CHAPTER 54

Femoral Neuropathy

Earl J. Craig, MD; Daniel M. Clinchot, MD

Definition

Femoral neuropathy is the focal injury of the femoral nerve causing various combinations of pain, weakness, and sensory loss in the anterior thigh. The exact incidence of femoral neuropathy is not clear. However, the most common etiology is iatrogenic followed by tumor-related injury [1]. Hemorrhage, most often due to anticoagulation therapy, also is common. Table 54.1 lists other possible causes of femoral neuropathy.

Table 54.1

Possible Causes of Focal Femoral Neuropathy [1,2]

Open Injuries

Retraction during abdominal-pelvic surgery [3,4]

Hip surgery—heat used by methyl methacrylate, especially in association with leg lengthening [5,6]

Penetration trauma (e.g., gunshot and knife wounds, glass shards)

Closed Injuries

Retroperitoneal bleeding after femoral vein or artery puncture [7]

Cardiac angiography

Central line placement

Retroperitoneal fibrosis

Injury during femoral nerve block

Diabetic amyotrophy

Infection

Cancer [8]

Pregnancy

Radiation

Acute stretch injury due to a fall or other trauma

Hemorrhage after a fall or other trauma

Spontaneous hemorrhage—typically due to anticoagulant therapy

Idiopathic

Hypertrophic mononeuropathy [9]

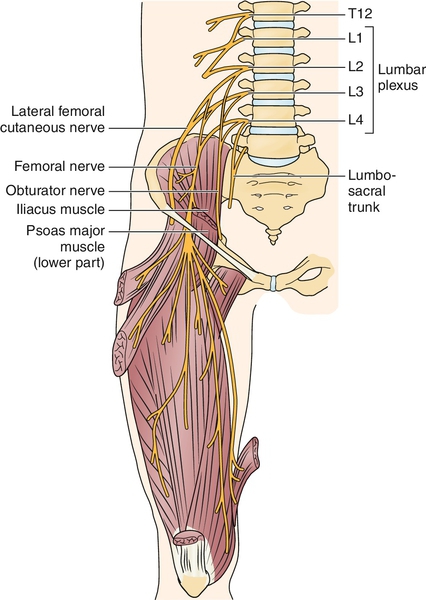

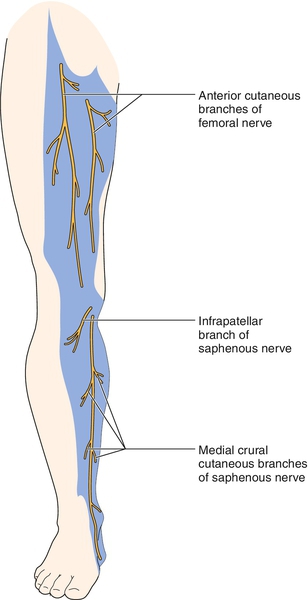

The femoral nerve arises from the anterior rami of the lumbar nerve roots 2, 3, and 4. After forming, the nerve passes on the anterolateral border of the psoas muscle, between the psoas and iliacus muscles, down the posterior abdominal wall, and through the posterior pelvis until it emerges under the inguinal ligament lateral to the femoral artery (Fig. 54.1) [2–4]. The course continues down the anterior thigh, innervating the anterior thigh muscles. The sensory-only saphenous nerve branches off the femoral nerve distal to the inguinal ligament and courses through the thigh until the Hunter (subsartorial) canal, where the nerve dives deep. The femoral nerve innervates the psoas and iliacus muscles in the pelvis and the sartorius, pectineus, rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, and vastus intermedius muscles in the anterior thigh. The femoral nerve provides sensory innervation to the anterior thigh. The saphenous nerve provides sensory innervation to the anterior patella, anteromedial leg, and medial foot (Fig. 54.2).

Symptoms

The symptoms depend on how acute the injury is and what caused the injury. A patient will often first complain of a dull, aching pain in the inguinal region, which may intensify within hours. Shortly thereafter, the patient may note difficulty with ambulation secondary to leg weakness. The patient may or may not complain of weakness in the hip or thigh but will often notice difficulty with functional activities, such as getting out of a chair and traversing stairs or inclines. Numbness over the anterior thigh and medial leg is common. The numbness may extend into the anteromedial leg and the medial aspect of the foot.

Physical Examination

The examination includes a complete neuromuscular evaluation of the low back, hips, and both lower limbs. This should include inspection for asymmetry or atrophy, manual muscle testing, muscle stretch reflexes, and sensory testing for light touch and pinprick.

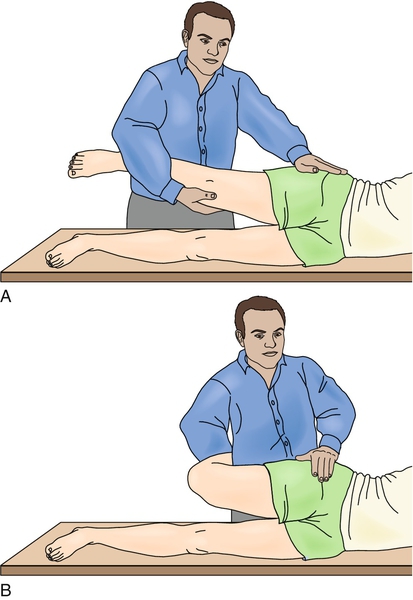

In the case of femoral neuropathy, the clinician may see atrophy or asymmetry of the quadriceps muscles. Weakness of hip flexion or knee extension may be present. Strength testing may be limited because of pain. Quadriceps strength should be compared with adductor strength, which typically is normal. Palpation over the inguinal ligament may reveal a fullness or exacerbate the patient’s pain symptoms. There is often a decreased or loss of quadriceps reflex and decreased sensation to the anterior thigh and anterior and medial leg. The thigh and groin may be tender to palpation. Pain may be exacerbated with hip extension (Fig. 54.3) [2,3].

Functional Limitations

Functional limitations due to femoral neuropathy are generally a result of weakness and vary according to the severity of the injury and the functional reserve of the patient. Individuals may have difficulty in getting up from a seated position and walking without falling. Inclines and stairs often magnify the limitations. Recreational and work-related activities are often affected, such as running, climbing, and jumping.

Diagnostic Studies

Electrodiagnostic studies (nerve conduction studies and electromyography) are the “gold standard” to confirm the presence of a femoral nerve injury. These should be performed no earlier than 3 to 4 weeks after the injury. Obviously, in cases of suspected hemorrhage, imaging studies should be done immediately. Imaging studies may include magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography of the pelvis to look for a hemorrhage or a mass causing impingement [4–7]. Ultrasound has been found to be a valuable tool in needle localization for femoral nerve blocks as well as in the identification of femoral nerve injury [8,9].

In terms of electrodiagnostic studies, nerve conduction studies of the femoral motor component are routinely used. Sensory conduction studies of the medial femoral cutaneous nerve can be useful in the localization of femoral neuropathy [10]. Saphenous nerve sensory evaluation is available but is often technically difficult and unreliable [3]. The needle electromyography should evaluate muscles innervated by the femoral, obturator, tibial, and peroneal nerves. The needle evaluation therefore should include evaluation of the iliopsoas, at least two of the four quadriceps femoris muscles, one or two adductor muscles, gluteus minimus, three muscles between the knee and the ankle, and paraspinal muscles. Electromyography should be performed to rule out other causes of neuropathic thigh pain, including upper and mid lumbar radiculopathy, polyradiculopathy, and plexopathy. Serial electromyographic studies may help with evaluation of the recovery process. High-resolution magnetic resonance neurography is useful in the evaluation of femoral neuropathy, providing insight into pathologic causes including compressive lesions, as can be found in retroperitoneal hemorrhage or cancer [11].

Treatment

Initial

Treatment of femoral neuropathy is focused on three separate areas: relief of symptoms, facilitation of nerve healing, and restoration of function. In acute cases in which hemorrhage or trauma is the cause, surgical intervention may be the initial treatment. This is also the case when the injury is due to a mass lesion, such as a tumor.

Acute, subacute, and chronic relief of the pain and numbness is attempted with modalities and medications. Ice may be helpful acutely, and heat may be helpful in the subacute stage. If an inflammatory component is suspected, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may help both pain and inflammation. Alternatively, oral corticosteroids may be used. Narcotics are used when acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs do not control the pain. Antiseizure medications, such as carbamazepine and gabapentin, are also of benefit for the neuropathic pain in some individuals [12,13]. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation may also help with pain control.

Facilitation of healing depends on the cause of the injury to the nerve. In the case of diabetes, improved blood glucose control may help recovery [14]. Injury due to impingement may be improved by removal of the mass. Too often, little can be done to facilitate healing. Nerves that have sustained a less severe injury (neurapraxia injury) often heal within hours to weeks once the irritant is removed. Nerves that have sustained a more serious injury (neurotmesis or axonotmesis) typically have a much longer healing course because of the time required for wallerian degeneration and regeneration. It is important to educate the patient about the potential for a prolonged (sometimes more than 1 year) course of healing. Also, it is important to counsel patients that healing may not be complete and that there may be permanent loss of strength and sensation as well as continued pain symptoms.

Rehabilitation

Once the damage has been stopped or reversed, the focus turns to improvement of hip flexion and knee extension strength by maximizing the function of the available neuromuscular components. This is accomplished with physical therapy instruction and a home exercise program. Improvement of strength in all lower extremity muscle groups is important. Aggressive strengthening should be limited in a nerve that is acutely injured because it may promote further injury and delay healing [15].

It is also essential to work on proper gait mechanics. The physical therapist can help the patient with gait training and gait aids to prevent falls and to improve energy use. Range of motion in all lower extremity joints should be addressed. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation may be of benefit in improving strength in some individuals.

Procedures

Procedures are not indicated for this disease process.

Surgery

In the case of femoral nerve injury due to impingement, mass lesion, or hemorrhage, surgery may be required to remove the pressure. Early surgical evacuation in patients with femoral nerve compression secondary to retroperitoneal hemorrhage can reduce the likelihood of prolonged neurologic impairment [16]. In the case of a penetrating injury to the femoral nerve, surgery to align the two ends of the nerve and to remove scar tissue may be required. Successful transfer of the obturator nerve to the femoral nerve has also been reported in cases in which the lesion of the femoral nerve is complete [17].

Potential Disease Complications

Potential complications include continued pain, numbness, and weakness despite treatment. In addition, the weakness in the hip and knee increases the risk for falls.

Potential Treatment Complications

Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have well-known side effects that most commonly affect the gastric, hepatic, and renal systems. Narcotics have the potential for addiction and sedation. Carbamazepine can cause sedation and aplastic anemia. The patient taking carbamazepine should be evaluated with serial complete blood counts and checking of carbamazepine level. Gabapentin can cause sedation. The potential risks of surgical intervention include bleeding, infection, and adverse reaction to the anesthetic agent.