CHAPTER 58 Congenital Heart Disease

5 What is a pulmonary hypertensive crisis? How is it treated?

In patients with PAH, the pulmonary vasculature is hyperreactive to various stimuli that cause pulmonary vasoconstriction. These stimuli include hypoxia, acidosis, hypercarbia, and stress associated with noxious stimuli such as pain or tracheal suctioning. When PVR suddenly increases as a result of such hyperreactivity to a point at which right ventricular pressure equals or exceeds left ventricular pressure, a pulmonary hypertensive crisis is said to occur. This is a dangerous situation in which death can occur as a result of rapidly progressive right ventricular failure, diminishing pulmonary blood flow and cardiac output, poor coronary artery flow, and hypoxia. Table 58-1 outlines the treatment of pulmonary hypertension.

| Goal | Method |

|---|---|

| Increase PO2 |

FiO2, Fractional concentration of oxygen in inspired gas; PO2, partial pressure of oxygen.

7 How are shunts calculated?

where Qp = pulmonary blood flow, Qs = systemic blood flow, SaO2 = systemic arterial oxygen saturation, SvO2 = systemic mixed venous oxygen saturation, SpvO2 = pulmonary venous oxygen saturation, and SpaO2 = pulmonary arterial oxygen saturation.

8 How are pulmonary vascular resistance and systemic vascular resistance calculated?

Resistance is related to pressure and flow:

where PAP = pulmonary artery pressure, LAP = left atrial pressure, Qp = pulmonary blood flow, MAP = mean arterial pressure, CVP = central venous pressure, and Qs = systemic blood flow. The results of this equation are expressed in Wood units. Multiply by 80 to express in dyne • s • cm−5.

12 What is tetralogy of Fallot? What are tet spells?

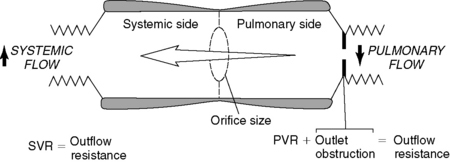

The tetrad of anatomic findings described by Fallot for this congenital heart lesion are pulmonary stenosis, overriding aorta, ventricular septal defect, and right ventricular hypertrophy. The pulmonary stenosis has a dynamic component: the subvalvular right ventricular outflow tract is muscular and contracts in response to inotropic stimuli (catecholamines). When such contraction occurs—or if SVR decreases significantly—less blood can flow into the pulmonary artery; thus more desaturated blood is shunted right to left across the ventricular septal defect into the left ventricle. An acute hypercyanotic episode, or tet spell, is the result (Figure 58-1).

13 How are tet spells treated?

Hypercyanotic spells and their treatment illustrate the importance of the balance between SVR and PVR (see Figure 58-1). In the presence of a shunt such as a ventricular septal defect, blood flow will follow the path of least resistance. If SVR is lower than PVR or right ventricular outflow tract resistance, as is the case in a tet spell, blood will shunt right to left. Treatment is aimed toward alteration of the resistance relationships (Table 58-2).

| Goal | Method |

|---|---|

| Relax the right ventricular outflow tract | β-blockade with propranolol 0.1 mg/kg or esmolol 0.5–1 mg/kg |

| Increase SVR |

FiO2, Fractional concentration of oxygen in inspired gas; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

14 What effects do anesthetic agents have on shunting in patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease?

17 Why can oxygen be dangerous in patients with single ventricle physiology?

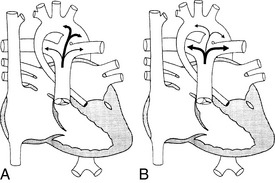

Maintenance of high PVR is of key importance in providing adequate systemic (and coronary) perfusion in infants with single ventricle physiology such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Ventilation with subambient oxygen concentrations (FiO2 0.16 to 0.18) or hypercarbic mixtures are frequently used for this purpose. If 100% oxygen is inadvertently administered, the acute decrease in PVR can rapidly lead to pulmonary edema from high Qp and to systemic hypotension and coronary ischemia from low Qs (Figure 58-2).

1. Friesen R.H., Williams G.D. Anesthetic management of children with pulmonary arterial hypertension [review]. Pediatr Anesth. 2008;18:208-216.

2. Hickey P.R., Wessel D.L. Anesthesia for treatment of congenital heart disease. In: Kaplan J.A., editor. Cardiac Anesthesia. 2nd ed. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1987:648.

3. Laussen P.C., Wessel D.L. Anesthesia for congenital heart disease. In: Gregory G.A., editor. Pediatric anesthesia. ed 4. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:467-539.

4. Wilson W., Taubert K.A., Gewitz M., et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116:1736-1754.