CHAPTER 56

Hip Labral Tears

Matthew M. Diesselhorst, MD; Jonathan T. Finnoff, DO

Definition

A hip labral tear is a tear of the fibrocartilaginous labrum that attaches to the periphery of the acetabulum. The acetabular labrum is a horseshoe-shaped fibrocartilaginous structure that attaches to the peripheral rim of the acetabulum, contacts the articular surface of the femoral head, and blends inferiorly with the transverse acetabular ligament. The labrum plays a major biomechanical role in hip joint stabilization and function. It increases the effective depth of the acetabulum, increasing static stability; it contributes to hydrostatic pressurization of the intra-articular space, joint lubrication, and load distribution; and it has proprioceptive and nociceptive nerve function [1].

The labrum can be divided into two distinct zones: the well-vascularized extra-articular side consisting of dense connective tissue; and the intra-articular side, which is largely avascular [2]. The chondrolabral junction is not uniform and has lower biomechanical strength at its anterosuperior acetabular attachment, which contributes to the higher incidence of labral tears in this area [3,4].

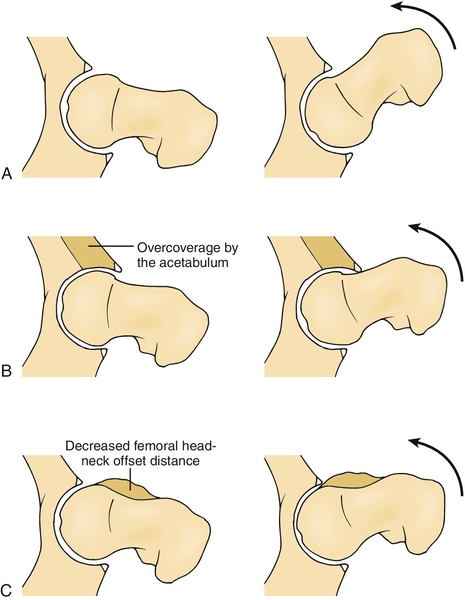

Hip injuries account for 3.1% to 8.4% of sports injuries, and labral tears are present in 22% to 55% of athletes with hip complaints [3,4]. Labral tears may be due to hip instability, iliopsoas impingement, trauma, and osteoarthritis. Many labral tears are associated with a condition called femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) [5,6]. FAI is characterized by abnormal contact between the femoral head-neck junction and the acetabular rim caused by abnormal bone morphology. Ganz and colleagues [7] described two types of FAI: pincer and cam. Pincer-type FAI is due to excessive femoral head coverage by the acetabulum (Fig. 56.1), whereas cam-type FAI results from a decrease in the femoral head-neck offset distance (Fig. 56.1). Pincer-type FAI typically occurs in middle-aged women; cam-type FAI is more common in men in their fourth decade. Most cases of FAI have components of both pincer and cam types.

Whereas labral tears associated with both types of FAI tend to occur in the anterosuperior region, the bone abnormalities in cam-type and pincer-type FAI cause different patterns of labral tears. In pincer-type impingement, repeated contact between the femoral neck and the prominent anterior aspect of the acetabular rim leads to labral degeneration, tears, intrasubstance ganglion formation, and, occasionally, labral ossification. In cam-type impingement, abnormal contact between the femoral head-neck junction and the acetabulum produces an outside-in abrasion of the acetabular cartilage and delamination between the acetabular cartilage and the adjacent labrum and subchondral bone [2]. The labral tears tend to occur on the articular rather than on the capsular surface. Although the bone patterns of FAI may differ, more commonly the osseous dysmorphism is a combined pattern.

Symptoms

Patients with labral tears complain of anterior groin pain made worse by long periods of standing, sitting, or walking. The pain can also be referred to the gluteal area or the trochanteric region. The onset of pain is usually insidious, with the patient often unable to recall a specific inciting event [2]. On occasion, the labral tear is due to trauma. Mechanical symptoms of clicking, locking, and instability are highly variable and not always indicative of intra-articular disease. A thorough history is critical, including inquiry about childhood diseases such as hip dysplasia, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, and slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

Physical Examination

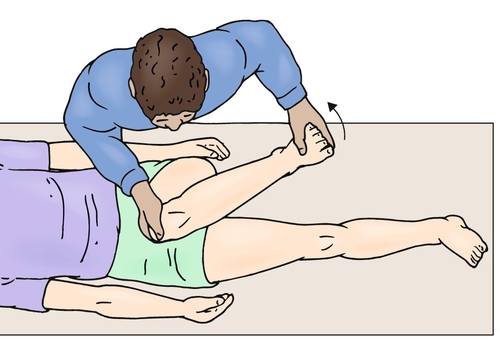

The hip examination should begin by observing the patient’s gait for antalgia. Palpation of the hip girdle may reveal some tenderness in the groin region, but this is a nonspecific finding. Lumbar spine, hip, and knee range of motion should be assessed. Frequently, pain will be provoked with hip internal rotation during the hip range of motion assessment. A neurologic examination of the lower extremities should be completed, including evaluation of strength, sensation, and reflexes. The neurologic examination findings are typically normal. The most reliable test for FAI and a labral tear is the anterior hip impingement test, which is done by flexing the hip beyond 90 degrees, then adducting and internally rotating the hip (Fig. 56.2). The result is considered positive if the test elicits anterior groin pain [8]. A hip scouring maneuver, in which the hip is taken from an abducted and externally rotated position, through a flexed and neutral rotation position, and finally into adduction and internal rotation, may produce pain and possibly a “click” if a labral tear is present. Passive hip extension and external rotation may cause pain if a labral tear is present. This is commonly referred to as the posterior impingement test. Hip disease can also be provoked by placing the patient’s leg in a figure four position. This test is referred to as the Patrick test or FABER test because the hip is in a flexed, abducted, and externally rotated position. Intra-articular hip disease can also be elicited by a resisted straight-leg raise in the supine position. Although a detailed physical examination assists the clinician in determining that the patient’s pain is coming from the hip joint, it is nonspecific and cannot differentiate between the various causes of hip pain.

Functional Limitations

Although it is uncommon, a patient with a labral tear may have a limp or a Trendelenburg gait and rarely may require an assistive device to walk. A labral tear may also cause pain that limits activities, such as gymnastics or construction work, that involve repetitive hip loading, pivoting, and deep flexion.

Diagnostic Studies

Plain radiographs remain the mainstay in evaluating hip pain. A minimum of two radiographic views must be obtained. Proper patient positioning is critical to correctly assess the osseous anatomy. Commonly, an anteroposterior pelvis view and a cross-table (false profile) lateral view of the affected hip are used. Wenger and colleagues [9] reviewed hip radiographs of patients with labral tears and found that 87% had at least one bone abnormality consistent with FAI.

Pincer-type FAI may be due to generalized overcoverage of the femoral head from an excessively deep acetabulum or focal overcoverage related to acetabular retroversion. On the anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis, the normal acetabulum should cover at least 75% of the femoral head. A deep acetabulum is present if the acetabular fossa or the femoral head projects medial to the ilioischial line. Focal acetabular retroversion is suggested by the cross-over sign, in which the cephalad portion of the anterior acetabular wall is lateral to the posterior acetabular wall. The cross-table lateral radiograph may demonstrate posteroinferior joint space narrowing.

Cam-type FAI can be evaluated with anteroposterior pelvis and cross-table lateral radiographs [10]. The primary radiologic finding of cam-type FAI is a decrease in the anterior or superior femoral head-neck offset distance, which causes the femoral head-neck junction to appear flattened or convex rather than concave. The asphericity of the femoral head-neck junction caused by cam-type FAI is commonly referred to as a pistol grip deformity (Fig. 56.3).

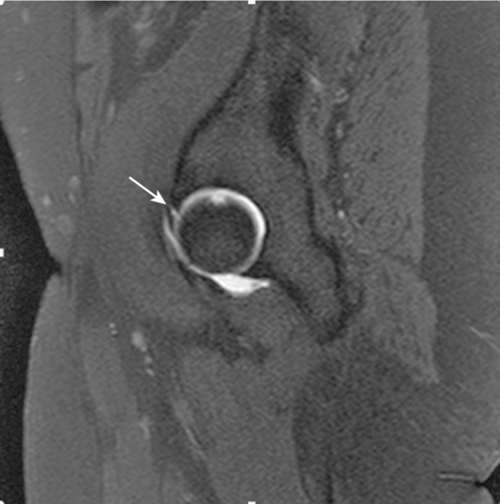

Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred imaging modality for intra-articular hip disease as it provides high-resolution images of the acetabular labrum, hip joint cartilage, and joint space [2]. Magnetic resonance arthrography is the combination of magnetic resonance imaging with intra-articular injection of a gadolinium-based contrast agent and is the test of choice for evaluation of the acetabular labrum (Fig. 56.4) [11].

Treatment

Initial

The initial treatment of labral tears should be conservative and may include local application of physical modalities, mild oral analgesics such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and rehabilitation. If the patient’s symptoms persist despite these measures, an intra-articular corticosteroid injection could be considered [12]. Patients should be instructed to avoid aggravating activities.

Rehabilitation

The rehabilitation program for acetabular labral tears should progress through three phases. The first phase should focus on pain reduction through physical modalities, activity modification, and mild analgesics. The patient should work on reestablishing full pain-free range of motion and perform static strengthening exercises of the hip girdle musculature. Core strengthening exercises should be introduced, and the patient should maintain aerobic fitness through pain-free forms of nonimpact aerobic conditioning exercises. Kinetic chain deficits should be identified and addressed. Proprioceptive exercises such as single-leg stance on a stable surface or double-leg stance on an unstable surface should be included in the program. The second phase of rehabilitation should gradually introduce nonpainful, dynamic hip girdle strengthening exercises and low- to moderate-impact aerobic conditioning. Core stability and proprioceptive exercises should be advanced according to the patient’s tolerance during this phase of rehabilitation. The final rehabilitation phase should transition the patient to sports-specific exercises (or work-specific exercises if the patient is not an athlete) and a home exercise program to maintain hip girdle strength and flexibility, core stability, aerobic fitness, and neuromuscular coordination [12].

An appropriate postsurgical rehabilitation program is necessary to maximize the patient’s recovery [13]. Immediately after surgery, measures should be taken to reduce the patient’s discomfort, including oral medications and local physical modalities. Compression should be applied at regular intervals to reduce postoperative edema. Frequently, a postoperative brace is used for the first 1 to 2 weeks during waking hours to prevent hip flexion beyond 80 degrees. At night, the patient may be required to wear an immobilizing brace to prevent hip external rotation, which places excessive tension on the anterior capsular structures. Gentle passive hip range of motion and active knee and ankle range of motion should be initiated. For the first 2 weeks after surgery, the patient should avoid excessive hip flexion, internal rotation, and abduction. As the pain resolves, the patient can begin working on reestablishing full pain-free range of motion. This usually takes place approximately 2 to 4 weeks after surgery. At 4 weeks after surgery, stretching exercises of the hip girdle and thigh musculature can be initiated.

Isometric hip girdle and thigh muscle strengthening can begin immediately after surgery but should be performed in a pain-free manner. Progression to isotonic hip girdle strengthening can begin after 2 to 4 weeks, with a focus on the hip abductors. Weight-bearing strengthening exercises typically can begin approximately 4 to 6 weeks after surgery. Exercises should include transverse plane movements but should always be pain free.

Partial weight bearing is continued for the first 2 to 6 weeks postoperatively, depending on the type of surgery performed and the surgeon’s preference. The patient is weaned off of crutches after that time is complete.

Functional rehabilitation exercises usually begin approximately 6 to 8 weeks after surgery. Aerobic conditioning can progress from a limited weight-bearing environment (e.g., pool), to nonimpact full weight bearing (e.g., elliptical machine), to walking and jogging. Most individuals are unable to progress to impact-type aerobic conditioning (e.g., running) and cutting or pivoting activities until 12 to 24 weeks after surgery. In general, manual laborers can return to unrestricted work approximately 12 to 24 weeks after surgery, whereas athletes can return to competitive sports after 12 to 32 weeks, depending on the type of surgery performed and their ability to progress through the rehabilitation program.

Procedures

Some patients with acetabular labral tears may benefit symptomatically from an intra-articular corticosteroid injection. Hip injections should be performed with image guidance, such as ultrasound or fluoroscopy, to ensure accurate placement of the injectate into the hip joint, to minimize potential complications, and to maximize the therapeutic efficacy of the injection. Hip injections are typically considered as a treatment option after the patient has failed to respond to other nonoperative measures, such as local physical modalities, medications, and rehabilitation. However, if the patient is in significant pain and cannot participate in a rehabilitation program because of the severity of the pain, an intra-articular corticosteroid injection could be considered early in treatment to reduce pain and to facilitate the rehabilitation program.

Surgery

Surgical treatment should be considered in patients who have failed to respond to nonoperative measures or have significant mechanical symptoms. Originally, hip labral tears were treated surgically with open labral débridement. More recently, the advent of hip arthroscopy has allowed access to the labrum with significantly less morbidity. Short-term good to excellent results have been achieved with arthroscopic labral débridement. However, most of these studies included subjects with additional hip disease (e.g., articular cartilage injury) and were performed before the recognition of FAI [14]. Recently, it has been suggested that the optimal surgical treatment of hip labral tears is to repair rather than to débride the labrum to restore normal labral function [8]. The most commonly used labral repair technique involves placement of simple stitches. Comparison studies between labral débridement and labral repair surgeries are lacking. Thus, future investigations are required to answer the question of which surgical technique results in the best clinical outcomes [14].

When surgically treating a labral tear, many surgeons advocate addressing bone dysmorphisms that cause FAI (e.g., acetabuloplasty for pincer-type FAI or femoroplasty for cam-type FAI). Although there is a recent trend toward addressing the bone abnormality, there is no definitive evidence that the clinical outcome achieved with combined treatment of the osseous abnormality and the labral tear will be more favorable than that provided by isolated treatment of the labral tear [2].

Potential Disease Complications

If left untreated, labral tears can cause pain, mechanical symptoms (e.g., snapping, popping, locking), functional limitations, and potentially osteoarthritis. If the patient also has FAI, the morphologic abnormalities of the femoral head or acetabulum result in abnormal contact between the femoral neck or head and the acetabulum. This leads to damage of the labrum and underlying cartilage. Theoretically, continued abnormal contact results in further deterioration and wear of the cartilage, with eventual onset of arthritis [15].

Potential Treatment Complications

Most nonoperative treatments have limited risk. The patient could have an allergic reaction to a medication, experience medication side effects such as dyspepsia, or have a medication complication such as gastric ulceration. Potential complications of intra-articular injections include infection, allergic reaction, and injury to adjacent neurovascular structures.

Potential complications of hip arthroscopy are mostly related to patient position and surgical technique. Traction is required for hip arthroscopy, which can cause nerve injury. This type of injury is minimized by avoidance of excessive traction and use of a wide post in the perineum. Adequate portal placement is of paramount importance in hip arthroscopy; inappropriate portal placement can lead to neurovascular injury and inadequate joint visibility, which can lead to iatrogenic structural damage [8].