CASE 52 Percutaneous Repair of Atrial Septal Defect

Case presentation

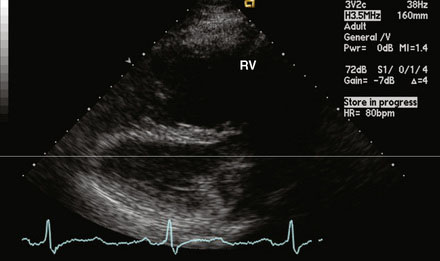

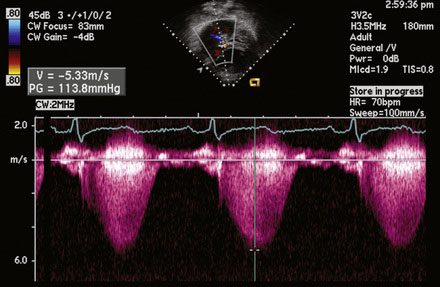

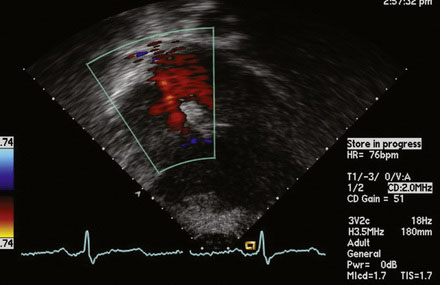

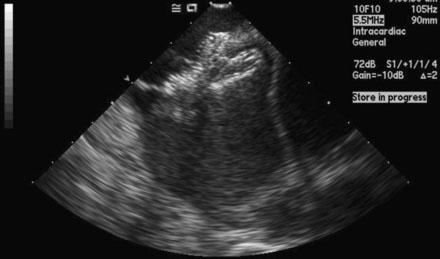

A 12-lead surface electrocardiogram demonstrated sinus rhythm with right axis deviation and a narrow RSR’ in V1, consistent with right ventricular enlargement. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated a markedly dilated right ventricle (Figure 52-1 and Video 52-1) and a tricuspid regurgitant Doppler signal consistent with severe pulmonary hypertension (Figure 52-2). Subcostal imaging demonstrated an atrial septal defect with significant left-to-right shunt across the atrial septum (Figure 52-3 and Video 52-2). There was normal left ventricular size and systolic function. She was referred for percutaneous closure of the atrial septal defect.

Cardiac catheterization

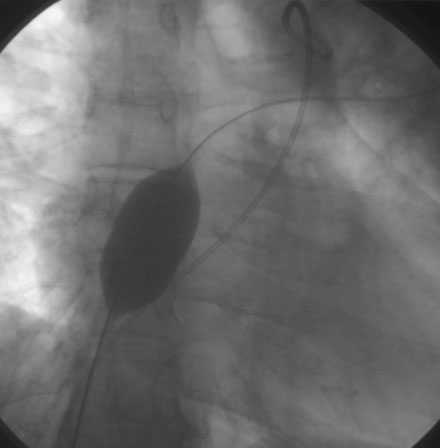

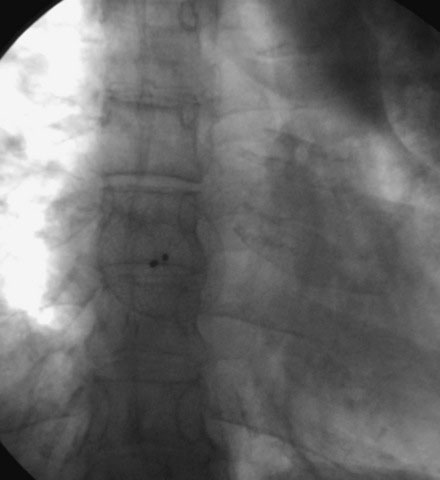

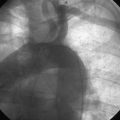

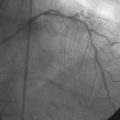

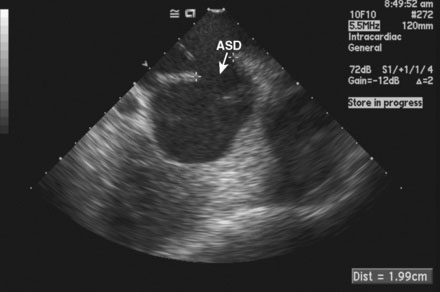

The procedure was performed using conscious sedation. Vascular access initially consisted of a 6 French sheath in the right femoral artery and both 8 and 11 French sheaths in the right femoral vein. The patient received 4000 U of unfractionated heparin intravenously along with 1 g of cefazolin. A 10.5 French intracardiac echocardiography catheter was then inserted through the 11 French sheath and advanced to the right atrium, allowing imaging and sizing of the atrial septal defect as well as confirming normal pulmonary venous return to the left atrium (Figure 52-4 and Video 52-3). A right and retrograde left-heart catheterization was performed for measurement of hemodynamics and shunt calculation. The pulmonary artery pressure was 95/27 mmHg with a mean of 50 mmHg, and oximetry determined a pulmonary to systemic flow ratio (or Qp:Qs) of 1.5:1 on room air. Pulmonary vascular resistance calculated to 9 Wood units. Repeating the hemodynamic measurements on inhaled epoprostenol at 50 ng/kg/min reduced the pulmonary pressure to 70/25 mmHg with a mean of 38 mmHg, with stable systemic pressures and a Qp:Qs ratio of 2.5:1. With pulmonary vasodilator administration, her pulmonary vascular resistance calculated to 3 Wood units-indexed. Selective coronary angiography demonstrated normal coronaries. The decision was made to occlude her atrial septal defect and maintain her on pulmonary vasodilator therapy.

FIGURE 52-4 This is an intracardiac echocardiogram showing the atrial septal defect (measuring 1.99 cm) (arrow).

The atrial septal defect was first sized with a 34 mm sizing balloon, and the stretch diameter was 24 mm (Figure 52-5). A 24 mm Amplatzer septal occluder was then delivered and its position confirmed satisfactorily by intracardiac echocardiography (Figures 52-6, 52-7 and Video 52-4). Repeat hemodynamics confirmed stable pulmonary and wedge pressures. The patient was then monitored in the intensive care unit before being discharged 24 hours later on oral bosentan and sildenafil therapy.

Discussion

A significant atrial septal defect creates a left-to-right shunt due to the higher compliance of the right ventricle and lower right atrial pressures, with a resultant volume overload of the right heart and pulmonary circulation. The natural history of significant atrial septal defects results in a reduced life expectancy (approximately 57% mortality by age 40) and severe pulmonary hypertension in 22%.1,2 Previously, correction of such atrial septal defects required a surgical approach with cardiopulmonary bypass. In attempting surgery in patients with elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (≥7 U/m2), significant mortality and morbidity may result, and extremely elevated resistance (≤15 U/m2) has been associated with death.3

Frequently, percutaneous closure of atrial septal defects is performed with transesophageal guidance under general anesthesia. However, it has been shown that the effects of general anesthesia can raise the mixed venous oxygen saturation and therefore mask the severity of the shunt.4

1 Campbell M. Natural history of atrial septal defect. Br Heart J. 1970;32(6):820-826.

2 Craig R.J., Selzer A. Natural history and prognosis of atrial septal defect. Circulation. 1968;27(4):805-815.

3 Steele P.M., Fuster V., Cohen M., Ritter D.G., McGoon D.C. Isolated atrial septal defect with pulmonary vascular obstructive disease—long-term follow-up and prediction of outcome after surgical correction. Circulation. 1987;76(5):1037-1042.

4 Colonna-Romano P., Horrow J.C. Dissociation of mixed venous oxygen saturation and cardiac index during opioid induction. J Clin Anesth. 1994;6:95-98.