friction massage of the adductors may be needed. The stretching of the adductors should start in non–weight-bearing positions and then progress to weight bearing. Finally, functional training is a crucial component of the rehabilitation program [22].

Procedures

Patients with osteitis pubis can receive relief with fluoroscopically or sonographically guided corticosteroid injections [19]. Ultrasonography is gaining in popularity to aid in the diagnosis and treatment with corticosteroid injections around the nerves (ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral) and muscle origins (adductors, rectus femoris, sartorius, and rectus abdominis) in the inguinal region.

Surgery

Many patients continue to have symptoms despite conservative treatment; therefore surgery is often an option to eliminate the pain and return them to prior activities, including sports participation. However, most of the studies are case series without comparison to nonsurgical treatment. The surgical options fall into two categories: open versus laparoscopic. However, they are not compared in any of the studies. Only one prospective, randomized study is found that involved 66 soccer players with failed conservative treatment of groin pain. The patients were randomized into four groups: open surgical repair and neurotomy, individual training, physical therapy and NSAIDs, and controls [22]. Only the surgical group was found to have a statistically significant improvement in symptoms and ability to return to sport. Other surgeries include open repair of the posterior wall deficiencies [8,23]. More recently, laparoscopic procedures have become more popular. They tout quicker recovery and good responses [14,24–26].

Potential Disease Complications

In any condition that results in chronic pain, there is the risk of secondary complications of disuse atrophy, stiffening, and reduction in the range of motion of the affected joints and continued impact on the patient’s function and quality of life.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and NSAIDs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Aggressive stretching of the adductor muscles should be avoided in the acute phase as this may cause further pain and possible strain. Herniography is an invasive diagnostic study and there can be a risk for self-resolving bowel punctures.