CASE 55 Foreign Body Retrieval

Cardiac catheterization

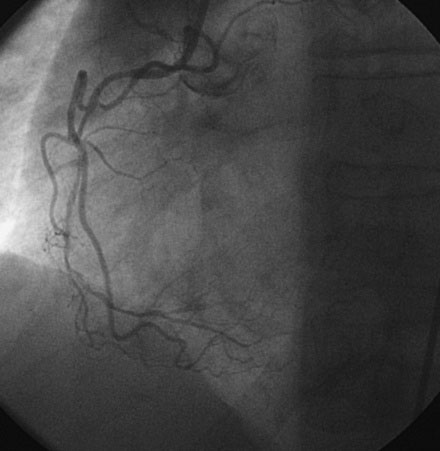

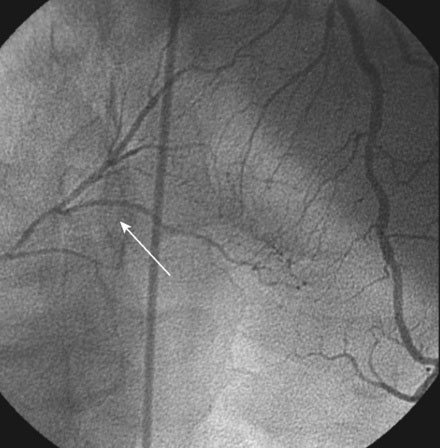

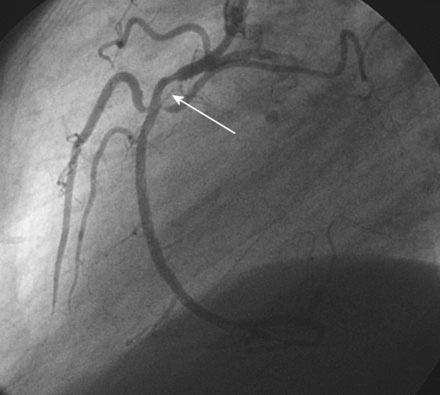

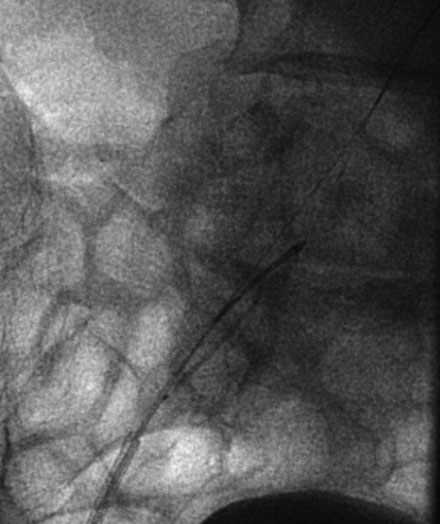

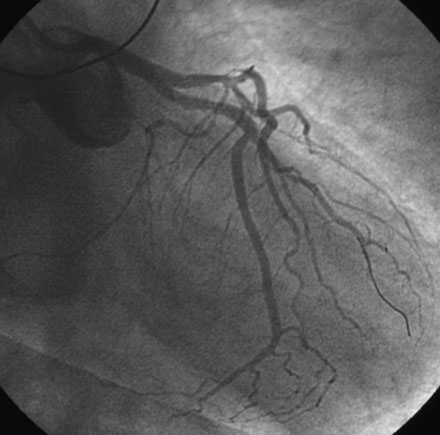

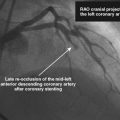

Left ventricular function was normal. Coronary angiography demonstrated complex and multivessel coronary disease. The right coronary artery was essentially totally occluded in the midportion with some anterograde flow (Figures 55-1, 55-2 and Videos 55-1, 55-2). Although the distal right coronary artery appeared small, the distal right coronary was believed to be larger, based on review of the prior angiogram and from the collateral visible from the left coronary artery (Figure 55-3). A long, moderate lesion was noted in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) (Figure 55-4) and the circumflex system appeared to be without significant stenosis (Figure 55-5). To determine the significance of the lesion, the operator further evaluated the LAD by assessing fractional flow reserve. Using a pressure wire and an intracoronary injection of adenosine to achieve maximum hyperemia, fractional flow reserve of the LAD was 0.69 and thus represented a significant lesion.

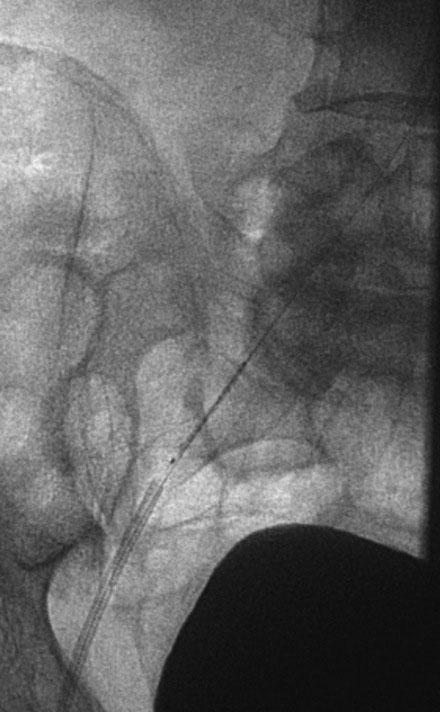

He received 300 mg of clopidogrel the night before the procedure. The operator used bivalirudin as the procedural anticoagulant and began with the occluded right coronary artery. A floppy-tipped guidewire easily crossed the occluded segment and a 2.0 mm diameter compliant balloon was used to restore patency of the artery. The operator positioned and deployed two 2.5 mm diameter by 28 mm long sirolimus-eluting stents across the lesion. A residual stenosis remained in the proximal segment (Figure 55-6 and Video 55-3) and the operator attempted to position a third sirolimus-eluting stent at this location. Despite the relative ease of passing the first two stents, the operator could not advance the stent across the lesion and thus decided to remove the stent and dilate the proximal end of the deployed stent as well as the unstented segment with a noncompliant balloon. During the attempt to remove the stent catheter from the coronary artery, the operator encountered significant resistance when the back end of the stent balloon entered the guide catheter. Despite gentle manipulations, the stent would not enter the guide catheter. Fearing that struts from the back end of the stent edge were raised from the surface of the balloon, and concerned about the possibility of stent embolization, the operator decided to remove the stent catheter and guide together as one unit into the descending aorta. The operator successfully removed the stent from the coronary artery and the stent remained in position on the balloon catheter with the 0.014 inch guidewire in place. The entire apparatus (guide, stent catheter, and guidewire) was withdrawn to the femoral artery sheath. Again, the operator noted resistance when he attempted to withdraw the stent into the femoral artery sheath (Figure 55-7) and decided to snare the end of the stent to prevent stent embolization during removal of the stent catheter. The guide catheter was removed from the femoral sheath by cutting the back end of the balloon catheter. A stiff 0.014 inch floppy-tipped guidewire (Mailman, Boston Scientific) was passed through the sheath to allow continued femoral access during sheath removal. The operator then passed a 4 French, 10 mm Amplatz GooseNeck snare through the femoral sheath alongside the stent catheter. The 0.014 inch guidewire was carefully withdrawn with about 10 cm of wire tip extending beyond the stent catheter. The open loop of the snare was manipulated to capture the 0.014 inch guidewire (Figure 55-8) and then carefully withdrawn to capture the wire near the end of the stent catheter (Figure 55-9 and Video 55-4). The operator removed the sheath, stent catheter, and snare together while maintaining femoral access with the other 0.014 inch stiff guidewire. The stent was successfully removed and a new sheath positioned in the femoral artery over the 0.014 inch wire. The operator decided to accept the angiographic result obtained and did not place any additional stents in the right coronary artery.

Discussion

Stent embolization occurs in about 0.3% of coronary interventions1,2 and is more common when stents are manually crimped onto the balloon catheter.1 Risk factors for stent embolization include severe proximal angulation and heavy coronary calcification. Stent embolization in the coronary artery typically occurs when a stent cannot be advanced and the operator tries to withdraw the stent catheter back into the guide. The stent may become caught in the lesion and shear off the balloon or, as demonstrated by this case, struts at the back end of the stent may become raised when the stent catheter is pulled back and is not entirely coaxial to the guide. In either case, if the operator does not detect the resistance or carelessly withdraws the stent catheter despite the resistance, then the stent may come off the balloon. In the case shown here, the operator sensed the resistance at the guide and decided to withdraw the entire apparatus, thereby at least preventing stent embolization into the coronary circulation.

When a stent embolizes into the coronary circulation, potentially serious consequences may arise if the stent cannot be successfully retrieved, including myocardial infarction, emergency surgery, and death.2–4 An undeployed stent sitting in a coronary artery can be managed in one of several ways. If the stent remains on the 0.014 inch guidewire, a low-profile 1.5 mm compliant balloon can be advanced within or just distal to the stent, inflated, and pulled into the guide catheter. Another method involves placing a second 0.014 inch guidewire alongside the original guidewire and the undeployed stent and twirling the two wires around each other in an attempt to ensnare the stent. In the author’s experience, this technique is often not possible because the undeployed stent is wedged within a lesion and a guidewire cannot be advanced around it. If the stent is not on a 0.014 inch guide wire, the operator may try to snare the stent within the coronary artery or capture it with a set of biopsy forceps; however, the latter method may result in significant arterial injury. Another popular method is to simply crush the undeployed stent against the wall of the coronary artery with a balloon and then another stent. However, this implies the operator will be successful at delivering a new stent to a location within an artery to which the operator could not initially successfully deliver a stent. By whatever method works, the operator should make an effort to retrieve or deploy the embolized stent to minimize the risk of an adverse event.

Embolization of a stent into the peripheral circulation appears to be a benign event.3,4 Usually, the stent embolizes into the lower extremity circulation. Often, it cannot be found. The outcome of these peripheral embolization events appears benign, although there are reports of claudication occurring due to stent embolization.

Prevention of embolization is desirable and operators should be sure the coronary is well-prepared before attempting to deliver a stent in a calcified, angulated lesion. Nevertheless, all interventionalists should be familiar with methods of retrieving embolized stents and foreign bodies. As shown in this case, the goose neck snares are easy to use and highly effective at capturing embolized devices. Care should be taken to carefully manage the vascular access site, since removal of the embolized and frequently distorted stent may enlarge the arteriotomy and result in increased access site bleeding.2

1 Eggebrecht H., Haude M., von Birgelen C., Oldenburg O., Baumgart D., Herrmann J., Welge D., Bartel T., Dagres N., Erbel R. Nonsurgical retrieval of embolized coronary stents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;51:432-440.

2 Brilakis E.S., Best P.J.M., Elesber A.A., Barsness G.W., Lennon R.J., Holmes D.R., Rihal C.S., Garratt K.N. Incidence, retrieval methods, and outcomes of stent loss during percutaneous coronary intervention: a large single center experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;65:333-340.

3 Kozman H., Wiseman A.H., Cook J.R. Long term outcome following coronary stent embolization or misdeployment. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:630-634.

4 Kammler J., Leisch F., Kerschner K., Kypta A., Steinwender C., Kratochwill H., Lukas T., Hofmann R. Long term follow-up in patients with lost coronary stents during interventional procedures. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:367-369.