CHAPTER 57 Pediatric Anesthesia

1 What are the differences between the adult and pediatric airways?

TABLE 57-1 Differences Between the Adult and Pediatric Airways

| Infant Airway | Significance |

|---|---|

| Obligate nose breathers, narrow nares | Infants can breathe only through their noses, which can become easily obstructed by secretions. |

| Large tongue | May obstruct airway and make laryngoscopy and intubation difficult. |

| Large occiput | Sniffing position achieved with roll under shoulder. |

| Glottis located at C3 in premature babies, C3-C4 in newborns, and C5 in adults | Larynx appears more anterior; cricoid pressure frequently helps with laryngeal visualization. |

| Larynx and trachea are funnel shaped | Narrowest part of the trachea is at the vocal cords; the patient should have an ETT leak of <30 cm H2O to prevent excessive pressure on the tracheal mucosa, barotrauma. |

| Vocal cords slant anteriorly | Insertion of ETT may be more difficult. |

ETT, Endotracheal tube.

2 Are there any differences in the adult and pediatric pulmonary systems?

TABLE 57-2 Differences in the Pediatric and Adult Pulmonary Systems

| Pediatric Pulmonary System | Significance |

|---|---|

| Decreased, smaller alveoli | Thirteenfold growth in number of alveoli between birth and 6 years; threefold growth in size of alveoli between 6 years and adulthood |

| Decreased compliance | Increased likelihood of airway collapse |

| Increased airway resistance, vulnerability to smaller airways | Increased work of breathing and disease affecting small airways |

| Horizontal ribs, pliable ribs and cartilage | Inefficient chest wall mechanics |

| Less type 1, high-oxidative muscle | Babies tire more easily |

| Decreased total lung capacity, faster respiratory and metabolic rate | Quicker desaturation |

| Higher closing volumes | Increased dead-space ventilation |

3 How does the cardiovascular system differ in a child?

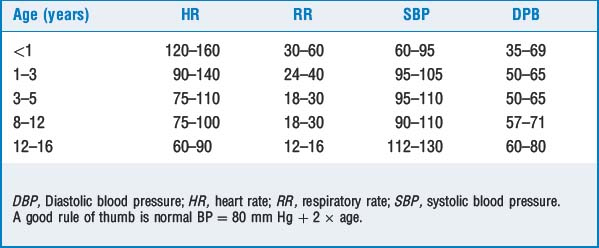

Newborns are unable to increase cardiac output (CO) by increasing contractility; they can increase CO only by increasing heart rate.

Newborns are unable to increase cardiac output (CO) by increasing contractility; they can increase CO only by increasing heart rate.8 Describe the commonly used induction techniques in children

Inhalational induction is the most common induction technique in children younger than 10 years who do not have intravenous (IV) access. The child is asked to breathe 70% nitrous oxide (N2O) and 30% oxygen for approximately 1 minute; sevoflurane is then turned on. The sevoflurane concentration can be increased slowly or rapidly.

Inhalational induction is the most common induction technique in children younger than 10 years who do not have intravenous (IV) access. The child is asked to breathe 70% nitrous oxide (N2O) and 30% oxygen for approximately 1 minute; sevoflurane is then turned on. The sevoflurane concentration can be increased slowly or rapidly. Rapid inhalational induction is used in an uncooperative child. The child is held down, and a mask containing 70% N2O, 30% oxygen, and 8% sevoflurane is placed on the child’s face. This unpleasant technique should be avoided if possible. Once anesthesia has been induced, the concentration of sevoflurane should be decreased.

Rapid inhalational induction is used in an uncooperative child. The child is held down, and a mask containing 70% N2O, 30% oxygen, and 8% sevoflurane is placed on the child’s face. This unpleasant technique should be avoided if possible. Once anesthesia has been induced, the concentration of sevoflurane should be decreased. Steal induction may be used if the child is already sleeping. Inhalational induction is accomplished by holding the mask near the child’s face while gradually increasing the concentration of sevoflurane. The goal is to induce anesthesia without awakening the child.

Steal induction may be used if the child is already sleeping. Inhalational induction is accomplished by holding the mask near the child’s face while gradually increasing the concentration of sevoflurane. The goal is to induce anesthesia without awakening the child. IV induction is used in a child who already has an IV line in place and in children >10 years. Typical medications used in children are thiopental, 5 to 7 mg/kg; propofol, 2 to 3 mg/kg; and ketamine, 2 to 5 mg/kg. EMLA cream (eutectic mixture of local anesthesia) applied at least 90 minutes before starting the IV infusion makes this an atraumatic procedure.

IV induction is used in a child who already has an IV line in place and in children >10 years. Typical medications used in children are thiopental, 5 to 7 mg/kg; propofol, 2 to 3 mg/kg; and ketamine, 2 to 5 mg/kg. EMLA cream (eutectic mixture of local anesthesia) applied at least 90 minutes before starting the IV infusion makes this an atraumatic procedure.9 How does the presence of a left-to-right shunt affect inhalational induction and intravenous induction?

11 What other special precautions need to be taken in a child with heart disease?

The anatomy of the lesion(s) and direction of blood flow should be determined. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) needs to be maintained. If the PVR increases, right-to-left shunting may increase and worsen oxygenation, whereas a patient with a left-to-right shunt may develop a reversal in the direction of blood flow (Eisenmenger’s syndrome). If a patient has a left-to-right shunt, decreasing the PVR may increase blood flow to the lungs and lead to pulmonary edema. Decreasing the PVR in patients with a right-to-left shunt may improve hemodynamics. Conditions that can increase shunting are listed in Table 57-5.

The anatomy of the lesion(s) and direction of blood flow should be determined. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) needs to be maintained. If the PVR increases, right-to-left shunting may increase and worsen oxygenation, whereas a patient with a left-to-right shunt may develop a reversal in the direction of blood flow (Eisenmenger’s syndrome). If a patient has a left-to-right shunt, decreasing the PVR may increase blood flow to the lungs and lead to pulmonary edema. Decreasing the PVR in patients with a right-to-left shunt may improve hemodynamics. Conditions that can increase shunting are listed in Table 57-5. Air bubbles should be meticulously avoided. If there is a communication between the right and left sides of the heart (ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect), air injected intravenously may travel across the communication and enter the arterial system. This may lead to central nervous system symptoms if the air obstructs the blood supply to the brain or spinal cord (paradoxical air embolus).

Air bubbles should be meticulously avoided. If there is a communication between the right and left sides of the heart (ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect), air injected intravenously may travel across the communication and enter the arterial system. This may lead to central nervous system symptoms if the air obstructs the blood supply to the brain or spinal cord (paradoxical air embolus). Prophylactic antibiotics should be given to prevent infective endocarditis. Recommendations for medications and doses can be found in the American Heart Association guidelines.

Prophylactic antibiotics should be given to prevent infective endocarditis. Recommendations for medications and doses can be found in the American Heart Association guidelines. Recognize and be able to treat a “tet spell.” Children with tetralogy of Fallot have right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) obstruction (pulmonary artery stenosis or atresia), an overriding aorta, ventricular septal defect, and right ventricular hypertrophy. They may or may not have cyanosis at rest. However, many are prone to hypercyanotic spells (tet spells) as they get older. Such episodes are characterized by worsening RVOT obstruction, possibly as a result of hypovolemia, increased contractility, or tachycardia during times of stimulation or stress. Patients are frequently treated with β-blockers, which should be continued perioperatively. Hypovolemia, acidosis, excessive crying or anxiety, and increased airway pressures should be avoided. The SVR should be maintained. If a hypercyanotic spell occurs in the perioperative period, treatment includes maintaining the airway, volume infusion, increasing the depth of anesthesia, or decreasing the surgical stimulation. Phenylephrine is extremely useful in increasing SVR. Additional doses of β-blockers may also be tried. Metabolic acidosis should be corrected.

Recognize and be able to treat a “tet spell.” Children with tetralogy of Fallot have right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) obstruction (pulmonary artery stenosis or atresia), an overriding aorta, ventricular septal defect, and right ventricular hypertrophy. They may or may not have cyanosis at rest. However, many are prone to hypercyanotic spells (tet spells) as they get older. Such episodes are characterized by worsening RVOT obstruction, possibly as a result of hypovolemia, increased contractility, or tachycardia during times of stimulation or stress. Patients are frequently treated with β-blockers, which should be continued perioperatively. Hypovolemia, acidosis, excessive crying or anxiety, and increased airway pressures should be avoided. The SVR should be maintained. If a hypercyanotic spell occurs in the perioperative period, treatment includes maintaining the airway, volume infusion, increasing the depth of anesthesia, or decreasing the surgical stimulation. Phenylephrine is extremely useful in increasing SVR. Additional doses of β-blockers may also be tried. Metabolic acidosis should be corrected.| Left-to-Right Shunt | Right-to-Left Shunt |

|---|---|

| Low hematocrit | Decreased SVR |

| Increased SVR | Increased PVR |

| Decreased PVR | Hypoxia |

| Hyperventilation | Hypercarbia |

| Hypothermia | Acidosis |

| Isoflurane | Nitrous oxide, ketamine |

PVR, Pulmonary vascular resistance; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

12 How is an endotracheal tube of appropriate size chosen?

An endotracheal tube (ETT) a half size above and a half size below the estimated size in Table 57-6 should be available, the leak around the tube should be <30 cm H2O, and the ETT should be placed to a depth of approximately three times its internal diameter.

| Age | Size—Internal Diameter (mm) |

|---|---|

| Newborns | 3.0–3.5 |

| Newborn–12 months | 3.5–4.0 |

| 12–18 months | 4.0 |

| 2 years | 4.5 |

| >2 years | ETT size = (16 + age)/4 |

ETT, Endotracheal tube.

13 Can cuffed endotracheal tubes be used in children and laryngeal mask airways?

14 How is an appropriate-size laryngeal mask airway chosen?

| Size of Child | LMA Size |

|---|---|

| Neonates up to 5 kg | 1 |

| Infants 5–10 kg | 1½ |

| Children 10–20 kg | 2 |

| Children 20–30 mg | 2½ |

| Children/small adults >30 kg | 3 |

| Children/adults >70 kg | 4 |

| Children/adults >80 kg | 5 |

LMA, Laryngeal mask airway.

15 How does the pharmacology of commonly used anesthetic drugs differ in children?

The minimal alveolar concentration (MAC) of the volatile agents is higher in children than adults. The highest MAC is in infants ages 1 to 6 months. Premature babies and neonates have a lower MAC, but it is still higher than in adults.

The minimal alveolar concentration (MAC) of the volatile agents is higher in children than adults. The highest MAC is in infants ages 1 to 6 months. Premature babies and neonates have a lower MAC, but it is still higher than in adults. Children have a higher tolerance to the dysrhythmic effects of epinephrine during general anesthesia with volatile agents.

Children have a higher tolerance to the dysrhythmic effects of epinephrine during general anesthesia with volatile agents.16 How is perioperative fluid managed in children?

18 What is the estimated blood volume in children?

TABLE 57-8 Guidelines for Estimated Blood Volume in Children

| Age | EBV (ml/kg) |

|---|---|

| Neonate | 90 |

| Infant up to 1 year old | 80 |

| Older than 1 year | 70 |

EBV, Estimated blood volume.

19 How is acceptable blood loss calculated?

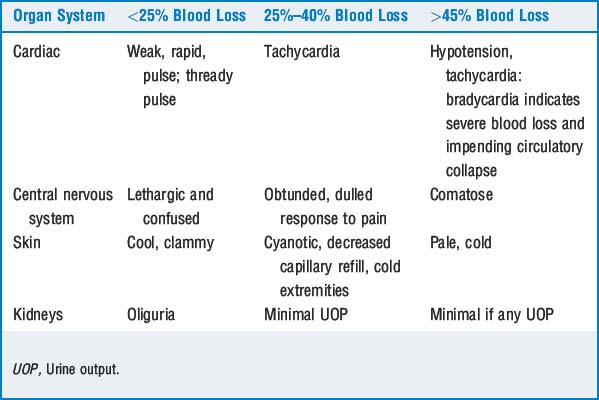

where ABL = acceptable blood loss, EBV = estimated blood volume, pt = patient, and hct = hematocrit. The lowest acceptable hematocrit varies with circumstances. Blood transfusion is usually considered when the hematocrit is <21% to 25%. If problems with vital signs develop, blood transfusion may need to be started earlier. For example, a 4-month-old infant is scheduled for craniofacial reconstruction. He is otherwise healthy, and his last oral intake was 6 hours before arriving in the operating room; weight = 6 kg, preoperative hct = 33%, lowest acceptable hct = 25%.

22 What is the most common type of regional anesthesia performed in children? Which local anesthetic is used and what dose is appropriate?

Bupivacaine (0.125% to 0.25%) is most commonly used. Bupivacaine 0.25% produces intraoperative analgesia and decreases the required volatile anesthetic. However, it may produce postoperative motor blockade that interferes with discharge of outpatients. Bupivacaine 0.125% causes minimal postoperative motor block but may not provide intraoperative analgesia or decrease the anesthetic requirements. Bupivacaine 0.175% produces good intraoperative analgesia and minimal motor block and decreases the required MAC of volatile anesthetics. The toxic dose of bupivacaine in the child is 2.5 mg/kg; in the neonate, 1.5 mg/kg. Commonly used doses are listed in Table 57-10.

TABLE 57-10 Commonly used Doses of Local Anesthetic for Caudal Block

| Dose (ml/kg) | Level of Block | Site of Operation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | Sacral/lumbar | Penile, lower extremity |

| 1 | Lumbar/thoracic | Lower abdominal |

| 1.2 | Upper thoracic | Upper abdominal |

UOP, Urine output.

Data from Gunter JB, et al: Optimum concentration of bupivacaine for combined caudal-general anesthesia in pediatric patients, Anesth Analg 66:995–998, 1982.

23 Describe the common postoperative complications

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is the most common cause of delayed discharge or unplanned admission. Factors associated with PONV include age >6 years, length of surgery >20 minutes, previous history of PONV, eye surgery, inner ear procedures, history of motion sickness, tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy, preoperative nausea or anxiety, hypoglycemia, female gender, gynecologic procedures, and use of opioids and N2O. The best treatment for PONV is prevention. Prophylactic administration of an antiemetic should be considered for patients at high risk for PONV. Avoiding opioids decreases the incidence of PONV as long as pain relief is adequate (e.g., patient has a caudal block). Management includes administering IV fluid, limiting oral intake, and administering dexamethasone, metoclopramide, or ondansetron.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is the most common cause of delayed discharge or unplanned admission. Factors associated with PONV include age >6 years, length of surgery >20 minutes, previous history of PONV, eye surgery, inner ear procedures, history of motion sickness, tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy, preoperative nausea or anxiety, hypoglycemia, female gender, gynecologic procedures, and use of opioids and N2O. The best treatment for PONV is prevention. Prophylactic administration of an antiemetic should be considered for patients at high risk for PONV. Avoiding opioids decreases the incidence of PONV as long as pain relief is adequate (e.g., patient has a caudal block). Management includes administering IV fluid, limiting oral intake, and administering dexamethasone, metoclopramide, or ondansetron. Laryngospasm and stridor are more common in children than in adults. Management for laryngospasm includes oxygen, positive pressure ventilation, jaw thrust, succinylcholine, propofol, and reintubation if necessary. Stridor is usually treated with humidified oxygen, steroids, and racemic epinephrine.

Laryngospasm and stridor are more common in children than in adults. Management for laryngospasm includes oxygen, positive pressure ventilation, jaw thrust, succinylcholine, propofol, and reintubation if necessary. Stridor is usually treated with humidified oxygen, steroids, and racemic epinephrine. Emergence agitation has increased in incidence with the use of short-acting volatile agents (sevoflurane and desflurane). Pain can worsen, and analgesics improve agitation. Agitation can occur even in patients undergoing nonpainful procedures, although fentanyl, 1 mg/kg, reduces agitation.

Emergence agitation has increased in incidence with the use of short-acting volatile agents (sevoflurane and desflurane). Pain can worsen, and analgesics improve agitation. Agitation can occur even in patients undergoing nonpainful procedures, although fentanyl, 1 mg/kg, reduces agitation.KEY POINTS: Pediatric Anesthesia

25 Should children with upper respiratory infection receive general anesthesia?

General recommendations for a child with a mild URI include the following:

The child who has a fever, rhonchi that do not clear with coughing, an abnormal chest x-ray film, elevated white count, or decreased activity levels should be rescheduled. The child presenting with symptoms of an uncomplicated URI and who are afebrile with clear secretions and appearing otherwise healthy or those with noninfectious conditions should be able to undergo surgery.

The child who has a fever, rhonchi that do not clear with coughing, an abnormal chest x-ray film, elevated white count, or decreased activity levels should be rescheduled. The child presenting with symptoms of an uncomplicated URI and who are afebrile with clear secretions and appearing otherwise healthy or those with noninfectious conditions should be able to undergo surgery.1. Francis A., Eltaki K., Bash T., et al. The safety of preoperative sedation in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:1517-1521.

2. Goldstein N.A., Pugazhendhi V., Rao S.M., et al. Clinical assessment of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatrics. 2004;114:33-43.

3. Gregory G.A. Pediatric anesthesia, ed 4. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

4. Tait A.R., Malviya S. Anesthesia for the child with an upper respiratory tract infection: still a dilemma? Anesth Analg. 2005;100:59-65.