CHAPTER 57

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Neuropathy

Earl J. Craig, MD; Daniel M. Clinchot, MD

Definition

Lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy, commonly called meralgia paresthetica, is the focal injury of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve causing pain and sensory loss in the lateral thigh of the affected individual. The incidence of lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy in the general population is 4.3 per 10,000 person-years. In addition, van Slobbe and colleagues [1] found that this neuropathy is more common in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome.

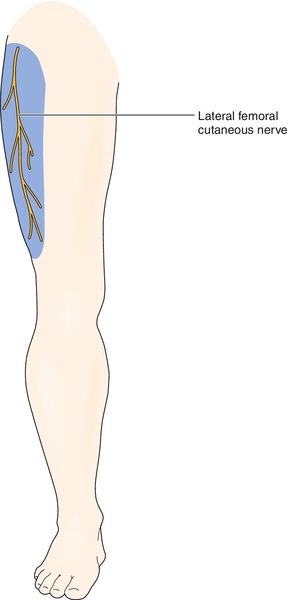

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is a pure sensory nerve that receives fibers from lumbar nerve roots L2-L3 (Fig. 57.1; see also Fig. 54.1). After forming, the nerve passes through the psoas major muscle and around the pelvic brim to the lateral edge of the inguinal ligament, where it passes out of the pelvis in a tunnel created by the inguinal ligament and the anterior superior iliac spine [2–4]. A number of anatomic variations have described the exit of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve from the pelvis [5]. Approximately 25% of the population has an anomalous course of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve out of the pelvis [6]. Approximately 12 cm below the anterior superior iliac spine, the nerve splits into anterior and posterior branches. The nerve provides cutaneous sensory innervation to the lateral thigh. The size of the area innervated varies among individuals.

The nerve may be injured as a result of a number of causes, as outlined in Table 57.1. Lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy is more commonly seen in overweight individuals because of compression of the nerve (due to abdominal girth) when the thigh is flexed in a seated position.

Symptoms

Patients typically complain of lateral thigh pain and numbness. The numbness may be described as tingling or a decrease in sensation. The pain is often burning in quality but may be sharp, dull, or aching. The patient may also complain of an itching sensation. In some instances, there will be a precipitating event, such as a long car ride in which the patient was seated for a prolonged period, putting stress on the nerve. This is especially true in individuals who wear the seat belt snuggly. The patient should not complain of weakness in the lower extremities. The diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion by the evaluating clinician.

Physical Examination

Because the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is purely sensory, the only finding typical of this condition is decreased sensation, which should be limited to an area of variable diameter in the lateral thigh. In adult men, the clinician may also see an area on the lateral thigh in which the hair has rubbed off. Palpation over the anterior superior iliac spine may exacerbate symptoms.

The physical examination is also used to exclude other possible causes of pain and weakness of the hip, thigh, and knee. A complete neuromuscular evaluation of the low back, the hips, and the entire lower extremities is needed. This examination should include inspection for asymmetry or atrophy, manual muscle testing, muscle stretch reflexes, and sensory testing for light touch and pinprick. In the case of lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy, the clinician should not see muscle atrophy or asymmetry or weakness of lower extremities. Reflexes should remain intact, and sensory testing outside of the lateral thigh should reveal intact function.

Functional Limitations

Typically, there are no functional limitations because this injury is more an annoyance than truly disabling. No true weakness is seen, although prolonged standing and extension at the hip may exacerbate the pain and thus limit the patient in performing tasks such as standing and walking. The nerve may be further compressed and the symptoms exacerbated when the patient is seated, so long car or plane rides may be difficult. Similarly, individuals who are sedentary at work may experience painful symptoms that limit their ability to function.

Diagnostic Studies

History and physical examination are the most important diagnostic tools, and all other testing should be used as an extension of these. Electromyography is the primary diagnostic tool and should include lateral femoral cutaneous sensory nerve conduction studies and needle electromyography of the lower extremity [3,4]. Although routine lateral femoral cutaneous nerve conduction studies have standard normal values with which an individual’s study result can be compared, it is generally recommended to do comparison studies on the unaffected side, as the studies are technically difficult [4,7–9]. The side-to-side amplitude ratio has been shown to be a better way to confirm the diagnosis [10]. Shin and colleagues [11] documented the utility of recording from two sites within the lateral femoral cutaneous dermatome. This technique facilitates use of a more realistic amplitude in the side-to-side comparison. Controversy exists in regard to the best site of stimulation of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Classically, the stimulation electrode is placed 1 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine. Recently, a stimulation site of 4 cm distal to the anterior superior iliac spine has been suggested as a means to obtain a more reliable response [12]. The needle electromyography is done to rule out other pathologic processes, and the recording should be normal. Serial electromyographic studies may help with evaluation of the recovery process.

Somatosensory evoked potentials may also be used, but a study reported that sensory conduction studies are a more reliable method of evaluation of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve [13]. High-resolution ultrasound has also been advocated for the assessment of lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy and has been found to highly correlate with electrodiagnostic findings [14]. Once the diagnosis is made, magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography of the pelvis may be required to look for a mass causing impingement.

Treatment

Initial

Treatment of lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy is focused on symptom relief and facilitation of nerve healing.

Both early and late symptomatic relief of the pain and numbness is attempted with modalities and medications. If an inflammatory component is suspected, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroids may be used. Narcotics are used when acetaminophen and anti-inflammatory medications do not control the pain. Acting as membrane stabilizers, antiseizure medications, such as carbamazepine and gabapentin, are also of benefit in some individuals [15,16].

Facilitation of healing varies according to the cause of the injury to the nerve. For most individuals, this entails removal of the cause of the pressure over the anterior iliac region. The pressure may be caused by tight clothing, belts, seat belts, or excess weight. Elimination of the pressure may include weight loss or clothing adjustment. Nerves that have sustained a less serious (neurapraxic) injury often heal within hours to weeks once the irritant is removed. Nerves that have sustained a more severe injury (neurotmesis or axonotmesis) typically have a much longer healing course because of the time required for wallerian degeneration and regeneration. The use of anti-inflammatory medications may also be of benefit in the healing process.

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy may facilitate healing of the injured nerve. Gentle stretching of the anterior thigh and groin is indicated to prevent contracture of the hip flexor muscles. The application of hot packs or ultrasound often facilitates the stretching process. Ice may be helpful when the patient continues to have swelling and inflammation around the pelvic brim. In some individuals, a general conditioning program to help with weight loss may also be useful. A dietitian can assist the patient with weight loss. A skilled therapist may be able to use soft tissue mobilization to help free an impinged and inflamed nerve. Augmented soft tissue mobilization is one of several techniques that may be useful. Electrical stimulation and transcutaneous nerve stimulation may be helpful in reducing the perception of pain by the patient during therapy treatments. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation can be used on a daily basis for pain control.

Procedures

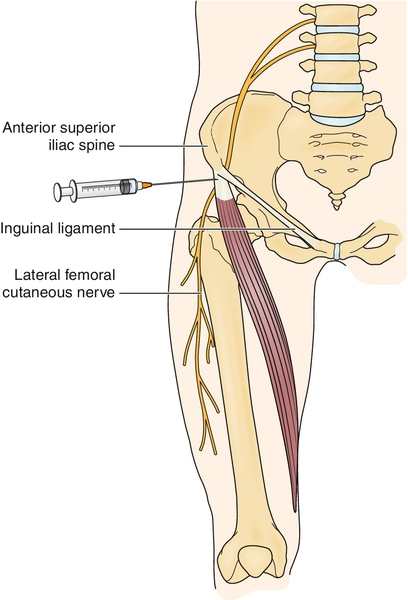

When conservative treatment fails, injection of the nerve at or near the anterior superior iliac spine with steroids and local anesthetic may be helpful (Fig. 57.2). If the steroid injection is helpful but short lasting, the nerve can be injected with phenol or other neurotoxic agents as a last resort.

Under sterile conditions, the pelvis is palpated and the anterior superior iliac spine and inguinal ligament are identified. A 25-gauge, 2-inch needle is placed perpendicular to the skin approximately 1 inch medial to the anterior superior iliac spine and inferior to the inguinal ligament. The needle is advanced into the soft tissue approximately 1 inch (this depends on the patient’s size and amount of excess subcutaneous tissue). At times, paresthesias may be elicited, thereby verifying needle placement; however, it is important not to inject directly into the nerve. Once the area to be injected is located, inject a 5- to 10-mL solution of local anesthetic and steroid (e.g., 2.5 mL of triamcinolone, 40 mg/mL, mixed with 2.5 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine). Ultrasound guidance of perineural lateral femoral cutaneous injection can significantly decrease failure rates by ensuring adequate needle localization [17].

Postinjection care may include icing of the injected area for 10 to 15 minutes and counseling of the patient to avoid pressure on the nerve.

Surgery

In the case of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve injury due to impingement, surgery may be required to remove the pressure. Surgical removal of neuroma or neurectomy proximal to the neuroma may also be helpful if a neuroma is found. In individuals with severe symptoms, neurolysis has been shown to result in a good outcome. This holds true even for individuals with prolonged symptoms. However, obesity has been associated with a poorer outcome when neurolysis is performed [18].

Potential Disease Complications

Potential complications include continued pain and numbness despite treatment.

Potential Treatment Complications

Complications of treatment are well recognized. Each medication has potential adverse side effects. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have the potential of gastric bleeding, decreased renal blood flow, and decreased platelet function. Narcotics have the potential for addiction and sedation. Carbamazepine can cause sedation and aplastic anemia. The patient taking carbamazepine should be evaluated with serial complete blood counts. Gabapentin can cause sedation. The injection of the nerve also has potential risks, which include bleeding, infection, and worsening of the pain. The potential risks of surgical intervention include bleeding, infection, and adverse reaction to the anesthetic agent.